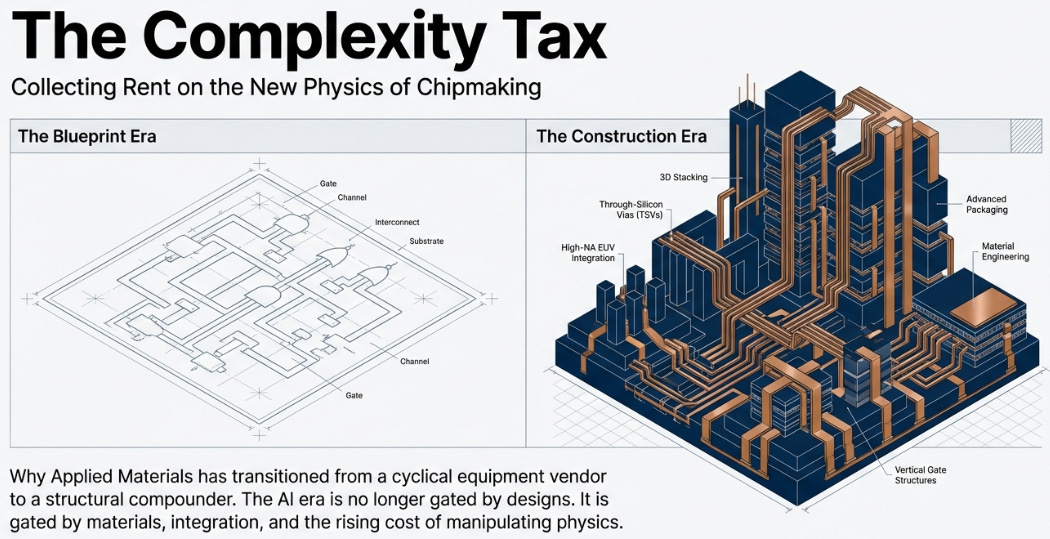

Applied Materials: When the Blueprint Stopped Being Enough

The AI era isn’t gated by designs anymore—it’s gated by materials, integration, and the rising “complexity tax” of manufacturing.

TL;DR

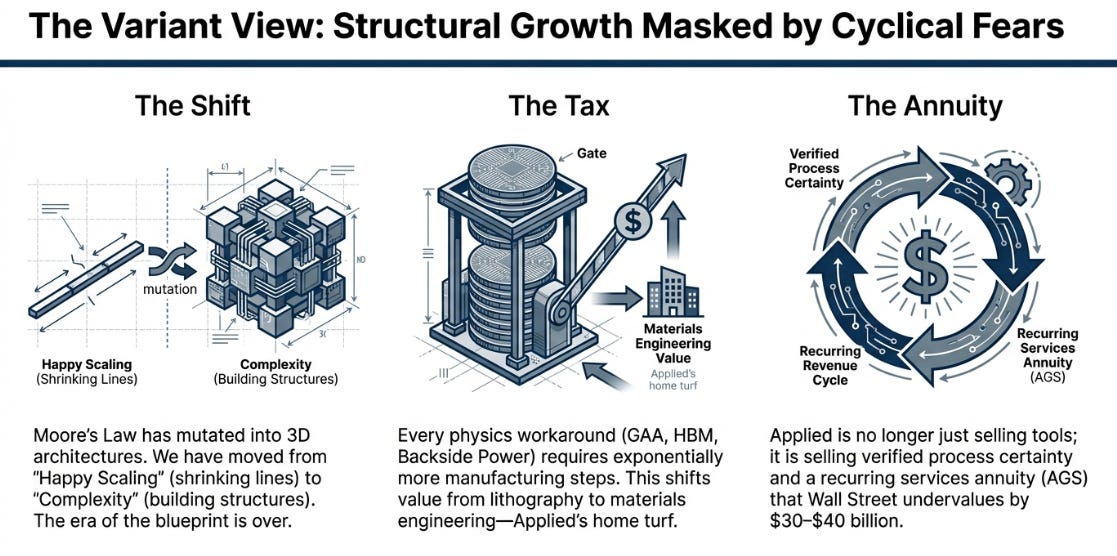

Moore’s Law didn’t die, it mutated into 3D architectures (GAA, HBM, backside power) that require far more deposition/etch/integration.

Every physics workaround adds a “complexity tax,” shifting value from lithography to materials engineering, Applied’s home turf.

Applied isn’t just selling tools anymore: it’s selling verified process certainty + a recurring services annuity Wall Street still undervalues.

