ARM's 2QFY26 Earnings: The Paradox of Power and Neutrality

How a 1997 decision not to compete built a trillion-dollar ecosystem—and now tests the limits of trust in the age of AI silicon.

TL;DR

Neutrality as strategy: Robin Saxby’s 1997 vow that ARM would never compete with its customers created a platform trusted by every major chipmaker—and that trust became its most valuable asset.

Power at peak: Q2 FY26 results show record growth driven by Compute Subsystems (CSS) and Neoverse data center traction—but also reveal rising operational complexity that strains ARM’s “pure IP” identity.

Crisis of temptation: SoftBank’s ambitions to vertically integrate risk shattering ARM’s covenant of neutrality—potentially triggering an ecosystem shift toward RISC-V and eroding the trust premium that built its empire.

The 1997 Decision That Built a Kingdom

In 1997, ARM Holdings faced bankruptcy. The British chip design company had developed an elegant, power-efficient processor architecture, but revenues were collapsing. The board faced a choice: should ARM build and sell its own chips, or license its designs to others?

Robin Saxby, ARM’s CEO, made a decision that would define the company for decades: “We will never compete with our customers.” ARM would be a pure licensor, providing intellectual property to chipmakers while staying out of manufacturing and chip sales entirely. This wasn’t obvious. It meant leaving enormous value on the table—ARM would enable a trillion-dollar ecosystem while capturing only a fraction of it.

