Broadcom 4QFY25 Earnings: The Discipline Discount

The market punished Broadcom for telling the truth. That tells you everything about AI investing right now.

TL;DR:

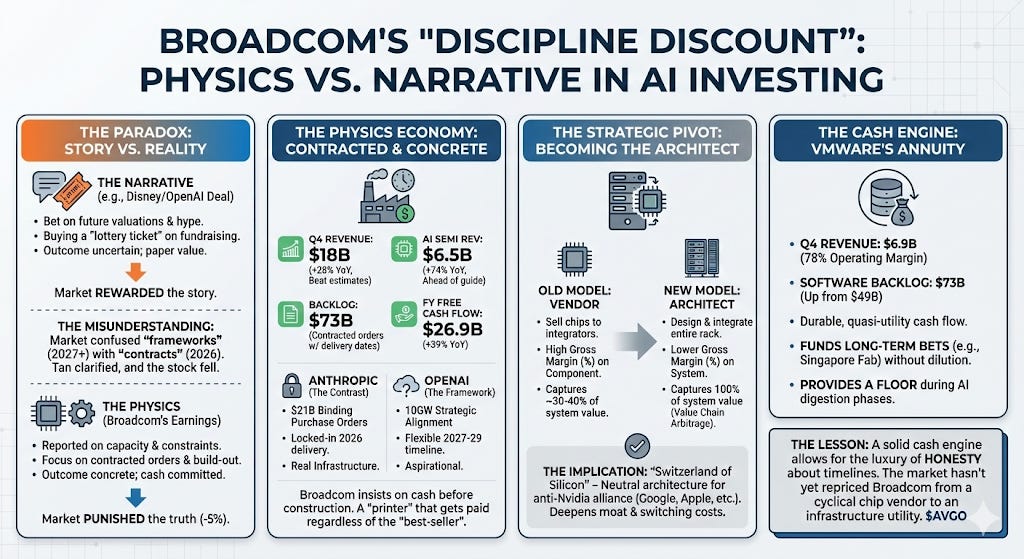

Disney bought narrative optionality (warrants on OpenAI’s next valuation); Broadcom sells physics (contracted backlog, delivery dates, capacity constraints)—and the market still priced them backwards.

The stock dropped because investors treated the OpenAI “10GW” headline like 2026 revenue; Tan clarified it’s 2027–2029 alignment, not binding purchase orders.

The bigger signal: Broadcom is evolving from chip vendor to end-to-end AI rack architect—lower margin %, bigger profit dollars, and deeper multi-generation lock-in (funded by VMware cash flow).

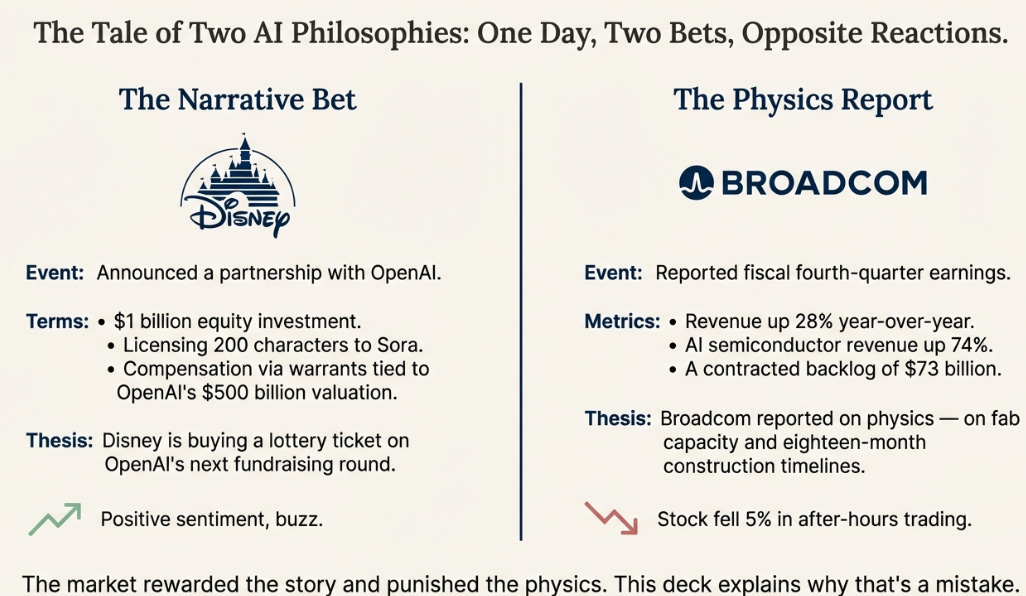

On Thursday morning, Disney announced a partnership with OpenAI. The details were revealing: Disney would invest $1 billion in equity, license 200 characters to OpenAI’s Sora video generation app, and receive compensation via warrants tied to OpenAI’s current $500 billion valuation. Read the structure carefully. Disney isn’t buying a stake in OpenAI’s business. Disney isn’t paying for access to technology. Disney is buying a lottery ticket on OpenAI’s next fundraising round. If OpenAI raises at $750 billion, the warrants appreciate. If AI sentiment cools and the valuation drops, Disney holds worthless paper.

