GE Vernova 4Q25 Earnings: The AI Boom Runs on Turbines

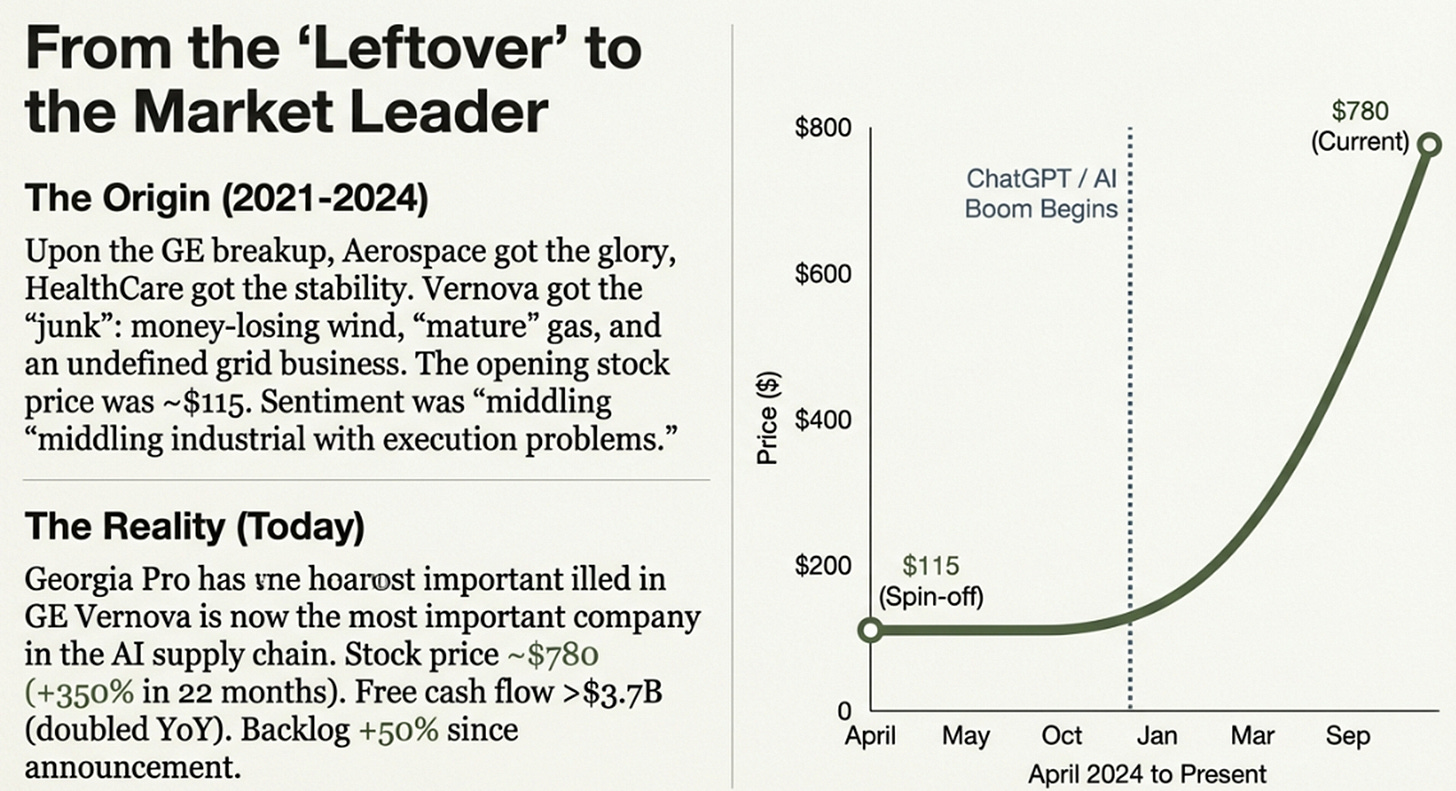

GE Vernova was the unwanted remainder of a 130-year-old breakup. Two years later, it's the most important company in the AI supply chain.

TL;DR:

AI didn’t just increase electricity demand , it changed the value of time, turning turbines and transformers into scarce capacity.

GEV is winning not on product, but on deliverability: slot reservations, deposits, and multi-year queues.

The only unresolved risk is Wind , everything else has flipped from “mature” to structurally advantaged.

On a Tuesday morning in the fall of 2021, General Electric announced it would break itself into three pieces. The details had been leaking for weeks, and Wall Street had already sorted the children into favorites.

GE Aerospace was the crown jewel, jet engines, defense contracts, a business with pricing power and barriers to entry that would make any industrial CEO weep. GE HealthCare was the reliable earner , imaging equipment, pharmaceutical diagnostics, the kind of steady margin business that pension funds love. And then there was the energy business.

The energy business was what was left.

It had money-losing wind turbines. It had legacy steam power contracts from a previous decade. It had a gas turbine division that analysts called “mature,” which is the polite way of saying they expected it to shrink. It had an electrification unit, grid equipment, transformers, switchgear , that was generating about $5 billion in annual revenue with no particular distinction. It didn’t even have a proper name yet. When GE Vernova finally began trading as an independent company in April 2024, the stock opened at roughly $115 per share. The market capitalization implied that this was a middling industrial business with some execution problems and limited upside.

Within twenty-two months, the stock would be up 350%.

The backlog would be 50% larger than the day the split was announced. The company would be generating $3.7 billion in free cash flow, more than double the prior year. And the largest, wealthiest technology companies on earth , the ones building the data centers that power artificial intelligence, would be standing in line, paying non-refundable deposits to reserve turbines they wouldn’t receive for three or four years.

This is a story about how the thing nobody wanted became the thing everybody needs. But it is also a story about something more specific: the moment when a business stops competing on its product and starts competing on time.

The Physics Problem

The conventional narrative about GE Vernova’s transformation goes like this: AI needs a lot of electricity, GEV makes the equipment that generates and delivers electricity, therefore GEV benefits from AI. This is true in the way that saying “restaurants benefit from hunger” is true. It’s correct and entirely insufficient.

What actually happened is more interesting.