The Age of Happy Scaling

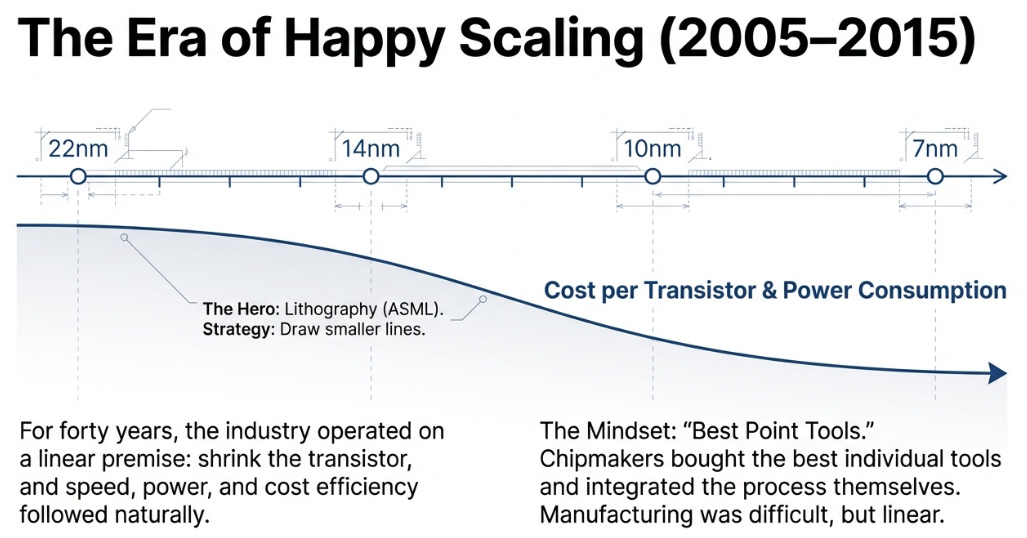

In 2005, Intel’s then-CEO Paul Otellini stood on stage and declared that Moore’s Law would continue for “at least another decade.” The confidence was understandable. For forty years, the semiconductor industry had operated under a simple, elegant premise: shrink the transistor, and everything else, speed, power efficiency, cost per function, followed naturally.

The hero of this story was the lithography machine. Each generation of ASML’s scanners could draw finer lines on silicon, and the entire industry, chipmakers, equipment suppliers, materials scientists, organized around this cadence. Applied Materials sold critical equipment for deposition, etching, and polishing, but the narrative belonged to lithography. If you could print smaller patterns, you could build better chips.

This was the era of two-dimensional scaling. The challenge was precision: could you draw a 22-nanometer line, then a 14-nanometer line, then a 7-nanometer line? The answer, for decades, was yes. Manufacturing was hard, but it was linear.

Then the physics stopped cooperating.

The Wall

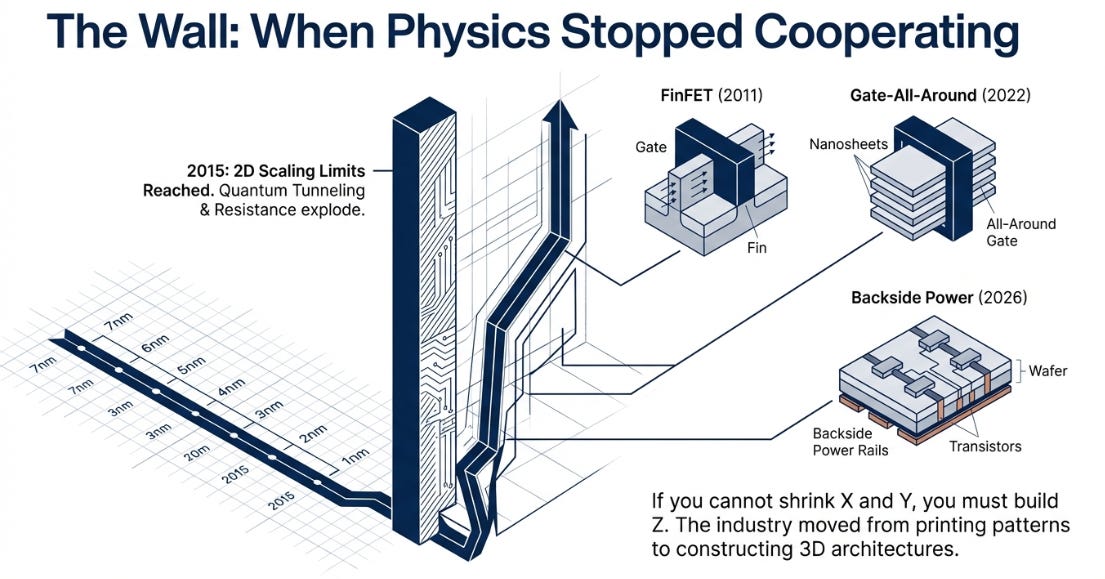

Around 2015, a problem emerged that lithography couldn’t solve. Transistors had become so small that quantum effects, electrons tunneling through barriers that should contain them, made the devices unreliable. Copper wires had shrunk so thin that electrical resistance exploded, causing chips to overheat. Two-dimensional scaling was hitting fundamental physical limits.

