Alphabet's 3Q25: The Intelligence Utility

How Alphabet Solved the Innovator’s Dilemma and Won the AI Race

TL;DR:

From AI Origins to Infrastructure Powerhouse: Alphabet’s Q3 2025 results prove it has transformed from a hesitant innovator into the core infrastructure provider for global AI, processing 1.3 quadrillion tokens/month and delivering $155B in Cloud backlog—a powerful testament to long-term strategic execution.

Solving the Innovator’s Dilemma at Scale: By merging DeepMind and Google Brain under Gemini and standardizing its AI architecture, Alphabet overcame fears of cannibalizing its Search business. Instead, AI expanded Search’s market with billions of new monetizable queries and 15% YoY revenue growth.

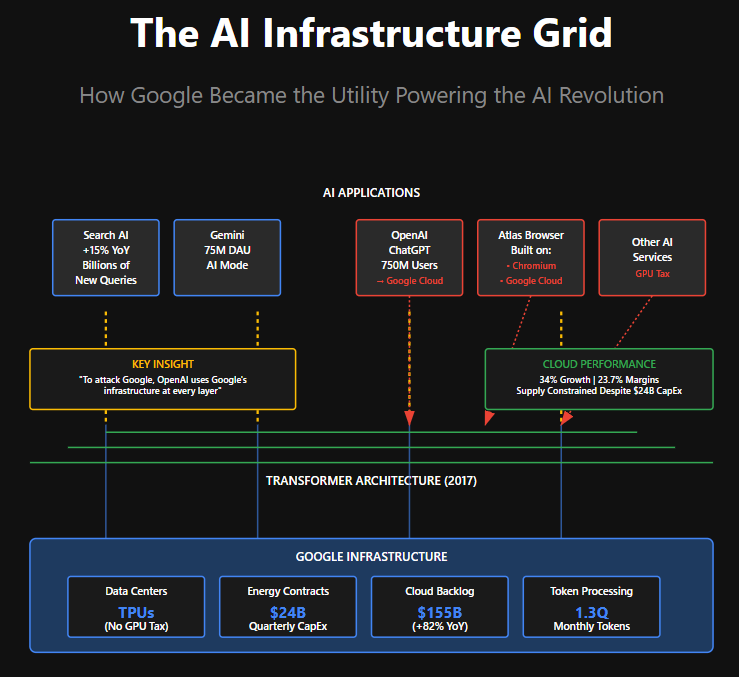

Grid vs. Socket – Google’s Strategic Moat: While OpenAI and others build applications, they still rely on Google’s infrastructure—from TPUs to data centers to Chromium. With unmatched scale, token economics, and self-funded growth, Alphabet has built the grid that powers the AI revolution.

The First AI Company

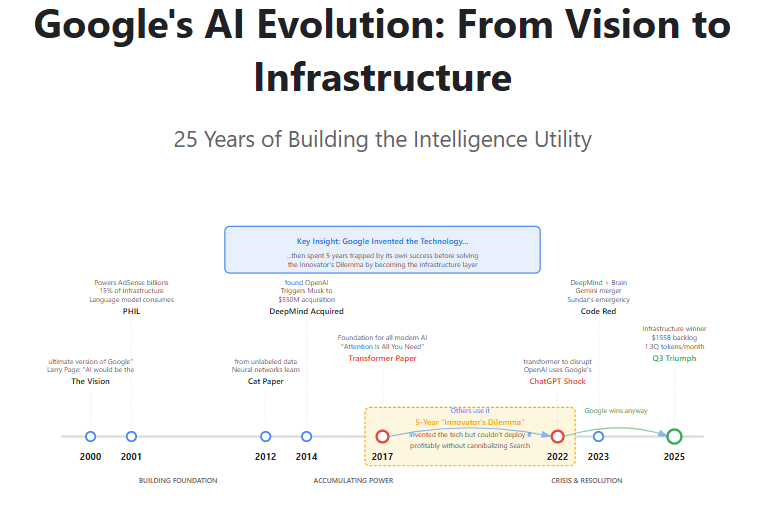

Before it was an advertising giant, Google was an AI company. This isn’t revisionist history. In 2000, Larry Page stated explicitly: “Artificial intelligence would be the ultimate version of Google.” That vision manifested early. In 2001, a language model called PHIL became so computationally expensive it consumed 15% of Google’s entire infrastructure. But PHIL was worth it—it powered features like “Did you mean?” spelling correction and became the engine behind the multi-billion dollar AdSense business overnight.

