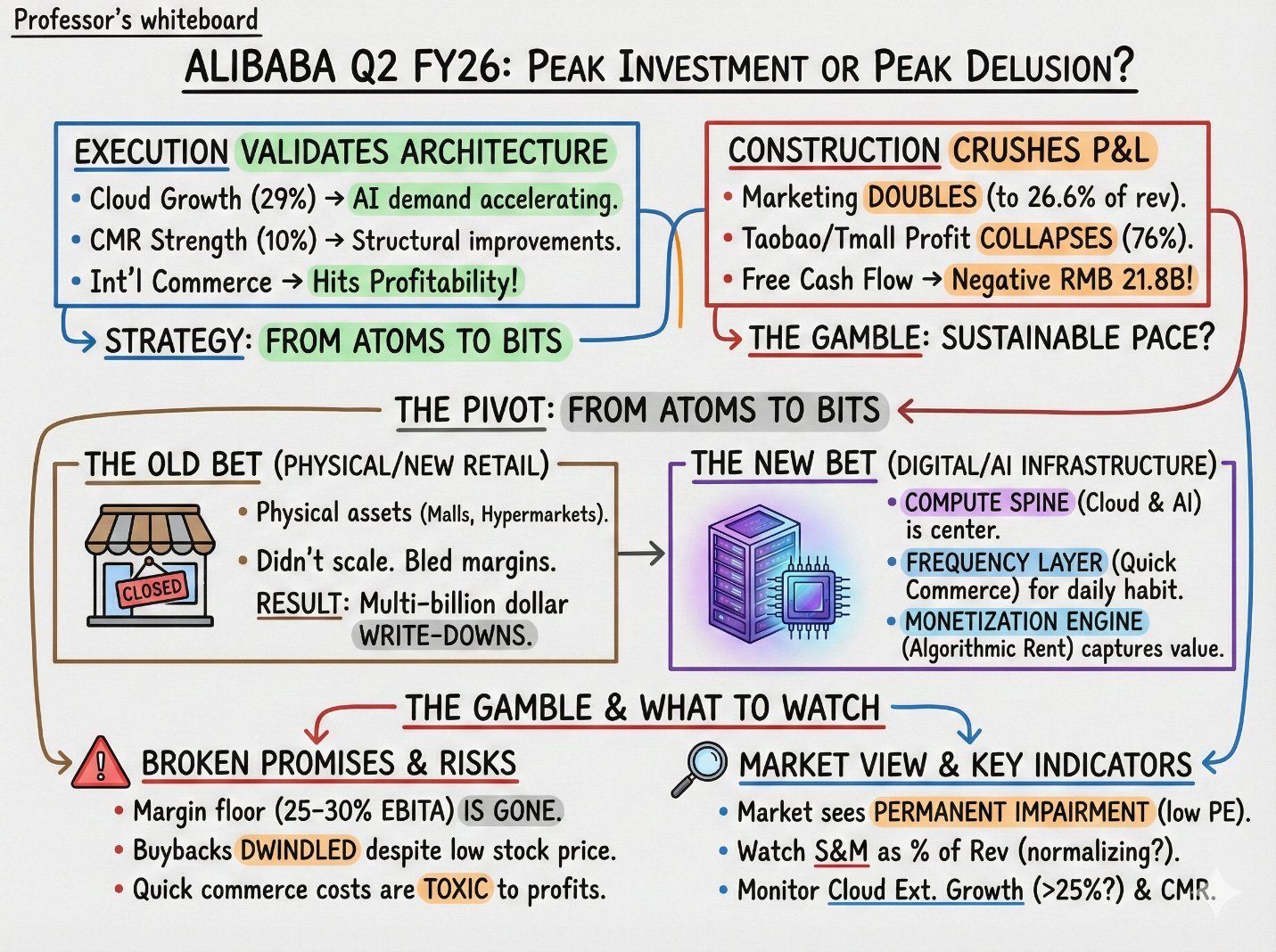

Alibaba Q2 FY26: Peak Investment or Peak Delusion?

A quarter that proves the strategy works—and that the balance sheet can’t absorb many more quarters like it.

TL;DR:

Execution validates the architecture: Cloud growth (29%), CMR strength (10%), and international profitability show the system firing.

But construction crushes the P&L: Marketing doubles, segment profit craters, and free cash flow swings deeply negative.

Everything now hinges on pace: If spending normalizes, the pivot compounds; if not, AI is just New Retail with better branding.

