How Regulation Forced Alibaba's Evolution

A platform once punished for its power is now protected by infrastructure—and Jack Ma learned Carnegie’s lesson the hard way

TLDR:

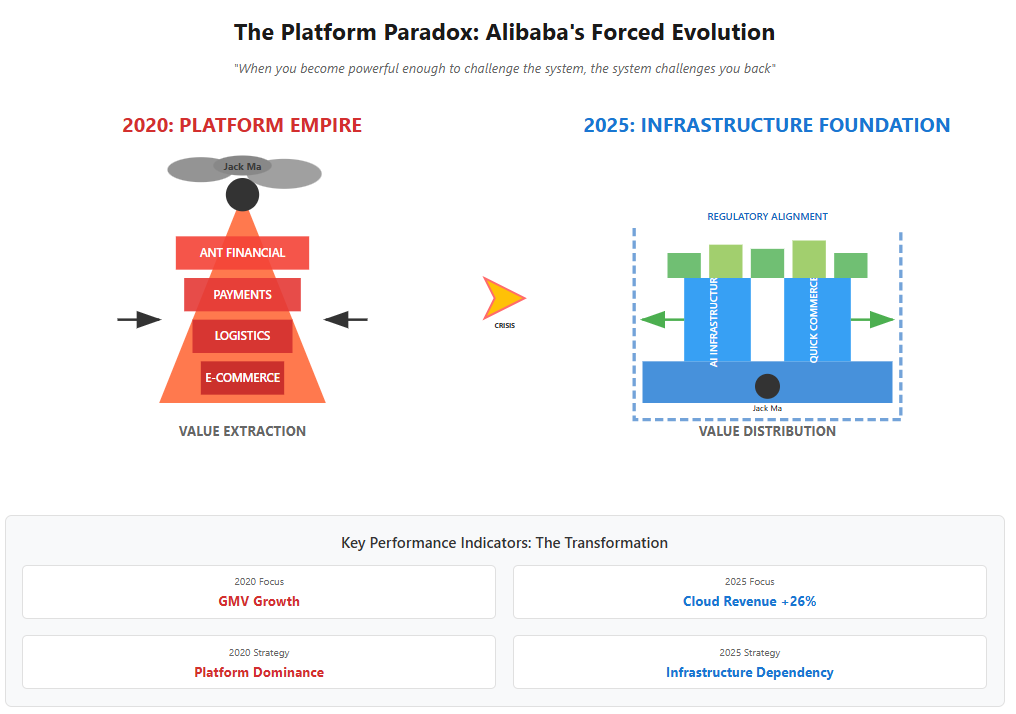

Regulation Didn't Kill Alibaba—It Rewired It: Jack Ma’s infamous 2020 speech triggered a regulatory crackdown that dismantled Alibaba’s platform empire—but also catalyzed its evolution into politically-aligned infrastructure.

From Platform Dominance to Infrastructure Dependency: Alibaba’s new strategy centers on two pillars—AI infrastructure (via open-sourced LLMs + embedded agents) and Quick Commerce (daily touchpoints + data loops)—creating defensible scale and state-sanctioned relevance.

Political Risk Became a Strategic Moat: The company that once challenged the system now strengthens it—making Alibaba not just investable again, but one of the most misunderstood transformation stories in global tech.

In 1901, the most powerful man in America wasn't the President—it was J.P. Morgan. When Morgan orchestrated the creation of U.S. Steel, combining Carnegie's empire with a dozen smaller companies, he created the world's first billion-dollar corporation. Andrew Carnegie, the Scottish immigrant who had built America's steel infrastructure, walked away with $480 million—roughly $15 billion in today's money.

But Carnegie understood something that many industrialists of his era missed: there comes a moment when continued expansion becomes politically unsustainable, when the very success that built an empire becomes the threat that could destroy it. Rather than fight the inevitable regulatory backlash, Carnegie sold at the peak and spent his remaining years as a philanthropist, building libraries and universities. He transformed from robber baron to beloved benefactor, securing a legacy that outlasted his corporate empire.