For the next decade, Google built the world’s most impressive collection of bespoke AI systems. They hired nearly every significant mind in the field—Geoff Hinton, Ilya Sutskever, Jeff Dean. Google Brain’s 2012 “cat paper” proved that massive neural networks could learn concepts from unlabeled data, supercharging YouTube’s recommendation engine. When Hinton’s team achieved breakthrough image recognition results with AlexNet in 2012, Google acquired their startup immediately.

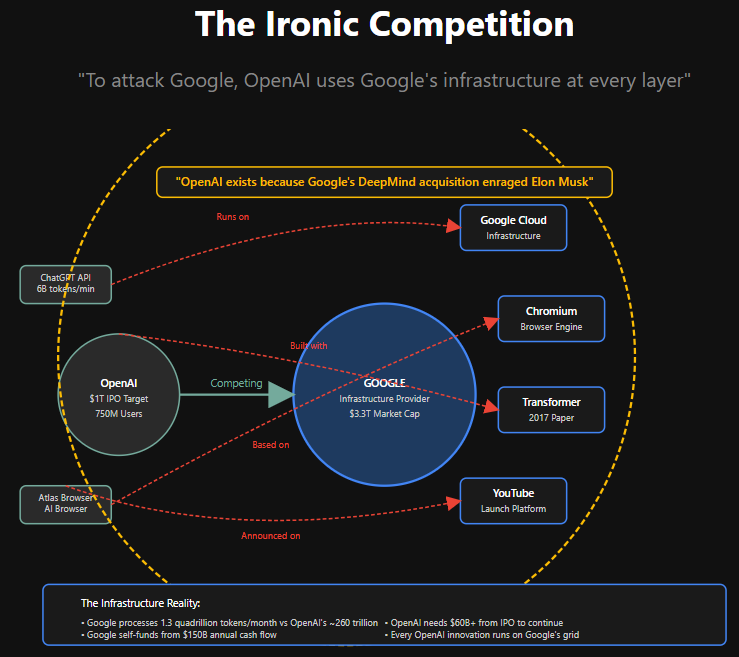

In 2014, Google acquired DeepMind for $550 million, a research lab focused on achieving Artificial General Intelligence. The acquisition infuriated early DeepMind investor Elon Musk, who feared Google was creating an AI monopoly. Musk’s reaction directly led him and Sam Altman to found OpenAI in 2015 as a non-profit competitor. The great challenger, in other words, was an unintended creation of the incumbent.

Then in 2017, Google published “Attention Is All You Need”—the transformer architecture that became the foundation for every modern AI system. Like tossing a magic spellbook into a crowd. OpenAI, facing its own funding crisis after Musk’s departure, went all-in on transformers, leading to the GPT series.

