Amazon Q4 2025: Record execution, meets a $200B capital commitment

Q4 execution was flawless, the stock fell because the company just rewrote its own capital playbook.

TL;DR:

Amazon just delivered its best quarter in years across AWS, ads, and retail margins, and still got punished.

The reason is simple: $200B of 2026 capex turns free cash flow meaningfully negative.

The real story: Amazon is betting AI is supply-constrained, and it’s racing to own the bottleneck (power, chips, capacity).

Amazon’s Risky Bet, Again

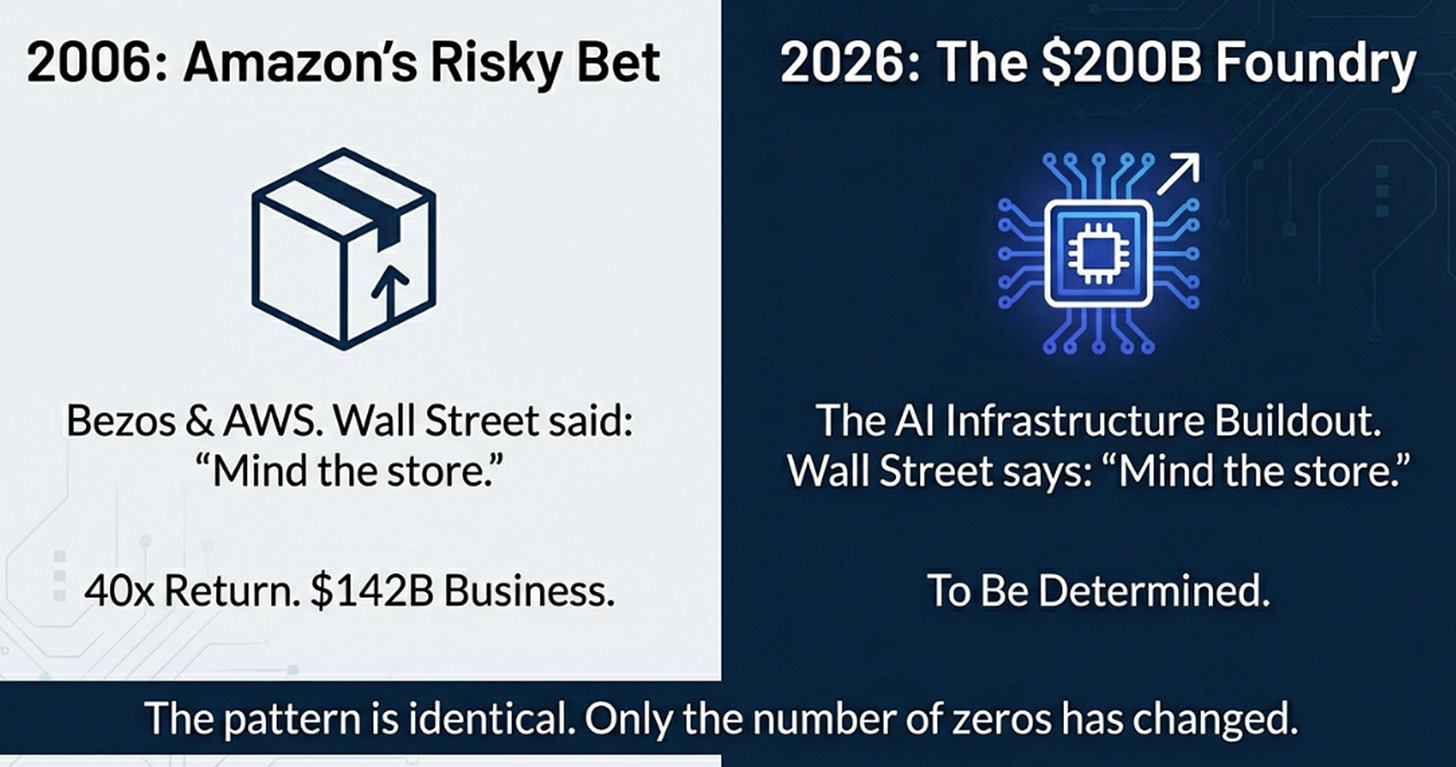

In October 2006, BusinessWeek put Jeff Bezos on its cover holding a cardboard box. The headline read “Amazon’s Risky Bet.” The story inside described a company still struggling with a marginally profitable retail business embarking on what seemed like an entirely unrelated venture: selling its own storage and computing infrastructure to other companies. One Wall Street analyst called the investment “probably more of a distraction than anything else.” Even Tim O’Reilly, who recognized the strategy early, called Amazon a “dark horse.”

That dark horse built Amazon Web Services into a $142 billion-a-year business running at 35% operating margins, the most profitable division in the company’s history, and arguably the most important infrastructure platform of the internet era.

