TL;DR:

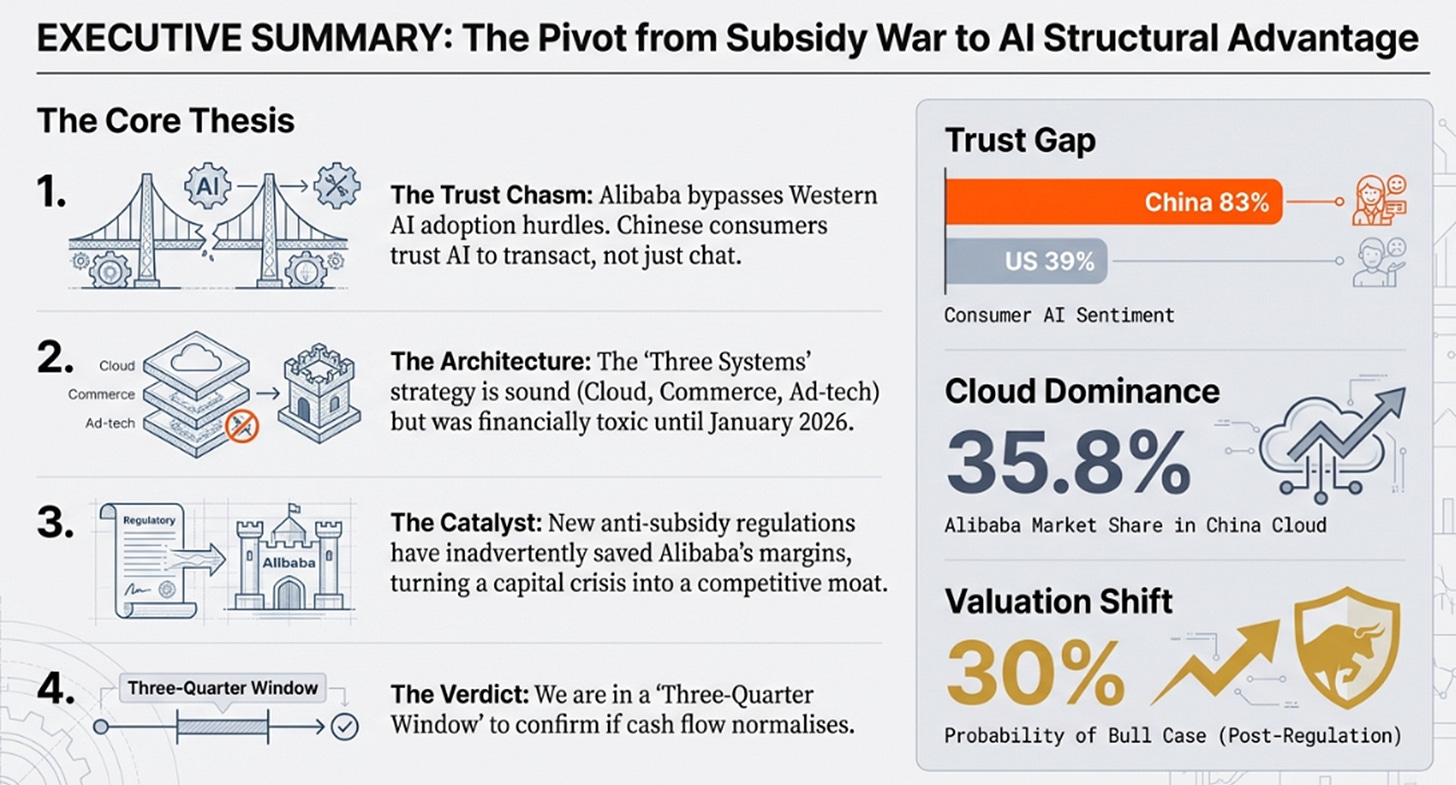

Alibaba’s historical advantage was trust infrastructure. It’s now extending that trust from payments to AI decision-making and transaction execution.

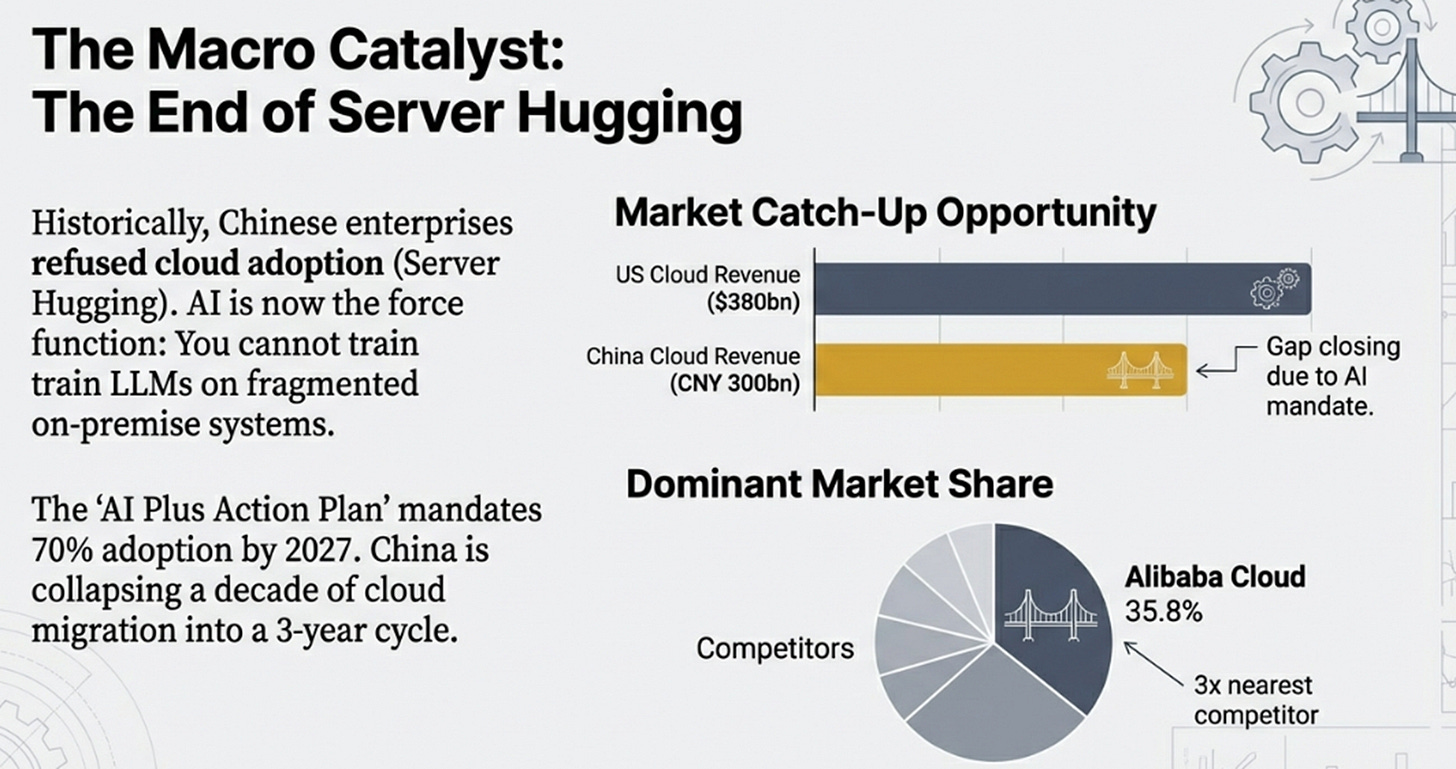

Enterprise AI is forcing China’s delayed cloud adoption to collapse into a catch-up cycle. Alibaba’s cloud share positions it as a primary beneficiary.