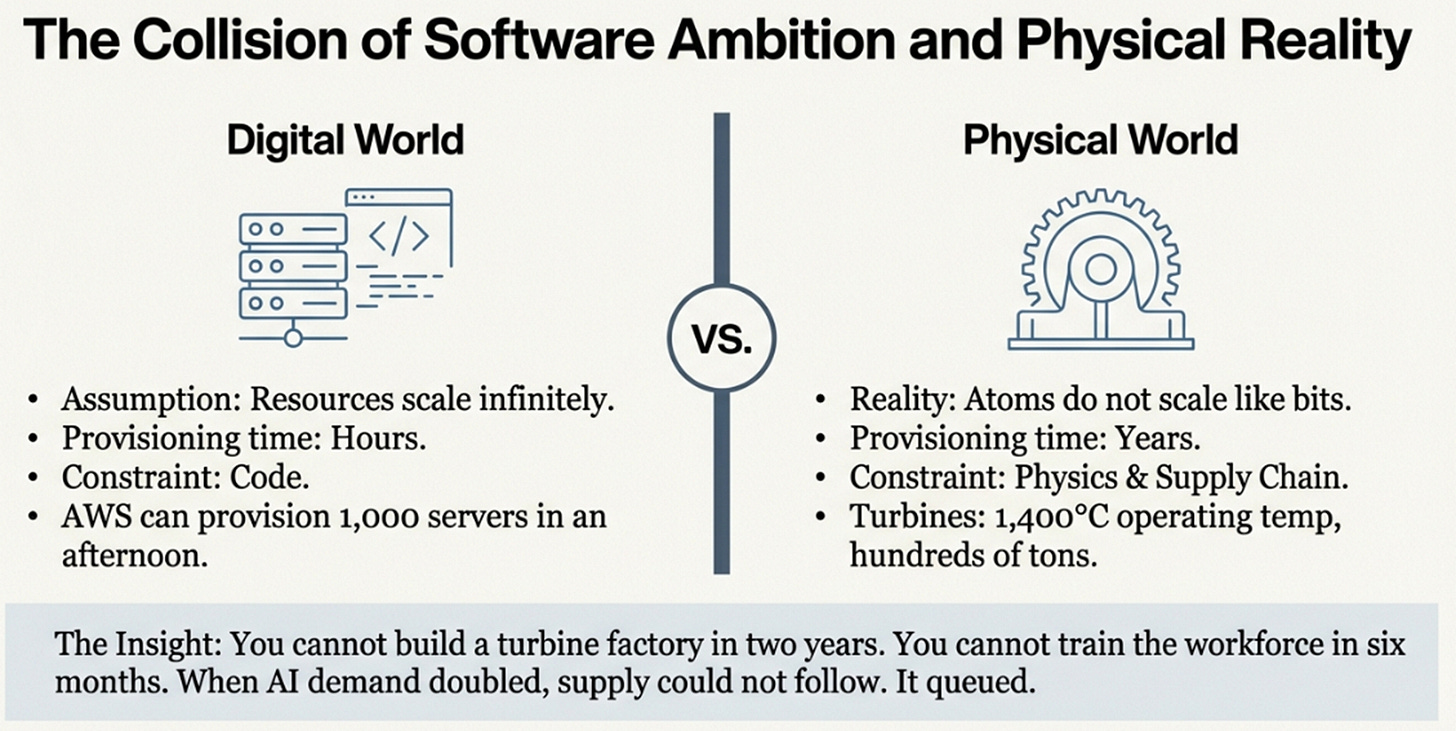

The digital economy spent two decades operating on an implicit assumption: the physical world is a solved problem. Software scales infinitely. Cloud computing scales on demand. Data storage costs trend toward zero. If you need more compute, you spin up more servers. The bottleneck is always in the code, never in the atoms.

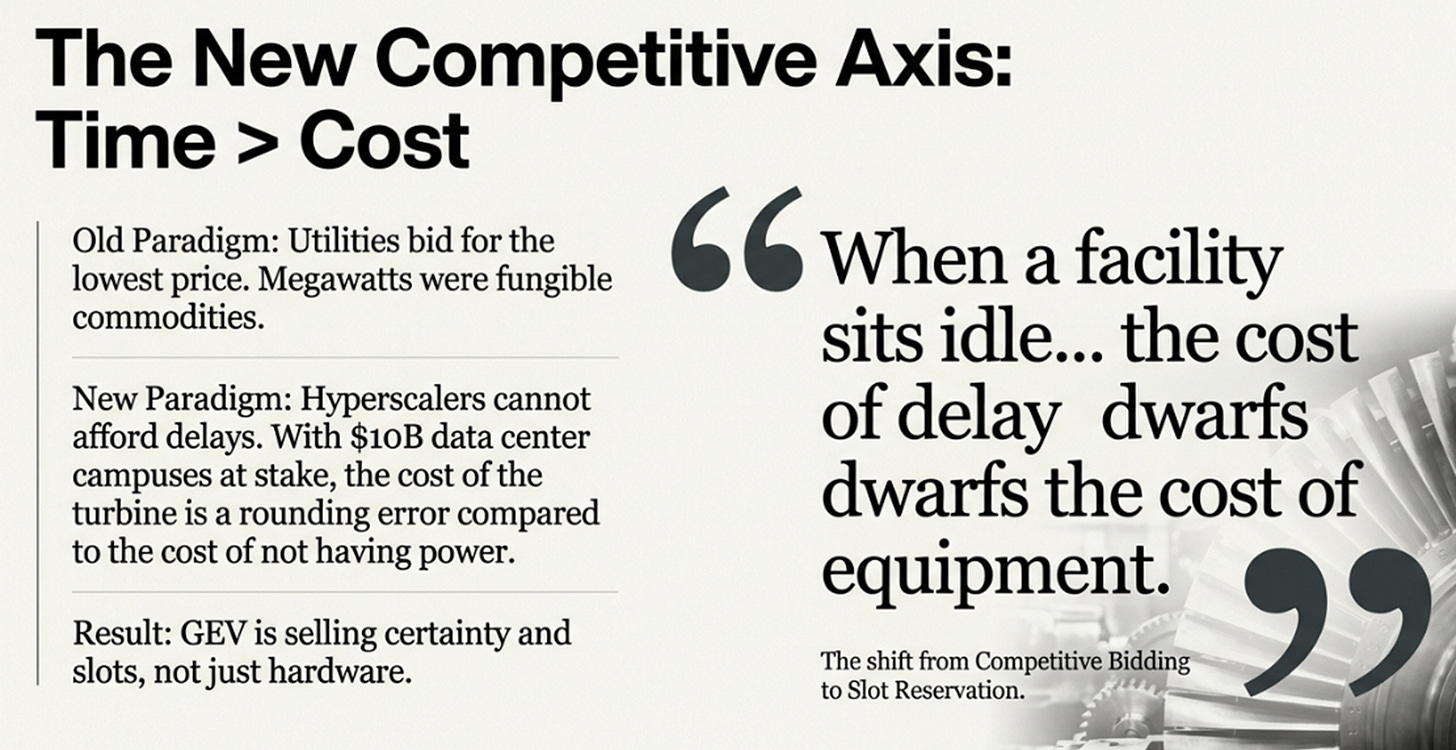

ChatGPT launched in November 2022, weeks before GE Vernova formally stood up as a separate entity. Within eighteen months, that assumption was in ruins. AI workloads didn’t just require more electricity. They required a fundamentally different kind of electricity: dense, continuous, fast-ramping, and available on a timeline measured in months, not years. A hyperscaler spending $10 billion on a new data center campus doesn’t care whether the turbine costs $50 million or $70 million. What they care about is whether the power is on when the servers arrive. When a facility sits idle because the grid connection takes three years, the cost of that delay, in lost revenue, in competitive positioning, in the AI race itself , dwarfs the cost of any piece of equipment.

This transformed the economics of the power equipment market in a way that hadn’t happened before. Historically, utility customers bought turbines on long procurement cycles with competitive bidding processes designed to minimize price. The product was megawatts, and megawatts were roughly fungible. But when the binding constraint shifted from cost to time, the entire competitive dynamic inverted. The question was no longer “who makes the best turbine?” It was “who can deliver soonest?”

GE Vernova didn’t engineer this shift. They were simply standing in the right place when it happened, with the world’s largest installed fleet of gas turbines, a global services network, and manufacturing capacity that couldn’t be replicated on any relevant timeline. The moat wasn’t technology. It was physics: you cannot build a turbine factory in two years, you cannot train the workforce in six months, and you cannot accelerate the supply chain for specialized alloys and castings by wishing it were faster.