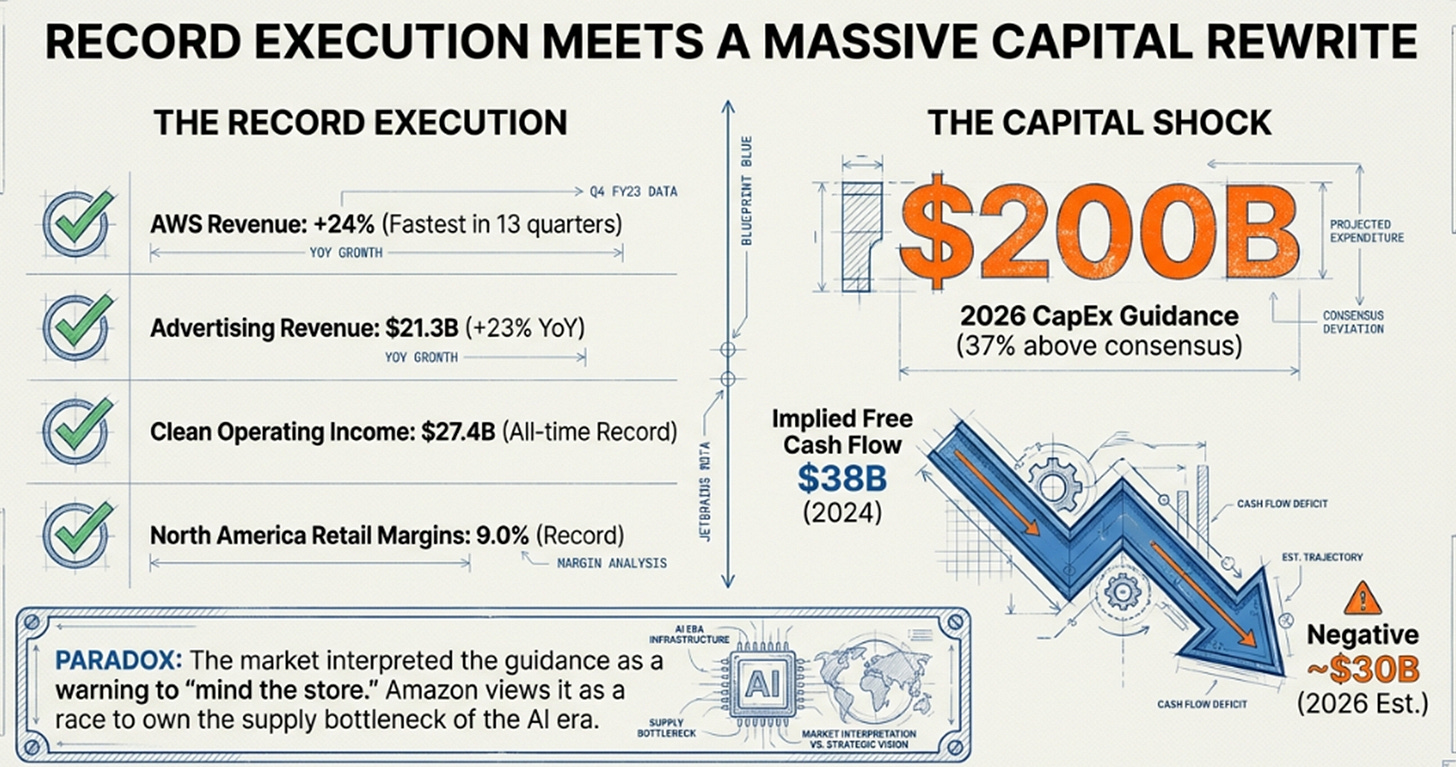

Twenty years later, the pattern is repeating. On February 5, 2026, Amazon reported what was, by virtually every operational measure, its strongest quarter in years. AWS revenue grew 24%, the fastest rate in thirteen quarters. Advertising hit $21.3 billion, up 23%. North America reached record operating margins. The backlog of committed cloud contracts swelled to $244 billion, growing 40% YoY. And after adjusting for $2.4 billion in one-time charges , an Italian tax settlement, severance costs for 30,000 employees, and physical store impairments , clean operating income came in at $27.4 billion, well above what the business had ever produced.

The stock dropped nearly 5%+.

The reason was a single number: Amazon guided 2026 capital expenditure to approximately $200 billion. That figure exceeded the Street consensus of $146 billion by $54 billion, or 37%. It implied that free cash flow, which had already collapsed from $38 billion in fiscal 2024 to just $11 billion in 2025, would turn meaningfully negative in 2026 , perhaps to the tune of negative $25 to $35 billion. Within hours, Amazon filed paperwork with the SEC indicating it might raise equity or debt to fund the buildout.

The market’s message was clear: just mind the store.