The industry’s response was radical: if you can’t shrink in two dimensions, build in three. FinFET transistors (2011) stacked the gate on three sides of the channel. Gate-All-Around transistors (2022 onward) wrapped it completely. High-Bandwidth Memory stacked DRAM chips vertically with microscopic through-silicon vias drilling through each layer. Backside power delivery (arriving 2026-27) flips the wafer over and builds an entirely separate power distribution network on the reverse side.

These weren’t just new designs. They were fundamentally different manufacturing problems. You couldn’t simply print these structures, you had to build them, atom by atom, with dozens of new deposition, etching, and integration steps that hadn’t existed before.

The bottleneck shifted. It was no longer about drawing finer lines. It was about constructing increasingly baroque three-dimensional architectures at atomic precision.

And suddenly, the most valuable company in the semiconductor equipment industry wasn’t the one with the best scanner. It was the one with the broadest toolkit for materials engineering.

The Complexity Tax

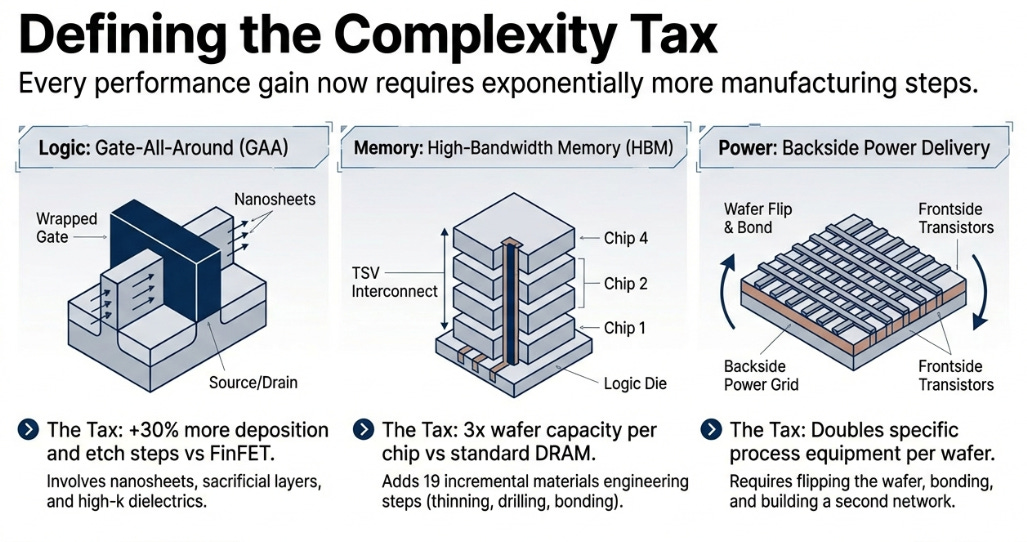

Every major technology transition in semiconductors since 2015 can be understood as a solution to a physics problem, and each solution carries what might be called a complexity tax.

Gate-All-Around transistors solve the leakage problem by wrapping the gate electrode around all four sides of the channel. The tax: Instead of a simple planar structure, you must deposit nanosheets, selectively etch sacrificial layers, deposit high-k dielectrics, deposit multiple work-function metals, and remove the sacrificial material without damaging anything else. GAA adds roughly 30% more deposition and etch steps versus the previous FinFET generation.

High-Bandwidth Memory solves the memory bandwidth bottleneck by stacking eight to twelve DRAM chips vertically and connecting them with through-silicon vias. The tax: Each chip must be thinned to 30 micrometers, you must drill holes through solid silicon, deposit barrier layers and fill the vias with copper, then bond the chips together with micron-level precision. HBM requires more than three times the wafer capacity per chip versus standard DRAM, and adds 19 incremental materials engineering steps that didn’t exist in conventional memory.

Backside power delivery solves the resistance problem by moving power distribution to the opposite side of the wafer, freeing the front side for signal routing. The tax: You must flip the wafer, deposit and etch an entirely new set of power rails using novel metals like ruthenium, create through-silicon vias to connect both sides, and develop new planarization techniques for dual-sided processing. This effectively doubles certain categories of process equipment per wafer.

The pattern is consistent: Every performance gain now requires exponentially more manufacturing complexity. And complexity, in this context, means materials engineering steps, the precise domain where Applied Materials competes.