Jack Ma never read that particular lesson from history. But on October 24, 2020, he learned it anyway.

The Rise: Building the Everything Empire

To understand Alibaba's fall and resurrection, you have to appreciate how high Jack Ma had climbed—and how far he had to fall.

By 2020, Ma had built something unprecedented in Chinese business history: a true platform empire that touched nearly every aspect of Chinese digital life. Alibaba wasn't just an e-commerce company—it was the infrastructure of Chinese capitalism itself. Taobao and Tmall handled more transactions than Amazon and eBay combined. Alipay processed more mobile payments than Visa and Mastercard. Cainiao moved more packages than FedEx. Ant Group was preparing to become the world's most valuable financial services company.

Ma's vision was breathtaking in its scope. He spoke of creating an "economic body" that would serve 2 billion consumers globally, help 10 million businesses make money, and create 100 million jobs. Alibaba wasn't just connecting buyers and sellers—it was building the nervous system for 21st-century commerce.

The numbers told the story of unprecedented success. Alibaba's ecosystem processed over $1 trillion in gross merchandise volume annually. The company's market capitalization peaked above $850 billion, making it one of the world's most valuable corporations. Ma himself became China's richest person, a folk hero who represented the possibility of entrepreneurial success in the world's largest authoritarian state.

Like the railroad barons of America's Gilded Age, Ma had built his empire by solving genuine problems. Chinese merchants needed access to customers; Chinese consumers needed access to goods; the Chinese economy needed digital infrastructure. Alibaba solved all three problems simultaneously, creating network effects that made the platform more valuable with every new participant.

But also like those railroad barons, Ma's success created the conditions for his own downfall.

The Speech That Changed Everything

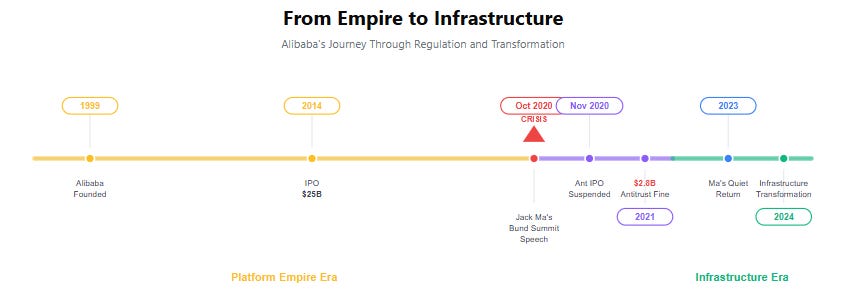

On October 24, 2020, Ma stood before China's financial establishment at the Bund Summit in Shanghai. Ant Group's IPO—set to raise $37 billion and become the largest public offering in history—was scheduled for just days later. Ma was at the absolute peak of his power, about to crown his career with the ultimate validation from global capital markets.

Instead, he delivered what would become his political suicide note.

"Good innovation is not afraid of regulation," Ma declared to an audience filled with China's banking regulators, "but we are afraid of outdated regulation." He compared global financial rules to an "old people's club" and suggested that traditional banks were pawns in a system that stifled innovation. The Basel Accords—international banking regulations developed after the 2008 financial crisis—were, in Ma's view, irrelevant to the digital financial services that Ant Group was pioneering.

The speech was vintage Jack Ma: bold, visionary, slightly arrogant. It was the same confidence that had built Alibaba from a startup in his apartment to a global empire. But it was also a fundamental misreading of the political moment.

Ma had forgotten Andrew Carnegie's lesson: when you become powerful enough to challenge the system, the system challenges you back.

The response was swift and merciless. Thirty-six hours later, Chinese regulators suspended Ant's IPO. Six months after that, Alibaba received a $2.8 billion antitrust fine—the largest in Chinese corporate history. Ma himself disappeared from public view for three months, canceling television appearances and stepping back from the company he had built.

More than just punishment, this was a system-level correction. The Chinese government was sending a clear message: no company, regardless of its success or global stature, could position itself as more powerful than the state.