On Thursday afternoon, Broadcom reported fiscal fourth quarter earnings. Revenue up 28% year-over-year. AI semiconductor revenue up 74%. A backlog of $73 billion in contracted orders with specified delivery dates. Cash committed before capacity built. The stock promptly fell 5% in after-hours trading.

Same day. Same AI boom. Opposite philosophies.

Disney made a bet on stories — on valuations rising, on narratives compounding, on the greater fool arriving before the music stops. Broadcom reported on physics — on fab capacity and packaging constraints and eighteen-month construction timelines. The market rewarded the story and punished the physics.

This is the central confusion of AI investing in 2025, and Broadcom’s earnings made it impossible to ignore.

The Paradox

The numbers themselves were exceptional by any reasonable standard.

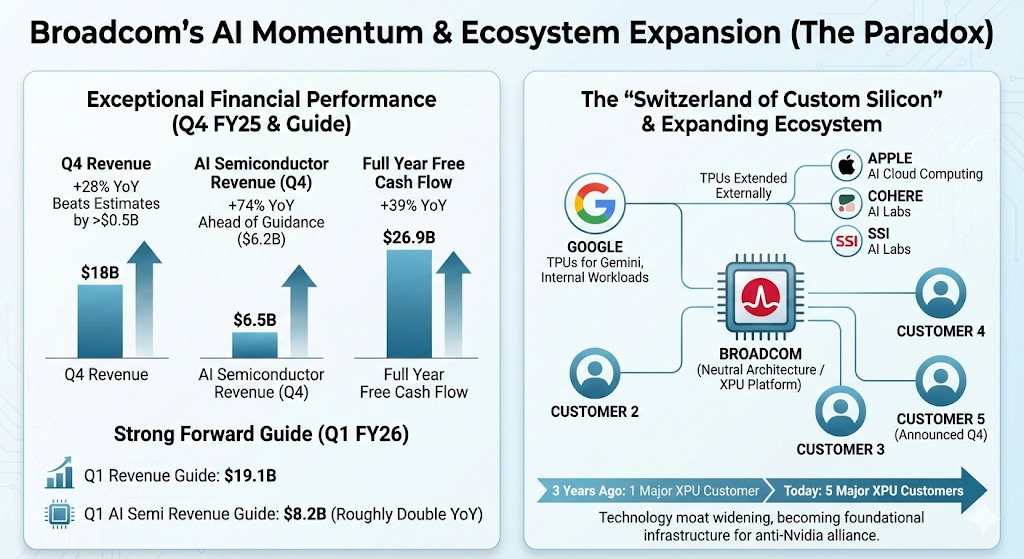

Fourth quarter revenue hit $18 billion, beating Wall Street estimates by more than half a billion dollars. AI semiconductor revenue reached $6.5 billion, comfortably ahead of management’s own $6.2 billion guidance and up 74% from the prior year. Free cash flow for the full fiscal year came in at $26.9 billion, up 39%. The forward guide was equally strong: Q1 revenue of $19.1 billion, with AI semiconductors expected to reach $8.2 billion — roughly double the year-ago quarter.

Here is how CEO Hock Tan described the AI momentum on the earnings call:

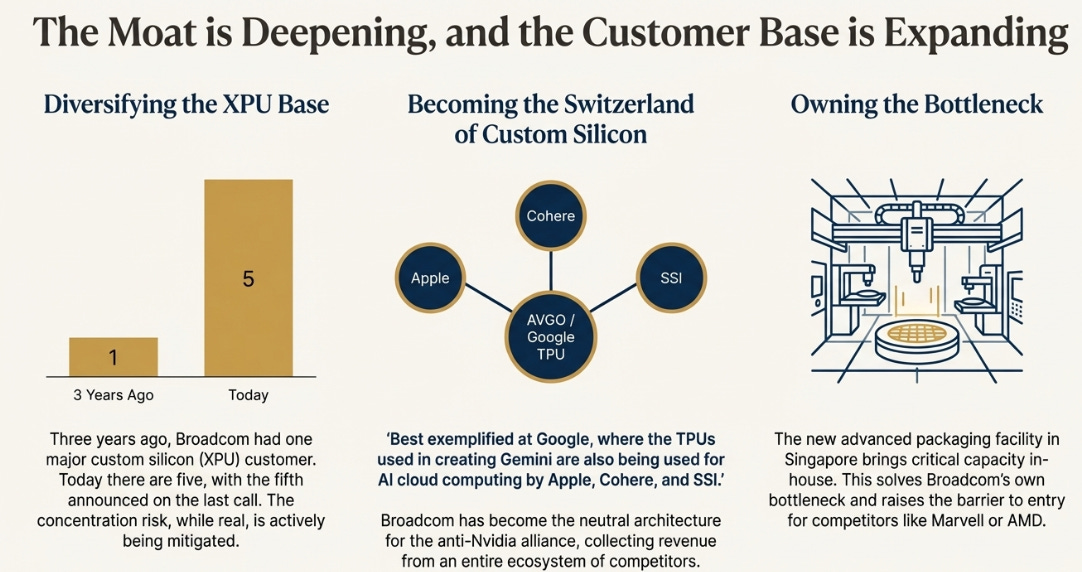

“Our customer accelerator business more than doubled year over year. As we see our customers increase adoption of XPUs, as we call those custom accelerators, in training their LLMs and monetizing their platforms through inferencing, APIs and applications. These XPUs, I may add, are not only being used to train and inference internal workloads by our customers. The same XPUs in some situations have been extended externally to other LLM players. Best exemplified at Google, where the TPUs used in creating Gemini are also being used for AI cloud computing by Apple, Cohere, and SSI.”

The implications of that paragraph deserve unpacking. Broadcom has quietly become the neutral architecture for the anti-Nvidia alliance. While Nvidia builds walled gardens with CUDA — proprietary software that locks customers into their ecosystem — Broadcom has positioned itself as the Switzerland of custom silicon: unthreatening to any individual hyperscaler’s ambitions, indispensable to their infrastructure, and embedded so deeply that switching costs compound with each generation.

Google’s TPUs, designed in partnership with Broadcom for over a decade, now power not just Google’s internal Gemini models but Apple’s AI infrastructure, Anthropic’s Claude, and a growing roster of frontier AI labs. The custom silicon that started as Google’s internal project has become shared infrastructure for an entire ecosystem of competitors. And Broadcom sits at the center of it, collecting revenue from all sides.

Three years ago, Broadcom had one major XPU customer. Today there are five, with the fifth announced on this very call. The technology moat isn’t narrowing. It’s becoming the foundation for everyone who wants an alternative to Nvidia’s dominance.

By any operational measure, this was a quarter that validates the bull thesis. And yet the stock dropped. Understanding why requires understanding the collision between two different economies operating in AI.

The Misunderstanding

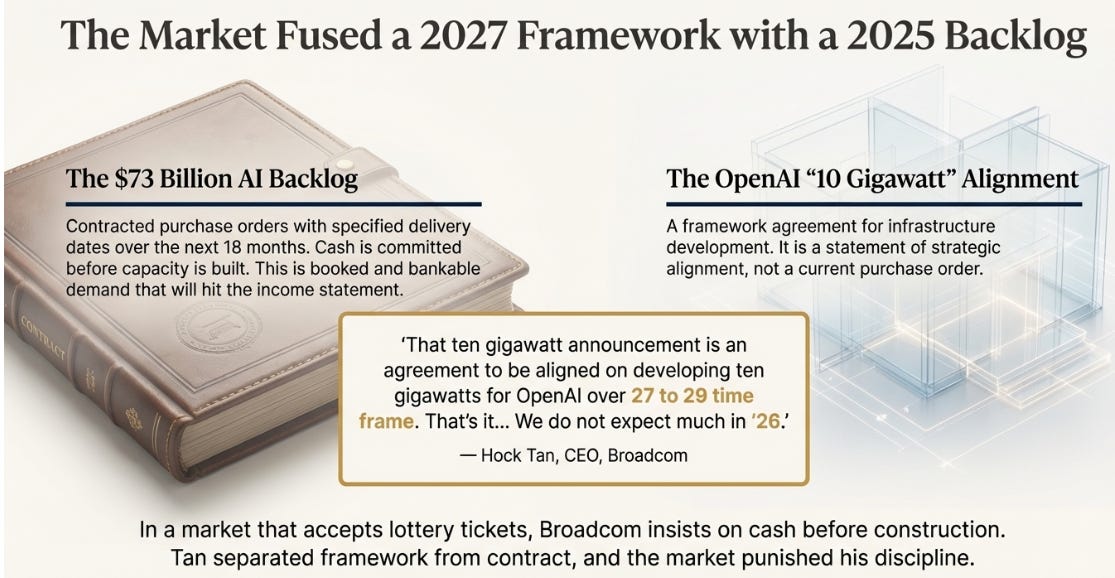

The sell-off traces back to OpenAI — or more precisely, to the gap between what investors had assumed and what Broadcom actually said.