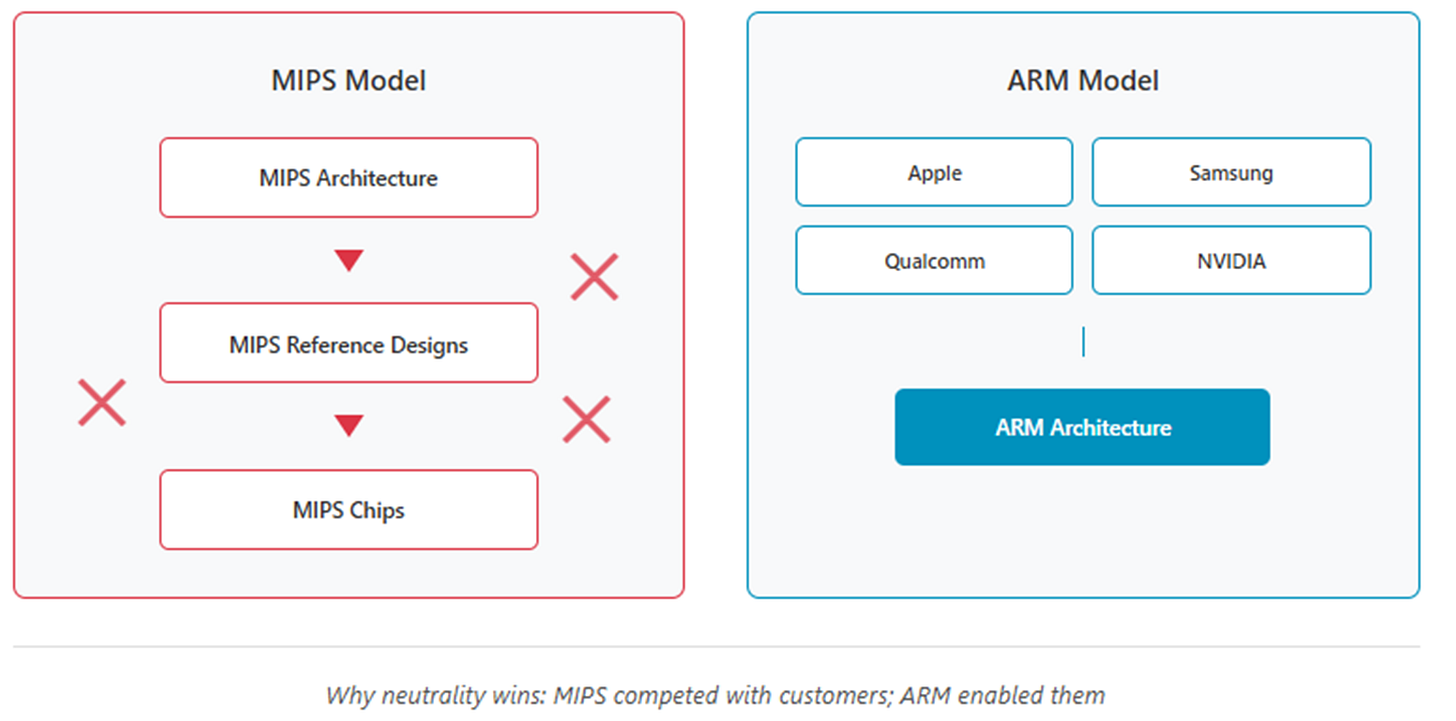

The counterexample was everywhere. MIPS Technologies had superior technology in many respects, but it tried to capture value at multiple layers—licensing its architecture while also building reference designs that competed with licensees. The ecosystem fragmented. Partners never quite trusted MIPS. When competitive pressure came, MIPS’s customers had already hedged with alternatives.

ARM’s neutrality became its superpower. Apple could build custom processors without fearing ARM would compete with the iPhone. Samsung could invest billions in Exynos chips knowing ARM wouldn’t launch a rival product. Qualcomm could dominate Android with Snapdragon because ARM was a foundation, not a competitor. Every major technology company could build on ARM simultaneously, without the prisoner’s dilemma of funding a competitor’s ecosystem.

Twenty-eight years later, that covenant is being tested.

