DoorDash: The Ice King and the Last Mile

Why controlling reliability—not selling food—built a $70B logistics empire, and why the market may be pricing permanence that history rarely grants.

TL;DR

DoorDash’s real innovation wasn’t food delivery, it was integrating logistics so reliability became the product, just as Frederic Tudor did with ice.

New verticals and advertising monetization face structural ceilings the market underestimates, especially in grocery and international markets.

At today’s valuation, investors are paying for infrastructure that may compound, or be quietly obsoleted by the next “refrigeration moment.”

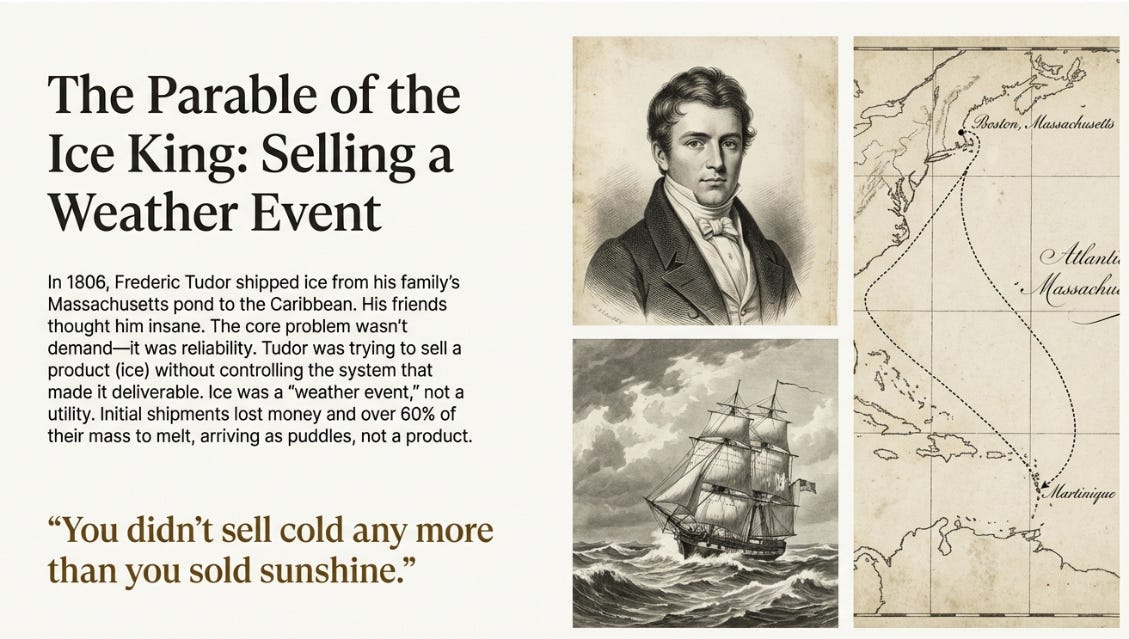

In 1806, a twenty-three-year-old Bostonian named Frederic Tudor loaded a brig with ice cut from his family’s pond and sailed for the Caribbean. His friends thought him insane. Ice was not a product—it was a weather event. You didn’t sell cold any more than you sold sunshine. The ice would melt. The voyage would fail. Tudor would be ruined.

He was nearly ruined. That first shipment to Martinique lost money. So did the next several. The problem wasn’t demand—colonists in the tropics were desperate for cold drinks and fresh food preservation. The problem was that Tudor was trying to sell a product without controlling the system that made it deliverable. Ice harvested in Massachusetts and loaded onto a ship would lose 60% of its mass to melt before reaching Havana. What arrived was a puddle, not a product.

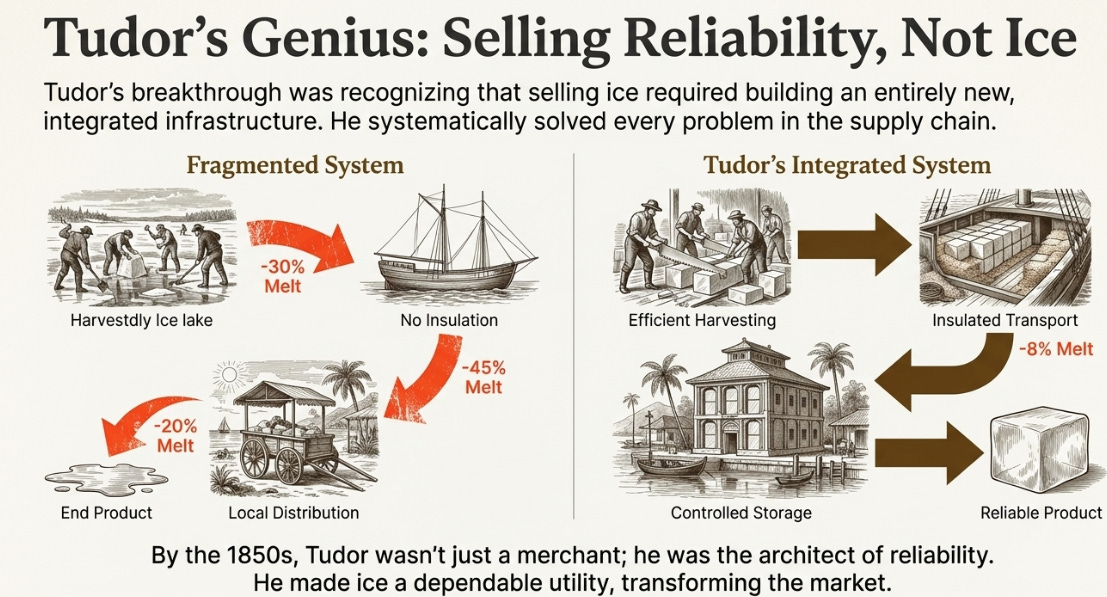

Tudor’s genius wasn’t recognizing that people wanted ice. It was recognizing that selling ice required building an entirely new infrastructure. He couldn’t just be a merchant; he had to become an architect of reliability.