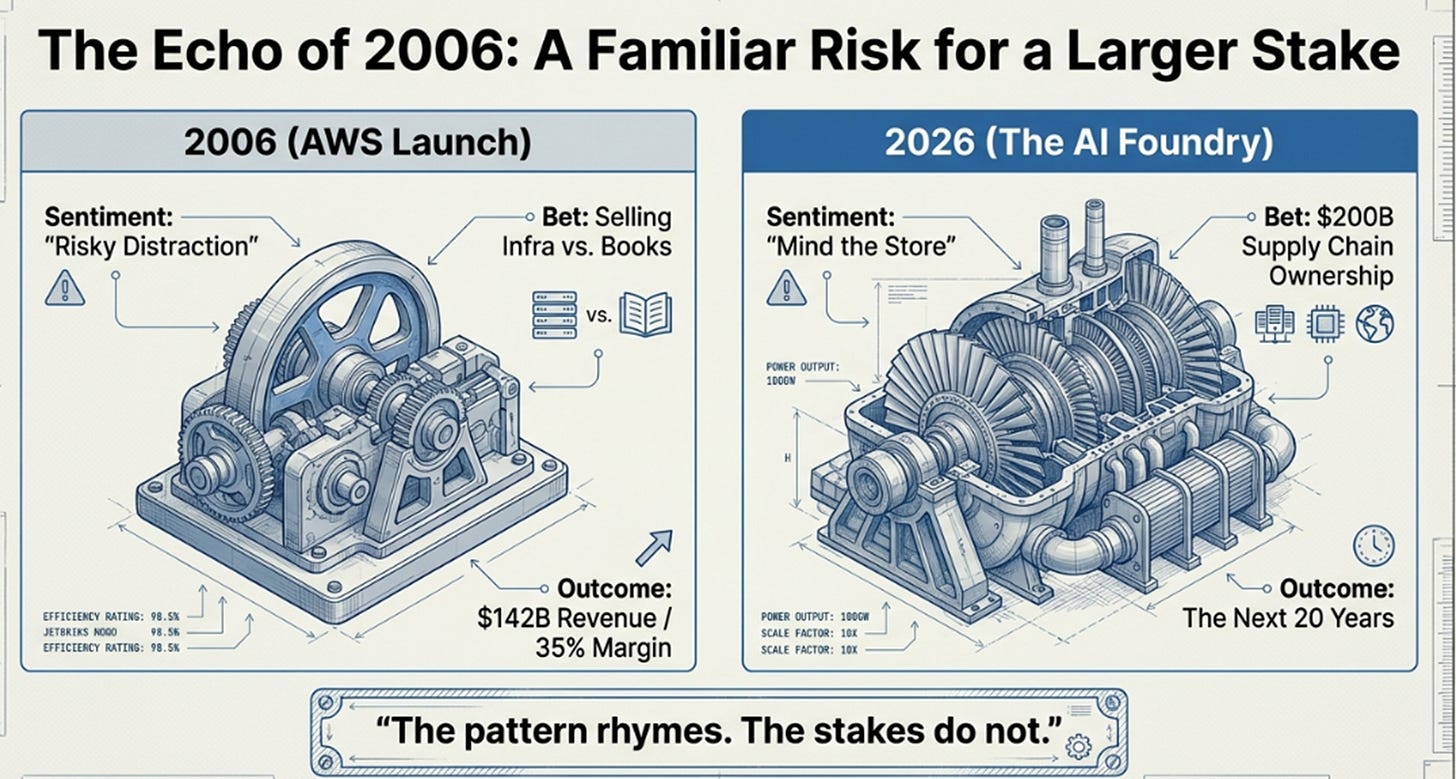

The question is whether that message is any more correct now than it was in 2006.

Engine Room and Foundry, Revisited

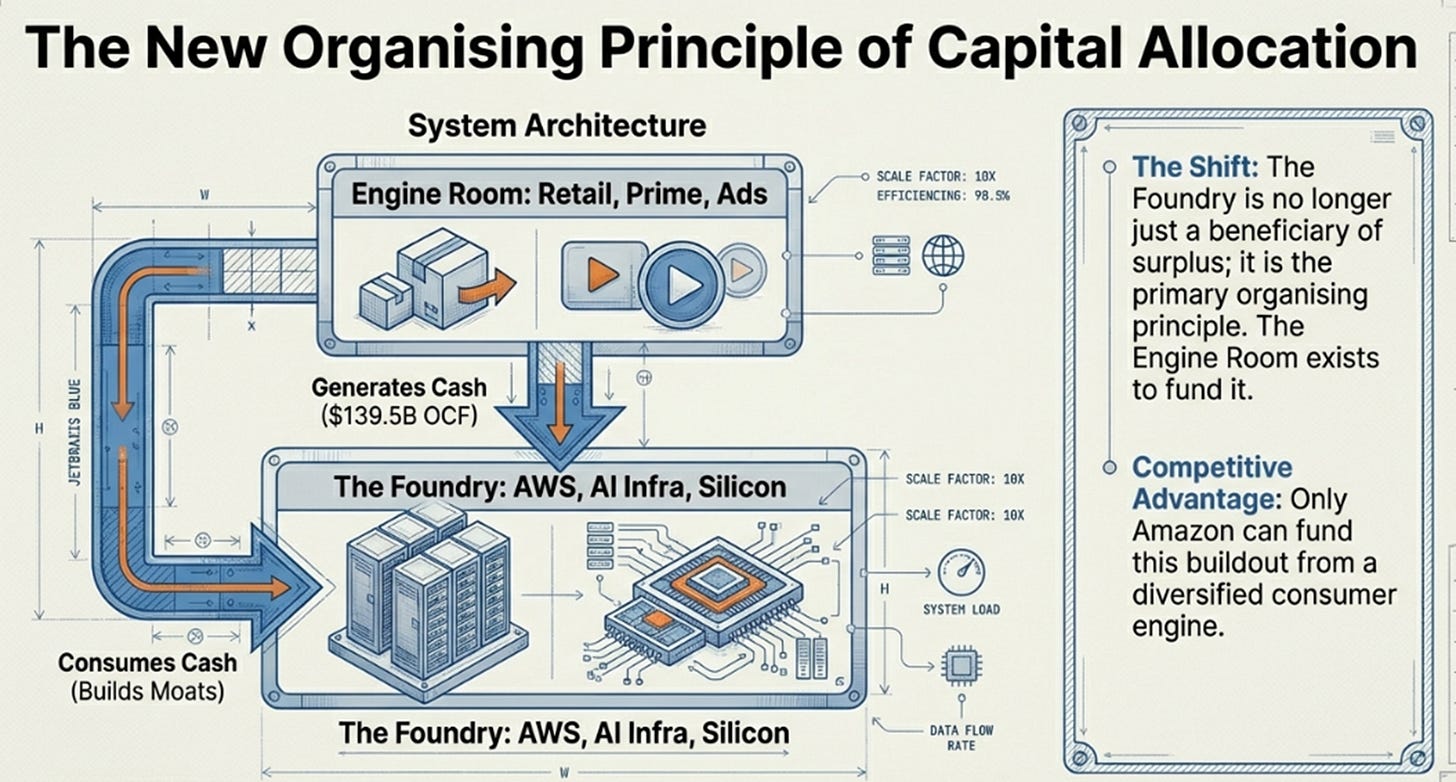

In our Q3 update, we described Amazon’s structural advantage as a two-part machine. The Engine Room, retail commerce, Prime subscriptions, and advertising, generates enormous and growing cash flows. The Foundry, AWS, AI infrastructure, custom silicon, absorbs that cash and converts it into long-duration competitive advantages. The thesis was that Amazon’s unique ability to fund the Foundry from a diversified Engine Room gave it a structural edge that pure-play cloud or AI companies could not replicate.

Q4 confirmed that framework, but it also revealed something we underestimated: the Foundry is no longer the beneficiary of the Engine Room’s surplus. It is now the organizing principle of the entire company’s capital allocation.

This is a meaningful shift. When AWS launched in 2006, it was a side experiment funded by retail cash flow. By 2015, it was the profit engine. By 2020, it was the reason Amazon’s valuation made any sense at all. The same structural transition is happening again, one level up. The AI Foundry is to today’s Amazon what AWS was to the Amazon of 2006 , the part of the business that looks like a drag on the financials right now, but that could define the company for the next two decades.

The critical difference is scale. AWS launched with minimal capital expenditure. The AI Foundry requires $200 billion in a single year. That means the Engine Room has to be stronger than it has ever been.

And it is.

The Engine Room at Full Power

The argument that Amazon can sustain a negative free cash flow year rests entirely on the Engine Room’s ability to keep generating cash at scale. Q4 provides the strongest evidence yet that it can.