The Architecture of Influence

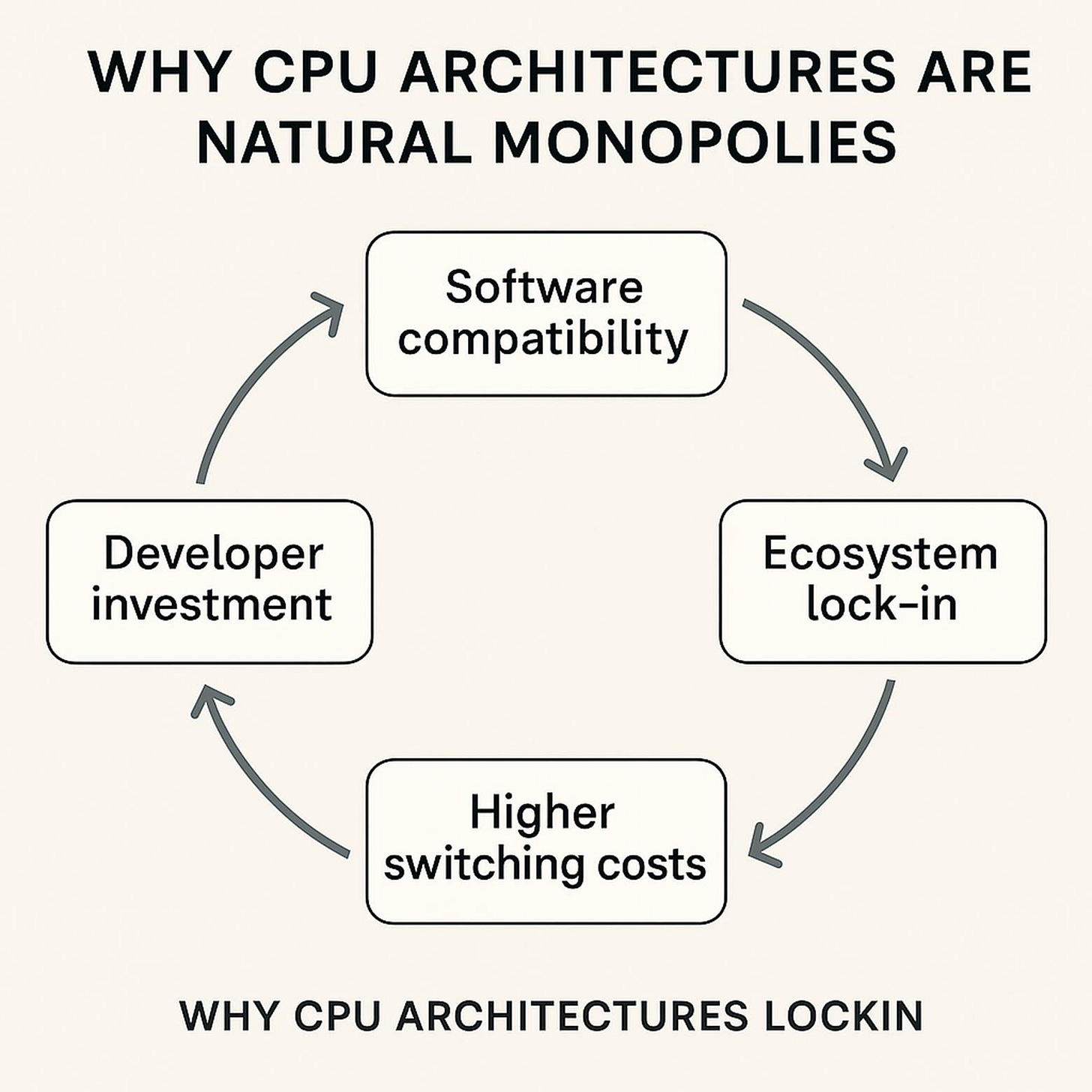

To understand what’s at stake, you need to understand why CPU architectures are natural monopolies—and why neutrality determines which monopoly wins.

Software compatibility creates exponential switching costs. Once an architecture embeds itself in an ecosystem, replacement becomes almost impossible. Every application, every driver, every optimization, every security certification represents engineering hours that would need recreation. Developer time is the most expensive resource in technology. Apple spent an estimated $2 billion transitioning Macs from x86 to ARM, and Apple controls both the hardware and operating system. For the broader ecosystem, switching costs are measured in tens of billions.

This is why architectures, once established, become infrastructure—invisible but essential, like electrical standards or Internet protocols. The value isn’t in the technical specifications; it’s in the accumulated investment built on top of them.