Over the next three decades, Tudor systematically solved every problem in the ice supply chain. He invented better harvesting tools that cut uniform blocks. He designed insulated ships with sawdust-packed holds that reduced melt rates dramatically. Most importantly, he built ice houses—heavily insulated storage facilities in tropical ports that could keep ice frozen for months. He constructed these ice houses in Havana, New Orleans, Charleston, and eventually Calcutta, often at his own expense, before local demand existed to justify them.

By the 1850s, Tudor had transformed ice from a curiosity into a utility. Boston alone was shipping 150,000 tons annually to destinations across the globe. Tudor died one of the wealthiest men in America, not because he sold ice, but because he built the integrated system that made ice reliable enough to become a daily expectation.

The lesson was not about ice. It was about what happens when someone takes a fragmented, unreliable experience and engineers it into something people can depend on without thinking. That transformation—from weather event to utility—requires integration. You cannot make a promise about the end product if you don’t control the system that delivers it.

This same transformation is now playing out in local commerce. And the company attempting it most ambitiously is DoorDash.

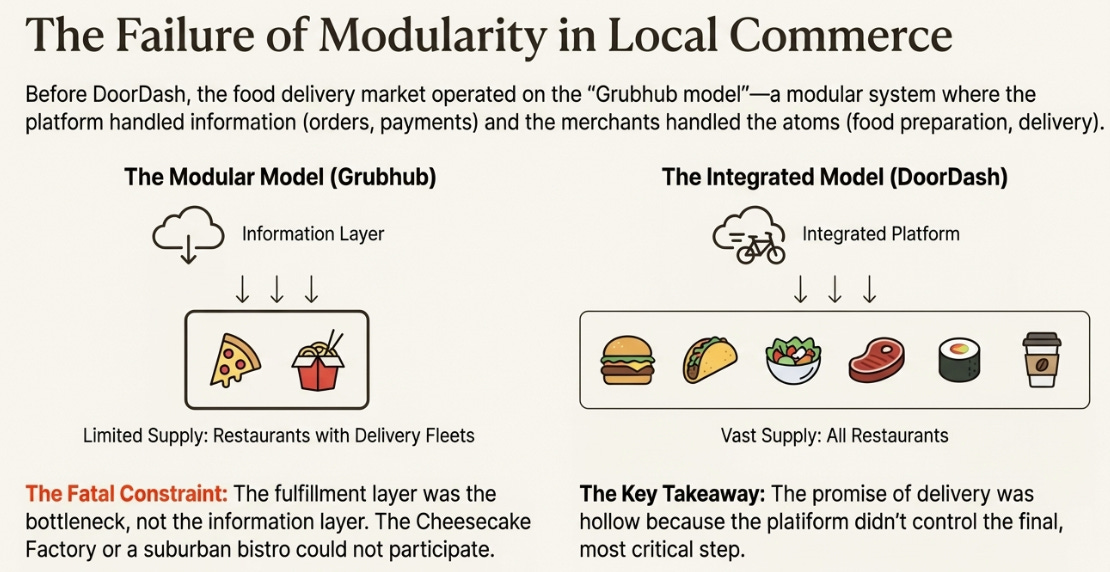

The Failure of Modularity

Before DoorDash’s rise, food delivery operated on what might be called the “Grubhub model”—a modular system where the platform handled information (menus, orders, payments) while merchants handled atoms (preparation, delivery). This seemed elegant. The platform could scale infinitely by adding restaurants to its directory. Restaurants could access digital demand without building technology. Everyone stayed in their lane.

The model had a fatal constraint: it limited supply to restaurants that already possessed delivery infrastructure. In practice, this meant pizza chains and Chinese takeout in urban centers. The Cheesecake Factory couldn’t participate because it had no delivery fleet. Neither could the suburban bistro or the lunch spot in a strip mall. The information layer was scalable, but the fulfillment layer wasn’t—and fulfillment was the bottleneck.