The Wilderness Years: A Company Adrift

What followed was perhaps the most challenging period in Alibaba's history—not because of the financial penalties, but because the company had lost its North Star.

For two decades, Alibaba's strategy had been simple: expand into every adjacent market, leverage network effects to dominate each vertical, and use data from one business to strengthen all the others. The company had grown from e-commerce into payments, from payments into lending, from lending into wealth management, from wealth management into insurance. Each expansion made the ecosystem stronger and more defensible.

But the regulatory reckoning ended that playbook permanently. Exclusive merchant agreements were banned, reducing Alibaba's ability to lock in supply. Financial services expansion was curtailed, eliminating a massive growth opportunity. Platform fees and data usage faced new scrutiny, threatening core revenue streams.

Most importantly, Jack Ma's absence left a leadership vacuum at the worst possible time. Ma had been more than just Alibaba's founder—he was its strategic visionary, cultural icon, and political navigator. His charisma had smoothed relationships with government officials, inspired employees through difficult periods, and convinced global investors to believe in Chinese innovation.

Without Ma, Alibaba seemed to lose its sense of purpose. The company's stock price fell from its 2020 peaks, declining more than 70% over the following months. Quarterly earnings calls became exercises in damage control rather than growth strategy sessions. Morale inside the company reportedly plummeted as employees wondered whether Alibaba's best days were behind it.

The comparison to IBM in the early 1990s is instructive. Like Alibaba after 2020, IBM had been the dominant force in its industry for decades before facing an existential crisis that threatened its core business model. The company that had defined computing for a generation suddenly seemed outdated and directionless, struggling to adapt to a world that had moved beyond its original vision.

But IBM's story didn't end there—and neither would Alibaba's.

The Quiet Return: Rehabilitation and Renewal

Jack Ma's public rehabilitation began not with grand gestures, but with quiet competence.

In early 2023, Ma surfaced at a school opening ceremony in his hometown of Hangzhou. No speeches about disrupting global finance. No bold predictions about the future of technology. Instead, he spoke about education, community development, and the importance of serving society. The message was clear: the combative entrepreneur who had challenged regulators was gone, replaced by a more reflective leader focused on social contribution.

But Ma's return coincided with something more significant: a fundamental shift in how the Chinese government viewed technological infrastructure. By 2023, U.S.-China tech competition had intensified to the point where AI capabilities became a national security priority. Beijing needed domestic champions in cloud computing and artificial intelligence—not as threats to state power, but as extensions of it.

This timing explains why Alibaba's transformation succeeded where earlier attempts had failed. The company's previous diversification efforts in 2021-2022 looked like desperate expansion into whatever markets remained available. The infrastructure pivot that began in 2023 aligned perfectly with what the government wanted: technological capabilities that strengthened rather than threatened state objectives.

Around the same time, Alibaba began signaling a fundamental strategic pivot. The company wasn't just complying with new regulations—it was embracing them, using regulatory guidance as a framework for building a more sustainable business model that served national priorities rather than shareholder returns alone.

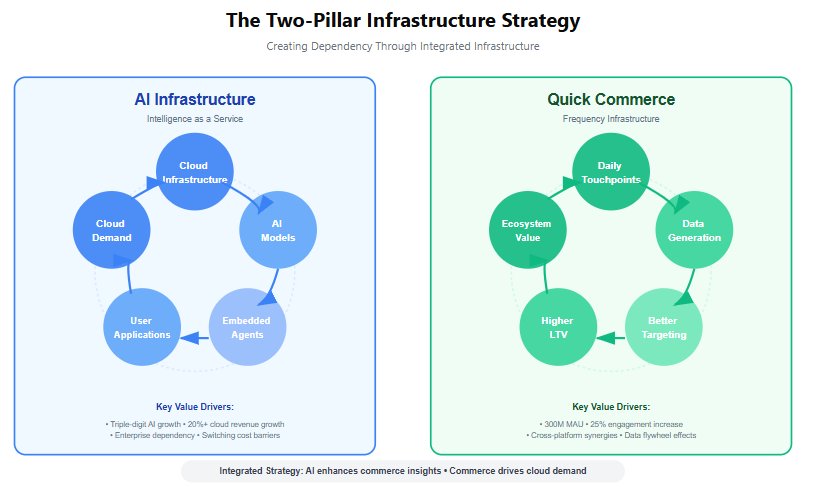

This shift has two pillars, both designed to create dependency rather than dominance, and both structured to be exceptionally difficult for competitors to replicate.