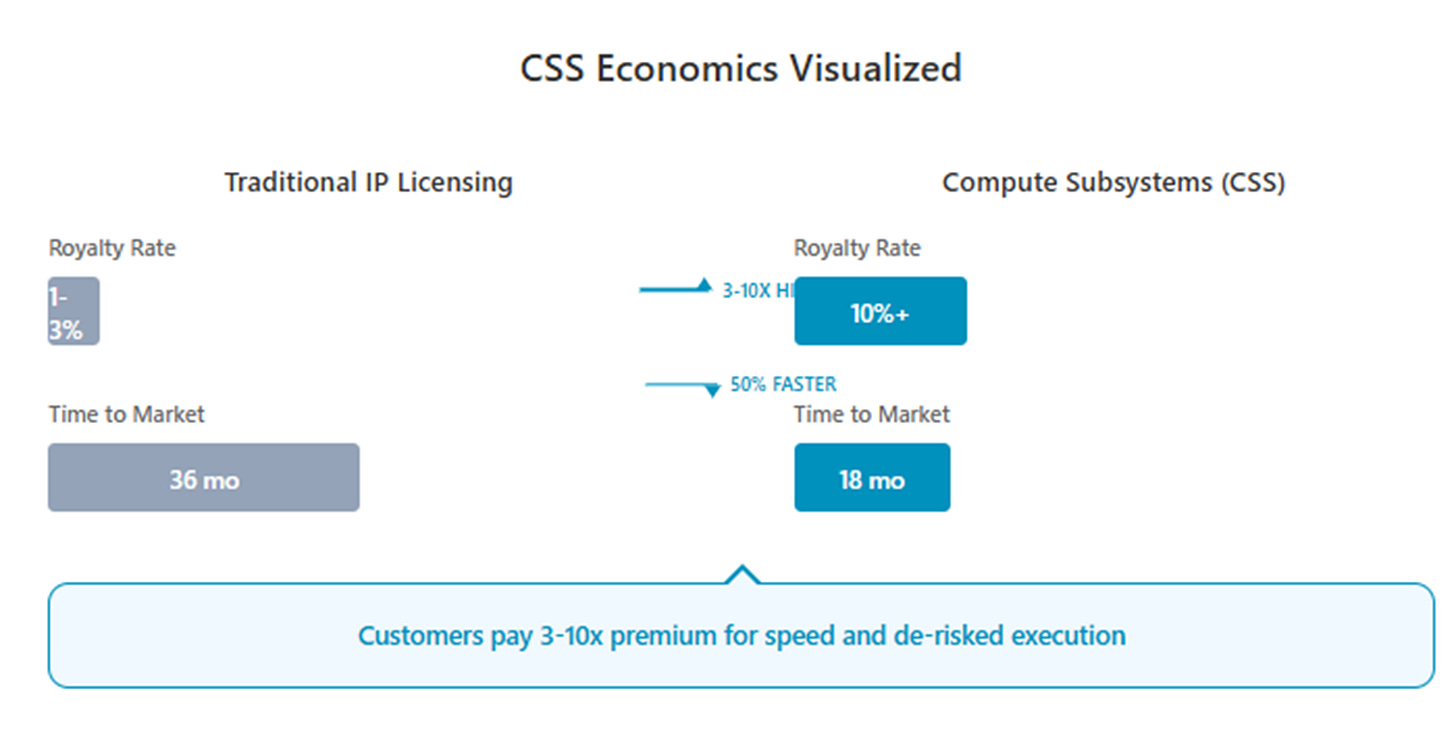

But here’s the critical insight: ecosystems consolidate around trusted platforms, not just technically superior ones. ARM’s value to customers isn’t that it’s technically better than x86 or RISC-V (though power efficiency matters). ARM’s value is that customers trust ARM won’t compete with them. This trust has economic value. ARM disclosed this quarter that CSS (Compute Subsystems) command royalty rates “exceeding 10% of chip ASP” versus 1-3% for standard IP licenses. That 3-10x premium is customers paying for infrastructure they trust.

Platform owners always face the temptation to move up the stack. There’s vastly more value in chips ($240 billion market) than in architecture licensing ($5-7 billion). ARM enables an ecosystem worth 50x its own revenue. From a pure economic perspective, capturing more of that value is rational.

The pattern is consistent across technology platforms. Microsoft tried to force Windows Phone onto the ecosystem while licensing Windows Mobile. Partners fled to Android. Google maintains Android as open-source to prevent carriers and OEMs from viewing it as competitive. Apple keeps iOS proprietary but doesn’t license it—you can’t be neutral if you also compete.

Every platform that broke neutrality triggered competitor emergence—not because the alternative was better, but because ecosystem participants needed insurance against a platform that might prioritize its own interests.