Earlier this quarter, Broadcom announced a framework agreement with OpenAI around building “10 gigawatts” of AI infrastructure. The headlines were breathless. Broadcom wins OpenAI. Another hyperscaler locked in. The bull case accelerates into 2026.

On the earnings call, Tan separated reality from narrative with unusual precision:

“That ten gigawatt announcement is all about... I call it an agreement in alignment of where we’re headed... But what I was articulating earlier was the ten gigawatt announcement and that ten gigawatt announcement is an agreement to be aligned on developing ten gigawatts for OpenAI over 27 to 29 time frame. That’s it. That’s different from the XPU program we’re developing with them.”

And then, the line that moved the stock:

“We do not expect much in ‘26... it’s more like 27, 28, 29.”

The market had fused two distinct things into a single narrative. First: Broadcom’s $73 billion AI backlog, which represents contracted purchase orders with delivery dates over the next eighteen months. Second: the OpenAI “10 gigawatt” announcement, which generated headlines about Broadcom becoming OpenAI’s infrastructure partner.

Tan separated them explicitly. The backlog is contracted demand that will hit the income statement. The OpenAI framework is a statement of strategic alignment for 2027-2029 — real in its intent, but not a purchase order, not booked revenue, not a 2026 catalyst.

One is physics. The other is narrative. Tan told investors which was which, knowing it would hurt the stock.

This is where Broadcom diverges from nearly every other company in AI. The standard playbook is to maximize ambiguity. Announce the partnership. Let investors assume it means near-term revenue. Ride the stock appreciation. Clarify the details later, if ever.

Tan did the opposite. He drew the distinction on a public earnings call, in unambiguous language, separating framework from contract and 2027 from 2026. In a market where everyone else accepts lottery tickets, Broadcom insists on cash before construction.

The Anthropic Contrast

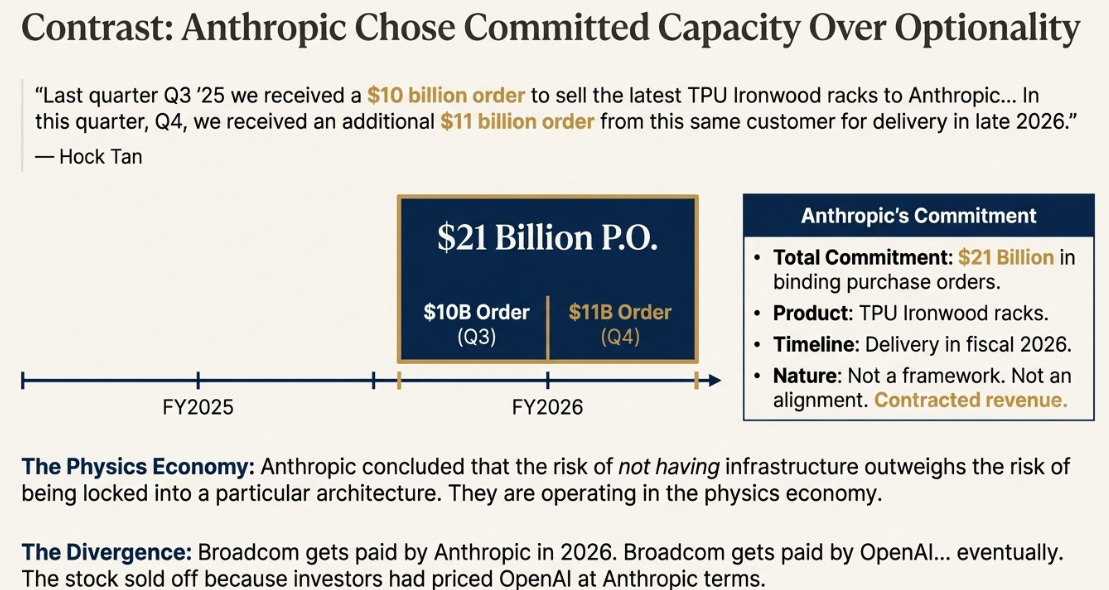

The contrast with Anthropic makes Broadcom’s discipline concrete.

Here is Tan describing the relationship with what he calls “customer number four”:

“Last quarter Q3 ‘25 we received a $10 billion order to sell the latest TPU Ironwood racks to Anthropic. And this was our fourth customer that we mentioned. And in this quarter, Q4, we received an additional $11 billion order from this same customer for delivery in late 2026.”