This is the part that software-trained investors consistently underestimate. In the digital world, supply responds to demand almost instantly. AWS can provision a thousand servers in an afternoon. But a heavy-duty gas turbine is a physical object that weighs hundreds of tons, operates at temperatures above 1,400 degrees Celsius, and requires precision engineering measured in thousandths of an inch. The factories that produce these machines were built over decades. The workers who assemble them require years of training. The nickel superalloys in the hot gas path come from a small number of specialized foundries. None of this can be parallelized or accelerated in the way that software deployment can. When demand doubles, supply doesn’t follow , it queues.

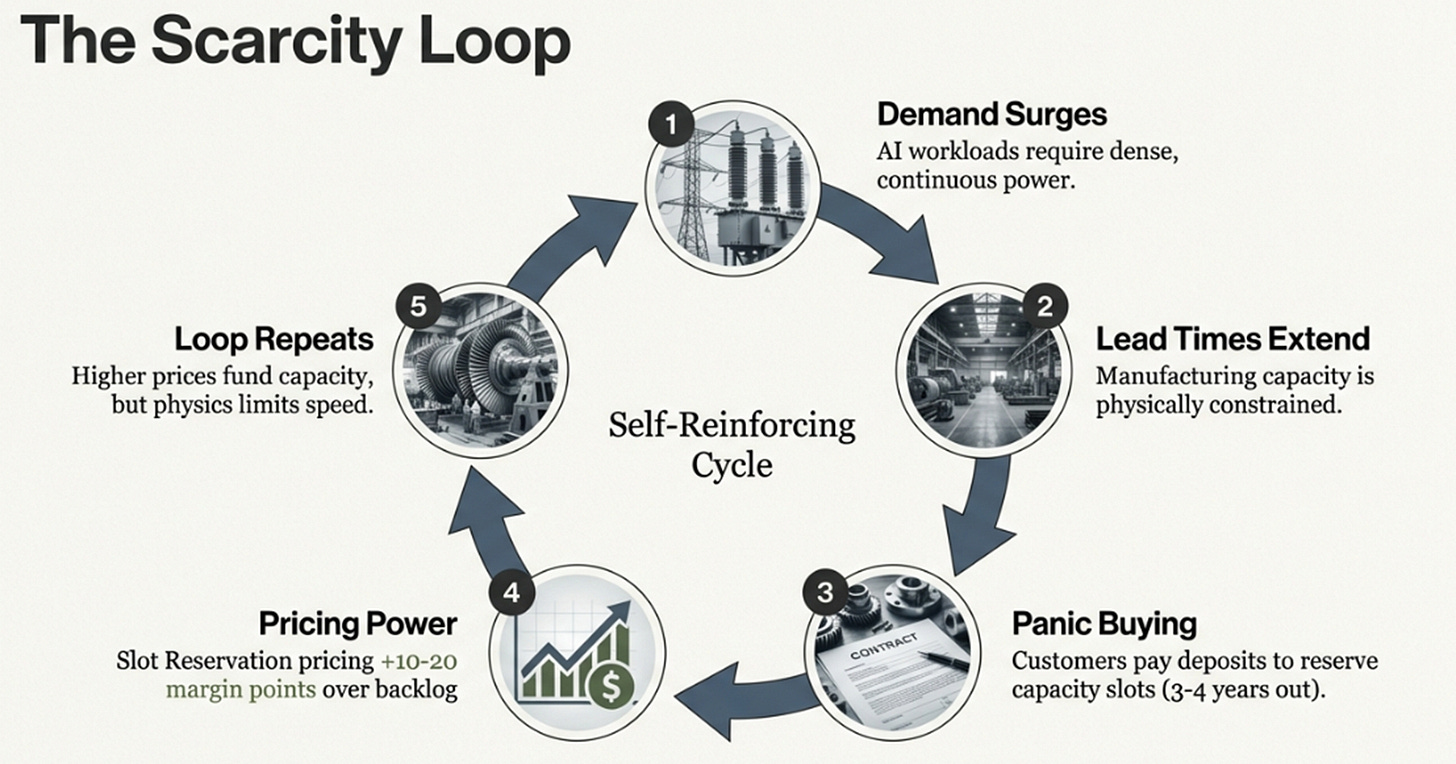

The result is what I’d call a scarcity loop. As demand surges, lead times extend. As lead times extend, customers reserve capacity further into the future. As reservations fill, lead times extend again. Each turn of the loop increases the pricing power of whoever controls the capacity. And the loop is self-reinforcing , right up until the moment demand breaks.

How Every Concern Got Answered (Except One)

It is worth pausing on how thoroughly GE Vernova addressed the worries the market had at its birth, because the speed of the resolution is itself part of the story.