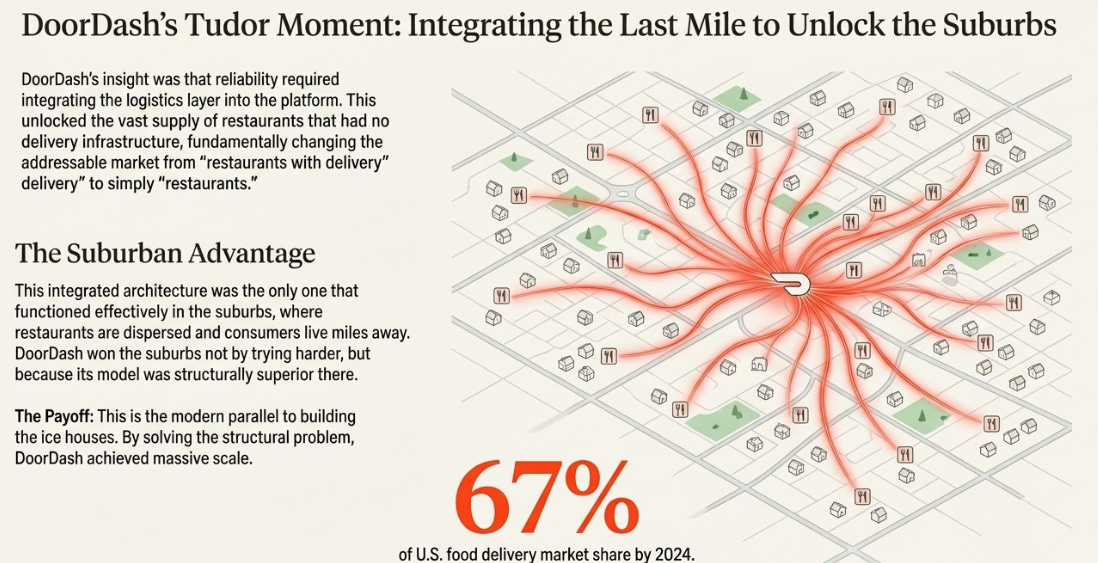

DoorDash’s insight was that you couldn’t build a reliable system on top of unreliable components. If the platform promised delivery but the merchant controlled whether delivery actually happened, the promise was hollow. The only way to make local commerce feel like a utility was to integrate the logistics layer into the platform itself.

This integration unlocked supply that couldn’t exist under the modular model. Suddenly any restaurant could offer delivery, regardless of whether they’d ever considered it. The addressable market expanded from “restaurants with delivery fleets” to “restaurants.” That’s a categorical difference.

The integration worked best in suburbs—precisely the markets where Grubhub was weakest. Suburban restaurants had no delivery infrastructure. Suburban consumers lived miles from their preferred dining options. The modular model couldn’t serve these markets profitably; the integrated model could. DoorDash didn’t win suburbs because it tried harder. It won because its architecture was the only one that functioned there.

This is the Tudor pattern: build the ice houses before demand exists, integrate the supply chain others left fragmented, and make reliability the product. By 2024, DoorDash had captured 67% of U.S. food delivery—a dominance built not on subsidies or marketing, but on solving the structural problem competitors hadn’t recognized as structural.

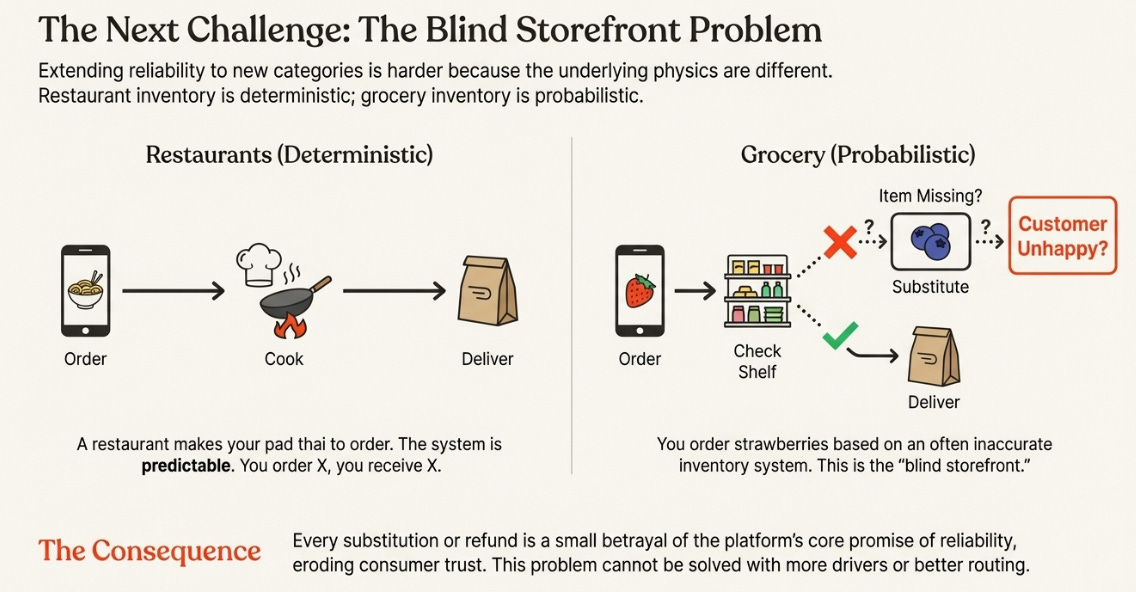

The Blind Storefront

If the first phase of DoorDash’s evolution was integrating restaurant logistics, the second phase is far more difficult: extending that reliability to categories where the underlying physics are fundamentally different.

When you order pad thai, the restaurant makes it fresh. The inventory question is trivial—restaurants stock ingredients, not finished meals. The system is deterministic: you order X, you receive X.

Grocery is probabilistic. When you order strawberries, you’re betting they’re actually on the shelf. The app thinks they’re there. The store’s inventory system thinks they’re there. But inventory systems are notoriously inaccurate—items get misplaced, spoil, or sell out between the last system update and your order. The result is substitutions, refunds, and eroded trust. Every “we replaced your strawberries with blueberries” message is a small betrayal of the reliability promise.

This is the “blind storefront” problem. DoorDash can see menus perfectly because restaurants publish them. It cannot see grocery inventory accurately because retailers don’t have that data themselves in real-time. The information layer is lying to the fulfillment layer, and the consumer experiences the lie as poor service.