The Intelligence Infrastructure

The first pillar is AI and cloud computing, but not as a competitor to ChatGPT or Amazon Web Services. Instead, Alibaba is building the infrastructure that AI applications run on while embedding AI agents directly into platforms people already use.

The distribution advantage is the key competitive moat. While Baidu builds standalone AI models and ByteDance experiments with AI features, Alibaba places AI agents inside Taobao (for shopping assistance), DingTalk (for workplace productivity), and Amap (for navigation and local services). These aren't competing with external AI services—they're creating demand for the cloud infrastructure that runs the models behind the scenes.

This approach creates switching costs competitors struggle to match. Tencent could build similar AI capabilities, but lacks the commerce platform where AI agents prove most valuable to businesses. ByteDance has distribution through TikTok, but doesn't control the underlying cloud infrastructure where AI models run. Baidu has strong AI research, but limited access to the daily usage patterns that improve models through real-world feedback.

The business model creates a closed loop: AI-powered features drive usage, usage generates demand for cloud computing, cloud revenue funds better AI models, better models enable more sophisticated features. Alibaba controls both the distribution (the apps) and the infrastructure (the cloud), creating dependency rather than competition.

The numbers tell the story of network effects reaching critical mass. Cloud intelligence revenue accelerated from 13% to 18% to 26% growth over consecutive quarters through 2024. AI-related products maintained triple-digit growth for eight straight quarters as of Q3 2024. Most telling, external cloud revenue—the portion that comes from other companies rather than Alibaba's internal usage—grew consistently above 20% annually as Chinese businesses increasingly depend on Alibaba's AI infrastructure.

Enterprise adoption metrics validate the dependency thesis. Major partnerships, including a recent integration with SAP, demonstrate that enterprises are embedding Alibaba's AI capabilities directly into their core business processes. Once integrated, switching costs become prohibitive—migrating AI workflows, retraining models on new infrastructure, and rebuilding data pipelines creates the kind of dependency that infrastructure providers dream of.

The Frequency Infrastructure

The second pillar transforms how Alibaba thinks about commerce itself, and it's structured to be nearly impossible for competitors to replicate at scale. Quick Commerce—instant delivery of everything from groceries to electronics—represents a fundamental shift from occasional, high-value transactions to frequent, low-value interactions that create daily dependency.

The strategy works because it solves the fundamental weakness in Meituan's business model while leveraging Alibaba's unique advantages. Meituan dominates food delivery but struggles to expand beyond restaurants because it lacks the merchant relationships and logistics infrastructure for general commerce. Alibaba has both—millions of merchants already selling on Taobao and Tmall, plus Cainiao's established delivery network.