That’s $21 billion in binding purchase orders from a single customer, with specific delivery timelines in fiscal 2026. Not a framework. Not an agreement in alignment. Contracted revenue with delivery dates that Broadcom can plan capacity around.

The divergence between OpenAI and Anthropic reveals something important about the maturity curve of AI infrastructure. OpenAI, valued at $500 billion with seemingly unlimited access to narrative capital, can afford to keep options open. They can sign framework agreements, preserve flexibility, and wait to see how the competitive landscape evolves before committing billions to specific hardware architectures. The luxury of optionality comes from the luxury of valuation.

Anthropic made a different calculation. They looked at the AI infrastructure landscape and decided that committed capacity beats optionality. They signed binding contracts. They locked in delivery dates. They will take physical possession of TPU Ironwood racks in 2026 while OpenAI is still finalizing frameworks for 2027-2029.

There’s a lesson here about what it means to operate in the physics economy. When you’re building real infrastructure, shipping real products, and can’t afford to wait for vaporware to materialize, you lock in proven capacity at the cost of flexibility. Anthropic concluded that the risk of not having infrastructure outweighs the risk of being locked into a particular architecture.

Broadcom gets paid by Anthropic in 2026. Broadcom gets paid by OpenAI... eventually. If frameworks convert to contracts. If the 10 gigawatts get built. If the custom silicon program advances from “very advanced stage” to actual purchase orders.

The stock sold off because investors had priced OpenAI at Anthropic terms. Tan told them the difference.

The Real Story: Becoming the Infrastructure Architect

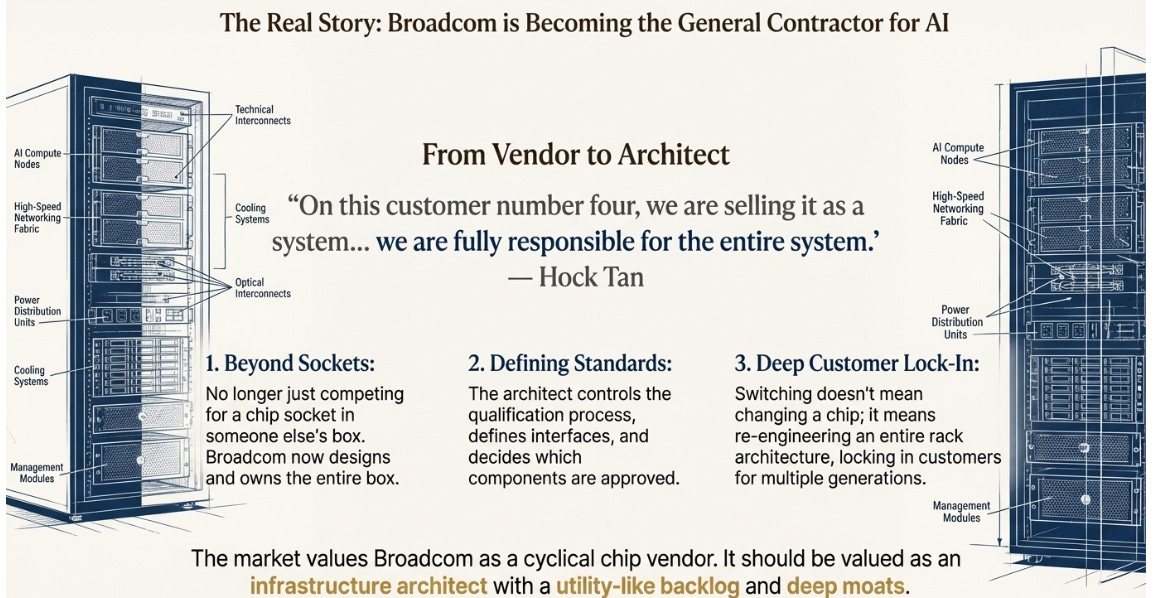

The OpenAI timing is a legitimate recalibration. But it’s not the most important thing that happened on this earnings call. The most important thing is what Broadcom is becoming.

Listen to how Tan describes the Anthropic relationship:

“On this customer number four, we are selling it as a system with our key components in it. It’s a system sale... we are fully responsible for the entire system.”

And on what that means for the financial profile:

“We’ll be passing through more components that are not ours... gross margins will go down, operating margin dollars will go up.”