The only real question is financial endurance. Q3/Q4 will show whether subsidy costs normalize and whether quick commerce stops bleeding.

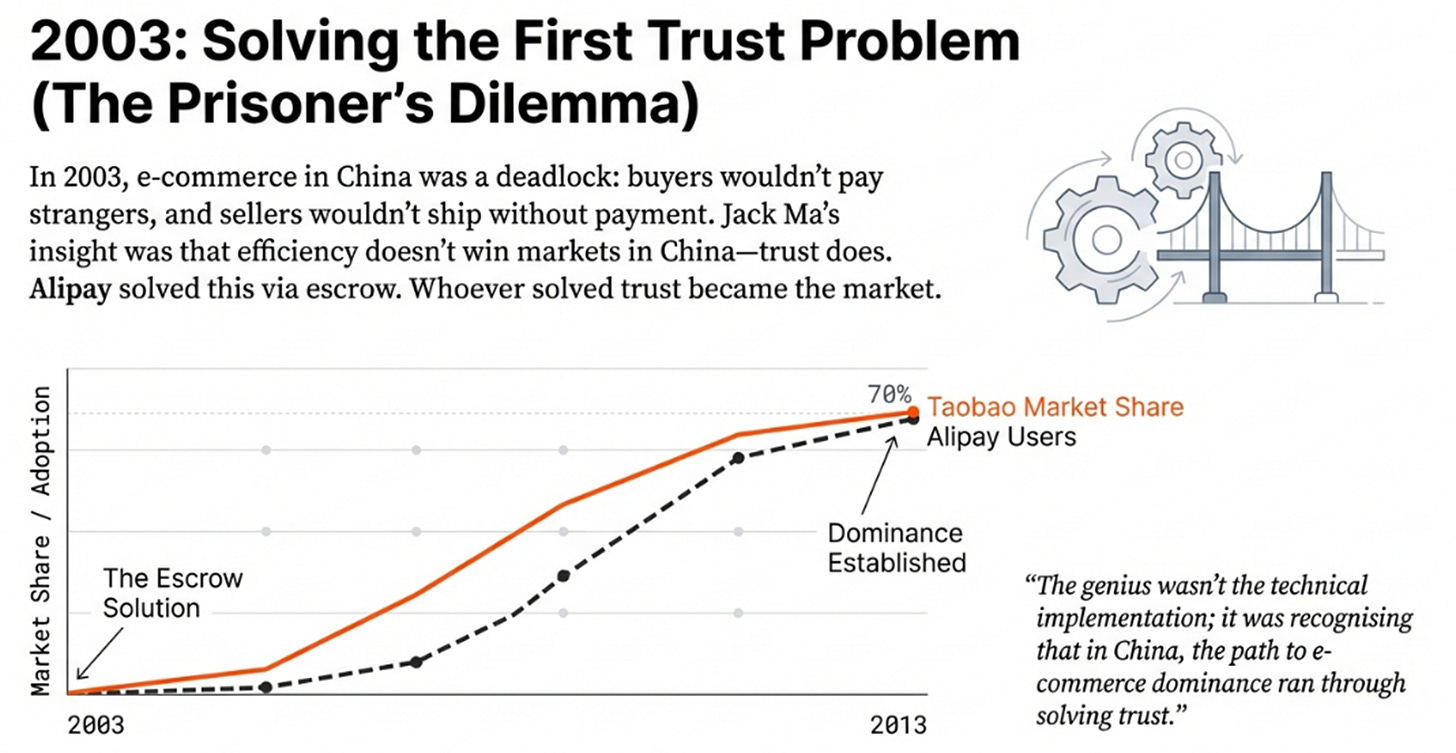

In 2003, Taobao had a problem that had nothing to do with technology. Chinese consumers wouldn’t send money to strangers on the internet. Sellers wouldn’t ship goods before receiving payment. Every transaction was a prisoner’s dilemma.

Jack Ma’s solution wasn’t to build a better marketplace—it was to become the trusted intermediary. Alipay held the buyer’s payment in escrow until delivery was confirmed. The genius wasn’t the technical implementation; it was recognizing that in China, the path to e-commerce dominance ran through solving trust, not efficiency.

By 2013, Taobao had 70% market share. By 2020, Alibaba was processing trillions in GMV. The lesson wasn’t just that trust mattered—it was that whoever solved the trust problem didn’t just win the market; they became the market.