Q2 FYE26: Three Signals in the Data

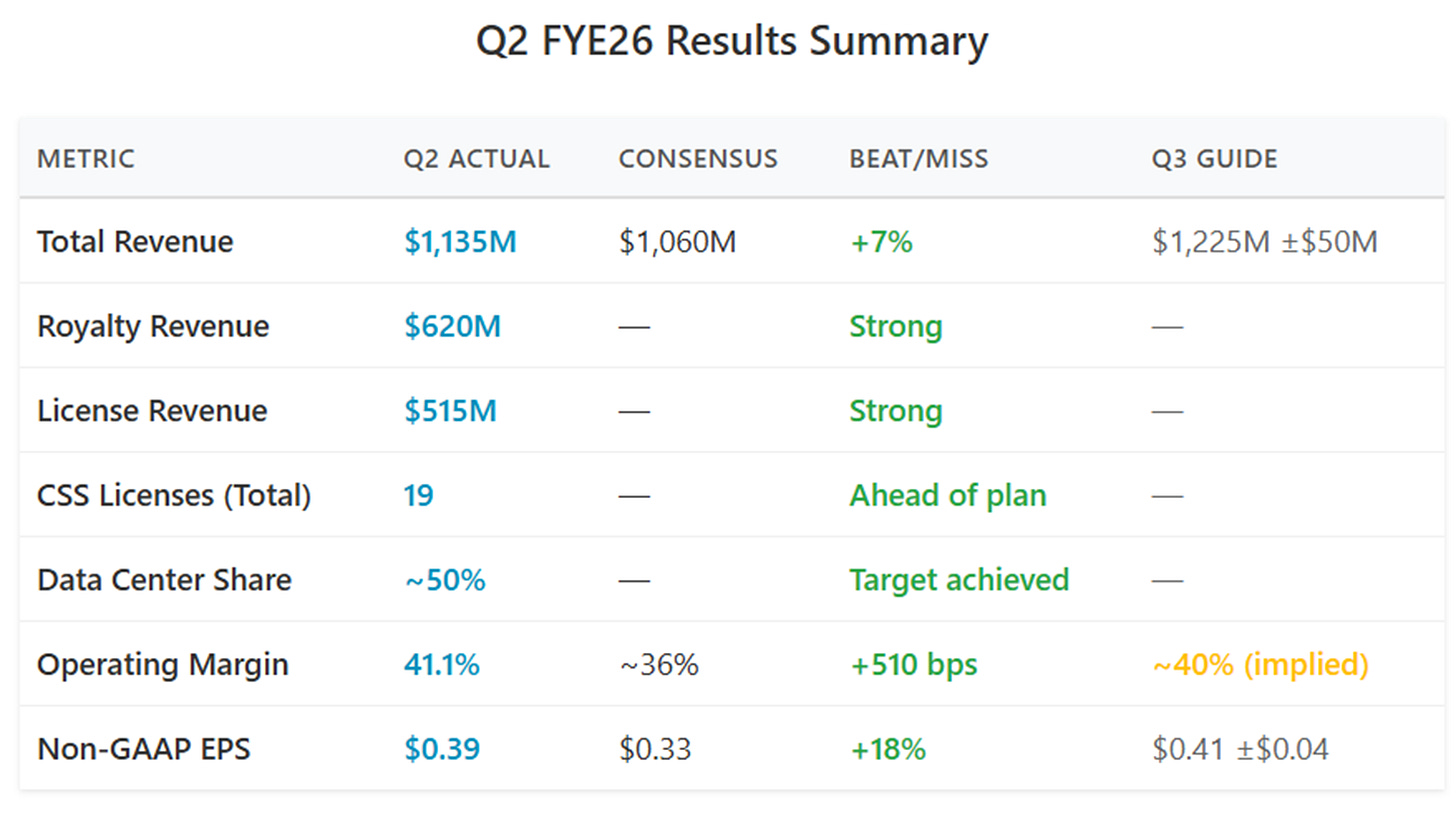

ARM’s Q2 results—$1.14 billion revenue (+34% YoY), $620 million royalty (+21%), 19 CSS licenses, and approaching 50% hyperscaler CPU share—demonstrate the platform at peak power. But three signals reveal the underlying dynamics.

Before examining those signals, understanding Compute Subsystems is essential. CSS is ARM’s pre-integrated package of CPU cores, GPU, system IP, and interconnect fabric—essentially a substantial portion of a system-on-chip delivered as a validated, ready-to-integrate design. Instead of licensing individual IP blocks and spending 2-3 years integrating them, customers license CSS and can reach production silicon in 12-18 months.

This matters because chip design complexity has exploded. Modern smartphone processors have 10+ billion transistors across dozens of IP blocks that must work together flawlessly. CSS shifts integration burden from customer to ARM. The customer still differentiates through additional IP, manufacturing node choices, and system design—but the foundation is pre-validated.

The business model implication: CSS commands 10%+ royalty rates versus 1-3% for traditional IP licensing because customers are buying speed, de-risked execution, and ARM’s integration expertise—not just architecture rights.

Signal 1: The CSS Validation. One customer is already shipping second-generation CSS, likely Samsung based on timing and volume. Going from license to shipping silicon in 18 months versus the traditional 36-month cycle isn’t just efficiency—it’s a different business model. The standard-bearer now accelerates ecosystem building, reducing execution risk that historically limited custom silicon to the largest players.

But notice what ARM didn’t disclose: the Gen-2 royalty rate. If it increased meaningfully—proving customers willingly pay more for proven infrastructure—ARM would have said so. The omission suggests rates stayed flat, perhaps 10-12%. This is ARM testing how much value it can capture while maintaining neutrality. The public disclosure of “exceeding 10%” was strategic signaling—to investors (proving pricing power) and to customers (anchoring expectations).

Signal 2: Data Center as Second Foundation. Neoverse royalties doubling isn’t about ARM “beating” x86. It’s about structural economics. When NVIDIA’s Grace Blackwell systems demonstrate 25x better power efficiency for AI workloads, the architectural choice becomes economically deterministic. Meta’s commitment completed the set: AWS Graviton, Google Axion, Microsoft Cobalt. ARM achieved total coverage of the cloud computing oligopoly.

But here’s what matters: there are no more elephants to hunt. Every major hyperscaler has committed. Future growth comes from TAM expansion (hyperscalers building more data centers) not market share gains. Neoverse doubling reflects infrastructure expansion, not x86 replacement. Growth is now tied to AI capex cycles, not architectural displacement.

Signal 3: The OpEx Surge. Operating expenses jumped from $648 million to $720 million (Q3 guidance), growing 31% while revenue grew 34%. Platform businesses show operating leverage—incremental customers cost less to serve. Services businesses don’t—each customer requires dedicated resources.