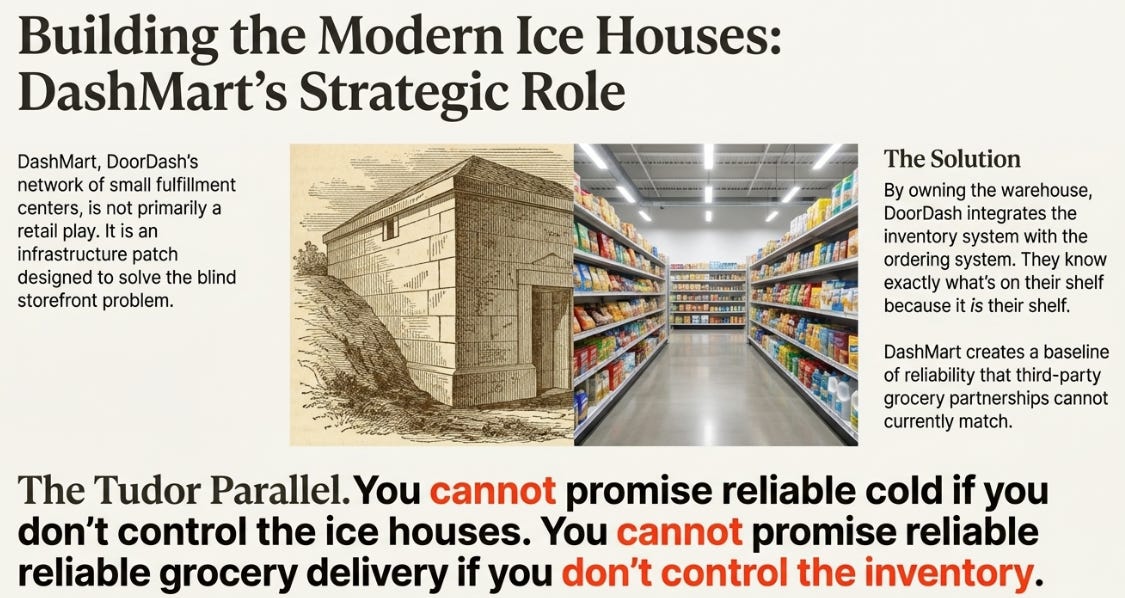

The strategic implications are significant. DoorDash’s grocery ambitions: which have driven 80%+ growth in new verticals, face a constraint that more drivers and better routing cannot solve. The problem is upstream, in the inventory systems DoorDash doesn’t control.

This explains DashMart. The company’s network of small fulfillment centers isn’t primarily a retail play—it’s an infrastructure patch. By owning the warehouse, DoorDash integrates the inventory system with the ordering system. They know exactly what’s on the shelf because it’s their shelf. DashMart sets a reliability baseline that third-party grocery partnerships cannot currently match.

Whether DoorDash can pressure traditional retailers to fix their inventory data, or must build more owned fulfillment to achieve grocery reliability, remains the central operational question of the next three years. The Tudor parallel holds: you cannot promise reliable cold if you don’t control the ice houses.

When Reliability Becomes Monetizable

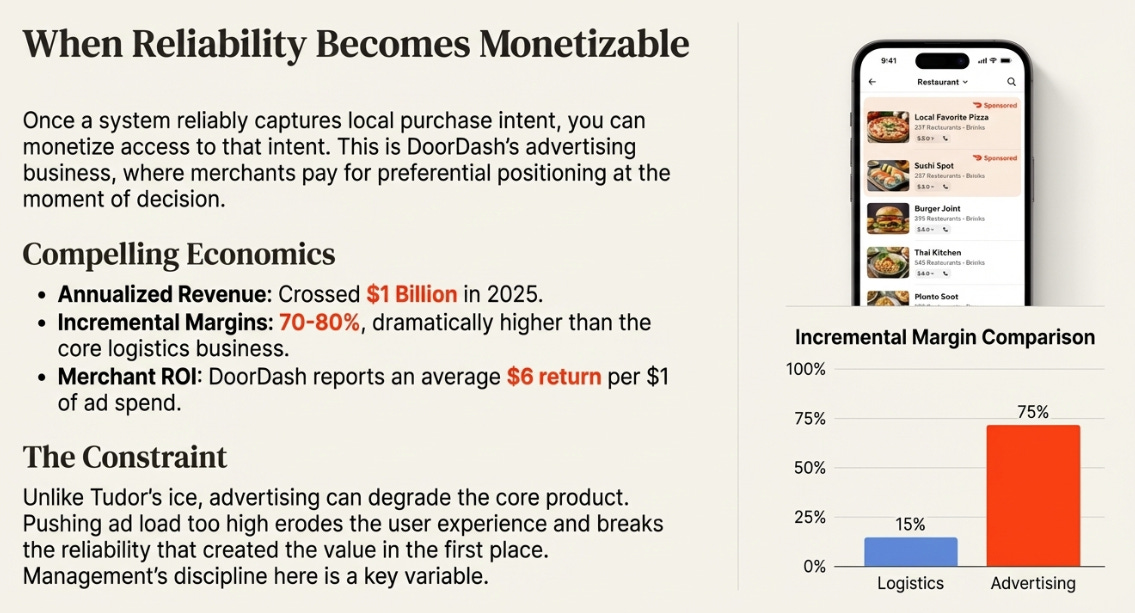

Tudor’s ice business had a simple revenue model: sell ice by the pound. Once he’d built the infrastructure that made ice reliable in the tropics, he could charge what the market would bear.

DoorDash’s monetization is more layered, but the underlying logic is identical. Once you’ve built a system that reliably captures local purchase intent: once consumers open your app by default when they want something nearby, you can monetize access to that intent without raising consumer prices.

This is the advertising business. DoorDash’s sponsored listings and promoted placements crossed $1 billion in annualized revenue in 2025. Merchants pay to be visible at the moment a consumer is deciding what to order. The consumer pays the same delivery fee regardless; the merchant pays for preferential positioning.