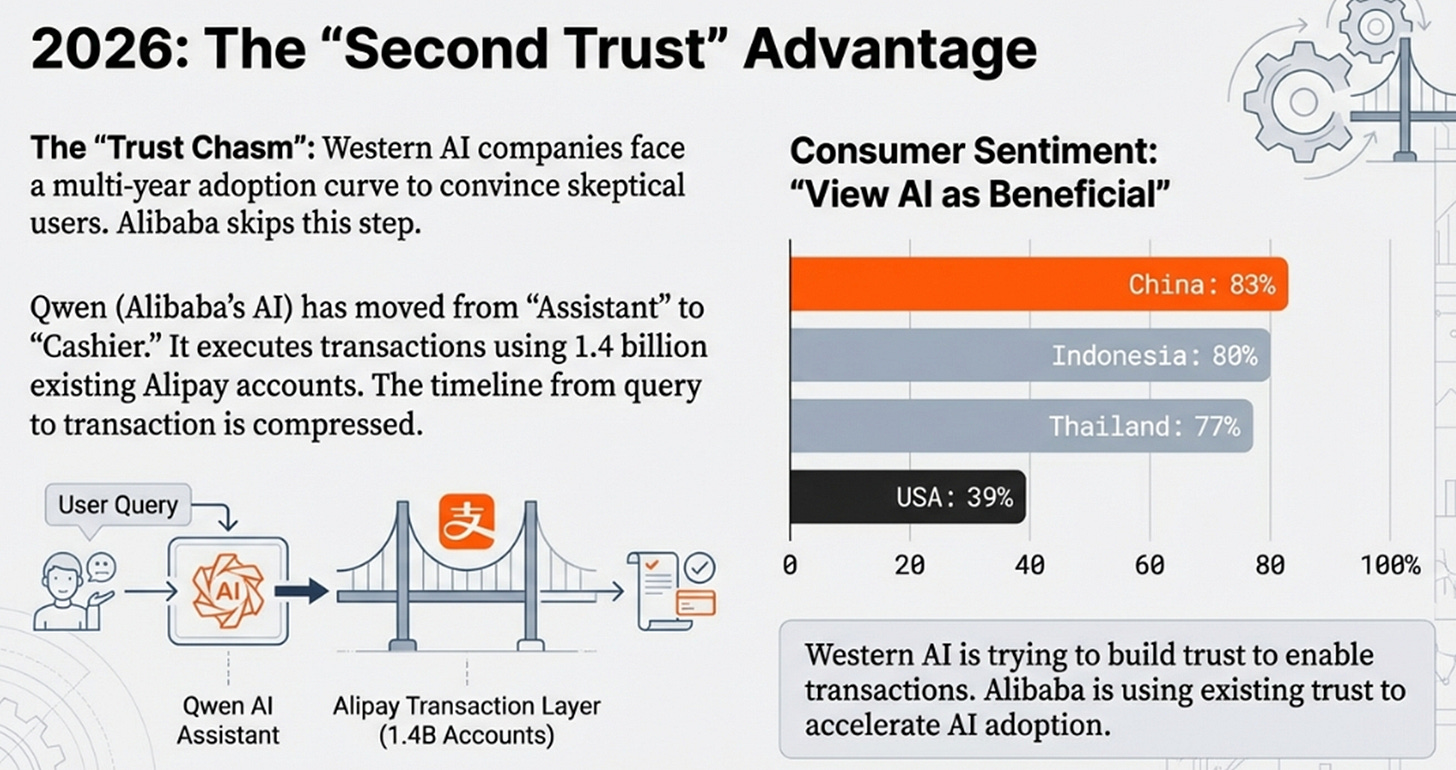

Twenty-three years later, Alibaba faces a different trust problem. Western consumers don’t trust AI to make decisions for them. Chinese consumers do. The gap between those two realities—what researchers call the “Trust Chasm”—might be worth more than the original Alipay bet. But this time, Alibaba isn’t trying to solve the trust problem. They’re trying to exploit it.

The question is whether they can afford to.

What Happened in November

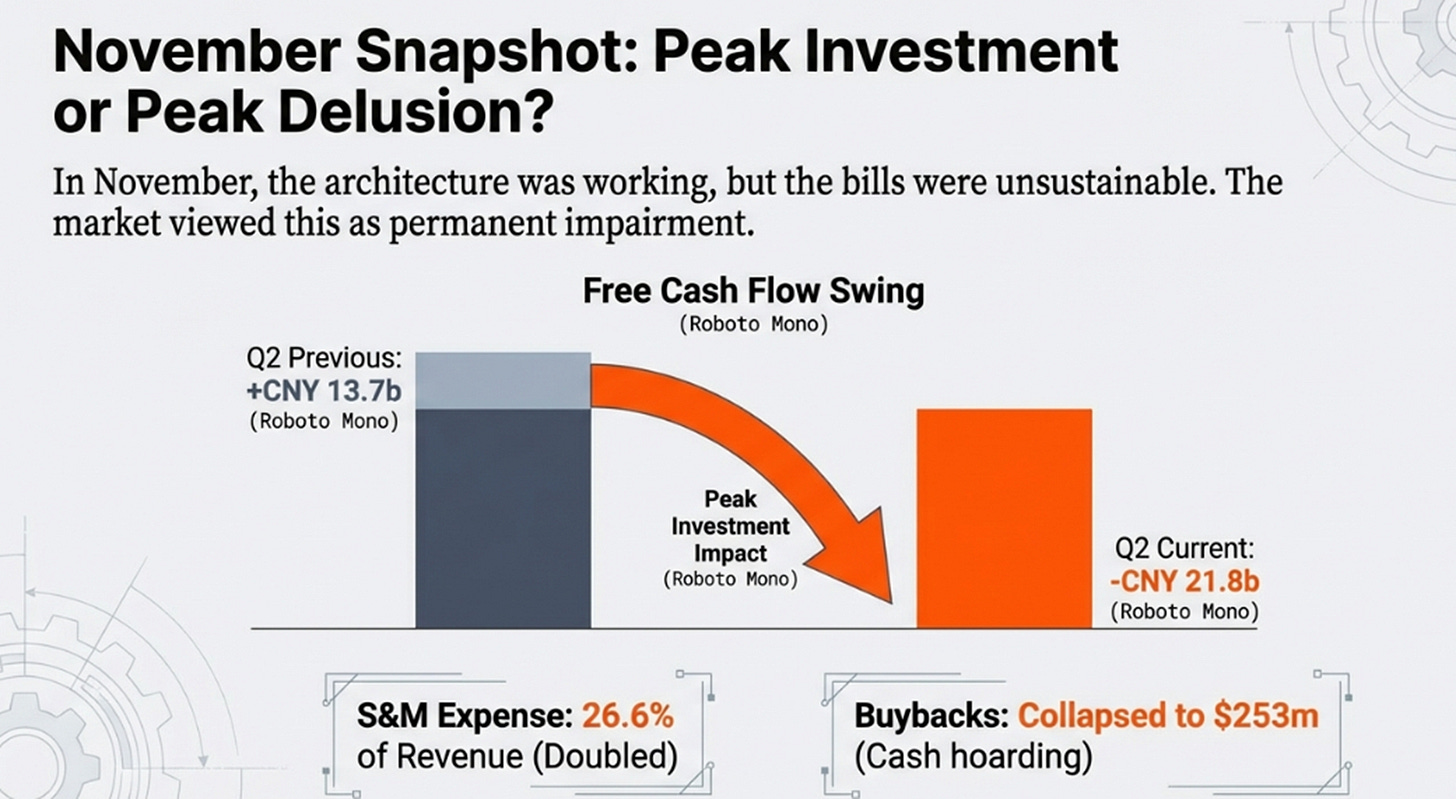

Two months ago, I wrote about Alibaba’s Q2 FY26 results and called it “Peak Investment or Peak Delusion?” The data was brutal: free cash flow swung from positive CNY 13.7 billion to negative CNY 21.8 billion. Sales and marketing expenses doubled to 26.6% of revenue. Buybacks collapsed from $4.1 billion to $253 million even as the stock traded near multi-year lows.

But the quarter also validated something important: the architecture worked. Cloud revenue accelerated to 29% growth. Customer management revenue—Alibaba’s ad and commission business—grew 10% despite intensifying subsidy wars. International commerce posted its first profitable quarter ever.

I wrote then that everything hinged on one question: would the next few bills be smaller?