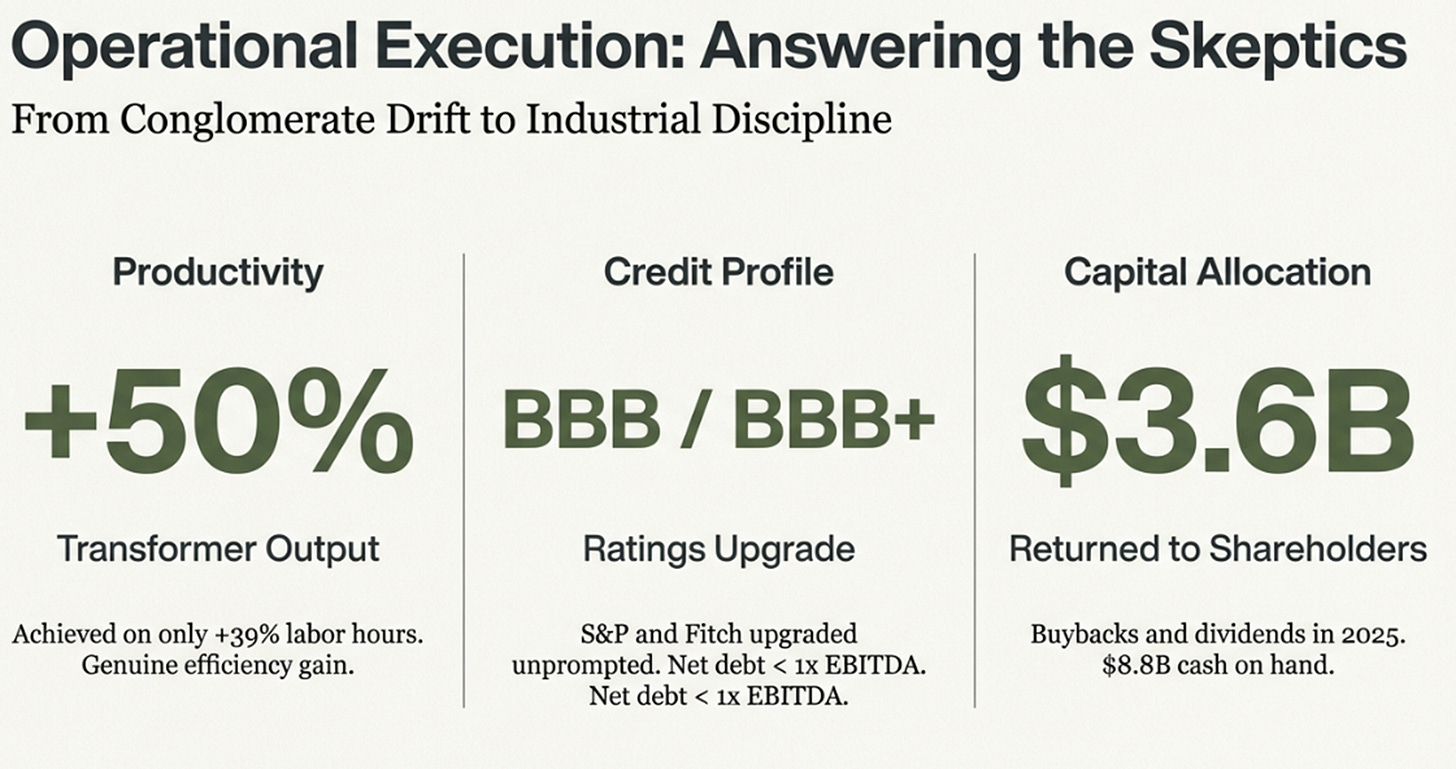

The first concern was execution credibility. This was, after all, a business that had spent two decades inside a conglomerate famous for financial engineering and operational neglect. Could the management team actually run a focused industrial company? The answer came in the operating data: transformer production output rose 50% in the fourth quarter of 2025 on only 39% more labor hours. That’s not growth, that’s genuine productivity improvement. Both S&P and Fitch upgraded the company’s credit rating in the quarter, to BBB and BBB+ respectively, both with positive outlooks. When credit agencies upgrade you unprompted, the execution question is settled.

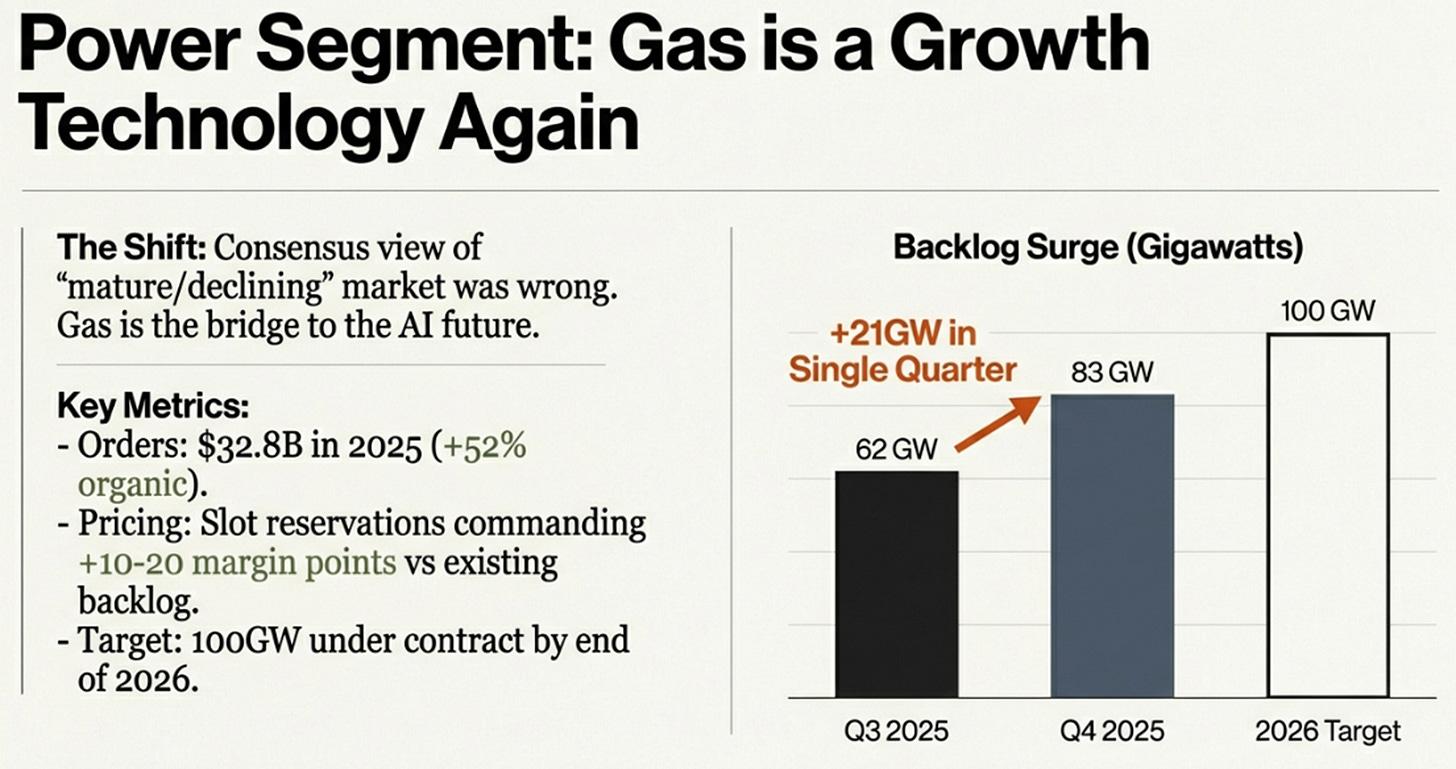

The second concern was that gas power was a mature, declining market. This was the consensus view as recently as 2023. It is now almost comically wrong. In 2025, GE Vernova booked $32.8 billion in Power segment orders, up 52% organically. Gas power equipment backlog and slot reservation agreements surged from 62 gigawatts to 83 gigawatts in a single quarter, the fourth quarter of 2025 , with CEO Scott Strazik projecting 100 gigawatts under contract by the end of 2026. On the earnings call, Strazik disclosed that pricing on slot reservation agreements is running “10 to 20 points” above existing backlog. Those are margin points, not percentage points. The pricing environment isn’t just strong. It’s accelerating.