Here’s what the market hasn’t fully internalized: This complexity is non-negotiable. If you want to build an AI chip that can train large language models, you need HBM. If you want a 2-nanometer processor, you need GAA. If you want to push beyond that, you need backside power. There is no Moore’s Law alternative anymore. You pay the complexity tax, or you don’t compete.

Applied Materials is the tax collector.

The Tollbooth

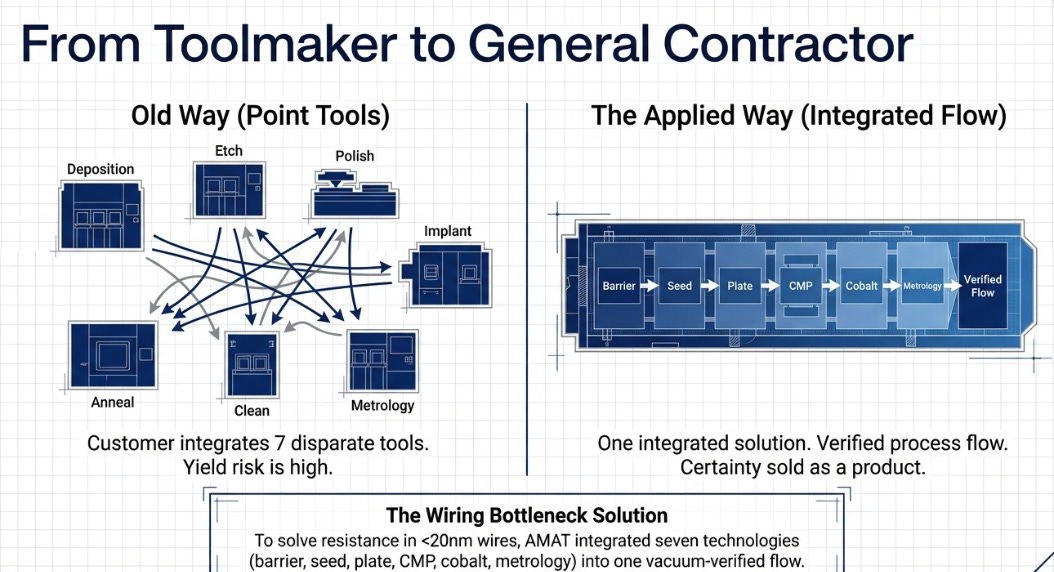

Applied’s competitive position can’t be understood through the old “best tool wins” framework. In the happy scaling era, chipmakers bought best-of-breed equipment for each step, etch from Lam Research, lithography from ASML, inspection from KLA, and integrated the process themselves.

But when a leading-edge fab runs 2,000+ process steps and a yield problem at step 1,200 might trace back to a 0.3-nanometer variance at step 150, integration becomes the bottleneck. You need process steps to work together, not just individually.

Applied’s response was to become what might be called the industry’s general contractor. Rather than selling individual tools, they began selling verified process flows, combining deposition, etch, and metrology within single vacuum-sealed chambers, or co-optimizing equipment across sequential steps.

A concrete example: The wiring bottleneck. As copper interconnects shrank below 20 nanometers, resistance spiked and reliability collapsed. Applied developed a solution that integrated seven different technologies, barrier deposition, copper seed layer deposition, electroplating, chemical-mechanical polishing, selective cobalt fill for the smallest wires, and real-time metrology, into a verified flow. Customers don’t buy seven tools and integrate them; they adopt Applied’s integrated solution, which delivers known-good results with faster time-to-yield.

This creates a different kind of moat. It’s much harder for a competitor to displace Applied when the customer is buying an end-to-end solution, not a point tool. The switching cost isn’t just requalifying one piece of equipment, it’s revalidating an entire process segment.

Applied is the only equipment company that can span deposition, etch, polishing, implant, and metrology within a single integrated offering. When GAA transistors or HBM integration require 15 different process technologies working in concert, breadth becomes the competitive advantage. Applied now has over 52,000 systems installed globally, an installed base that generates service revenue for 15-20 years per tool.

The market understands Applied sells equipment. What it undervalues is that Applied increasingly sells certainty, and in an era where time-to-market determines billions in revenue for chipmakers, certainty commands premium pricing.