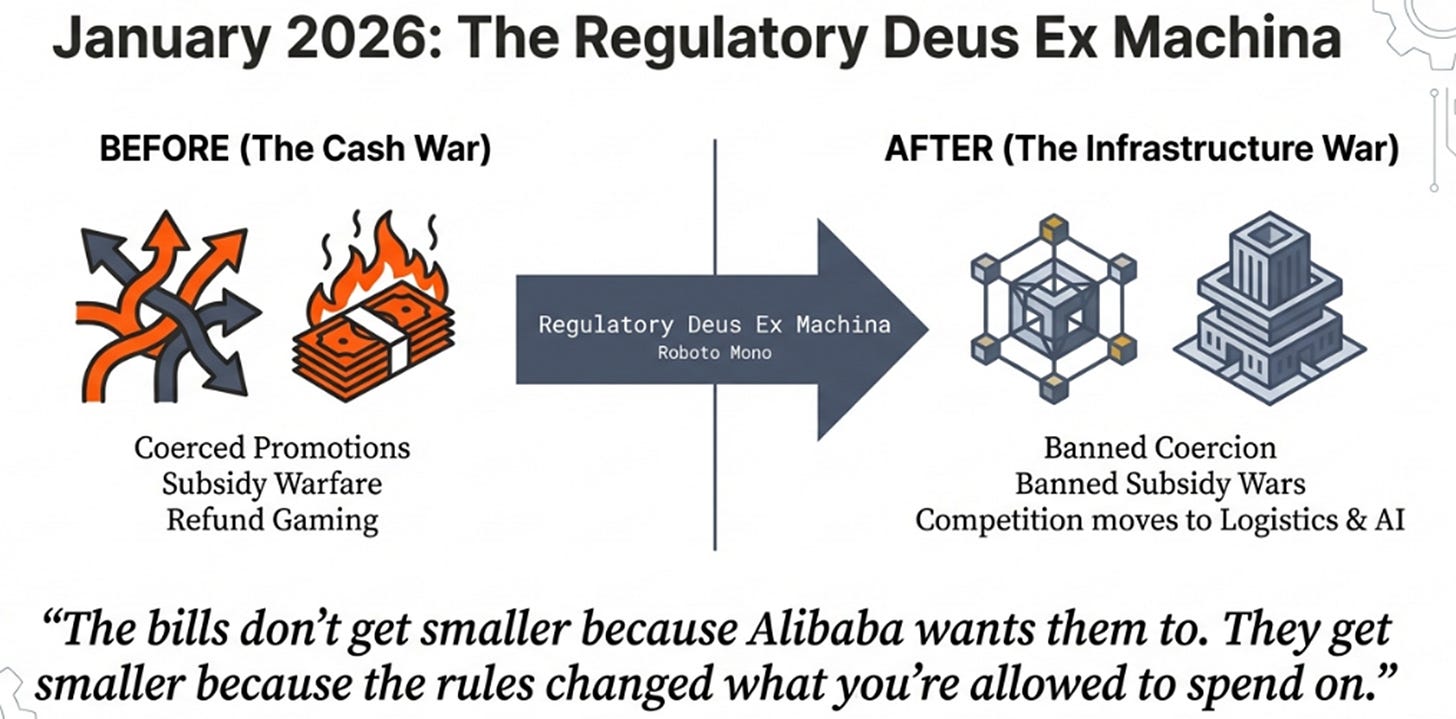

We’re about to find out. Q3 FY26 earnings drop in early February. That quarter includes the first full period after China’s January 2026 e-commerce regulations took effect—regulations that banned the kind of coerced merchant promotions and subsidy warfare that destroyed margins in Q2.

The market thinks those regulations don’t matter. I think they change everything.

The Trust Chasm as Economic Advantage

Start with a data point: 83% of Chinese consumers view AI as more beneficial than harmful. In the United States, that number is 39%. Similar patterns across Asia—Indonesia at 80%, Thailand at 77%, India at 71%.

This isn’t cultural curiosity. It’s structural advantage that changes AI monetization.

When OpenAI wants to monetize ChatGPT, it faces a multi-year adoption curve: build the product, convince skeptical users, overcome privacy concerns, demonstrate value, then charge. The Trust Chasm means every step takes longer in Western markets because the default stance is suspicion.

Alibaba starts differently. They have 930 million Taobao users and 1.4 billion Alipay accounts who’ve trusted them with payment credentials, shipping addresses, purchase histories, and location data for years. When Qwen—Alibaba’s AI model—can execute transactions instead of just suggesting them, it’s not asking users to make a trust leap. It’s offering a better interface for things they already do.

In January 2026, Qwen crossed that threshold. The app moved from answering questions to completing purchases. Users can now order food, book travel, and process payments without leaving the AI interface. This isn’t an AI assistant—it’s an AI cashier with access to the entire Alibaba ecosystem.

The strategic inversion is subtle but crucial. Western AI companies are trying to build enough trust to enable transactions. Alibaba is using existing trust to accelerate AI adoption. The monetization timeline compresses by years.

But there’s a parallel advantage that matters even more for Alibaba’s cloud business: China’s decade-long resistance to cloud computing is collapsing.

Chinese enterprises historically refused cloud adoption. The numbers tell the story—China’s entire cloud market generated roughly CNY 300 billion in revenue versus $380 billion in the US, despite similar GDP. The preference for owning servers, whether driven by cost concerns, data sovereignty fears, or cultural software-buying patterns, meant China’s cloud adoption lagged years behind the West.

AI changes the physics. You cannot train large language models on fragmented on-premise systems. You cannot pirate generative AI at scale. When Beijing’s AI Plus Action Plan mandates 70% AI adoption by 2027 and 90% by 2030, enterprises that skipped a decade of cloud migration suddenly face a compressed catch-up cycle.

Alibaba holds 35.8% of China’s AI cloud market—more than three times its nearest competitor. The question isn’t whether cloud demand will materialize. It’s whether Alibaba can capture it profitably while building two other expensive systems simultaneously.

The Three Systems and Their Cost

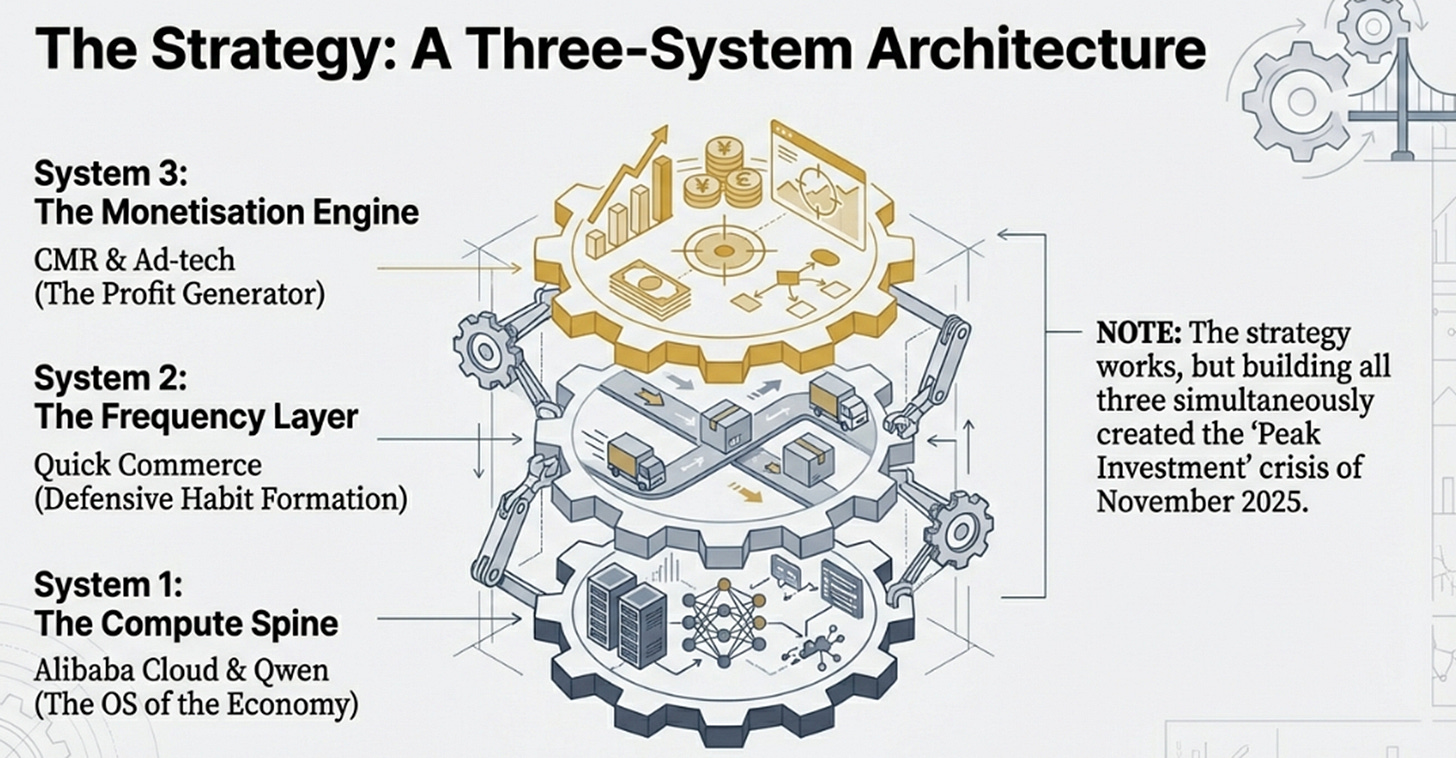

In November, I described what Alibaba was building as three interconnected systems. Two months later, with January’s regulatory changes and February’s earnings approaching, it’s worth revisiting that framework—not because the strategy changed, but because the cost structure might be changing.