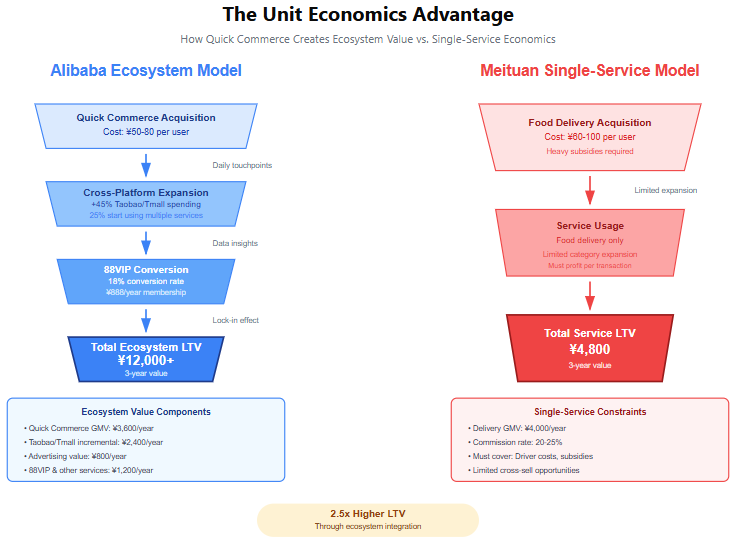

More importantly, Alibaba doesn't need Quick Commerce to be profitable as a standalone business. Meituan must extract margin from every delivery to justify its existence. Alibaba can use Quick Commerce as customer acquisition and engagement infrastructure that pays for itself through higher advertising revenue and cross-platform spending across its ecosystem.

The unit economics reflect this strategic difference. While Meituan needs positive margins per delivery, Alibaba measures success by total customer lifetime value across all platforms. A Quick Commerce customer who generates modest delivery profits but spends significantly more on Taobao advertising or becomes an 88VIP member creates overall ecosystem value that pure-play competitors can't match.

The data flywheel amplifies this advantage. Every Quick Commerce interaction generates behavioral data that improves product recommendations, advertising targeting, and merchant tools across all Alibaba platforms. That data feeds back into traditional e-commerce, creating a competitive advantage that grows stronger with each additional user—something Meituan's single-use case model cannot replicate.

The early results validate the strategic logic and address the sustainability question that critics raise. Quick Commerce approaches 300 million monthly active users as of Q3 2024 and contributed to a 25% increase in overall Taobao app engagement. More significantly, 88VIP membership—Alibaba's loyalty program that integrates all services—has grown to over 53 million members, representing the most valuable and engaged customers across the entire ecosystem.

But the real validation comes from unit economics improvement. Delivery costs per order have declined consistently as density improves in major cities, while average order values expand as consumers use the service for broader product categories beyond food. The service doesn't need to achieve Amazon-level logistics margins to succeed—it just needs to break even while driving incremental value across the broader ecosystem.

This addresses the core sustainability challenge: how does Alibaba maintain competitive advantages as markets mature? The answer lies in the integration effects that strengthen over time. As more consumers use Quick Commerce, the data quality improves for all Alibaba platforms. As more merchants adopt Alibaba's AI tools, the switching costs increase. As more developers build on Alibaba's cloud infrastructure, the network effects become more defensive.

The New Compact: Serving the State

The most profound change in Alibaba's transformation isn't operational—it's philosophical. The company that once positioned itself as disrupting traditional systems now presents itself as strengthening China's technological foundation.

This shift reflects a sophisticated understanding of political economy that Jack Ma seemed to lack during his 2020 speech. The old Alibaba succeeded by concentrating market power; the new Alibaba succeeds by distributing capability. The old model made Alibaba indispensable but politically vulnerable; the new model makes Alibaba essential and politically protected.

The AI infrastructure supports Chinese technological independence at a moment when U.S.-China tech competition has become a national security priority. The Quick Commerce network improves economic efficiency for millions of small businesses. The integrated platform makes Chinese commerce more competitive globally while keeping data and capabilities within Chinese sovereignty.

These outcomes align perfectly with Beijing's strategic objectives. Rather than fighting state power, Alibaba now amplifies it. The AI infrastructure supports Chinese technological independence at a moment when U.S.-China tech competition has become a national security priority. The Quick Commerce network improves economic efficiency for millions of small businesses. The integrated platform makes Chinese commerce more competitive globally while keeping data and capabilities within Chinese sovereignty.

The political sustainability creates economic sustainability. Infrastructure providers are regulated, but they're also protected. Governments have strong incentives to ensure critical infrastructure remains stable and continues operating effectively. The regulatory oversight that once threatened Alibaba's existence now protects its market position from both domestic and foreign competitors.