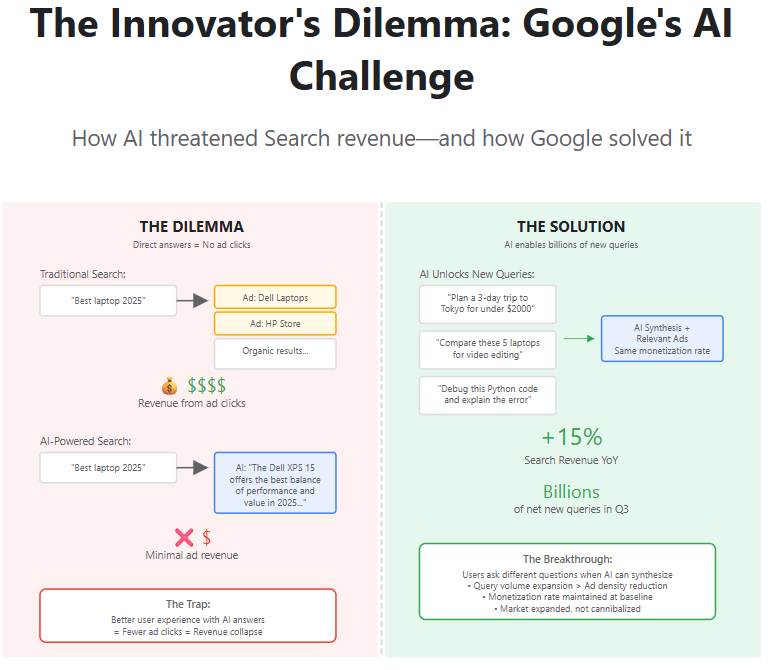

Google had invented the breakthrough but couldn’t figure out how to deploy it profitably. A chatbot providing direct answers threatened its lucrative Search ad model. An AI that could hallucinate was too risky for a trusted brand. For five years, Google was trapped in the most perfect, high-stakes case of the Innovator’s Dilemma ever witnessed.

ChatGPT’s launch in November 2022 wasn’t the start of the war—it was the moment the dilemma came due.

This is the only lens through which to understand Alphabet’s third quarter of 2025. The numbers don’t just represent strong financial performance. They represent a verdict. This is the tangible, quantitative proof that Alphabet, having stared into the abyss of its own dilemma, has successfully executed its solution.

The Code Red and the Solution

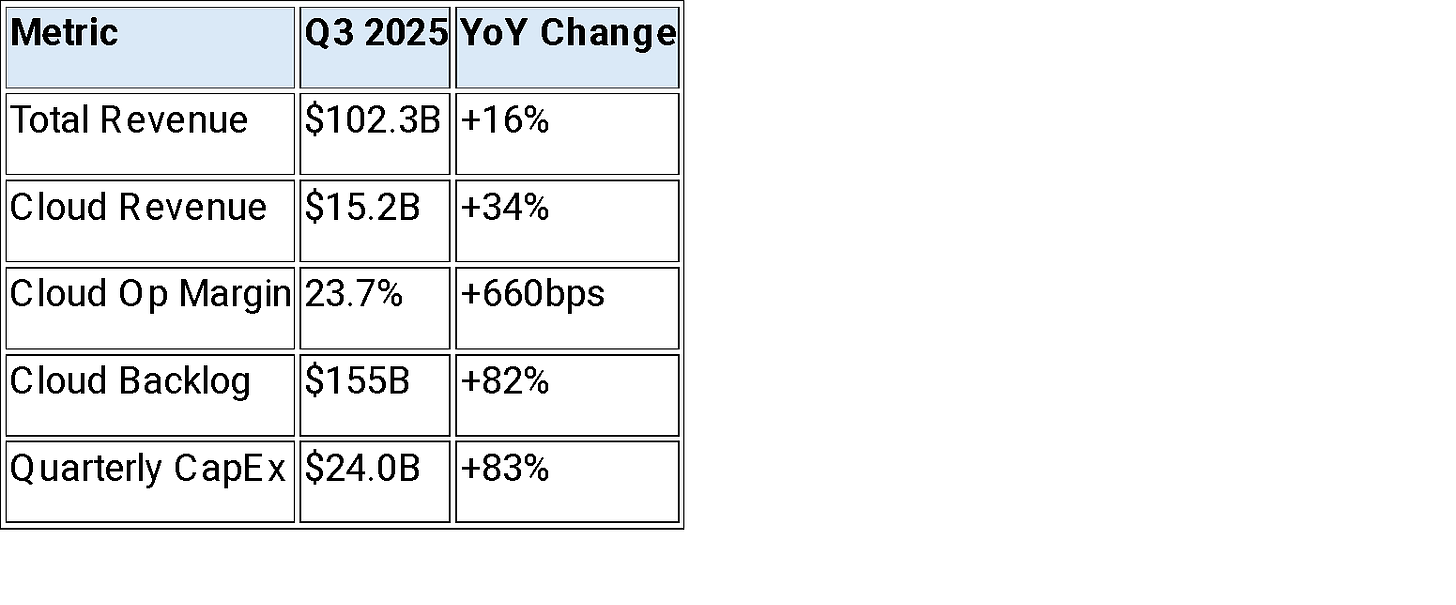

From Bloomberg, October 29, 2025: “Alphabet Inc. delivered robust third-quarter results that handily beat Wall Street expectations, with revenue reaching $102.3 billion. Google Cloud achieved 34% growth to $15.2 billion with operating margins expanding dramatically to 23.7%.”