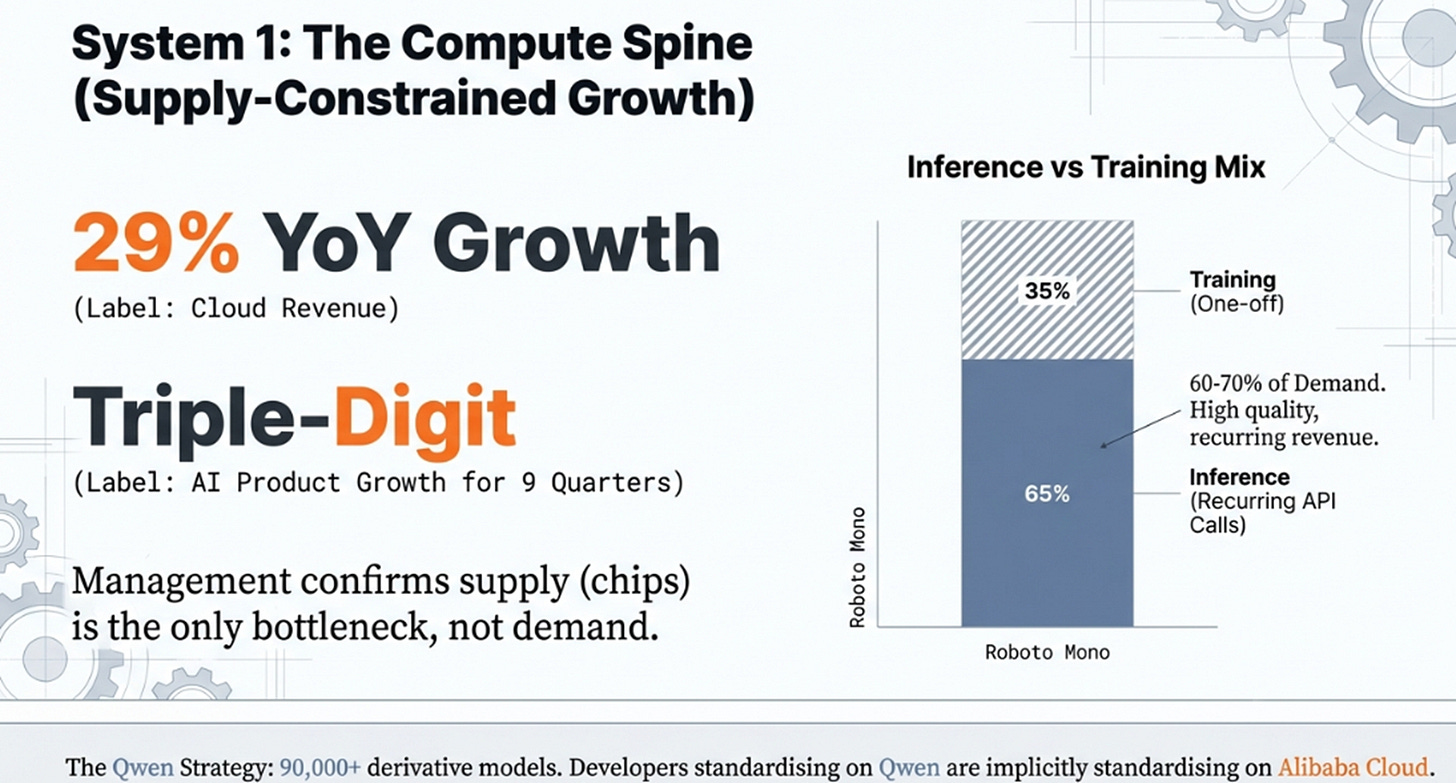

The first system is what I called the Compute Spine. This is Alibaba Cloud, growing at 29% with AI products posting triple-digit growth for nine consecutive quarters. Management said explicitly that supply, not demand, is the bottleneck. When 60-70% of cloud demand is inference rather than training—meaning recurring API calls rather than one-time model builds—you’re renting the operational nervous system of an economy, not just spare server capacity.

Qwen’s open-source strategy makes sense in this context. With over 90,000 derivative models built on Qwen’s foundation, every developer standardizing on Alibaba’s model architecture is implicitly standardizing on Alibaba’s cloud stack. You can fork the model for free; at scale, you need Alibaba Cloud.