The China Test Case

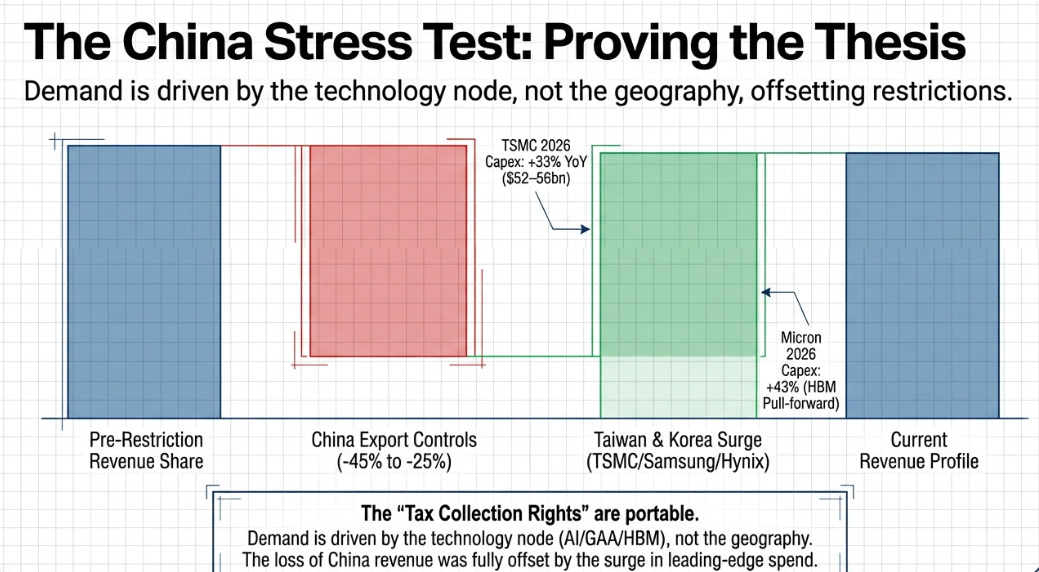

Export controls, imposed in waves since October 2022, forced Applied’s China revenue from 45% of total sales to 25%, a collapse of roughly $5 billion at peak. This looks catastrophic. It’s the primary bear case.

But the export controls did something unexpected: they proved the thesis. When China revenue fell from 45% to 25%, Taiwan and Korea’s combined share rose from 25% to 35%, in a single year.

The math is simple. Export controls eliminated roughly $600-700 million of Applied’s addressable China market in fiscal 2026. Meanwhile, TSMC’s 2026 capital expenditure increased 33% year-over-year to $52-56 billion. Applied captures roughly 19% of that incremental spend. TSMC alone represents $2-3 billion in new opportunity, four times the China headwind.

Add Micron (fiscal 2026 capex up 43%, with tools being pulled forward by four months due to HBM shortages) and SK Hynix (production ramped ahead of schedule), and the offset dwarfs the loss.

Why does the market overweight China risk? Headlines are asymmetric. “U.S. Restricts Chip Equipment to China” generates far more attention than “TSMC Raises Capex Guidance.” The former is a discrete, scary event; the latter is a boring operational update. But operationally, the Taiwan/Korea surge is three times larger.

The second-order effect matters too: China restrictions are pushing Applied’s revenue mix toward higher-margin, leading-edge tools. Chinese fabs were heavy buyers of mature-node equipment (lower prices, more competitive). Taiwan and Korea are buying GAA transistor tools and HBM packaging equipment, premium products with limited competition.

The geopolitical complexity tax is real. But the tax collection rights proved portable.

The Annuity No One Sees

Applied Materials operates what’s best understood as a two-engine business model, and the market systematically undervalues the second engine.

Engine One: Semiconductor Systems ($20.8 billion in fiscal 2025, 73% of revenue). This is the business everyone watches, capital equipment sales tied to new fab construction. It’s lumpy, cyclical, and headline-driven.

But here’s what’s underappreciated: because of the complexity tax, Semiconductor Systems revenue per wafer is rising even when wafer volumes are flat. When a fab transitions from FinFET to GAA, Applied’s equipment revenue per 100,000 wafer starts per month increases roughly 30%. When a memory maker converts standard DRAM capacity to HBM, Applied’s revenue per chip triples. Systems can grow 8-10% annually even if total wafer starts grow only 4-5%.

Engine Two: Applied Global Services ($6.4 billion in fiscal 2025, 23% of revenue). The market treats AGS as “services and spare parts”, a nice, stable business that cushions downturns. This radically understates what’s actually happening.

AGS is becoming a subscription business. Most AGS revenue now comes from long-term service agreements, contracts where customers pay Applied to maintain uptime, manage spare parts inventory, provide software upgrades, and optimize tool performance. These contracts run nearly three years on average with renewal rates exceeding 90%. This isn’t transactional repair revenue; it’s recurring revenue with enterprise software-like economics.