The Bet That Didn’t Work

In October 2016, Jack Ma stood at an Alibaba Cloud conference and made a ten-year forecast that cost his shareholders roughly $3 billion: “In ten to twenty years,” he declared, “there will be no e-commerce, only New Retail.”

The thesis was seductive. Online and offline would merge into a single, frictionless canvas. Physical stores would become data nodes in a digital empire, feeding customer insights back into a central algorithmic brain. The hypermarket around the corner would double as a fulfillment center; the department store downtown would become a showroom with invisible inventory pipes.

What happened next was classic empire-building: a $2.6 billion swallowing of Intime in 2017, a $3.6 billion gulp of Sun Art in 2020, a $4.6 billion bet on Suning back in 2015. Alibaba was buying the physical world to digitize it.

But physical assets have a nasty habit: they don’t scale like software. Hypermarkets bled margin against the relentless price comparison of pure e-commerce. Department stores discovered that discovery had moved to phones, not floors. The promised “data flywheel”—real-world shopping behavior sharpening digital recommendations—spun too slowly to justify the capital locked in concrete and inventory. While Alibaba was renovating malls, Pinduoduo built a $150 billion business by ignoring atoms entirely. Pure software beat software-meets-real-estate.

The unwind arrived in two acts. December 2024: Alibaba announced it would sell Intime for ~$1 billion, crystallizing a $1.3 billion loss. January 2025: Sun Art followed, sold to DCP Capital for an expected $1.8 billion loss. New Retail, the strategy that defined Alibaba’s last decade, had officially returned more value to the scrapyard than to shareholders.

The day of reckoning came in February 2025. On the Q3 FY25 call, CEO Eddie Wu announced where the evacuated capital would flow: over the next three years, Alibaba would invest more in cloud and AI infrastructure than it had in the entire previous decade. The money that built hypermarkets would now build data centers.

The question isn’t whether the pivot was necessary. It’s whether the new bet is structurally smarter—or just a more sophisticated way to burn capital. Q2 FY26, the September 2025 quarter, offers the first real answer.

From Shelves to Circuits

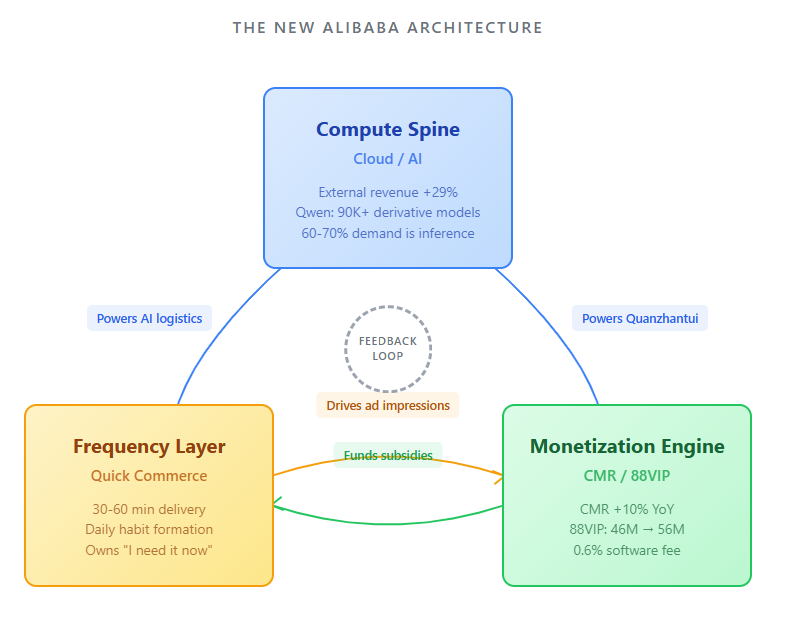

To understand what Alibaba is building instead of department stores, you need to see three systems orbiting each other.

The first is the Compute Spine. This is the new center of gravity. Alibaba Cloud’s external revenue growth: 7% in Q2 FY25, accelerating to 29% in Q2 FY26. AI-related products have posted triple-digit growth for nine consecutive quarters. Qwen, the open-source model family, is now the most-forked LLM on Earth, spawning over 90,000 derivative models.

Here’s why that matters: in December 2024, Wu noted that 60-70% of new demand is inference, not training. Training is a one-time capex splurge. Inference is recurring revenue that scales with usage—every API call, every token generated, every customer query answered by a Qwen-powered bot. Alibaba isn’t just renting servers anymore. It’s renting out the operational nervous system of the AI economy. Instead of owning shelf space, it wants to own the silicon substrate other people’s applications run on.