My first thought upon reading these results was that they tell a story far beyond a typical earnings beat. This is what solving the Innovator’s Dilemma looks like on a balance sheet.

Sundar Pichai’s “Code Red” in December 2022 was the moment of decision. The rushed response, Bard, was widely seen as inferior and damaged Google’s reputation. But Pichai then made two culturally wrenching choices: he merged the rival factions of Google Brain and DeepMind under Demis Hassabis, and standardized the entire company on a single model, Gemini.

This quarter’s results are the payoff.

The elephant learned to ship at AI speed.

The number I believe deserves the most emphasis is the Cloud backlog. $155 billion represents 2.5 years of current quarterly revenue. These are multi-year commitments from enterprises that have decided Google’s infrastructure is essential.

CFO Anat Ashkenazi explained on the call: “While we have been working hard to increase capacity, we still expect to remain in a tight demand-supply environment in Q4 and 2026.”

Supply-constrained despite spending $24 billion in a quarter on capital expenditures.

That’s not commodity infrastructure. That’s differentiated capacity customers cannot get elsewhere.

What I find even more revealing, though, is the margin expansion. Cloud operating margins jumped from 17.1% to 23.7% while revenue grew 34%. This is the direct result of Google’s structural cost advantage: TPUs, its custom AI chips. As the Acquired podcast noted, competitors pay NVIDIA’s roughly 80% gross margin on entire GPU systems. Google’s internal cost structure for TPUs gives it a profound “tokens-per-dollar” advantage at the system level.

It’s not just a cheaper chip—it’s avoiding the full “GPU tax” that everyone else pays.

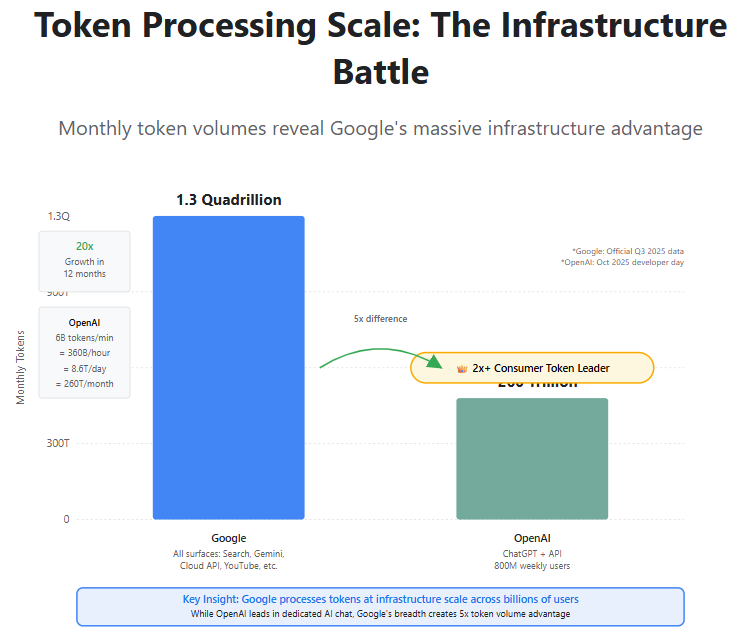

Sundar Pichai mentioned something in prepared remarks that got almost no analyst questions but that I think matters enormously: “In July, we announced that we processed 980 trillion monthly tokens across all our surfaces. We are now processing over 1.3 quadrillion monthly tokens, more than 20x growth in a year.”

1.3 quadrillion tokens monthly. Every token is a training example flowing through Google’s infrastructure—Search queries, YouTube videos, Maps navigation, Android interactions. This isn’t just scale; it’s breadth of data that competitors cannot replicate. OpenAI has 750 million ChatGPT users generating conversational data in a narrow context. Google has 2+ billion users generating intent data, behavioral data, visual data, location data across a dozen surfaces simultaneously.