The flywheel works like this: Every tool Applied ships becomes part of that 52,000-system installed base. Each tool generates AGS revenue for 15-20 years. As complexity increases, service intensity rises, GAA transistor tools require more frequent maintenance, HBM packaging equipment needs tighter process control, and chipmakers increasingly buy long-term agreements because fab downtime costs millions per day.

AGS has grown for 21 consecutive quarters, including through the 2023 memory downturn when Semiconductor Systems revenue fell. AGS operating margins run near 30%, and the business is growing 8-10% annually regardless of equipment cycles.

Here’s what this means: Applied isn’t just selling capital equipment anymore. It’s building an installed base annuity that compounds in value as the base expands and service attach rates increase.

Starting in fiscal 2026, Applied will change its AGS reporting to make it a pure recurring-revenue segment. When investors see a ~$7 billion business growing double-digits with 30% operating margins and 90%+ retention, the market will likely re-rate this segment.

AGS is worth $80 billion as a standalone business. The market currently ascribes perhaps $40-50 billion of Applied’s $280 billion market cap to it. Someone’s wrong.

What the Market Is Missing

Wall Street agrees that AI is driving a multi-year equipment upcycle, that Applied is well-positioned in GAA and HBM, and that the company has strong competitive positions. The stock trades at 33x forward earnings, hardly unloved.

But the consensus misunderstands duration. Wall Street’s models show revenue growth accelerating through fiscal 2027, then flattening in 2028-2029. This is the traditional equipment cycle template: a few years of boom, then normalization or contraction.

Here’s what they’re missing: The complexity tax doesn’t cycle, it accumulates.

Gate-All-Around isn’t a one-time upgrade. It’s a new baseline. Every leading-edge fab going forward will be GAA, meaning every fab going forward will require 30% more materials engineering steps than its predecessor. HBM isn’t a niche product for a few AI accelerators, it’s becoming the standard memory architecture for datacenters. Backside power delivery will arrive in 2026-27, and it will be table stakes for 2-nanometer and below, adding another layer of equipment intensity.

These inflections don’t replace each other, they stack. A 2027-vintage fab will have GAA transistors, HBM packaging capability, backside power delivery, and advanced chiplet interconnects. Each adds equipment steps. The compounding effect means Applied’s revenue per wafer could be 50-60% higher in 2028 than it was in 2022, independent of whether wafer volumes themselves grow.

Wall Street is modeling a cyclical peak followed by mean reversion. The reality is more likely a structural step-change in Applied’s revenue base, followed by continued growth from that higher plateau.

The second element: AGS re-rating. Once the reporting change makes AGS’s recurring nature explicit, and once investors see 21+ consecutive quarters of growth with 30% margins, this segment will command a software-like multiple. The embedded re-rating is $30-40 billion.

Together, these two dynamics, underappreciated revenue duration and AGS re-rating, represent the variant. The market sees a cyclical company enjoying a strong upcycle. The reality is that Applied is transitioning into a secular compounder with a higher steady-state growth rate and a more durable earnings stream.

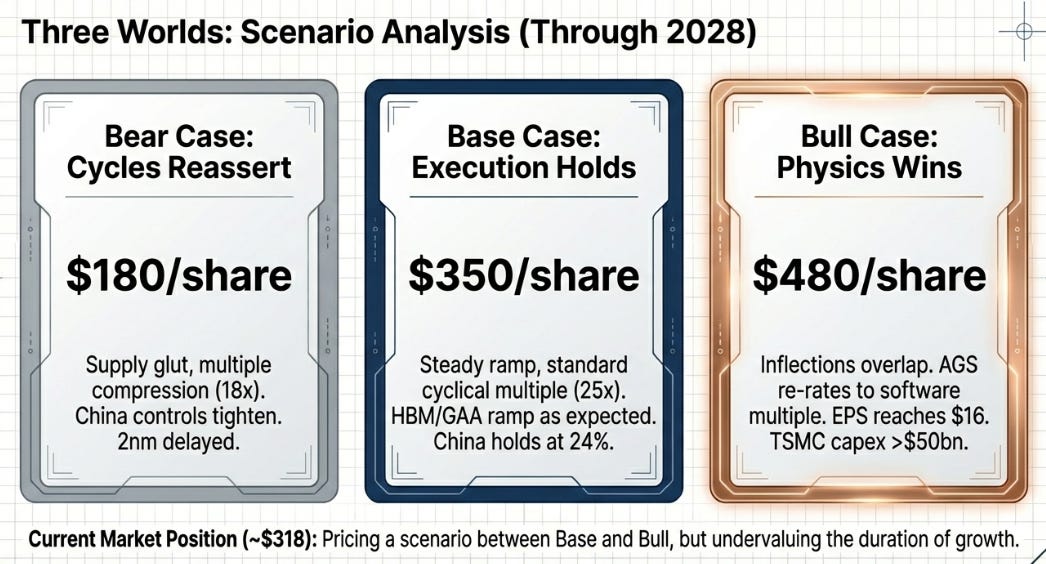

Three Worlds

At $318 per share, Applied Materials trades at a market capitalization of $282 billion with a forward P/E near 33x. Here are three paths for the stock over the next three years (through early 2028):