The Market Mispricing

This transformation explains why Alibaba represents one of the most compelling investment opportunities in global technology today. Markets are still pricing the company based on its 2020 crisis rather than its 2025 reality.

The numbers support a measured revaluation rather than a dramatic repricing. China commerce revenue has returned to double-digit growth as platform monetization reaches steady state. Cloud revenue growth continues accelerating as AI adoption spreads across Chinese enterprises. Share buybacks and dividend payments resumed even during the heaviest infrastructure investment period, signaling management confidence in cash flow generation.

At 20 times forward earnings, the market has moved beyond crisis pricing and begun recognizing the transformation thesis. Current analyst expectations of 7-10% revenue growth and 20-30% EPS growth through 2028 suggest the market anticipates successful execution of the infrastructure strategy. The question for investors isn't whether Alibaba will recover—it's whether the company can exceed the elevated expectations now embedded in its valuation.

Yet Alibaba trades at 20 times forward earnings—still reasonable for a company undergoing infrastructure transformation, though the market has clearly recognized some of the transformation value. The current valuation reflects a market that's moved beyond crisis pricing but hasn't fully embraced the infrastructure thesis.

The risk analysis reveals the true opportunity. The old Alibaba was politically vulnerable because it concentrated market power in ways that threatened state authority. The new Alibaba is politically protected because it provides essential infrastructure that strengthens state capability.

Consider the three-year scenarios within this transformed context:

The Bull Case: Network Effects Achieved (US$340 target, 30% probability)

In this scenario, both infrastructure pillars exceed expectations and create the sustainable competitive advantages that justify the massive investment cycle. Revenue growth accelerates to 11-12% annually—well above current analyst expectations—as AI infrastructure and Quick Commerce achieve genuine network effects.

The mechanics are specific: Cloud intelligence revenue grows consistently above 20% annually, with AI-related products reaching 60%+ of external cloud business. Inference workloads—actual business usage rather than experimental training—dominate new demand, proving enterprises have become genuinely dependent on Alibaba's infrastructure.

Simultaneously, Quick Commerce proves its unit economics at scale. Delivery costs per order decline 10%+ year-over-year as density improves, while average order values expand across categories. Most crucially, Quick Commerce drives measurable cross-platform engagement, with users showing higher retention and spending across Taobao and Tmall.

Operating margins expand by 250-300 basis points as infrastructure investments achieve leverage. Combined with 3% annual share buybacks, EPS growth reaches 16-18% annually. At 18x earnings—reasonable for proven infrastructure with defensive characteristics—the stock hits US$340.

The Base Case: Steady Infrastructure Success (US$240 target, 50% probability)

More likely is solid execution without spectacular results. Revenue grows 8-9% annually as AI adoption spreads steadily and Quick Commerce expands methodically. Cloud intelligence grows 15-16% with AI products achieving meaningful scale. Quick Commerce reaches respectable user growth but unit economics remain challenging.

Operating margins expand by 100-150 basis points as some infrastructure investments pay off. EPS growth of 10-12% annually, supported by continued buybacks, justifies a 15x multiple and US$240 price target.

This represents successful transformation without dominant market position—Alibaba becomes solid infrastructure rather than unassailable platform.

The Bear Case: Infrastructure Without Returns (US$160 target, 20% probability)

The disappointment scenario is mediocre execution that fails to justify the investment cycle. Revenue growth slows to 4-6% annually as competitive pressure intensifies. Cloud growth stalls below 10% with limited AI adoption. Quick Commerce burns cash without achieving density economics. Operating margins remain flat as infrastructure costs exceed benefits.

EPS growth of just 3-5% annually leads to multiple compression. At 12x earnings—typical for mature, slow-growth Chinese tech—the stock declines to $160.