The OpEx surge reveals what CSS actually is: not a standardized platform product, but semi-custom design services. Each CSS customer appears to need meaningful ARM engineering engagement. This is fine—it’s still high-margin, valuable work. But it means terminal operating margins are probably 44-46%, not the 50-55% that pure platform economics would deliver.

What the data reveals: ARM is successfully capturing more value through CSS and Armv9 adoption, but at the cost of increased complexity and resource intensity. Operationally, this is strong execution. Strategically, it’s testing the limits of neutrality.

The SoftBank Question: When the Kingmaker Wants the Crown

The SoftBank-Marvell acquisition rumors matter not because acquisition is certain, but because they reveal the strategic tension that will define ARM’s next decade.

The Stargate partnership provides context. At an estimated $700 million+ annual run-rate, SoftBank is funding what amounts to “off-balance-sheet R&D”—paying ARM to build next-generation technology that ARM will own. For a public company, this is an enormous advantage, allowing investment in future platforms without quarterly earnings pressure.

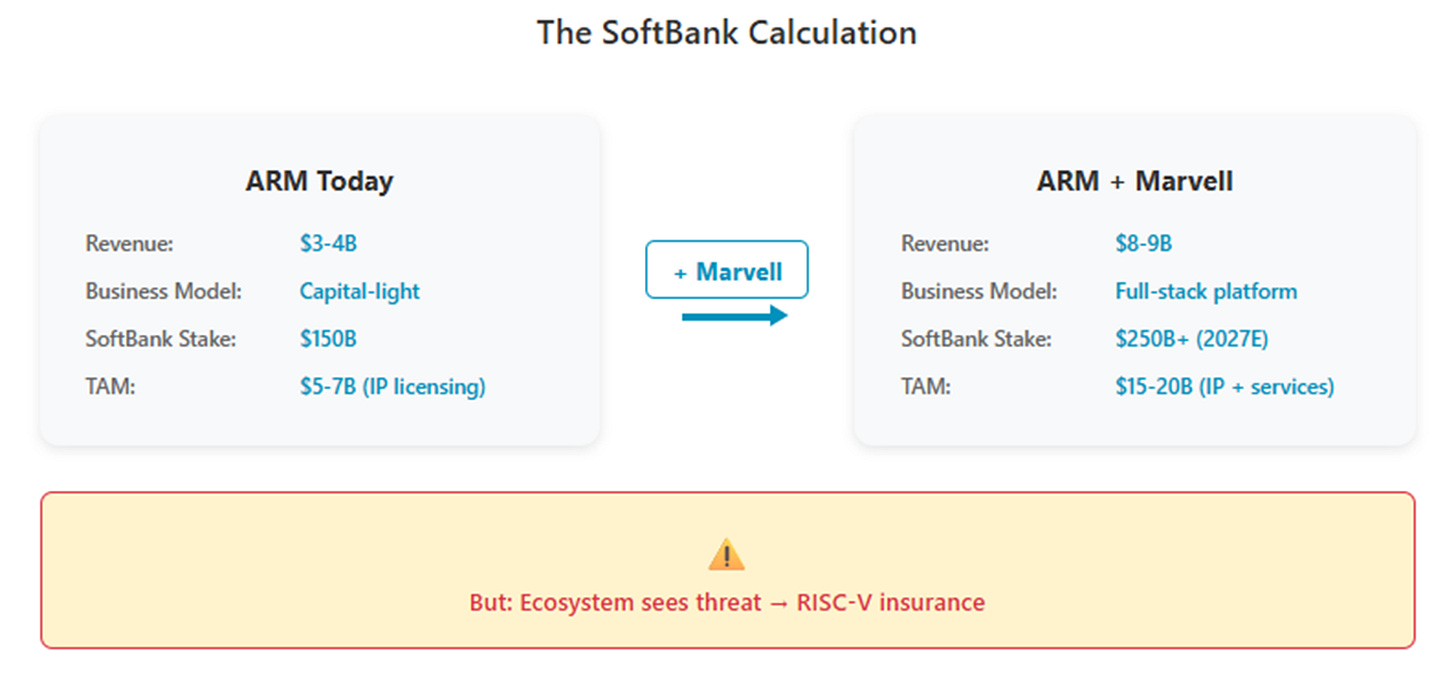

But the Marvell rumors reveal the other side of this relationship. Masa Son’s logic is straightforward: ARM enables a $240 billion chip ecosystem but captures $3-4 billion. Adjacent to this sits a $15-20 billion design services market—companies like Marvell, Synopsys implementation services, independent ASIC houses that help customers build chips. Why not capture both layers?