The economics are compelling. Advertising revenue carries 70-80% incremental margins, dramatically higher than the logistics business. And unlike raising delivery fees (which consumers resist) or raising commission rates (which merchants resist), advertising is a voluntary expenditure by merchants who believe the return justifies the cost. DoorDash reports average return on ad spend of roughly $6 per $1 invested.

But there’s a constraint Tudor didn’t face. His ice houses couldn’t degrade the ice. DoorDash’s advertising can degrade the user experience. Every promoted listing that displaces a better organic result erodes the reliability that made the platform valuable in the first place. Push ad load too high, and you break the system you’re monetizing.

DoorDash management emphasizes this constraint constantly, perhaps too constantly, in a way that suggests they’re building a pre-commitment device against future temptation. They frame advertising success in terms of merchant ROI and consumer conversion, not revenue growth. The message: we will not sacrifice the system to monetize it faster.

Whether that discipline holds when growth slows, when the pressure to demonstrate margin expansion intensifies, is a question only time will answer. For now, advertising represents the highest-margin component of DoorDash’s business and the clearest evidence that reliability can compound into durable monetization power.

The Competition That Shapes Strategy

Tudor operated in an era without meaningful competition. He’d built infrastructure no one else possessed; by the time rivals recognized the opportunity, his ice houses dotted ports across the globe.

DoorDash faces a more complex competitive landscape: one that shapes its strategic choices in ways the Tudor analogy alone cannot capture.

Meituan in China represents the fullest expression of where local commerce platforms can go. With 150 million daily orders and complete integration across food, grocery, hotels, travel, and local services, Meituan has become the default interface for urban Chinese consumers seeking anything nearby. They’ve proven that high-frequency food delivery can be the hook that sells high-margin adjacent services.

Uber represents the horizontal integration model. By combining mobility (rides) and delivery (Eats), Uber achieves utilization advantages: drivers can switch between passengers and packages based on demand, reducing idle time. The same consumer can book a ride and order dinner from a single app with a single payment method. Uber’s strategic DNA is transportation efficiency, not local commerce depth.

DoorDash has neither Meituan’s super-app breadth nor Uber’s rides business. This constraint is clarifying. Without a profitable adjacent business to subsidize delivery, DoorDash must make delivery itself economically sustainable, and find margin in layers Uber doesn’t prioritize.

This explains DoorDash’s push into merchant services. The SevenRooms acquisition (restaurant CRM and reservations), the expansion of DoorDash Drive (white-label delivery for merchants’ own channels), the integration with point-of-sale systems—all represent a strategic bet that depth with merchants compensates for lack of breadth with consumers.

The implicit wager: in Western markets, merchants like Starbucks, Sephora, and Kroger are too powerful to fully disintermediate. They won’t cede their customer relationships to a platform the way smaller restaurants have. So DoorDash positions itself as infrastructure: the logistics and technology layer that powers merchants’ own commerce, rather than only as a marketplace that intermediates between merchants and consumers.

Whether this B2B positioning can generate sufficient margin to justify DoorDash’s valuation, when the B2C marketplace remains the vast majority of revenue, is among the most important uncertainties facing investors.

The Cost of Empire

By 2025, DoorDash had assembled a global footprint through acquisition: the original U.S. business, Wolt across Europe and Asia, and Deliveroo in the UK and additional European markets. Combined, the company operates in 45 countries with over 50 million monthly active users.

The problem: three companies means three technology stacks. Features built for DoorDash U.S. must be rebuilt for Wolt, then rebuilt again for Deliveroo. The advertising platform that works in San Francisco doesn’t automatically function in Berlin. The merchant tools refined in Chicago must be re-engineered for London.

This is more than inefficiency. It’s a velocity constraint. In a business where competitive advantage accrues to whoever ships improvements fastest, running three parallel development efforts is a structural handicap.

DoorDash’s 2026 investment plan, disclosed as “several hundred million dollars more” than 2025, directly addresses this problem. The company is building a unified global technology platform, consolidating the separate stacks into a single architecture that can deploy features simultaneously across all markets.

Management frames this as building an “AI-native” platform, though the more prosaic description is probably more accurate: they’re paying down technical debt accumulated through rapid acquisition, while modernizing the foundation for future development speed.

The market’s initial reaction was negative. The stock fell 15-20% after the Q3 2025 earnings call, as investors processed that margin expansion would be delayed by investment. Analyst price targets dropped 10-20%.

But the strategic logic is sound. A holding company that owns three separate delivery businesses is less valuable than an integrated operating system that happens to serve 45 countries. The former is a collection of assets; the latter is a platform with compounding advantages in development speed, operational efficiency, and global consistency.

The risk is execution. Large platform rewrites are where good companies lose momentum. They take longer than planned, cost more than budgeted, and often fail to deliver promised benefits. DoorDash is attempting this rewrite while simultaneously integrating acquisitions, expanding into new categories, and competing with well-funded rivals.

Management’s stated timeline, full benefits arriving in “2029 and 2030” is extraordinarily long for a technology investment. Four to five years is enough time for the competitive landscape to shift dramatically. The platform being built may arrive into a world that’s moved on.