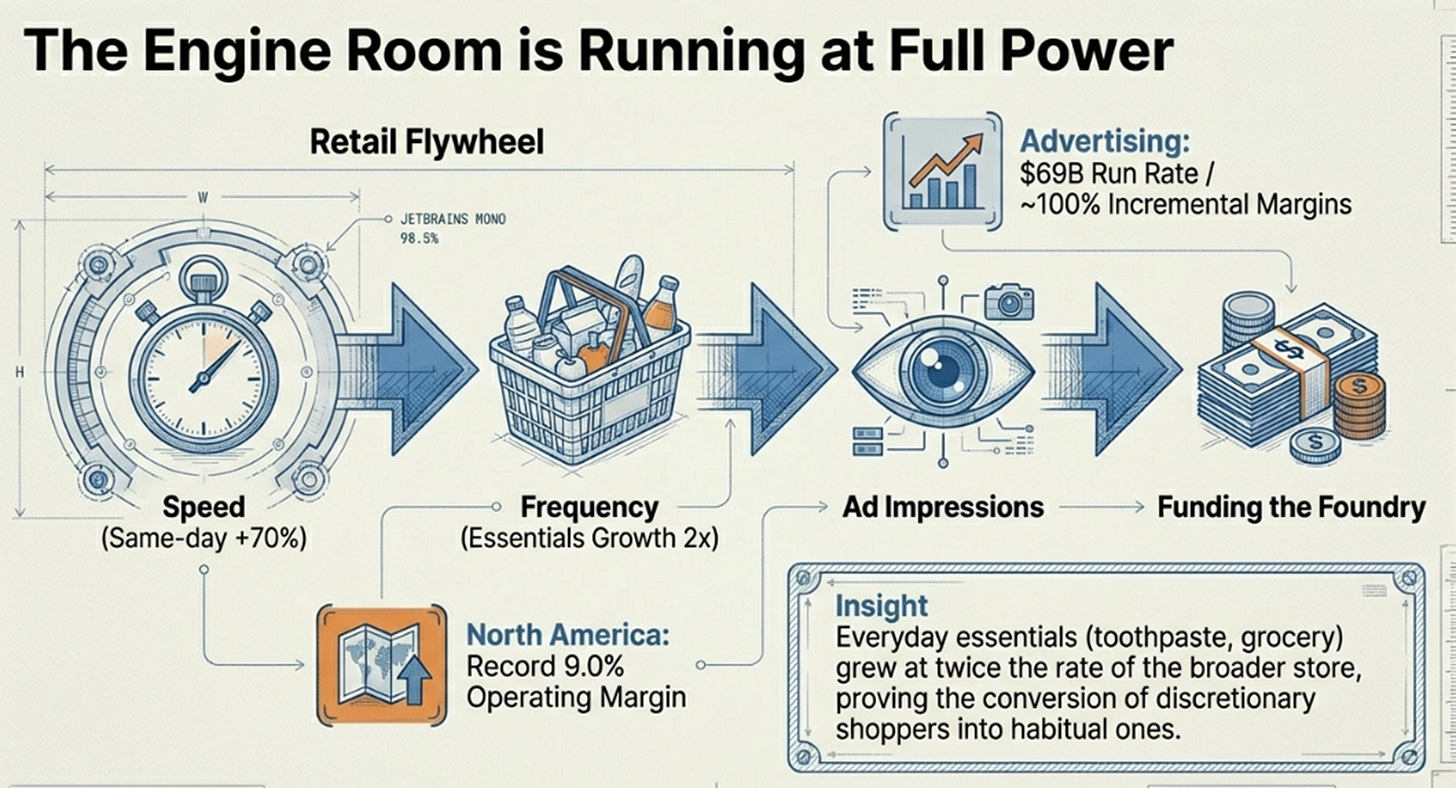

Start with advertising, which has quietly become Amazon’s most important margin engine. The segment generated $21.3 billion in Q4, up 23% YoY, and is now running at nearly $69 billion annually. What makes advertising structurally significant is not just the growth rate but the margin profile: these are near-100% incremental margins layered on top of existing retail traffic. Every dollar of advertising revenue drops almost entirely to operating income. No other business at Amazon’s scale compounds at this rate with this profitability, and it is this business, more than AWS, more than Prime, that funds the operating cash flow surplus the Foundry consumes.

North America retail, meanwhile, reached its operational peak. Clean operating margins hit a record 9.0% in Q4, driven by two mutually reinforcing dynamics: delivery speed and purchase frequency. Same-day delivery grew 70% YoY. The “everyday essentials” category , toothpaste, paper towels, groceries, grew at twice the rate of the broader store.

Faster delivery converts discretionary shoppers into habitual ones, and habitual shoppers buy essentials, which are higher-frequency and lower-return-rate than general merchandise. This is the flywheel at its most efficient: speed drives frequency, frequency drives advertising impressions, and advertising impressions fund the Foundry.