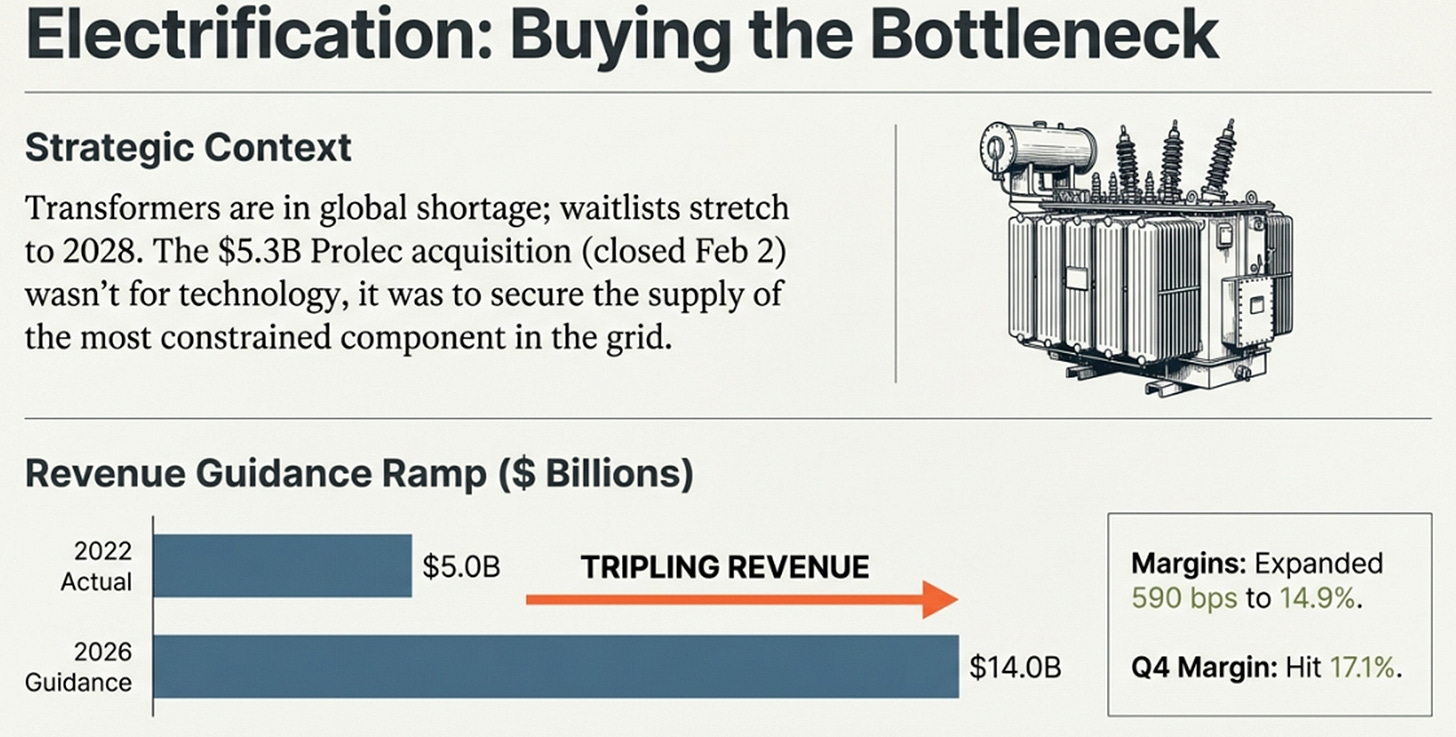

The third concern was that Electrification was an afterthought , a small, undifferentiated business lost inside a conglomerate. In 2022, the segment generated about $5 billion in revenue. Management is now guiding to $13.5 to $14.0 billion for 2026, including approximately $3 billion from the Prolec GE acquisition that closed on February 2. That’s nearly a tripling in four years. The fourth quarter was the segment’s largest order quarter in its history , $7.4 billion, with a book-to-bill ratio of 2.5 times. Margins expanded 590 basis points for the full year to 14.9%, and hit 17.1% in the fourth quarter, already within next year’s guidance range of 17 to 19%.

The Prolec acquisition deserves specific attention because it reveals how management thinks about the business. Transformers are in global shortage. They take years to manufacture. The waiting list for a large power transformer in North America now stretches beyond 2028. Prolec is one of the largest transformer producers in the Americas. GE Vernova paid $5.3 billion not to enter a new market or acquire a new technology but to secure supply of the component that is most constrained in the grid buildout. When you buy the bottleneck, you don’t need to outperform on product. You need to deliver on time. The same logic that governs gas turbines , urgency over optimization, applies to transformers. And there’s a quieter development that hasn’t received any analyst attention: the company’s solid-state transformer program produced its first unit in January 2026, with testing planned for this summer and delivery to a hyperscaler customer in autumn. If that program scales, it represents an entirely new product category. If it doesn’t, nothing in the current financial guidance depends on it. It is pure optionality sitting inside a business the market is already undervaluing.

The fourth concern was capital discipline. The balance sheet answered it: $8.8 billion in cash, $3.6 billion returned to shareholders in 2025 through buybacks and dividends, the quarterly dividend doubled from $0.25 to $0.50, and the share repurchase authorization raised from $6 billion to $10 billion. The company will issue approximately $2.6 billion in debt for the Prolec acquisition and remain below one times gross debt-to-EBITDA. That is a conservative posture by any standard.

And then there is the one concern that wasn’t resolved. The one that got worse.

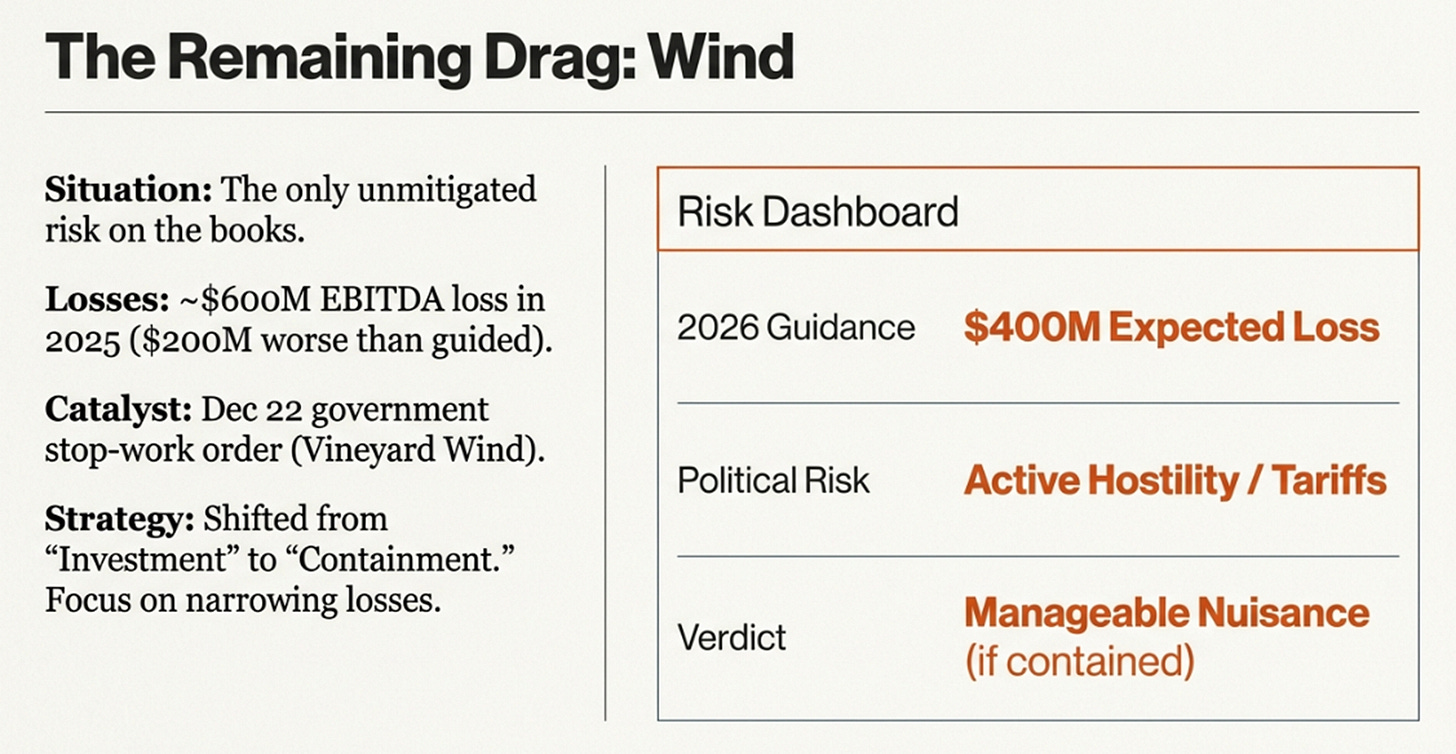

Wind posted approximately $600 million in EBITDA losses for 2025 , $200 million worse than management had guided just seven weeks earlier at the December 9 investor day. The deterioration was driven by the U.S. government’s December 22 stop-work order on all offshore wind activity, which forced GE Vernova to accrue incremental losses on the Vineyard Wind project. The fourth-quarter Wind EBITDA loss of $225 million compared to consensus expectations of roughly $40 million. Revenue fell 25% YoY. If the installation vessel window closes at the end of March without the remaining turbines completed, 2026 Wind revenue faces an additional $250 million hit.