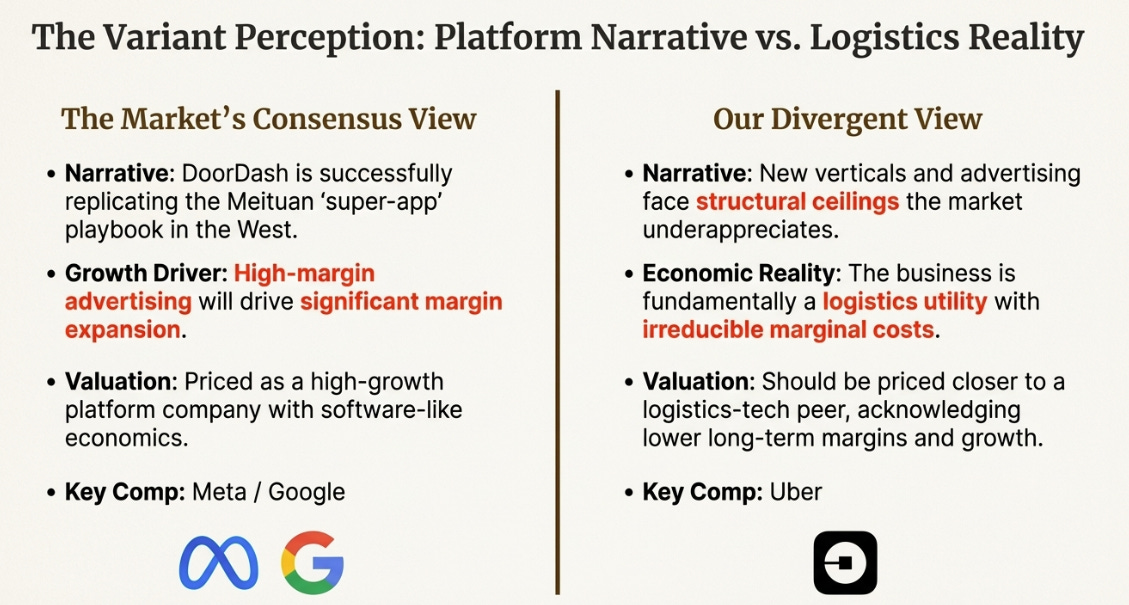

The Variant Perception

The market’s consensus view on DoorDash can be summarized simply: this is a growth company transitioning to profitability, successfully replicating the Meituan playbook in Western markets, with high-margin advertising providing the margin expansion that delivery logistics alone cannot generate.

At $220 per share and roughly 7x forward revenue, the stock prices in continued 20%+ growth, EBITDA margins expanding toward 20%, and successful execution on international integration, new verticals, and advertising growth.

I believe the consensus is partially wrong.

Where I agree: DoorDash is a dominant business with genuine competitive advantages. The 67% U.S. market share reflects real network effects. The advertising business is high-margin and growing. Management has demonstrated operational excellence in achieving GAAP profitability while sustaining strong growth.

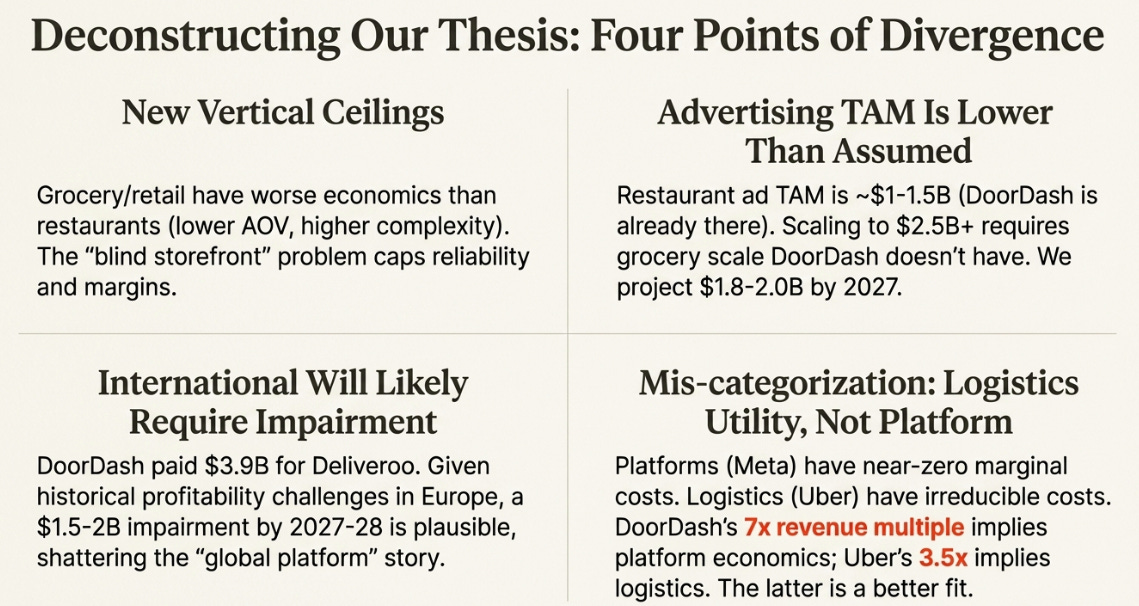

Where I diverge:

First, new verticals face structural margin challenges the market underappreciates. Grocery and retail have fundamentally different economics than restaurant delivery: lower average order values, higher pick complexity, and intense competition from Instacart, Amazon, and Walmart. The “blind storefront” inventory problem adds a reliability constraint that doesn’t exist in restaurants. These categories can grow large without ever achieving restaurant-level contribution margins.

Second, advertising growth is approaching a ceiling lower than consensus models assume. Restaurant marketing budgets are structurally small: a $1 million restaurant might have $30-50K for all marketing annually. At 590,000 merchants, the restaurant advertising TAM may be roughly $1-1.5 billion. DoorDash is already there. Scaling to the $2.5-3 billion figures embedded in some models requires capturing CPG advertising through grocery—which requires grocery scale DoorDash doesn’t yet have. I expect advertising reaches $1.8-2.0 billion by 2027, not $2.5 billion+.