The Search business—the source of the original dilemma—is now being enhanced by the solution. Revenue grew 15% YoY. Philipp Schindler noted that “AI Max unlocked billions of net new queries” in Q3 alone.

The narrative was that ChatGPT would cannibalize Search. Instead, AI expanded Search’s addressable market. Users ask different types of questions when AI can synthesize complex answers.

Pichai addressed monetization directly: “For AI Overviews, even at our current baseline of ads, we see the monetization at approximately the same rate” as traditional search. That language has appeared for two consecutive quarters, meaning they haven’t solved higher ad density in AI responses yet. But volume growth compensates—billions of new queries at existing rates drives revenue while they optimize.

Google is funding this entire build from operations. The company generated $24.5 billion in free cash flow this quarter. Ashkenazi guided 2025 capital expenditures to $91-93 billion and noted 2026 would be “significantly higher.”

All funded from the $150+ billion in annual operating cash flow the business generates.

No IPO required. No capital markets dependency.

The Ironic Competition

The strategic landscape is a duel between two models born from the same source. On one side is Alphabet’s self-funded Fortress. On the other is OpenAI’s capital-intensive Web—which, remember, exists because Google’s DeepMind acquisition so enraged Elon Musk that he organized the founding dinner at San Francisco’s Rosewood Hotel.

The irony deepens. Even today, OpenAI depends on the Fortress it’s trying to disrupt. As Liam Fallen noted on LinkedIn about OpenAI’s Atlas browser: “Runs on Google Cloud. Uses Google’s transformers. Announced on Google’s YouTube. It’s built using Google’s Chromium.”

To attack Google, OpenAI uses Google’s infrastructure at every layer.

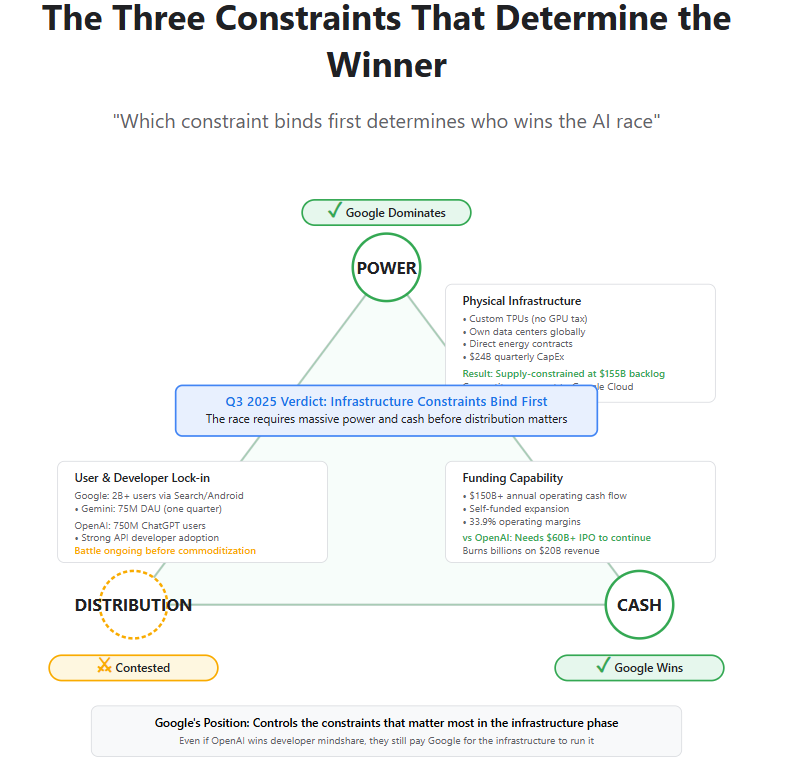

This reveals something fundamental about competitive dynamics. There’s a framework I find useful: which constraint binds first determines the winner. The three constraints are power, cash, and distribution.

Power

Power means physical infrastructure—data centers, energy contracts, chip supply. If power binds first, advantage goes to whoever owns infrastructure and achieves the best economics per watt. Google designs its own chips (avoiding the GPU tax), builds its own data centers, negotiates power contracts directly.