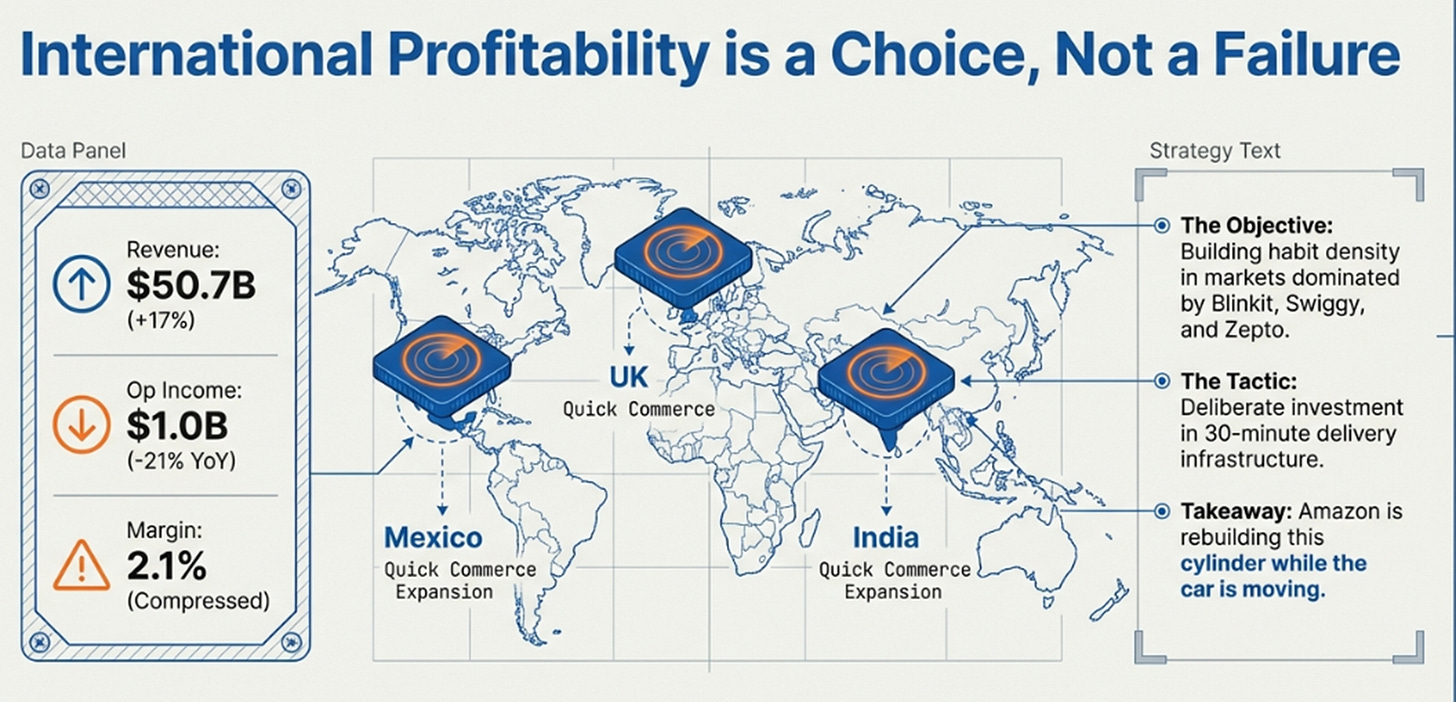

The deliberate exception is international. Revenue grew 17% to $50.7 billion, but operating income declined 21% to just $1.0 billion, a 2.1% margin. This is not a failure; it is a choice. Amazon is investing aggressively in quick commerce, thirty-minute delivery in India through Amazon Now, expansion into the UK and Mexico, and deliberately accepting lower margins to build frequency habits in markets where Blinkit, Swiggy, and Zepto currently dominate. Management flagged that Q1 2026 would see further margin pressure from “sharper prices“ and quick commerce investment. The international business is the Engine Room’s one cylinder that is being rebuilt while the car is moving.

Together, these businesses generated $139.5 billion in trailing twelve-month operating cash flow, up 20% YoY. The funding mechanism is not a theory. It is the most powerful cash generation engine in consumer technology, and Q4 demonstrated that it is accelerating, not fatiguing, at the exact moment the Foundry needs it most.