Third, international will likely require an impairment. European food delivery has collectively destroyed over $20 billion in shareholder value. No company has achieved sustained profitability at scale. DoorDash paid $3.9 billion for Deliveroo: roughly 19x the $200 million EBITDA management guides for 2026. If Deliveroo delivers $120-150 million instead, and the market applies a 15x multiple to a slow-growth, marginally profitable business, the implied value is $1.8-2.2 billion. A $1.5-2 billion impairment by 2027-2028 would not destroy DoorDash, but would shatter the “global platform” narrative.

Fourth, the market is pricing DoorDash as a platform when the economics are closer to a logistics utility. Platforms like Google and Meta trade at high multiples because they have near-zero marginal costs and winner-take-all dynamics. Logistics businesses have irreducible marginal costs—you always need someone or something to move the atoms—and tend toward duopolies rather than monopolies. DoorDash’s 7x revenue multiple implies platform economics; Uber’s 3.5x multiple implies logistics economics. I believe DoorDash is closer to Uber than to Meta.

Why is the market mispricing this?

Narrative seduction. The “operating system for cities” story is intellectually compelling and invokes the most successful platform companies as comparisons. This framing causes analysts to extend growth rates further than fundamentals support and apply multiples appropriate for software to what remains primarily a logistics coordination business.

Coverage bias reinforces this.

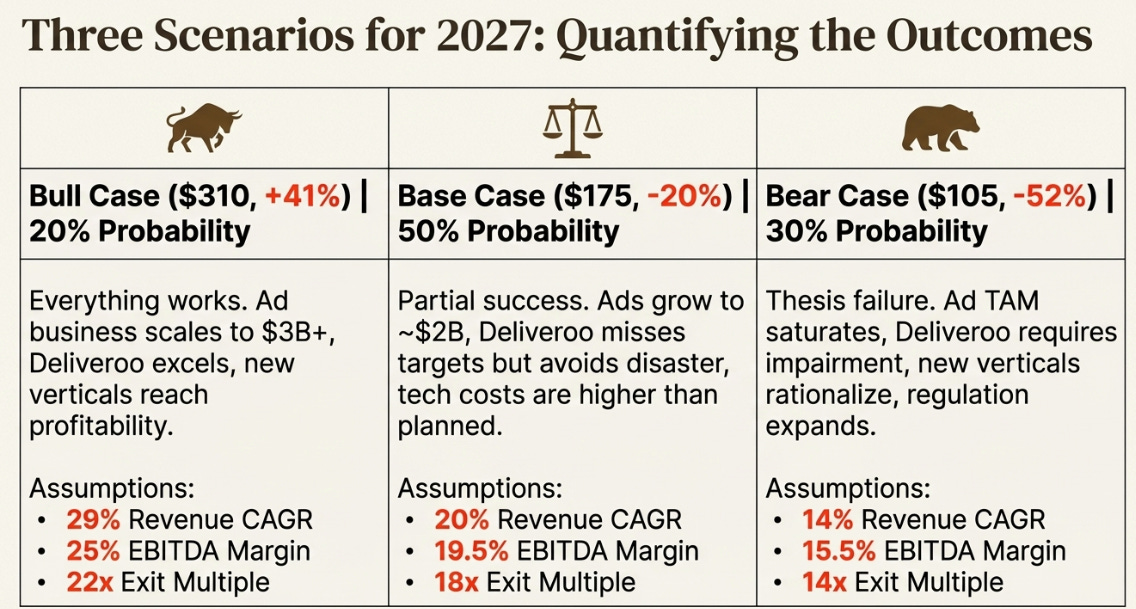

Three Scenarios for 2027

What will DoorDash be worth in three years? The answer depends on which version of the company materializes.

Bull Case: $310 (+41%) Probability: 20%

In this scenario, everything works. Advertising scales to $3 billion+ as grocery reaches sufficient scale to capture CPG budgets. Deliveroo achieves $250 million+ EBITDA, validating that operational discipline can overcome European delivery’s structural challenges. New verticals reach contribution profit by 2026. The technology platform investment delivers visible efficiency gains, and the unified stack accelerates feature deployment globally. Regulatory risk remains contained.

Assumptions:

Revenue CAGR 2024-2027: 29%

2027 Revenue: $23 billion

2027 EBITDA margin: 25%

2027 EBITDA: $5.75 billion

Exit multiple: 22x EBITDA

The math: $5.75B × 22 = $126.5B EV + ~$14B cumulative net cash = ~$140B market cap. At ~430M shares = ~$325, rounded to $310.

Base Case: $175 (-20%) Probability: 50%

The most likely outcome: partial success. Advertising grows 20-25% annually (not 35%), reaching roughly $2 billion by 2027. Deliveroo delivers $120-150 million EBITDA, missing the $200 million target but avoiding disaster. New verticals remain marginally unprofitable through 2027 but show improving trajectory. The technology platform costs exceed initial guidance, with benefits delayed to 2028+. International reaches contribution breakeven but isn’t a meaningful profit driver. Regulatory environment sees some expansion but remains manageable.

Assumptions:

Revenue CAGR 2024-2027: 20%

2027 Revenue: $18.5 billion

2027 EBITDA margin: 19.5%

2027 EBITDA: $3.6 billion

Exit multiple: 18x EBITDA (compression from current levels)

The math: $3.6B × 18 = $64.8B EV + ~$10B net cash = ~$75B market cap. At 430M shares = ~$175.