Strazik’s language on the call was revealing. “Focused on what we can control.” That’s not the language of investment. That’s the language of containment. Management guides to approximately $400 million in Wind EBITDA losses for 2026, with losses concentrated in the first half, $300 to $400 million in the first two quarters alone, partially offset by profitability in the second half. The 2028 target of 6% Wind EBITDA margin requires over 1,200 basis points of improvement in a segment facing active political hostility from the current administration. International onshore orders showed some life in the fourth quarter, up 53% YoY , but U.S. onshore remains impaired by permitting delays and tariff uncertainty.

The honest question isn’t whether Wind can be fixed. It’s whether GE Vernova should be spending any attention on it while its two other segments are compounding at these rates. Wind consumed roughly $600 million in EBITDA in 2025 and an unknowable amount of management bandwidth , bandwidth that could have gone to accelerating the gas ramp or scaling Electrification. The market has largely priced Wind as a tolerable drag that narrows over time. That assumption may prove correct. But the segment has surprised to the downside three times in twelve months, and the political risk is binary in a way that financial models cannot capture. Nobody modeled a stop-work order on December 22.

What $210 Billion Requires

The fourth quarter itself can be covered briefly, because the reader now has the context to interpret it.

Revenue of $11.0 billion beat the consensus estimate of $10.3 billion. Adjusted EBITDA of $1.16 billion missed the estimate of $1.25 billion , entirely attributable to Wind. GAAP earnings per share of $13.39 obliterated the $3.18 estimate, but that number is meaningless: it includes a $2.9 billion one-time tax benefit from a valuation allowance release. The “clean” result, Power margins of 16.9%, Electrification margins of 17.1%, $8 billion in equipment backlog margin dollars added over the full year, more than the prior two years combined , is what matters. Management raised 2026 guidance to $44 to $45 billion in revenue and $5.0 to $5.5 billion in free cash flow. The stock traded to new all-time highs near $780.

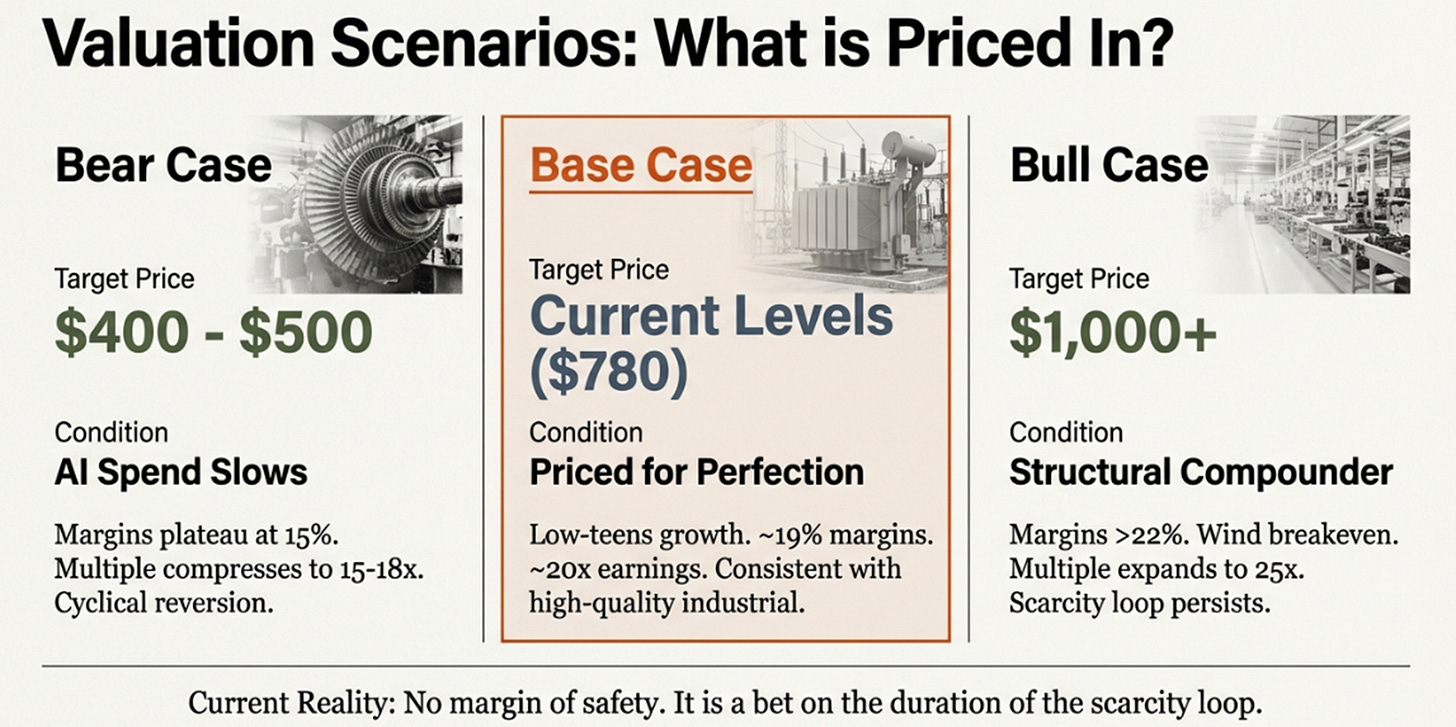

Now the harder question: what does $780 per share , roughly $210 billion in market capitalization, require you to believe?

The consensus view is mostly right: GEV is a gas turbine and grid equipment beneficiary of AI-driven power demand. The backlog is enormous. The demand is real. Wind is a drag but manageable. This view is approximately correct, and it’s why the stock is where it is.