OpenAI rents data centers from Oracle, buys chips from NVIDIA and AMD, depends on others for power supply.

The Q3 backlog and supply constraints show power is binding for Google—but in a positive way. Demand exceeds supply because they’ve achieved cost advantages competitors cannot match. The $155 billion backlog functions like power purchase agreements—long-dated commitments that derisk massive infrastructure spending.

Cash

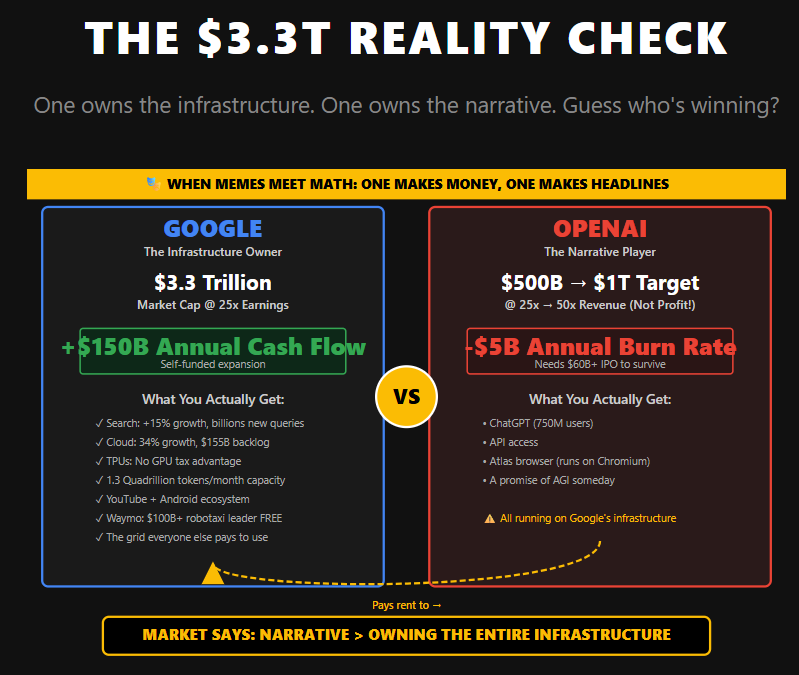

Cash means sustained funding capability. Google generates $150+ billion in operating cash flow annually and remains highly profitable. OpenAI, according to Reuters reporting from October 29, burns billions annually on $20 billion in revenue and is preparing “an initial public offering that could value the company at up to $1 trillion” with plans to “raise $60 billion at the low end.”

One company funds the race from profits. The other needs a historically large IPO to continue.

Distribution

Distribution means user and developer lock-in before underlying technology commoditizes. OpenAI has 750 million ChatGPT users and strong API adoption. Google has 2+ billion users already interacting with AI through Search, AI Mode (75 million daily active users within one quarter of launch), YouTube, Maps, Workspace.

But the dependency chain—Atlas running on Google infrastructure—suggests Google’s multi-layered approach is working.

What the Q3 results show is which constraints favor whom. Power and cash clearly favor the infrastructure owner. Distribution remains contested, but even that contest happens on Google’s grid.

The Depreciation Bill

There is, of course, a challenge ahead. Depreciation expense grew 41% YoY in Q3. With capital expenditures doubling, depreciation will accelerate through 2026. Ashkenazi mentioned depreciation three times on the earnings call—preparing investors for margin pressure.

Operating margin was 33.9% excluding a one-time European Commission fine, down from 35%+ historically.

The bet Google is making: accept temporary margin compression toward 31-32% to build infrastructure competitors cannot replicate.

This is where the PHIL story from 2001 matters. Google has a playbook for this: consume massive infrastructure to build AI capabilities, then monetize them at scale. PHIL ate 15% of infrastructure to power AdSense. Today’s CapEx surge is the same pattern at vastly larger scale—building the grid that powers the next decade of products.

The constraint framework suggests this works. Competitors paying the GPU tax cannot match Google’s unit economics. As long as Google maintains its tokens-per-dollar advantage, it can sustain margins while competitors struggle with higher costs.