Bear Case: $105 (-52%) Probability: 30%

Multiple thesis elements fail. Advertising growth decelerates to 15% as restaurant TAM saturates and grocery doesn’t scale. Deliveroo requires a $1.5 billion+ impairment as European profitability proves elusive. New verticals never reach contribution profit; management eventually rationalizes the portfolio. The technology platform runs significantly over budget and behind schedule. Regulatory expansion to 100+ jurisdictions compresses unit economics. Core U.S. restaurant delivery matures faster than expected as the market saturates.

Assumptions:

Revenue CAGR 2024-2027: 14%

2027 Revenue: $16 billion

2027 EBITDA margin: 15.5%

2027 EBITDA: $2.5 billion

Exit multiple: 14x EBITDA (logistics company multiple)

The math: $2.5B × 14 = $35B EV + ~$7B net cash = ~$42B market cap. At 430M shares = ~$98, rounded to $105.

What to Watch

The thesis will evolve based on observable data. These metrics will determine which scenario materializes:

Advertising health: Watch for disclosure of advertising as a percentage of revenue. If it exceeds 10% with sustained 30%+ growth, the bull case gains credibility. If growth decelerates below 20% or conversion metrics deteriorate, the bear case becomes more likely.

New verticals unit economics: Management has described these as “improving” for years without quantification. Specific contribution margin disclosure or continued vagueness through 2026, will reveal whether the path to profitability is real.

Deliveroo EBITDA: The $45 million Q4 2025 guide and $200 million 2026 target are specific enough to track. Missing by 25%+ would signal structural problems; beating would validate international execution.

Technology platform milestones: Demand a scoreboard: feature release velocity, engineering hours per feature, time from U.S. launch to global deployment. If management can’t quantify progress, assume the rewrite is troubled.

Cohort behavior: Are mature user cohorts increasing order frequency, or plateauing? Cross-category attachment rates—the percentage of users ordering from multiple verticals—indicate whether the “local commerce platform” vision is materializing.

Regulatory spread: Monitor whether commission caps and gig worker legislation expand beyond the current ~68 jurisdictions. Movement from “handful of cities” to “majority of major metros” would fundamentally alter the risk profile.

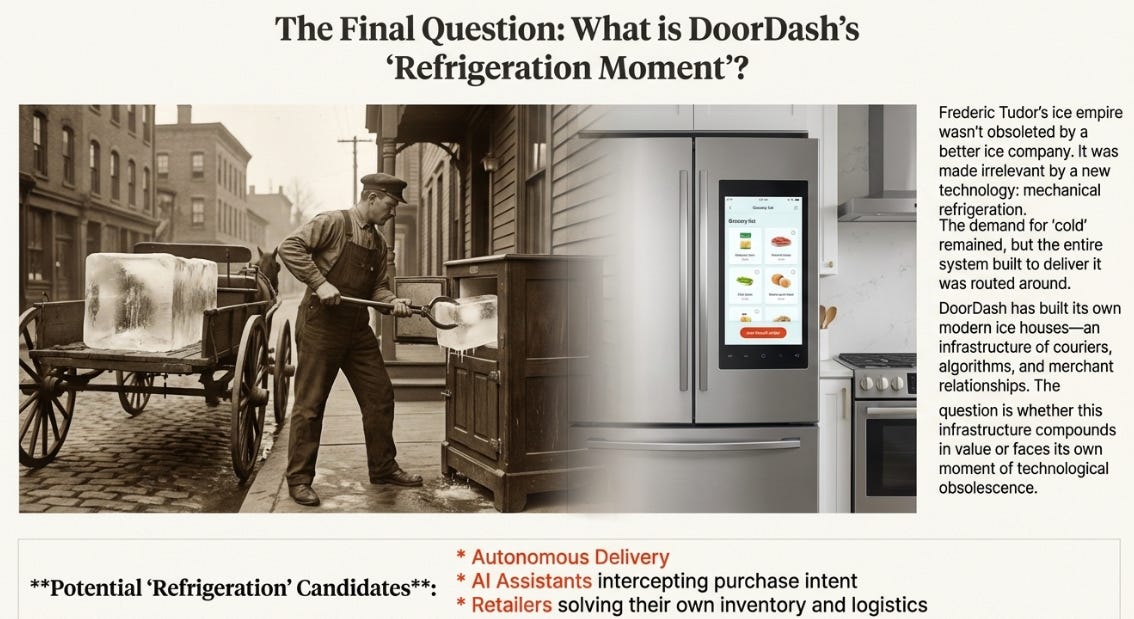

The Refrigeration Question

Frederic Tudor died wealthy in 1864, one of America’s richest men. Within two decades, mechanical refrigeration began its spread—first industrial, then commercial, eventually residential. By 1930, the natural ice trade was dead. Tudor’s ice houses weren’t obsoleted by better harvesting or faster ships. They were obsoleted by a technology that solved the underlying problem in a completely different way. The demand remained; the system didn’t.

DoorDash has built its own ice houses: couriers, algorithms, merchant integrations, consumer habits; across American suburbs and increasingly the world. The question is whether this infrastructure compounds in value or faces its own refrigeration moment.

Candidates exist. Autonomous delivery could make the Dasher network a legacy liability. AI assistants could intercept purchase intent before any app opens. Retailers could solve their inventory problems and build direct relationships. None is imminent. But the question matters: Is DoorDash building durable infrastructure, or infrastructure that will be routed around?

The market prices DoorDash as though the ice houses stand forever. At $220, you’re paying for that permanence. At $155-165, you’d be paying for the infrastructure’s value while acknowledging that nothing lasts forever.

Tudor would understand the bet. He’d probably take it. But he’d want a better price.

Disclaimer:

The content does not constitute any kind of investment or financial advice. Kindly reach out to your advisor for any investment-related advice. Please refer to the tab “Legal | Disclaimer” to read the complete disclaimer.