The Supply-Side Bet

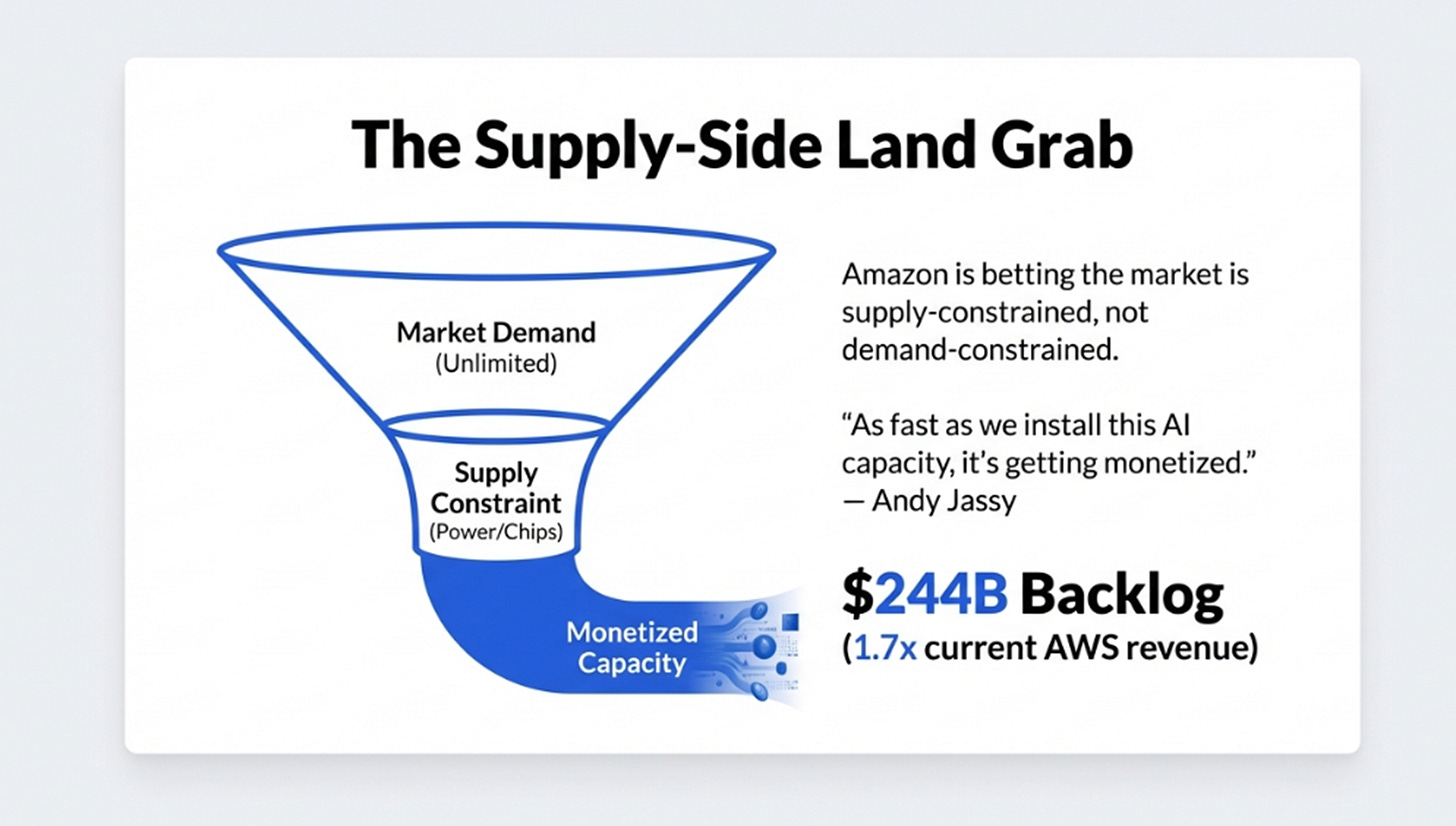

Most narratives about AI investment focus on the demand side: will enterprises actually adopt AI at scale? Amazon’s bet is different and more specific. The thesis embedded in the $200 billion commitment is that the binding constraint on AI is not demand , it is supply. Power. Chips. Data center capacity. And whoever removes the supply constraint fastest will capture a disproportionate share of the market.

This reframes the entire capex discussion. The $200 billion is not speculative spending in hopes that demand materializes. It is a land grab in a supply-constrained market where Amazon believes , with evidence , that every unit of capacity is being absorbed as fast as it can be deployed. Andy Jassy said as much on the earnings call:

“As fast as we install this AI capacity, it’s getting monetized.”

The $244 billion backlog, growing 40% YoY and representing 1.7 times current annual AWS revenue, is the strongest single data point supporting that claim.

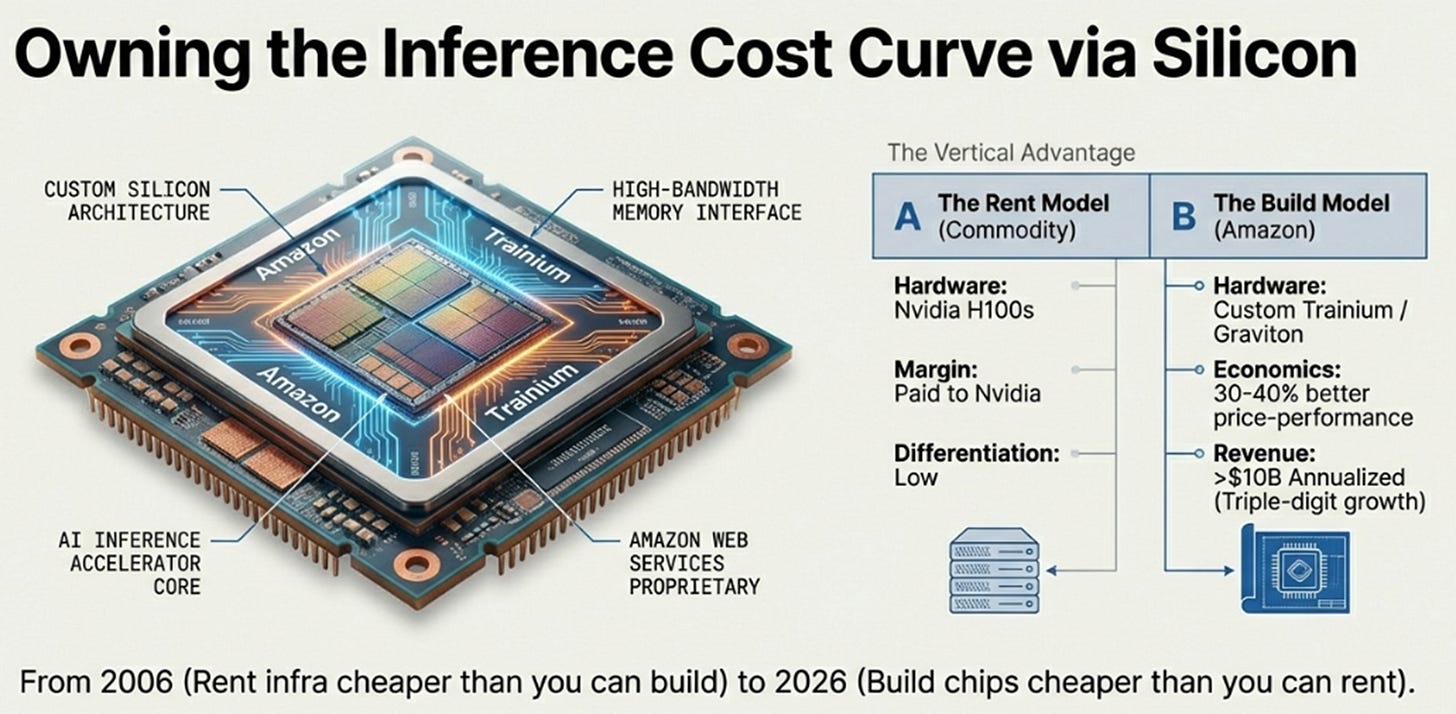

But the supply-side bet has a second, less discussed dimension: silicon. Amazon disclosed for the first time that its custom chip business , Trainium AI accelerators and Graviton CPUs, has crossed $10 billion in annualized revenue, growing at triple-digit rates. Trainium2 is fully subscribed, with 1.4 million chips deployed. Trainium3 is already in production, and management expects most of that supply to be committed by mid-2026.

This matters because it represents Amazon’s attempt to own the inference cost curve. The difference between renting Nvidia GPUs at market prices and running your own silicon at 30–40% better price-performance is the difference between operating a commodity cloud utility and building a structurally advantaged business. In 2006, the key insight was that Amazon could rent its own infrastructure to others more cheaply than they could build it themselves. In 2026, the parallel insight is that Amazon can build its own chips to run that infrastructure more cheaply than anyone who depends on Nvidia.

The skepticism, however, is legitimate. Trainium’s adoption remains concentrated, Anthropic is the anchor tenant, and the broader developer ecosystem still overwhelmingly runs on Nvidia’s CUDA platform. And the competitive picture is mixed: while AWS grew 24%, Microsoft Azure grew 39% and Google Cloud surged 48%, albeit on smaller bases. AWS adds more absolute dollars per quarter than either rival, but the percentage growth gap is real and widening.