The second is the Frequency Layer. Quick commerce—30-to-60-minute delivery—looks like a grocery play. It’s not. It’s a bet on daily habit formation.

Meituan owns the intent “I’m hungry.” That’s a high-frequency, high-certainty purchase trigger. Alibaba needs to own the adjacent intent: “I need this now.” Groceries, yes, but also the phone charger you forgot, the pharmacy run, the emergency snack. Every urgent purchase is a reason to open Taobao instead of Meituan. More opens mean more searches, more ad impressions, more chances to cross-sell premium memberships. Frequency Layer businesses are expensive to build—riders, dark stores, subsidies—but they’re defensive moats against someone else hijacking your user’s daily rhythm.

The third is the Monetization Engine. Customer Management Revenue (CMR)—Alibaba’s ad and commission take—grew 2% YoY in Q2 FY25. In Q2 FY26, it grew 10%. That’s not a cyclical bounce. It’s structural. Two levers: Quanzhantui, an AI-driven ad-placement engine that lifts ROI for merchants, and a 0.6% software service fee on all GMV implemented in September 2024. Merchants spend more when the returns are algorithmically guaranteed. The software fee is a take-rate increase in developer clothing.

Meanwhile, 88VIP membership grew from 46 million to 56 million in twelve months. These are Alibaba’s whales: high-spending, low-churn, and—critically—less price-sensitive than the users PDD is fistfighting for at the bottom of the market.

Seen together, the shift is stark. Malls became GPU clusters. POS terminals became ad auctions. Hypermarket aisles became delivery riders. Store footfall became app sessions. The question isn’t whether the architecture is elegant. It’s whether the P&L can survive the construction.

The Bill Arrives

Q2 FY26 is the quarter where both the strategic logic and its financial cost became undeniable.

What worked: Like-for-like revenue grew 15%. Cloud external revenue accelerated to 29% (from 7% a year ago). CMR grew 10% (from 2%). International commerce—long a black hole—recorded its first profitable quarter ever, swinging from a RMB 5 billion loss two quarters prior to breakeven.

What it cost: Non-GAAP EPS fell 72%. Free cash flow plunged to negative RMB 21.8 billion, from positive RMB 13.7 billion a year earlier. Sales and marketing expense doubled to 26.6% of revenue (up from 13.5%). Taobao/Tmml segment profit collapsed 76%. And, most tellingly, share buybacks dwindled to just $253 million—down from $4.1 billion a year earlier—even as the stock languished at multi-year lows with $19.1 billion in remaining authorization.

Management called this “peak investment.” The market heard “peak optimism.” The question is which is closer to the truth: strategic discipline, or exhaustion masquerading as choice.

On my framework, Q2 FY26 confirms something important: the three systems function. The Compute Spine is accelerating. The Frequency Layer is defending daily habit. The Monetization Engine is capturing more value per transaction. But it also reveals something painful: building all three systems at once destroys capital at a rate the old Alibaba never imagined.

What Was Confirmed, What Was Broken

Separating signal from noise in Q2 FY26 means splitting what the quarter confirmed from what it shattered.

Confirmed:

The Compute Spine works. Cloud demand is real and supply-constrained. Management explicitly stated that supply, not demand, is the bottleneck on AI compute. When a cloud business is capacity-limited, that’s a good problem—the kind that justifies capex.

Monetization is structural, not promotional. CMR growth held steady even as subsidy wars with PDD and Douyin intensified. The take-rate improvements came from product (Quanzhantui) and policy (software fee), not from temporary dealer incentives.

International commerce can be tamed. The path to profitability that management promised in December 2024 is materializing faster than expected. Lazada and Trendyol are no longer just strategic options; they’re profit contributors.

Broken:

The margin floor is gone. Alibaba once operated at 25-30% EBITA margins. That era is over. The new mix—quick commerce, AI buildout, user acquisition subsidies—is structurally lower-margin. Even perfect execution lands you in the high teens, not the mid-twenties.

The buyback promise is dead. Repurchasing $253 million at multi-year lows while holding $19.1 billion in dry powder isn’t capital discipline. It’s a liquidity warning. Management is telling you, in the clearest possible language, that they need every dollar for defense and construction.