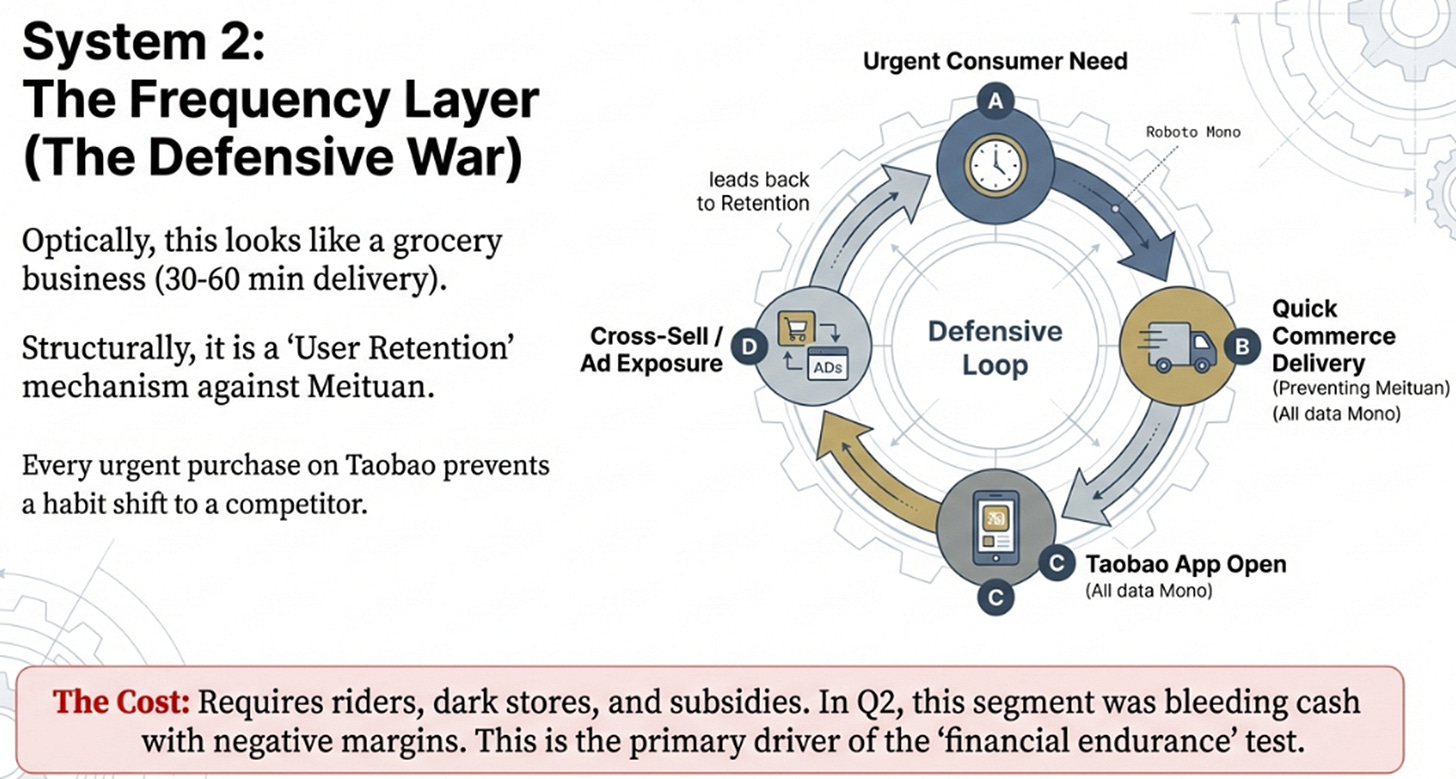

The second system is the Frequency Layer. Quick commerce—30-to-60-minute delivery—looks like a grocery play. It’s actually a defensive bet against Meituan owning the daily habit layer. Every urgent purchase that opens Taobao instead of Meituan is a chance to surface ads, cross-sell memberships, and keep users inside Alibaba’s ecosystem. This is expensive to build—riders, dark stores, subsidies—and in Q2 it was still losing money at a rate that made the entire strategy look questionable.

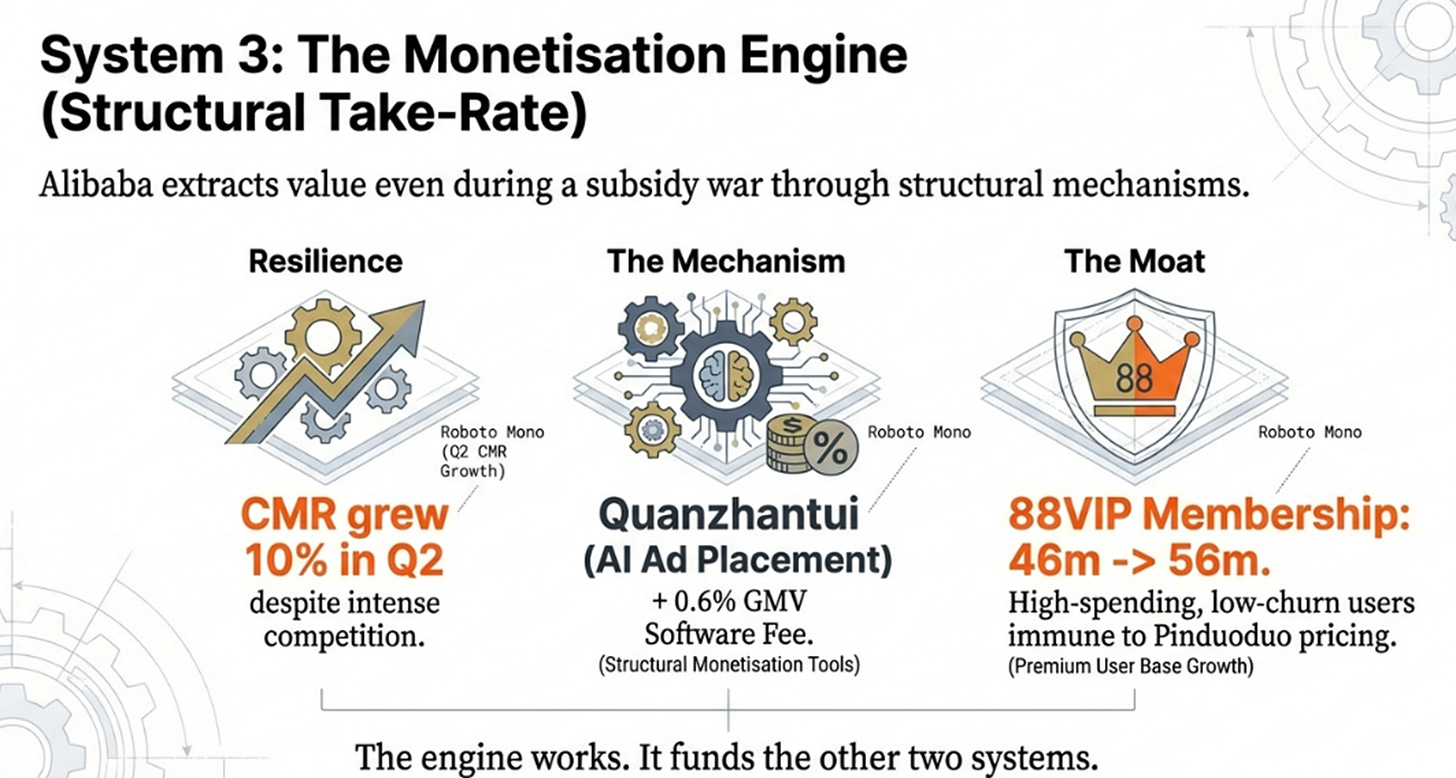

The third system is the Monetization Engine. Customer management revenue—the ad and commission business—grew 10% in Q2 despite intensifying competition. Two specific levers drove that: Quanzhantui, an AI-powered ad placement system that guarantees ROI to merchants, and a 0.6% software service fee on all GMV implemented in September 2024. Meanwhile, 88VIP membership grew from 46 million to 56 million—high-spending, low-churn customers who are less price-sensitive than the users Pinduoduo is competing for.

The problem in November was that building all three systems simultaneously was generating bills that the P&L couldn’t absorb. Sales and marketing at 26.6% of revenue. Negative free cash flow. Token buybacks. Management called it “peak investment.” The market heard “permanent impairment.”

Then came January’s regulatory intervention.

China’s new e-commerce rules banned platforms from coercing merchants into promotions. They prohibited no-questions-asked refund policies that were being gamed. They blocked exclusivity arrangements that pressured small merchants. The regulations didn’t target Alibaba specifically—they targeted the subsidy warfare that was bleeding everyone.

But the impact isn’t neutral. When competition shifts from “who can subsidize more” to “who has better logistics, AI, and service,” years of investment stop being margin-dilutive expenses and start becoming competitive advantages. The bills don’t get smaller because Alibaba wants them to. They get smaller because the rules changed what you’re allowed to spend on.

How My November Analysis Held Up

In November, I laid out three scenarios with explicit probabilities: 20% chance of a bear case reaching $85, 55% chance of a base case around $165, and 25% chance of a bull case hitting $260.

The stock was at $157 then. Today it’s around $165 in USD terms, roughly HK$160 in the Hong Kong listing. We’re tracking the base case, but with a twist—the probabilities themselves have shifted.

Two things I got right: First, that the three systems architecture was sound even if the execution was expensive. Q2 validated that the Compute Spine works with supply-constrained cloud growth, the Monetization Engine functions with CMR growth holding through subsidy wars, and even International Commerce could be tamed with its first profitable quarter. Second, that everything hinged on whether the bills would get smaller. The January regulations directly address that question.