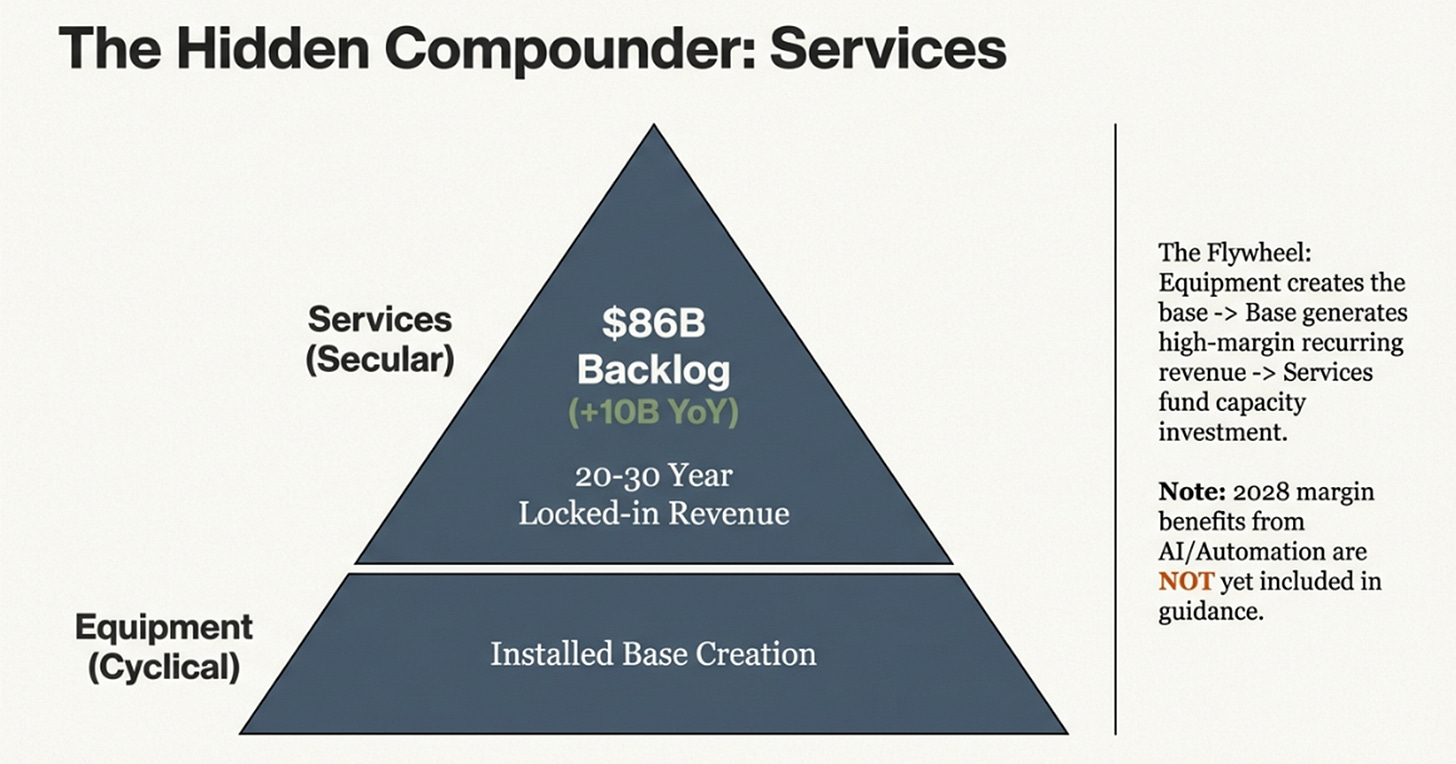

What the consensus misses is the nature of the revenue building inside the backlog. The market prices GEV as a cyclical industrial that happens to have a large order book. But the underlying business is becoming structurally more recurring with every turbine installed. The $86 billion services backlog, up $10 billion in a year, barely discussed on the call or in analyst commentary,represents decades of locked-in, high-margin maintenance and optimization revenue. Every new gas turbine creates a 20-to-30-year service relationship. And because equipment pricing is accelerating, the associated services pricing follows. This is the compounding mechanism hiding inside the quarterly results: equipment creates the installed base, the installed base generates decades of recurring services revenue, services fund the capacity investment that enables more equipment sales. Strazik noted that AI and automation benefits will become “a bigger part of margin expansion in 2028” and then added, almost casually, that these benefits are not included in the 2028 outlook. The 20% EBITDA margin target may be sandbagged.

Still, let’s be specific about what the stock assumes under different outcomes. Under what I’d call the base case , revenue growing at a low-teens compound rate to roughly $56 billion by 2028, EBITDA margins reaching 18 to 19% (just shy of the target, reflecting ongoing Wind drag and Prolec integration friction), and earnings per share of $27 to $30, the stock trades at approximately 20 to 22 times forward earnings. That’s consistent with a high-quality industrial compounder. The stock does very little from here because the market has already priced most of this.

The bull case requires the services flywheel and AI/automation benefits to push margins to 21 or 22%, Electrification to sustain 20%+ organic growth, and Wind to reach breakeven or be exited. Revenue exceeds $58 billion. Earnings per share reach the mid-$30s. The market recognizes the recurring revenue quality and re-rates toward 25 times earnings. The stock reaches $1,000 to $1,200 in three years. This requires that hyperscaler capital expenditure plans hold through 2028, the gas production ramp executes on schedule starting in the third quarter of 2026, and no major policy disruption materializes.

The bear case is simpler: the AI capital spending cycle decelerates in 2027 as model efficiency improvements reduce the rate of power demand growth. Gas orders slow. Some slot reservations are renegotiated or deferred. Margins plateau at 14 to 16% as cost inflation and lower volumes offset pricing gains. The multiple compresses to 15 to 18 times as the market reverts to pricing GEV as the cyclical industrial it was assumed to be at the spin-off. The stock trades back to $400 to $550. This doesn’t require a disaster , just a normalization. Just the market remembering that power equipment companies have historically been cyclical, and that the last time everyone was convinced a demand cycle was “structural,” it wasn’t.