Quick commerce optimism was naive. I previously believed improving unit economics would make the Frequency Layer self-funding. I was wrong. At current subsidy intensity, quick commerce growth is toxic to consolidated profits. It can be strategically correct and financially destructive simultaneously.

Here’s the subtlety that makes Alibaba maddening: the machine works, but the P&L can’t support the construction pace. Q2 FY26 is the first quarter where that tension became mathematically unsustainable.

Where the Market Blinks

At 16-17x forward earnings, Alibaba is priced as a structurally impaired commerce company with a decent-but-not-dominant cloud appendage, permanently exiled to lower margins and a China-risk discount. The market sees permanent damage.

I see something else: the regulatory crisis of 2020-2022 forced a necessary detox. The antitrust crackdown broke the empire-building impulse. Capital could no longer spray indiscriminately at “innovation initiatives.” What emerged is leaner: a Compute Spine serving the AI economy, a Frequency Layer defending daily habit, a Monetization Engine extracting algorithmic rent.

The market is making three mistakes.

Cloud is underpriced. A business growing 30% with an AI revenue mix, in a macro environment that’s muddling-not-collapsing, should not trade like a legacy telco. The “national AI grid” thesis—where Alibaba becomes the default infrastructure for China’s AI adoption—hasn’t even begun to be priced in.

Quick commerce is misread as offense when it’s defense. Yes, it’s expensive. But ceding daily frequency to Meituan would be terminal. Meituan already owns “I’m hungry”; letting it own “I need it now” would let it work upstream into every other category. Sometimes the right move is a costly moat.

“Peak investment” is credible not because management is virtuous, but because the math is ruthless. Another quarter like Q2 FY26 and the balance sheet buckles. Exhaustion, it turns out, is a catalyst for better capital allocation.

The disagreement, in one line: the market sees permanent impairment; I see deliberate P&L destruction for a finite period to build assets that compound.