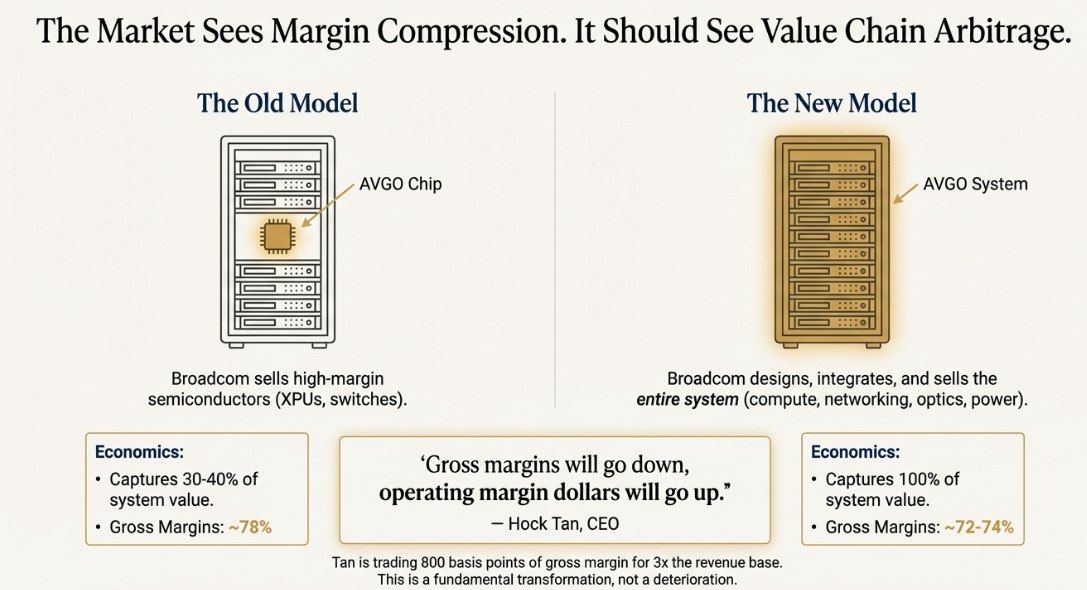

This is a fundamental transformation of Broadcom’s business model, and the market is completely missing it.

The old model worked like this: Broadcom designed and sold semiconductors — custom AI accelerators, networking switches, optical components — to server manufacturers or directly to hyperscalers, who integrated them into systems. Broadcom captured component value at very high gross margins (77-78%), but only on a portion of total system cost. The rest of the value — memory, power delivery, mechanical integration, everything else in the rack — went to other vendors.

The new model works differently. Broadcom designs, integrates, and takes full responsibility for complete AI racks. Compute, networking, optics, power delivery — the entire system. They pass through third-party components they don’t manufacture themselves, which pushes gross margins down. But they capture 100% of the system value instead of 30-40%, which means absolute profit dollars multiply even as percentages decline.

Tan is trading 800 basis points of gross margin for 3x the revenue base. That’s not margin compression. That’s value chain arbitrage.

The strategic implications matter more than the financial ones. When you’re responsible for the entire system, you’re no longer a vendor competing for sockets. You’re an architect defining standards. You control the qualification process. You decide which components are approved and which aren’t. You design the interfaces between subsystems. The hyperscaler becomes locked into your architecture for multiple generations because switching doesn’t mean just changing a chip — it means re-engineering the entire rack.

The market sees gross margin declining from 78% toward 72-74% and interprets it as deterioration. What they should see is Broadcom transforming from a semiconductor component company into the general contractor for AI infrastructure — from selling chips into someone else’s box to designing and taking responsibility for the entire box.

This is the transformation that justifies a different multiple. A chip vendor trades at semiconductor multiples, subject to cycles and commoditization risk and customer concentration concerns. An infrastructure architect with multi-generational lock-in and $73 billion in contracted backlog trades at utility multiples. The market hasn’t made that repricing yet.

The new advanced packaging facility in Singapore reinforces this strategic position. Broadcom is bringing significant packaging capacity in-house, which doesn’t just solve their own bottleneck — it raises the barrier to entry for every competitor trying to challenge them in custom AI silicon. If you’re Marvell or AMD trying to compete, you now need to solve both chip design and advanced packaging at Broadcom’s scale. The number of companies that can do that is very small and getting smaller.

The risk is real and worth stating plainly: Google concentration. Google likely represents 40-50% of Broadcom’s AI semiconductor revenue, directly or through downstream customers like Anthropic running on TPU infrastructure. If Google decided to in-source TPU design, Broadcom would have a serious problem.

But in-sourcing would take 5+ years and require building a world-class semiconductor design organization from scratch. Google once tried to design their own networking chips. They failed and came back to Broadcom. Meanwhile, the customer base is diversifying — five XPU customers now, up from one three years ago, with the OpenAI program progressing regardless of near-term timing. The concentration is real but the trajectory favors Broadcom.

The Cash Engine

One more piece makes the entire model work: VMware.