The World Where Physics Wins

All major inflections land on time and overlap. TSMC, Samsung, and Intel all ramp 2-nanometer GAA production through 2027. HBM capacity expansion continues through 2028 as memory makers chase AI datacenter demand that exceeds forecasts. Backside power delivery adoption accelerates, creating a second wave of equipment purchases in 2027-28. China revenue stabilizes at 26%.

Revenue grows 10-12% annually to $40 billion. Gross margins hit 50% as high-value integrated solutions become the dominant mix. AGS reaches 27% of total revenue. Operating margins rise to 33-34%. By fiscal 2028, EPS reaches $16.

At a 30x multiple, deserved if AGS gets re-rated as a subscription business, the stock trades around $480. That’s 50% higher than today, but it’s not heroic. It’s just the tax compounding.

This world requires TSMC capital expenditure staying above $50 billion through 2027, HBM TAM exceeding $110 billion by 2028, and Applied’s backlog remaining above $17 billion. The signals would be unmistakable: gross margin holding above 49%, AGS growing 10%+ regardless of what Systems does, and customers pulling tools forward rather than delaying them.

The World Where Execution Holds

AI demand is solid but lumpy. GAA ramps as expected but memory makers pause briefly in late 2026 due to inventory digestion. Backside power arrives on schedule but adoption is gradual. China holds at 24% of revenue. AGS grows steadily at 8-10% annually, providing ballast.

Revenue grows 7-8% annually to $35 billion. Gross margins stabilize at 48.5-49%. Operating margins reach 31-32%. Fiscal 2028 EPS hits $14.

The market maintains a 25x P/E, a premium to historical cyclical multiples, reflecting improved quality of earnings from AGS but not a full re-rating. The stock trades around $350, roughly 10% higher than today.

This world looks like steady execution without heroics. Annual WFE spending stays above $130 billion, TSMC capex stays above $48 billion, backlog remains above $15 billion, and gross margin doesn’t fall below 48%. It’s the “consensus-plus” scenario where everything works but without extraordinary outcomes.

The World Where Cycles Reassert

Memory oversupply develops by late 2026 as HBM capacity additions overshoot near-term demand. AI chip demand plateaus as hyperscalers pause datacenter expansion. TSMC and Samsung delay 2-nanometer high-volume manufacturing due to yield challenges. China export controls tighten further, dropping China to 18-20% of revenue.

Revenue grows only 1-2% annually to $30-31 billion. Gross margins compress to 46.5-47% as competitive pricing returns. Operating margins fall to 28-29%. Fiscal 2028 EPS drops to $9-10.

The market de-rates Applied to 18-20x P/E, the historical trough multiple for cyclical equipment companies. The stock falls to $180, down 43% from today.

This world breaks when DRAM spot pricing falls more than 10% quarter-over-quarter, TSMC cuts 2027 capex below $45 billion, backlog falls below $14 billion, and gross margin drops below 47.5% for two consecutive quarters. The bear case isn’t Applied becoming a bad company, it’s Applied being repriced as a cyclical that got ahead of itself.

The Question That Matters

Return to the story that opened this piece. In the happy scaling era, chipmakers won by printing smaller lines. The hero was lithography, and equipment suppliers were supporting actors.

That era ended around 2015, not because lithography failed, but because physics intervened. You can’t shrink a transistor below a certain size without it leaking. You can’t thin a wire indefinitely without resistance exploding. The solution was to build in three dimensions, to use exotic materials, to engineer at the atomic level.

The bottleneck moved from the blueprint to the construction, and the construction phase is vastly more complex. Gate-All-Around requires 30% more materials engineering steps. High-Bandwidth Memory requires three times the wafer capacity per chip. Backside power delivery adds an entirely new dimension to manufacturing. These aren’t one-time upgrades. They’re the new baseline.

Applied Materials has spent the last decade positioning itself as the general contractor for this new era, not just supplying individual tools, but delivering integrated solutions that combine deposition, etch, planarization, and metrology into verified process flows. The moat isn’t “best etcher” anymore. It’s breadth plus integration capability.

Wall Street understands the near-term story: AI is driving equipment demand, and Applied is benefiting. What the market is mispricing is duration. The consensus sees a strong 2025-2027, then expects reversion. The reality is that the complexity tax doesn’t cycle, it accumulates. Every fab going forward will be more equipment-intensive than the last.