One thing I got wrong: I believed quick commerce unit economics would improve organically through scale. The Q2 data showed I was too optimistic—at the subsidy intensity required to compete with Meituan, growth was toxic to consolidated profits. I wrote: “It can be strategically correct and financially destructive simultaneously.” That’s still true, but the January regulations change the timeline for when the financial destruction ends.

The updated probability distribution reflects that learning: 20% bear remains unchanged because geopolitical and execution risks persist, 50% base is down from 55% because there’s less middle ground than I assumed, and 30% bull is up from 25% because the regulatory de-escalation makes the bull case more achievable.

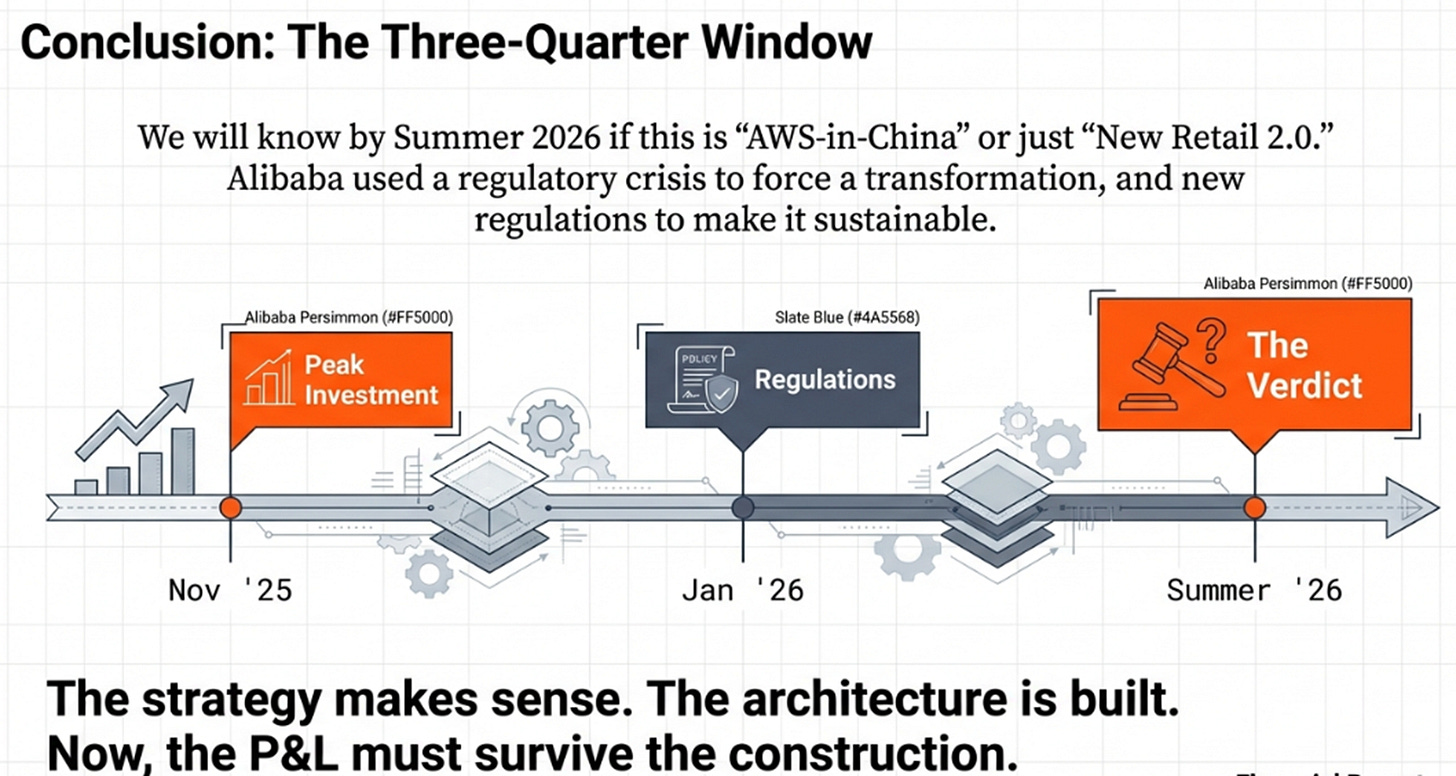

What matters more than the specific numbers is the realization that we’re entering a three-quarter window where the thesis either validates or breaks. Q3 will show whether January’s regulations actually moderated subsidies. Q4 will show whether quick commerce can reach profitability. By the end of calendar 2026, we’ll know if this was AWS-in-China or New Retail 2.0.

Three Ways This Plays Out

Scenarios are useful only if they force you to name what would have to happen. Here are the three paths and what each requires.

The bear case—where the stock trades down to HK$107—requires one of two things: either the strategic bet fails, or geopolitics intervenes. Strategic failure looks like cloud growth decelerating below 20% while capex stays elevated, meaning Alibaba is building capacity for demand that isn’t materializing. It looks like sales and marketing staying above 24% of revenue through 2027 because the January regulations didn’t actually stop the subsidy war—enforcement failed or competitors found loopholes. It looks like customer management revenue collapsing when marketing spend finally tapers, proving the growth was subsidized all along. The market would apply a JD-style 12x multiple to depressed earnings around CNY 148 billion in fiscal 2029. Getting there requires believing that quick commerce never reaches profitability, cloud commoditizes under competition from Huawei and ByteDance, and the AI monetization story was always more narrative than economics. The alternative path is geopolitical: US chip sanctions tighten to the point where Alibaba’s cloud can’t compete, or Treasury forces a delisting. At 20% probability, this isn’t the base case, but it’s not a tail risk either.

The base case—where the stock reaches HK$217—is what I called “successful but unspectacular” in November. Revenue grows at 10% annually through fiscal 2029 as e-commerce stabilizes and cloud sustains 26-28% growth. Margins recover to 15.5% net income—below the 16.2% consensus expects, but respectable given the mix shift toward lower-margin businesses. Quick commerce breaks even sometime in Q4 2026 or Q1 2027, proving it was defense worth paying for but never becoming a profit engine. Sales and marketing normalizes to 19-21% of revenue by late 2027, validating that “peak investment” wasn’t just management narrative. Customer management revenue holds at 8-10% growth even as subsidies moderate, confirming that Quanzhantui and the software service fee created structural take-rate improvements. Free cash flow turns positive in fiscal 2027, enabling buybacks to resume at CNY 10-12 billion per quarter—not aggressive, but enough to signal the capital crisis is over. The stock trades at 16x forward earnings, a modest re-rating from current levels but nothing dramatic. This outcome requires believing the January regulations work as intended, that cloud demand is real but faces pricing pressure, and that Qwen drives incremental GMV without transforming shopping behavior. At 50% probability, this is where I’m anchored—the thesis works, but doesn’t dazzle.