The infrastructure software business that Broadcom acquired for $69 billion — and that many analysts worried was a melting ice cube being harvested for cash — just reported Q4 revenue of $6.9 billion at 78% operating margin. Software backlog stands at $73 billion, up from $49 billion a year ago. This is not a declining asset. This is a quasi-utility annuity generating billions in free cash flow every quarter.

That cash flow is what allows Broadcom to play the long game on AI. It funds 2nm and 3nm chip designs without diluting shareholders. It funds the Singapore packaging facility without excessive leverage. It provides a floor if AI capital expenditure pauses for digestion. The combination of growing AI franchise plus durable software cash engine is rarer than the market appreciates. It’s what allows Tan to tell investors the truth about OpenAI timelines rather than spinning narratives to prop up the stock price.

When your cash engine is solid, you can afford to be honest. That’s a luxury most AI companies don’t have.

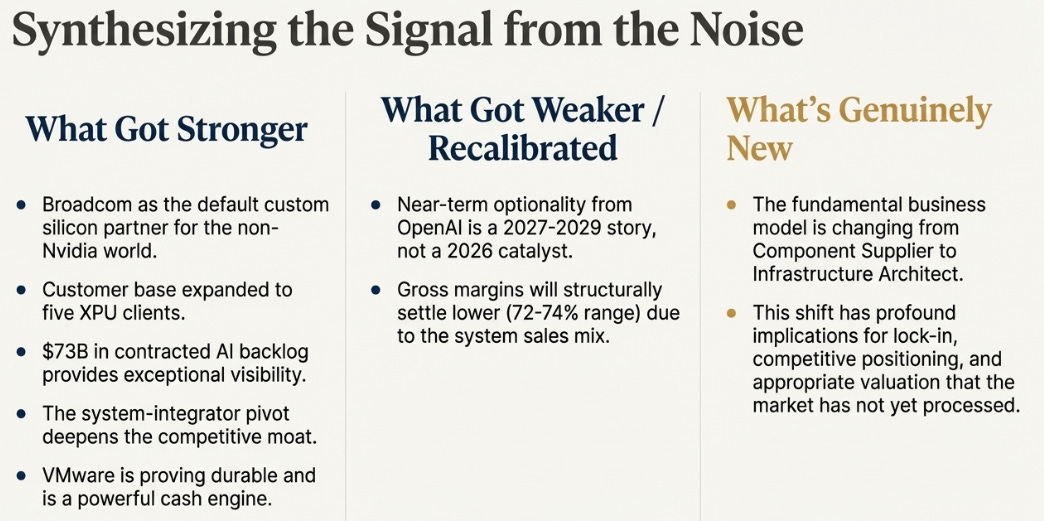

What Changed

What got stronger: The evidence that Broadcom is the default custom silicon and networking partner for serious AI infrastructure outside Nvidia. Five XPU customers, up from one. $73 billion in AI backlog with delivery visibility. Anthropic doubling down with $21 billion committed. The system-integrator pivot deepening the moat with every rack shipped. VMware proving durable rather than depleting.

What got weaker: Near-term OpenAI optionality. The framework agreement is real strategic alignment, but it’s a 2027-2029 story, not a 2026 EPS catalyst. Some of the bull case moves out by 12-24 months. Gross margins will structurally settle lower as system sales become a larger portion of the mix.

What’s genuinely new: Broadcom is changing what kind of company it is. The shift from component supplier to infrastructure architect has implications for competitive positioning, customer lock-in, and appropriate valuation that the market hasn’t fully processed.

Scenarios

Bull (30% probability): OpenAI converts the framework agreement to binding purchase orders by mid-2026. A sixth or seventh XPU customer emerges from the remaining hyperscalers. Gross margins stabilize above 74% as system sales mix normalizes. The market rerates Broadcom as an infrastructure utility rather than a cyclical semiconductor company. Stock to $500+.

Base (50% probability): AI revenue doubles in fiscal 2026 as guided, driven by existing customer ramps. OpenAI contributes meaningful revenue starting in fiscal 2027-28. VMware continues compounding at low double-digits. Gross margins settle in the 74-75% range as the system business scales. Stock grinds higher to $450-480 over the next 12-18 months on earnings growth.

Bear (20% probability): OpenAI delays significantly or diversifies across multiple silicon suppliers. AI revenue growth decelerates below 40% without clear explanation. Gross margins compress below 72%, suggesting the system pivot economics don’t work as modeled. Stock revisits $320-350.

Checkpoints

Q1 AI Revenue (February): Does AI semiconductor revenue hit the $8.2 billion guide? This is the most immediate test of execution and validates the doubling trajectory.

Gross Margin Trough (Q2): Does consolidated gross margin stabilize above 72%? This tests whether the system pivot math actually works or whether Broadcom is giving away economics for revenue.