Meanwhile, Applied Global Services, the maintenance contract business that Wall Street treats as a cushion, is quietly becoming a subscription annuity with software-like economics. Twenty-one consecutive quarters of growth, 90%+ renewal rates, 30% operating margins, and an installed base that grows every time Semiconductor Systems ships a tool.

You’ll know the thesis is working when backlog stays above $16 billion, gross margin holds at 48.5%+, and AGS keeps growing regardless of what Semiconductor Systems does. You’ll know it’s breaking when TSMC swaps “expand” for “optimize” in capex commentary, or when DRAM pricing collapses 10% in a quarter, or when gross margin falls below 47.5% for two quarters running. The signals aren’t subtle.

At $318 per share and 33x forward earnings, the market is already ascribing a premium multiple.

If this is a cycle, the stock reverts to 20x and trades at $220-250 as investors wait for the inevitable downturn. If this is physics, if the complexity tax is permanent and AGS deserves a software multiple, the stock compounds to $350-480 as revenue grows 7-12% annually for the next decade. The market is pricing something in between.

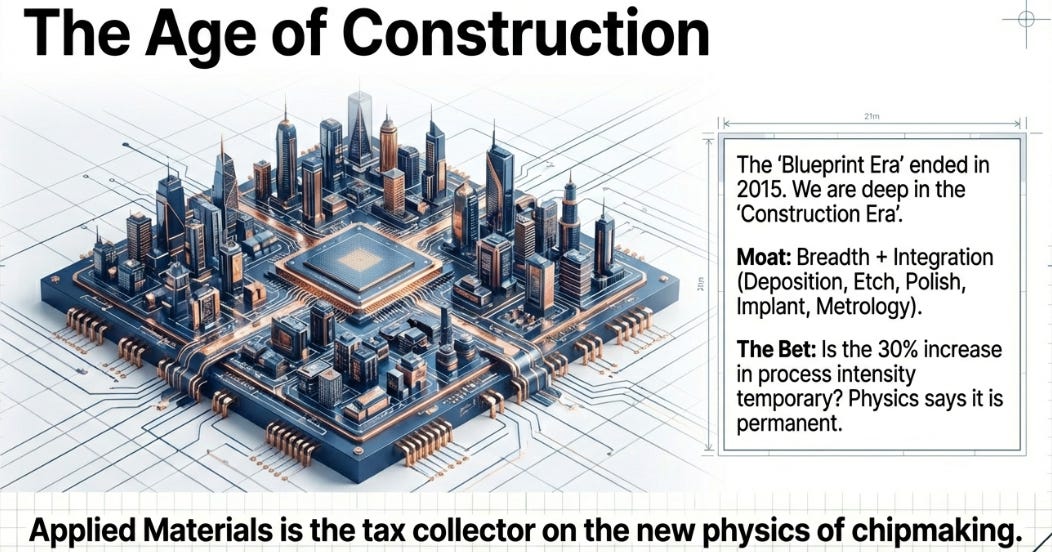

The variant bet is simple: The age of the blueprint is over. We’re in the age of construction. And construction, when it involves building structures atom by atom at scales invisible to any microscope, requires a complexity tax that isn’t going away.

Applied Materials isn’t just selling equipment for the AI boom. It’s collecting rent on the new physics of chipmaking.

The real question isn’t about the multiple. It’s about whether a 30% increase in process steps per wafer, already happening, already measured, already being paid for by TSMC and Samsung, represents a permanent change in how chips get made, or a temporary spike that will revert.

The toolmakers of the happy scaling era would smile at the irony. Sixty years after the integrated circuit was invented, the machinery isn’t just critical, it’s become the advantage itself.

Disclaimer:

The content does not constitute any kind of investment or financial advice. Kindly reach out to your advisor for any investment-related advice. Please refer to the tab “Legal | Disclaimer” to read the complete disclaimer.

This article came at the perfect time. Your clear explanation of Moore's Law mutating into 3D architectures and the "complexity tax" really resonated. Physics constantly challenges us, so what do you see as the next big material science frontier for chip development? Realy insightful, thanks for this smart perspective.

Fantastic breakdown of how the semiconductor value chain is reshaping. That "complexity tax" framing is spot-on becuase it clarifies why AMAT's moat is actually widening even as WFE growth moderates. The AGS annuity angle is underappreciated too... most folks still treat servicing as a nice side business when it's basically turning into a SaaS model with 90% renewal rates. I hadn't conected how export controls paradoxically upgraded their revenue mix toward premium tools, clever observation.