The Three Paths Forward

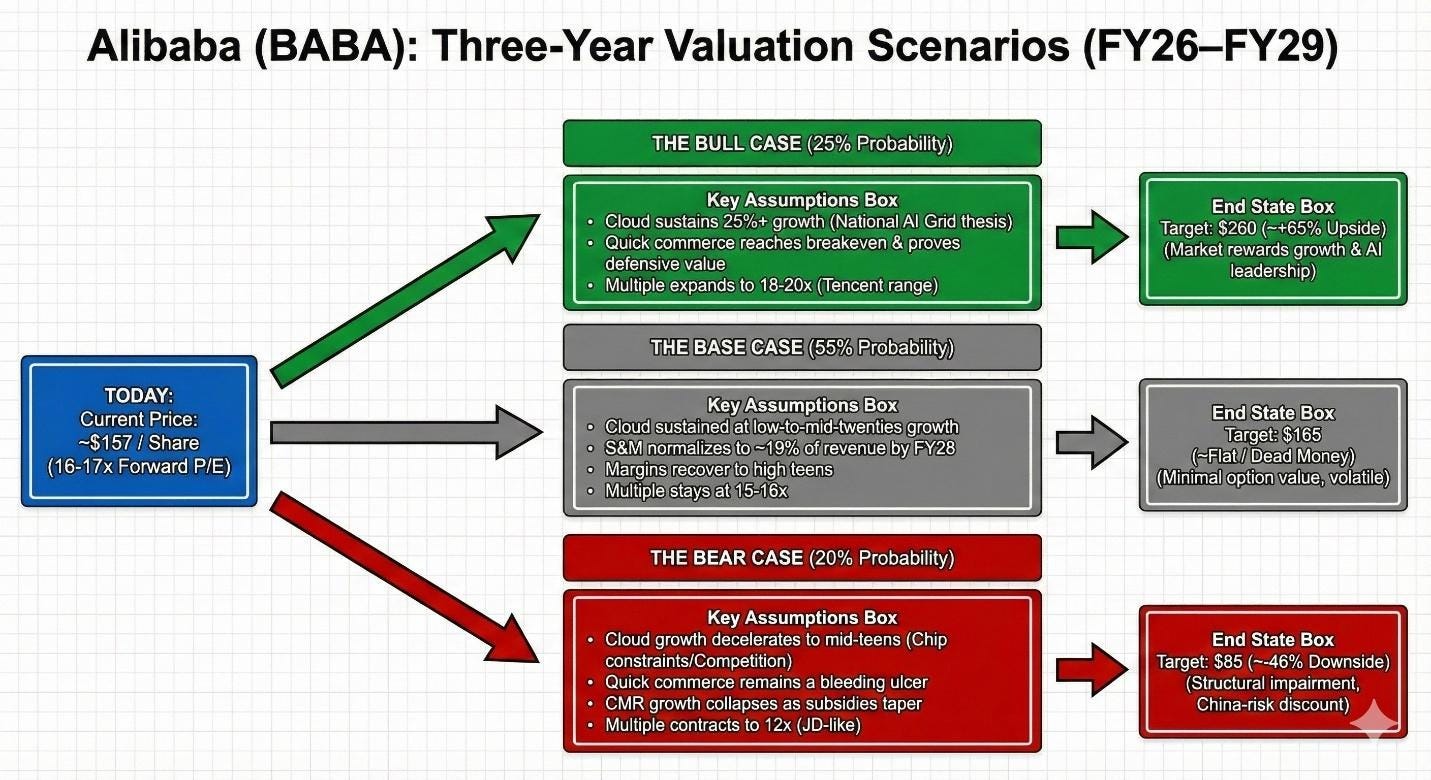

Scenarios are only useful if they force you to name your assumptions. Here are mine.

Bear Case (20% probability): Cloud growth decelerates to mid-teens as chip constraints and Huawei Cloud competition bite. Quick commerce remains a bleeding ulcer. CMR growth collapses when subsidies finally taper. The market applies a JD-like 12x multiple to trough earnings of ~$55. Stock price: $85. From $157, that’s -18% annualized.

Base Case (55% probability): Cloud sustains low-to-mid-twenties growth. Sales and marketing normalizes to ~19% of revenue by FY28 as the Frequency Layer reaches scale. Margins recover to the high teens. Multiple stays at 15-16x. Stock price: $165. Roughly flat from here—dead money with volatility.

Bull Case (25% probability): Cloud re-rates on the “national AI grid” thesis, quick commerce reaches breakeven and proves its defensive value, and the multiple expands toward Tencent’s 18-20x range. Stock price: $260. That’s ~18% annualized.

The crucial insight: at $157, you’re roughly paying for the base case with minimal option value to the bull case. The entire bull case hinges on Cloud sustaining 25%+ growth and the market eventually caring. If you don’t believe both will happen, there’s no reason to own this stock.

The Dashboard

Complexity demands a simple dashboard. Here’s what I’m watching.

Sales & Marketing as % of Revenue. If it drifts toward 19-20% over the next 3-4 quarters, “peak investment” was real. If it stays above 24%, management either lied or lost control of the quick commerce arms race.

Cloud External Growth. Above 25% with stable gross margins = thesis on track. Below 20% while capex remains elevated = building capacity for demand that isn’t coming. That’s a value trap.

CMR Growth vs. S&M Normalization. If CMR holds above 8% while marketing spend falls, monetization improvements are structural. If CMR drops with spend, the growth was subsidized and the thesis cracks.

The Buyback Resurrection. If free cash flow recovers to positive and buybacks stay token, management is telling you capital demands are larger than they appear. That’s a hidden red flag. If buybacks ramp above $2B/quarter once FCF stabilizes, the capital allocation discipline is real.

I exit on: two consecutive quarters of cloud <20% growth with elevated capex, CMR collapsing when S&M tapers, or management language shifting from “peaked” to “sustained investment required.”

The Bottom Line

The last decade’s bet on malls and department stores was expensive and wrong for a simple reason: physical retail doesn’t compound in a world where attention and logistics are both being commoditized. New Retail failed not because the vision was insane—online-offline integration works in instant grocery—but because Alibaba’s specific assets never found structural defensibility against pure-play software competitors.

The current bet—compute and 30-minute habit formation—at least plays on fields where economics improve with scale. Every API call generates marginal revenue. Every delivery builds behavioral lock-in. Every Quanzhantui campaign that delivers ROI captures the next dollar of ad spend. These are businesses with feedback loops.

Q2 FY26 is the bill for switching bets. The architecture looks sound. The cost was brutal. Whether shareholders get repaid depends on something far simpler than AI visions or quick commerce scale: when the next few bills arrive, are they getting smaller?

If yes, the pivot works. If not, Alibaba isn’t a transformation story. It’s just a very expensive way to learn that empire-building is empire-building, whether the bricks are made of concrete or silicon.

Disclaimer:

The content does not constitute any kind of investment or financial advice. Kindly reach out to your advisor for any investment-related advice. Please refer to the tab “Legal | Disclaimer” to read the complete disclaimer.