The bull case—HK$323—requires the Trust Arbitrage thesis to materialize fully. Cloud growth sustains at 30%+ through 2028 as the forced migration from on-premise to cloud accelerates under government mandates. More importantly, margins expand simultaneously—reaching 17-18% operating margin in cloud as Alibaba’s Aegaeon software optimizations and supply constraints give them pricing power against weaker competitors. Quick commerce reaches profitability by Q2-Q3 2026 and scales to 5-6% margins by 2028, proving the Frequency Layer is both defensible moat and accretive business. Customer management revenue grows 12-15% annually as AI-powered ad targeting through Quanzhantui proves so effective that merchants increase spend even as subsidies fall. Qwen engagement metrics hit 40%+ daily-to-monthly active user ratios with measurable transaction frequency increases. Sales and marketing normalizes faster than base case—reaching 18-19% by mid-2027—because regulatory de-escalation is more complete than expected. The combination triggers a multiple re-rating to 20x as the market recognizes Alibaba as essential computing backbone, not just a Chinese e-commerce company with a cloud appendage. Aggressive buybacks—CNY 15-20 billion per quarter—accelerate the earnings per share improvement. There’s even a 25% chance Ant Group finally IPOs, crystallizing CNY 50-60 billion in present value. This requires everything going right: execution, regulation, geopolitics. At 30% probability, it’s achievable but not assured.

What To Watch When Q3 Reports

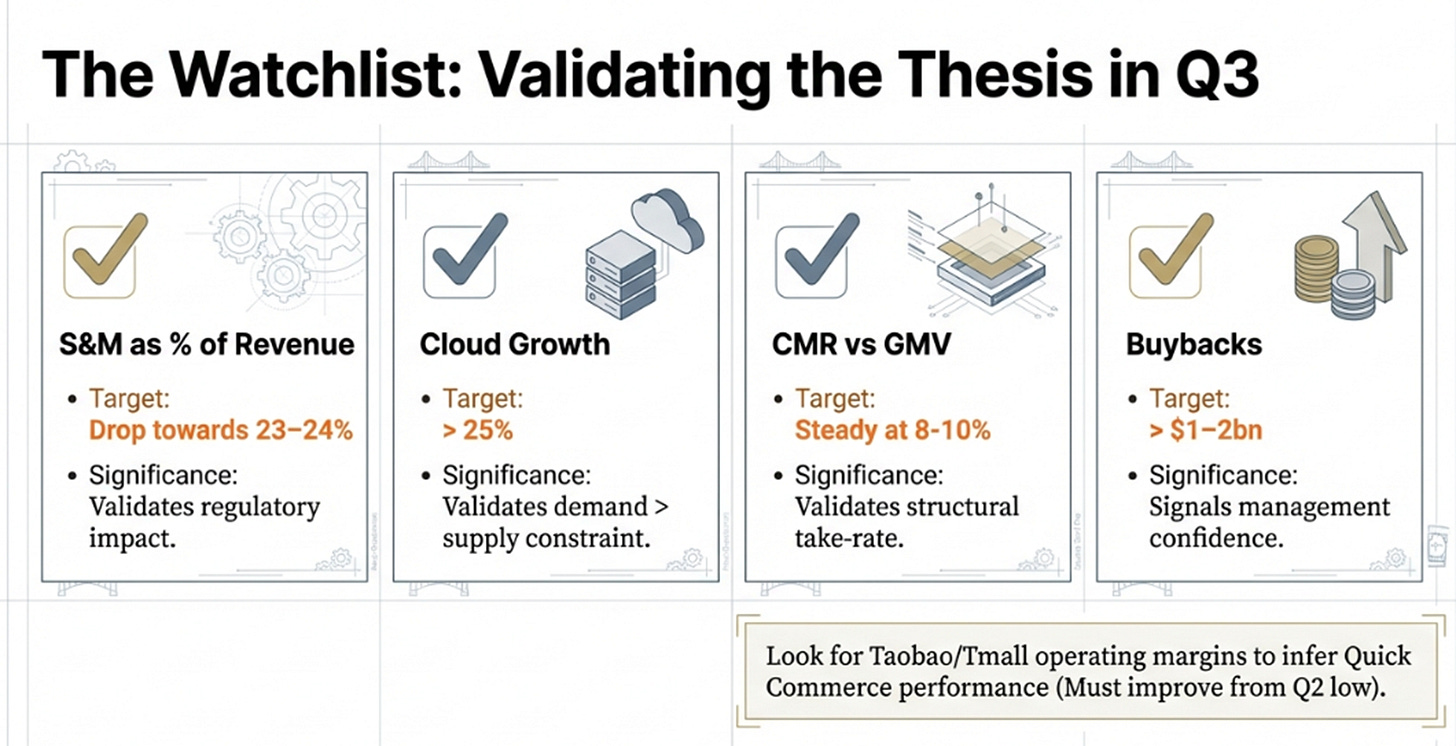

February’s Q3 earnings will answer the most immediate question: did January’s regulations actually moderate the subsidy war? The signal is sales and marketing as a percentage of revenue. In Q2 it was 26.6%. If Q3 shows movement toward 23-24%, the de-escalation is real. If it stays elevated or increases, either enforcement failed or competition found ways around the rules.

Three other metrics matter:

Cloud revenue growth needs to stay above 25% with stable or improving gross margins. Management said in Q2 that supply, not demand, is the constraint. If growth decelerates, that story breaks—it would mean either chip constraints are binding harder than expected or competition is intensifying. If margins compress while growth stays strong, it signals Alibaba is buying share rather than earning it.

Customer management revenue growth relative to GMV growth tests whether the Monetization Engine is structural or cyclical. In Q2, CMR grew 10% while subsidies intensified. If CMR holds at 8-10% growth as sales and marketing moderates, the take-rate improvements from Quanzhantui and the software service fee are real. If CMR collapses when spending falls, the whole monetization thesis was just share-taking through subsidies.

Quick commerce unit economics won’t be disclosed directly, but you can infer directionality from Taobao and Tmall segment operating margins. In Q2 they cratered 76%. If Q3 shows improvement, even modest, it validates that regulatory de-escalation is working. If margins compress further, quick commerce is still bleeding and the Frequency Layer remains financially destructive.

The buyback number tells you what management really believes. Token buybacks despite multi-year lows and $19 billion in authorization means they’re hoarding every dollar for defense and construction. Meaningful resumption—anything above $1-2 billion for the quarter—signals they see the worst behind them.

Twenty-Three Years Later

In 2003, Alibaba solved a trust problem and built an empire. The insight was simple: in China, becoming the trusted intermediary didn’t just win the market—it became the market.

In 2026, there’s a new trust problem, and the advantage has flipped. Chinese consumers trust AI to make decisions; Western consumers don’t. That Trust Chasm compresses the timeline from AI capability to AI monetization by years. Alibaba already has the trust—1.4 billion Alipay accounts, 930 million Taobao users—and they’ve connected it to an AI interface that can execute transactions, not just suggest them.

The strategic architecture is sound. The Compute Spine is capturing a forced migration to cloud as AI makes on-premise systems obsolete. The Frequency Layer is defending daily habit against Meituan. The Monetization Engine is extracting higher take-rates through AI-powered advertising that guarantees ROI.

The question was never whether the strategy made sense. It was whether the P&L could survive the construction.

Two months ago, I wrote that everything hinged on whether the next bills would be smaller. January’s regulatory intervention directly addresses that question by forcing industry-wide de-escalation of subsidy warfare. If the regulations work—if sales and marketing moderates, if quick commerce reaches profitability, if margins recover—then Alibaba pulled off something remarkable: they used a regulatory crisis to force a necessary transformation, then used new regulations to make that transformation financially sustainable.

We’ll know by summer whether they’re building a kingdom or just burning faster. The bills arrive in February.

Disclaimer:

The content does not constitute any kind of investment or financial advice. Kindly reach out to your advisor for any investment-related advice. Please refer to the tab “Legal | Disclaimer” to read the complete disclaimer.