The 2006 bet required millions. This one requires hundreds of billions. The pattern rhymes. The stakes do not.

The Depreciation Window

The market is focused on free cash flow turning negative. That is a real concern, but it is not the most important dynamic. The more consequential effect of $200 billion in annual capex is what happens to reported earnings over the next two to three years as depreciation flows through the income statement.

The accounting mechanics are straightforward. Amazon spends the cash upfront, but GAAP spreads that cost over five to seven years as depreciation expense. In fiscal 2025, Amazon recorded $65.8 billion in depreciation and amortization. If $200 billion in capex comes online in 2026, depreciation likely steps to $85–95 billion that year and could reach $110–130 billion by 2027. This creates a window in which Amazon’s reported profitability may deteriorate even if the underlying business is performing well, simply because the accounting cost of prior investments is arriving with a lag.

This is the time-horizon problem in its purest form. Short-term investors look at the financial statements over the next six to eight quarters and see collapsing free cash flow, compressed margins, and rising depreciation. Long-term investors look at $244 billion in contracted demand, a custom silicon cost advantage that compounds, and an advertising business generating $69 billion a year at extraordinary margins. Both cohorts are looking at the same numbers. They reach opposite conclusions because they are evaluating different time horizons.

The reason Amazon can endure this window, and this is where the Engine Room framework becomes essential, is that depreciation hits the income statement, not the cash register. Operating cash flow remains approximately $140 billion and growing. As long as retail and advertising continue to generate cash, the Foundry can absorb the accounting pain. This was also true between 2006 and 2010, when AWS capital expenditure looked like a needless drag on an already thin-margin retail business , right up until the moment it became the most profitable part of the company.

Prove-It Mode

Amazon has entered what the Street is now calling “prove-it mode.” The demand narrative is established. The capital commitment is made. What the market requires next is conversion, capex turning into revenue, revenue turning into margins, and margins turning into returns on invested capital.

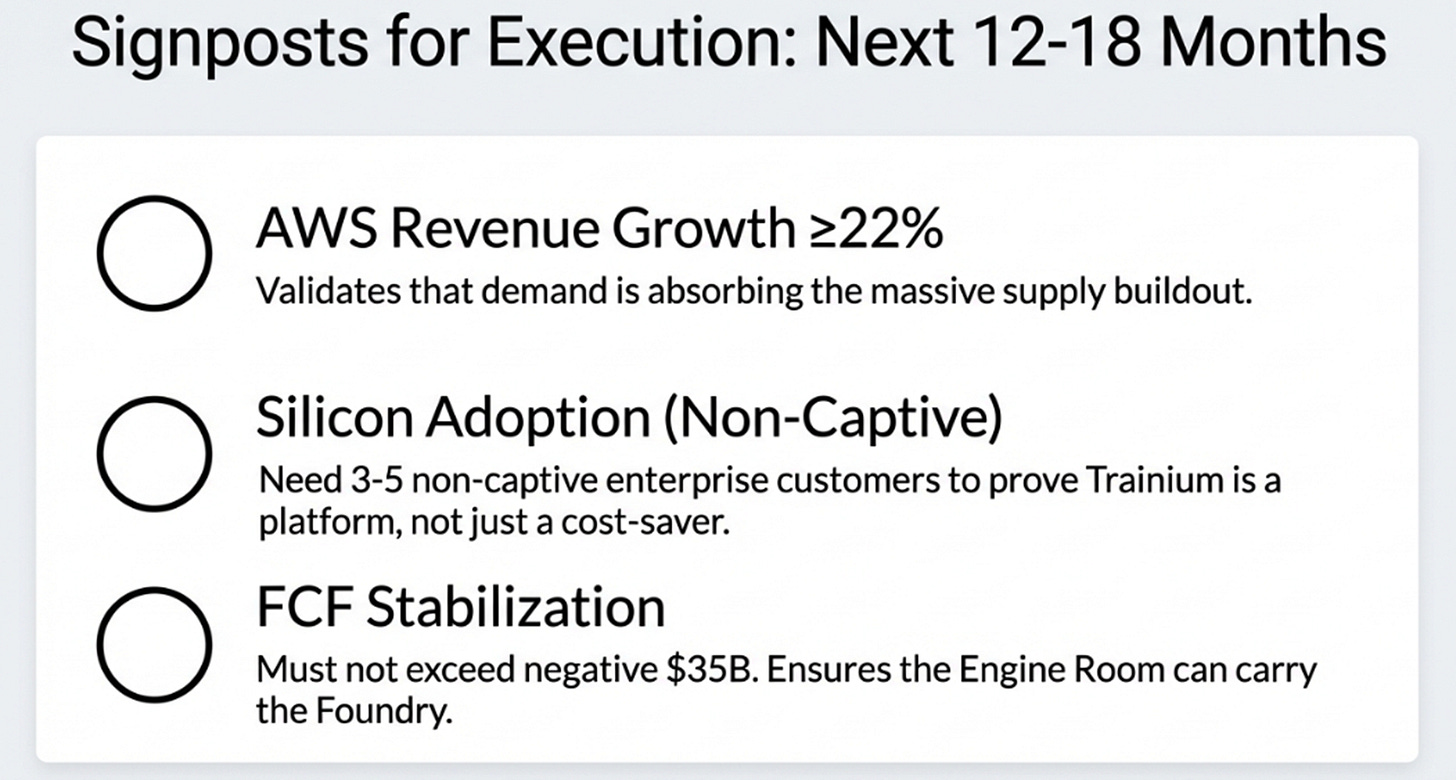

Three specific signposts will determine whether the thesis is working over the next twelve to eighteen months.

First, AWS revenue growth must hold at or above 22% as new capacity comes online through mid-2026. Growth at that rate on a $142 billion base would validate that utilization is high and demand is absorbing the supply buildout. A deceleration below 20% would suggest the opposite , that Amazon is building faster than the market can consume.