If Cloud growth sustains above 30% and margins hold above 20%, the investment pays off. If margins compress further or Cloud decelerates, the strategy becomes questionable. That’s the test for 2026.

The Valuation and the Hidden Asset

Google trades at $3.3 trillion market capitalization and 25x forward price-to-earnings based on 2026 estimates. That’s fair for a company growing revenue mid-teens with proven profitability. It’s not cheap, but it’s not expensive.

Microsoft, with similar Cloud dynamics, trades at 30x.

But what I think this valuation doesn’t include is Waymo. As the Acquired podcast framed it, Waymo could be a “Google-sized business within Google.” The division is now doing more rides than Lyft in San Francisco, has driven over 100 million autonomous miles, and its studies show 91% fewer crashes with serious injuries compared to human drivers.

This is no longer a science project. It’s a commercial reality operating at scale.

The market is getting Waymo for free. It’s buried in Other Bets, which reported declining revenue in Q3 despite Waymo’s expansion. Other experimental projects in that segment obscure Waymo’s progress. But autonomous transportation represents a multi-hundred-billion-dollar market, and Google has a multi-year technical lead.

Compare Google’s grounded valuation to OpenAI’s $1 trillion IPO target on $20 billion revenue—50x sales for an unprofitable company. This isn’t about comparing businesses directly; they operate at different layers. But it reveals market psychology.

Google at 25x 2026 PE reflects proven infrastructure execution and solved Innovator’s Dilemma. OpenAI at 50x sales reflects speculation on platform winner-take-all dynamics.

The question for late 2026, when OpenAI attempts that IPO: does the platform premium persist when the platform depends on infrastructure below?

Or does the market recognize that when constraints bind—power, cash, sustainability—the grid operator has structural advantages the socket cannot overcome?

The Arc Completes

In 1890s factories, productivity revolutions from electricity came not from bigger motors but from distributed power enabling workflow redesign. Infrastructure providers—utilities—captured steady returns. Innovation premiums went to companies that redesigned manufacturing around cheap electricity.

What I see in Google’s Q3 is the AI equivalent. Google gave away the transformer architecture in 2017 and let the world build on it. While competitors focused on applications, Google built the grid: TPUs, data centers, power contracts—the infrastructure to deliver intelligence at scale.

The narrative whiplash is complete. “Google is finished” in 2023 morphed into Q3 2025 results showing Search accelerating (+15%), Cloud exploding with supply constraints (+34%, 24% margins), token processing at unprecedented scale (1.3 quadrillion monthly), and the entire build funded from $150+ billion operating cash flow.

Even OpenAI’s Atlas browser—designed to showcase AI’s future—runs on Google Cloud, uses Google’s transformer architecture, launches on YouTube, and builds on Chromium.

As that viral post captured: “Be me, Google. Got bored. Dropped the Transformer into the world. Boom. Chaos. Then I wake up. Search growth back. Gemini dominates. GPC exploding. The race is on again. And I’m still the one setting the track.”

Larry Page’s 2000 vision—”Artificial intelligence would be the ultimate version of Google”—is being realized 25 years later. The company that invented the technology, got trapped by the Innovator’s Dilemma, then made the hard choices to solve it, is now the infrastructure provider for the intelligence economy.

The next 18 months test whether this persists. Watch Cloud backlog conversion, operating margins through the depreciation wave, third-party Search traffic data, and OpenAI’s IPO reception.

But Q3 established something I think is critical: when constraints bind—when power economics and cash sustainability matter more than narrative—the company that owns the grid has advantages the socket cannot easily overcome.

Google tossed the spellbook into the crowd in 2017. Eight years later, everyone’s still reading from it. But they’re reading on infrastructure Google built, paying the GPU tax Google avoids, and depending on distribution Google controls.

That might be the real magic trick—not the transformer itself, but building the grid that makes transformers profitable at global scale.

The dilemma is solved. The utility is online. And the company that’s been an AI company since 2000 is finally getting credit for it.

Disclaimer:

The content does not constitute any kind of investment or financial advice. Kindly reach out to your advisor for any investment-related advice. Please refer to the tab “Legal | Disclaimer” to read the complete disclaimer.