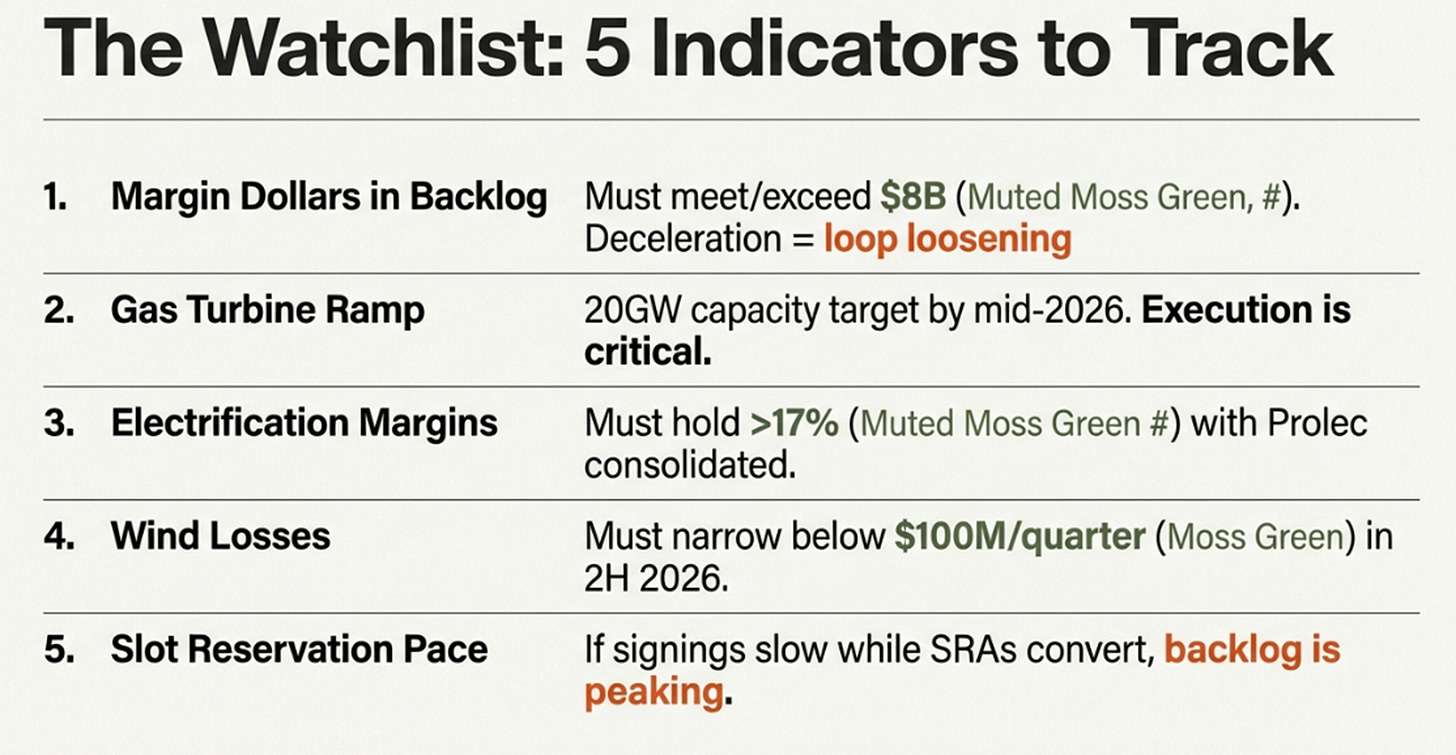

Five things will tell you, quarter by quarter, which scenario is playing out. First, equipment margin dollars added to backlog , $8 billion was the 2025 figure, and management guided to “at least as much” in 2026; any deceleration is the earliest warning sign that the scarcity loop is loosening. Second, gas turbine shipments beginning in the third quarter of 2026 , the company invested in 200 new machines and over 1,000 production workers in 2025, targeting roughly 20 gigawatts of annual capacity by mid-year; if the ramp stumbles, the margin inflection pushes to 2027. Third, Electrification EBITDA margins with Prolec consolidated , they must hold above 17% from the first quarter of 2026 to prove the acquisition is accretive, not dilutive. Fourth, Wind EBITDA in the second half of 2026 , do losses narrow below $100 million per quarter as guided, or does another offshore surprise reset expectations for the third time in twelve months? Fifth, the pace of new slot reservation agreements , if signings decelerate while existing SRAs convert to orders, the backlog may be peaking rather than compounding. That’s the difference between a cycle and a franchise.

What Was Left

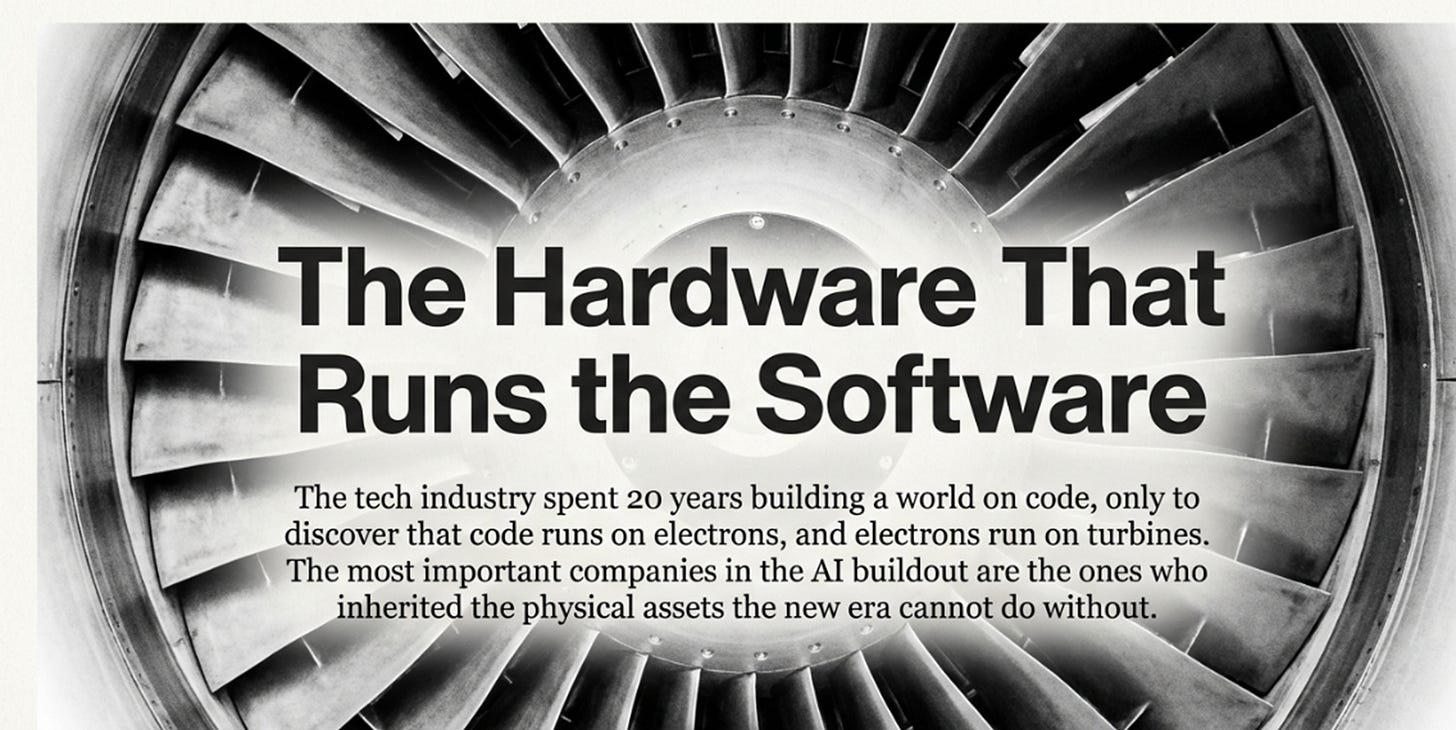

GE Vernova was what remained after a 130-year-old conglomerate gave away its best parts. The jet engines went one way. The medical equipment went another. What was left was the business that makes electricity and moves it from one place to another.

It turned out that was the thing everything else depends on.

The digital economy built its entire architecture on the assumption that physical resources, power, cooling, transmission capacity , would simply be there when needed, like oxygen. AI broke that assumption. It revealed that the binding constraint on the most important technology of the era isn’t software or semiconductors or data. It’s electrons. And the companies that produce and deliver those electrons can’t be replicated, disrupted, or scaled on a software timeline. They can only be waited for.

GE Vernova is not a technology company. It is not particularly innovative or exciting. It does not have a charismatic founder or a consumer brand or a viral product. What it is, is necessary, in a way that is hard to substitute and impossible to rush. The scarcity loop that now defines its business, demand extending lead times, lead times increasing pricing power, pricing power funding capacity that fills with the next wave of demand , is the most powerful competitive dynamic in the industrial economy right now. It won’t last forever. Scarcity loops break when demand slows or supply catches up. But the $150 billion backlog, the services contracts measured in decades, and the grid hardware shortage that will persist well into the next decade all suggest the loop has years left to run.

Whether the stock at $780 already reflects this is a separate question, and a legitimate one. The trailing multiples look absurd. The 2028 multiples look reasonable. Everything in between requires faith in execution and the durability of a demand cycle that is, by historical standards, without precedent. There is no margin of safety at this price. There is only a bet on duration, on how long the world’s hunger for electricity continues to exceed the world’s ability to deliver it.

But here is what I keep coming back to: on November 9, 2021, when GE announced its breakup, the energy business was the leftover, the piece the market valued least and understood worst. The analysts who covered GE spent their time on jet engines and MRI machines. The energy business was an afterthought, a legacy, a problem to be managed rather than a franchise to be valued. Four years later, it is the piece that the AI economy cannot function without.

There is a lesson in this that extends beyond one company. The technology industry has spent two decades building a world that runs on software, and then discovered , rather suddenly, that software runs on hardware, and hardware runs on electricity, and electricity runs on turbines and transformers and transmission lines that take years to build and decades to replace. The most important companies in the next phase of the AI buildout may not be the ones writing the models. They may be the ones that were left behind by the last era and inherited, almost by accident, the physical assets that the new era cannot do without.

Sometimes the most important business is the one nobody thinks to value until they need it. By then, the price of urgency has already been set , and the company that sells it gets to name the terms.

Disclaimer:

The content does not constitute any kind of investment or financial advice. Kindly reach out to your advisor for any investment-related advice. Please refer to the tab “Legal | Disclaimer” to read the complete disclaimer.