Second, Trainium must demonstrate adoption breadth beyond its current anchor tenants. The $10 billion run rate is impressive, but the silicon thesis only generates outsized returns if Trainium becomes a platform, not a captive chip. Look for three to five named enterprise commitments outside the current cohort by the second half of 2026.

Third, the consolidated free cash flow trajectory needs to stabilize rather than deteriorate. If FCF comes in worse than negative $35 billion for fiscal 2026, the balance sheet conversation shifts from “investment year” to “funding crisis,” and the Engine Room’s ability to carry the Foundry comes into genuine question.

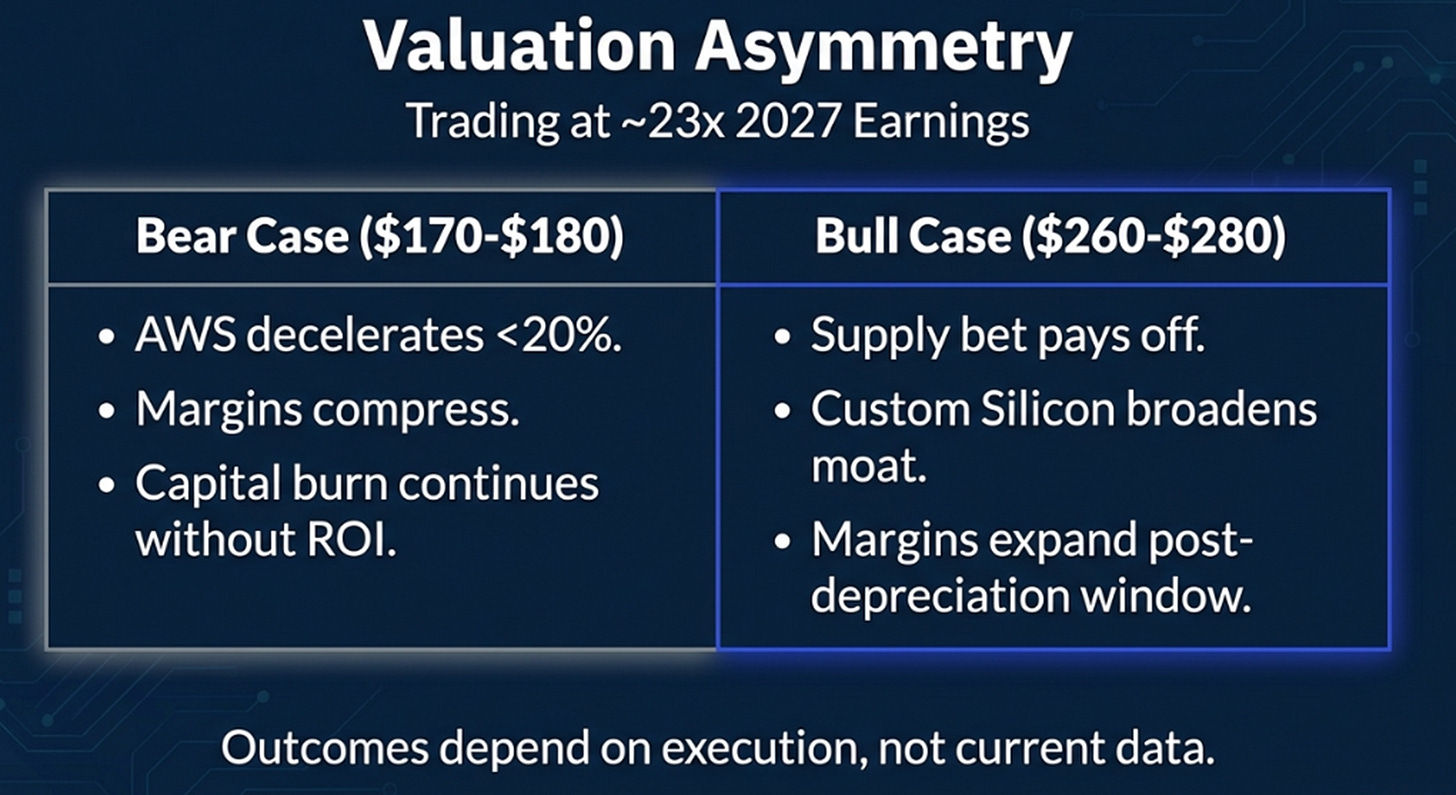

At approximately $210 per share, Amazon trades at roughly 23 times estimated 2027 earnings. That is not cheap for a company actively burning cash, but it is reasonable if the 2027–2028 earnings trajectory materializes. The asymmetry is real: perhaps $170–180 on the downside if AWS decelerates and margins compress, but $260–280 if the supply-side bet pays off and custom silicon broadens. The range is wide because the outcome genuinely depends on execution over the next two years, not on any information available today.

The Declaration

In that 2006 BusinessWeek story, Bezos said something that has become a kind of corporate proverb:

“We are willing to go down a bunch of dark passageways, and occasionally we find something that really works.”

AWS was the something. It turned a marginally profitable retailer into the most important infrastructure company in technology.

The $200 billion AI Foundry is the next passageway, darker and more expensive than anything that came before it.

Q4 2025 is not the quarter Amazon disappointed investors. It is the quarter Amazon declared what it is becoming. The Foundry is the company now. The Engine Room’s job, the retail habit loop, the advertising flywheel, the Prime subscription base, is to fund it. Every other capital decision, from quick commerce in India to Project Kuiper satellites to the 30,000 layoffs, is downstream of that priority.

Whether the bet pays off depends on variables that will not resolve in 2026. The stock will be volatile and likely range-bound as the market digests negative free cash flow and waits for proof that $200 billion converts into durable economics. But the structural position, diversified funding, vertical silicon integration, $244 billion in contracted demand, and a retail-and-advertising engine that generates both cash and data , is stronger than any competitor’s.

Twenty years ago, the market told Bezos to mind the store. He didn’t. The investors who understood why made forty times their money. Amazon is now asking investors to underwrite the same kind of patience, at the same kind of scale. The only difference is the number of zeros.

Disclaimer:

The content does not constitute any kind of investment or financial advice. Kindly reach out to your advisor for any investment-related advice. Please refer to the tab “Legal | Disclaimer” to read the complete disclaimer.