ARM + Marvell would create a full-stack platform: ARM provides IP architecture, Marvell provides physical design and implementation, the combined entity coordinates TSMC manufacturing. The pitch is compelling: “You want custom AI silicon but lack internal capability? We’ll deliver working chips in 18 months.” It’s “AWS for custom silicon”—infrastructure as a service.

From SoftBank’s capital deployment perspective, this is elegant. ARM alone is capital-light, can’t absorb investment at SoftBank’s scale. Adding design services creates a $8-9 billion revenue business that justifies deploying $2-3 billion in growth capital. SoftBank’s stake appreciates from $150 billion to $250 billion+ over 3-4 years.

Here’s the fatal flaw. SoftBank is thinking like an investor—ROI, TAM expansion, absolute returns. They should be thinking like a constitutional designer—long-term stability, ecosystem health, trust preservation.

The pattern is clear. Microsoft spent years forcing Windows Phone onto mobile carriers while licensing Windows Mobile to them. Partners fled to Android. Oracle’s aggressive enterprise software acquisitions—buying competitors to lock in customers—triggered the rise of open-source alternatives. Intel’s Atom processors competed with ARM licensees in mobile; Intel lost mobile entirely.

The common thread: when the standard-setter competes with the ecosystem, neutrality evaporates. Even if ARM claims it’s “only serving customers who can’t design their own,” Apple sees existential threat. So does NVIDIA. So does Qualcomm. They don’t need to believe ARM will cut them off—they just need to believe ARM might prioritize its own designs in future architecture decisions, or offer preferential CSS pricing, or use ecosystem data competitively.

At that point, funding RISC-V isn’t about technical superiority. It’s insurance. And these companies can make RISC-V viable much faster than organic timelines suggest.