OpenAI Conversion (by Q3 FY26): Any binding purchase order emerging from the framework agreement? This tests whether the 10GW announcement represented genuine intent or negotiating leverage.

Customer Six (by mid-CY26): Another major XPU customer win announced? This tests the diversification thesis and begins to address Google concentration concerns.

VMware Volume (Q2): Is software revenue growing on volume, not just price increases? This tests whether the cash engine is sustainable or being harvested.

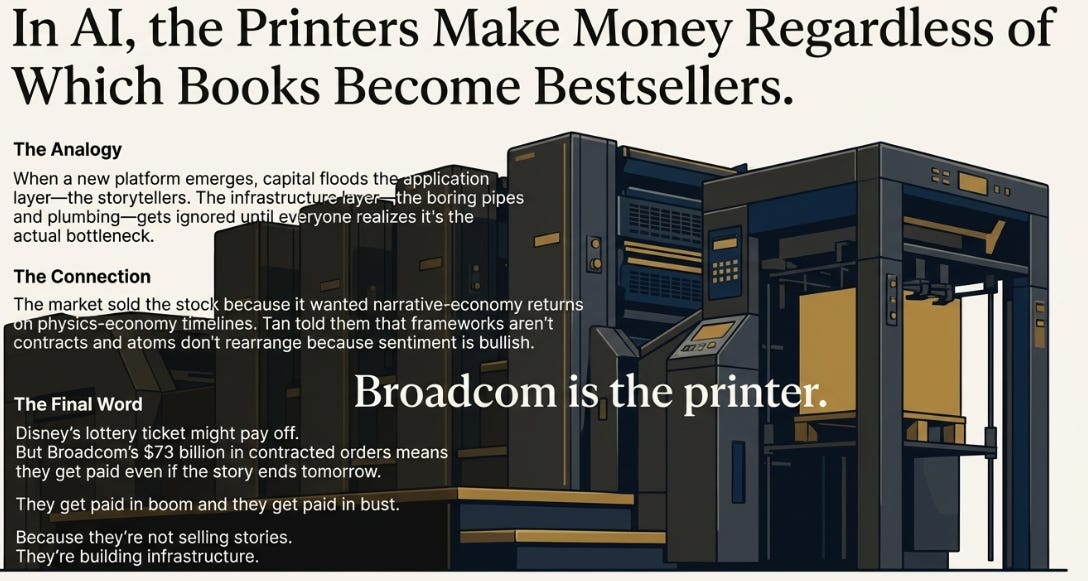

The Printers

There is a pattern that repeats in technology transitions. When a new platform emerges, capital floods toward the application layer — the storytellers, the dream merchants, the companies selling picks to prospectors. The infrastructure layer, the boring pipes and plumbing underneath, gets ignored until everyone realizes it’s the actual bottleneck. Then the repricing happens, but by then the infrastructure companies have already built their moats.

AI is following the script with remarkable fidelity. Billions flow to foundation model companies trading at narrative valuations — $500 billion for OpenAI, with compensation structures built on warrants and future fundraising rounds. Meanwhile, the companies building actual infrastructure — the custom silicon, the networking fabric, the racks, the data centers — operate on physics-economy rules. Contracted orders before capacity builds. Cash before construction. Eighteen-month lead times that don’t compress because sentiment is bullish.

Broadcom just reported a quarter demonstrating that the physics economy works. More customers than ever. More backlog than ever. Deeper integration than ever. A business model evolving from chip vendor to infrastructure architect. And a CEO disciplined enough to tell investors the truth about what’s contracted versus what’s aspirational, even when the truth costs him 5% in after-hours trading.

The market sold the stock because it wanted narrative-economy returns on physics-economy timelines. Investors expected the OpenAI framework to convert instantly into 2026 EPS. Tan told them that frameworks aren’t contracts, that 2027 isn’t 2026, and that atoms don’t rearrange themselves because sentiment is bullish.

Disney’s lottery ticket might be worth billions if OpenAI hits a $750 billion valuation in its next funding round. The warrants will appreciate. The press releases will celebrate the vision.

But Broadcom’s $73 billion in contracted orders means they get paid even if the story ends tomorrow. They get paid if OpenAI succeeds and they get paid if OpenAI stumbles. They get paid in boom and they get paid in bust. Because they’re not selling stories. They’re building infrastructure.

In AI, as in publishing, the printers make money regardless of which books become bestsellers.

Broadcom is the printer.

Disclaimer:

The content does not constitute any kind of investment or financial advice. Kindly reach out to your advisor for any investment-related advice. Please refer to the tab “Legal | Disclaimer” to read the complete disclaimer.