The Three Paths Forward

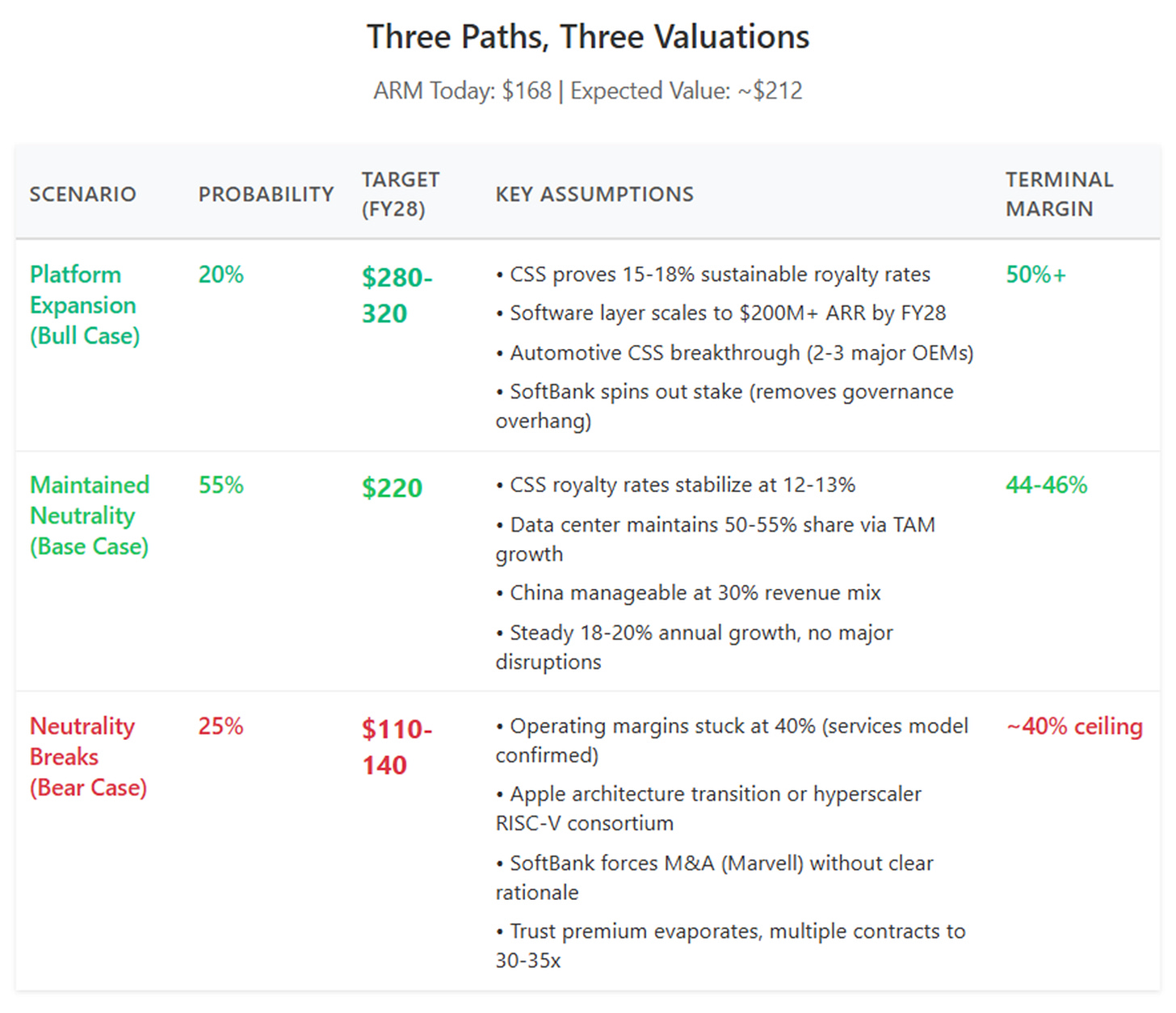

Path 1: Maintained Neutrality (Base Case, 55% probability). CSS remains an option for customers who value time-to-market, not a mandatory gateway. Software tools strengthen the ecosystem without becoming extraction mechanisms. Operating margins reach 44-46% as CSS scales. The business grows 18-20% annually. Stock worth approximately $220 by FY28—a strong outcome reflecting defensible position, but not transformative.

Path 2: Successful Platform Expansion (Bull Case, 20% probability). ARM threads the needle—expanding into software monetization and chiplet designs while maintaining trust through structural commitments. Automotive CSS creates a third revenue engine. SoftBank provides capital without demanding strategic control, or announces stake reduction. Margins reach 50%+. Stock worth $280-320.

Path 3: Neutrality Breaks (Bear Case, 25% probability). SoftBank forces Marvell combination or similar vertical move. Major customers accelerate RISC-V investment from token ($10-20 million annually) to strategic ($200-300 million annually). Technical switching costs remain high, but insurance value justifies investment. ARM remains good business but loses the trust premium. Multiple contracts to 30-35x. Stock worth $110-140.

The damage would be invisible at first. Companies wouldn’t immediately stop licensing ARM. They’d quietly fund alternatives. By the time ARM noticed declining ecosystem investment, competitive position would have degraded significantly.

What to Watch

Three indicators matter more than quarterly metrics:

· First, does ARM introduce mandatory CSS features? If future architecture extensions or security features are only available through CSS rather than traditional licensing, ARM is testing leverage limits. It would signal a shift from “CSS as option” to “CSS as gateway.”

· Second, watch customer behavior, not statements. Hyperscalers expanding internal chip design teams, increasing RISC-V foundation engagement, funding RISC-V tool development—these actions reveal trust dynamics better than diplomatic press releases.

· Third, SoftBank’s language. If Masa Son speaks about “strategic combinations” or “vertical integration” or “capturing more value,” the direction is clear. Son has never been subtle about ambition.

The ultimate prediction is behavioral: over the next 18 months, ARM’s strategic health won’t be measured by revenue growth or margin expansion. It will be measured by whether hyperscalers increase RISC-V investment from token to strategic—from $10-20 million annually to $200-300 million. That shift would happen before any Marvell announcement, as insurance against what customers see coming.

ARM’s Q2 validated the standard’s power. Data center inflection is real, CSS is working, platform transformation is executing. The question isn’t whether the architecture is technically superior—it is. The question is whether ARM remembers why standards win: not by exercising maximum control, but by enabling maximum ecosystem value.

The company Robin Saxby built succeeded because it rejected power in favor of influence. The question is whether the company Masa owns will make the same choice.

Disclaimer:

The content does not constitute any kind of investment or financial advice. Kindly reach out to your advisor for any investment-related advice. Please refer to the tab “Legal | Disclaimer” to read the complete disclaimer.