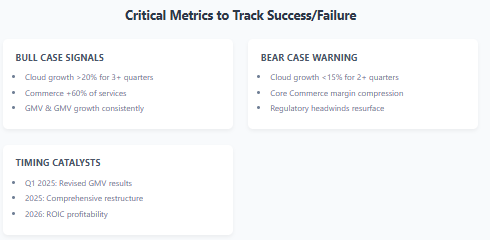

The Tracking Framework: Metrics That Determine Success

The power of this analysis lies in its measurability. Unlike many transformation stories that depend on subjective assessments, Alibaba's infrastructure thesis will generate specific, trackable results that determine which scenario unfolds.

Bull Case Validation Metrics (Next 12-24 months):

Cloud AI Infrastructure: External cloud growth consistently ≥12-15% year-over-year, with AI representing an increasing percentage of external cloud revenue each quarter. Inference workloads should exceed 60% of new demand, proving business dependency rather than experimental usage.

Commerce Monetization Discipline: China commerce revenue (CMR) equals or exceeds GMV growth in at least 3 of the next 4 quarters, proving the platform can grow revenue faster than transaction volume. Quanzhantui advertiser penetration and return-on-ad-spend must show consistent improvement.

Quick Commerce Unit Economics: Delivery cost per order declining ≥10% year-over-year while orders per rider per hour increase. Average order values expanding across product categories. Most critically, cohort breakeven achieved in Tier-1 and Tier-2 cities within 18 months.

International Profitability: Alibaba International Digital Commerce (AIDC) achieving its first profitable quarter, then maintaining sequential profitability.

Capital Allocation: Net share count reduction ≥3% annually while maintaining dividend payments, signaling management confidence in cash flow generation.

Bear Case Warning Signs:

The thesis breaks down if cloud growth falls below 10% for two consecutive quarters while AI mix remains flat. Additional red flags include CMR growing slower than GMV consistently, Quick Commerce unit costs staying flat or rising, and any policy headlines that revive regulatory tail risks.

These aren't subjective judgments—they're measurable outcomes that will determine whether Alibaba's infrastructure transformation creates the value that justifies current expectations and drives the stock toward US$340, or fails to deliver and sends it toward US$160.

The Historical Pattern

Alibaba's evolution follows a pattern that repeats throughout business history: companies that successfully navigate existential challenges often emerge stronger than before.

Carnegie's steel empire became more valuable after he accepted the limits of industrial expansion and focused on infrastructure rather than speculation. Rockefeller's wealth multiplied after Standard Oil's breakup forced him to diversify beyond pure oil monopoly. AT&T's regulated utility period generated steadier returns than its earlier competitive battles.

The pattern suggests a deeper truth about sustainable competitive advantage: the companies that survive regulatory pressure are those that evolve from trying to control markets to trying to enable markets. Platform dominance creates political resistance; infrastructure provision creates political protection.

This evolution is visible across the global technology industry today. Amazon's most valuable business isn't retail—it's AWS, the infrastructure service that enables other companies' digital transformation. Apple's highest-margin revenue comes from services that create switching costs rather than hardware that generates one-time sales. Microsoft's cloud transformation generated more value than its software licensing ever did.

The companies that recognize this pattern early and embrace infrastructure positioning voluntarily have better outcomes than those that resist until regulatory pressure forces change.

The Broader Implications

Alibaba's transformation provides a template for Chinese technology companies, the playbook is now clear: infrastructure positioning beats platform competition in a regulatory environment that prioritizes stability over disruption. ByteDance, Tencent, and other Chinese platforms face similar pressures and will likely follow similar evolutionary paths.

For investors, the lesson is that traditional platform valuation methods may not apply to companies undergoing infrastructure transformations. The metrics that matter—dependency, switching costs, integration effects, political sustainability—are different from the user growth and engagement metrics that drive pure platform valuations.

The strategic question facing every major platform is a variation of what Alibaba confronted: When success becomes politically unsustainable, what infrastructure do you control that others depend on?

Full Circle: The Speech That Saved Everything

Jack Ma's speech at the Bund Summit was supposed to be his crowning achievement—the final validation of a vision that had transformed Chinese commerce and made him one of the world's most successful entrepreneurs.

Instead, it became the catalyst for the most important strategic pivot in modern business history.

The regulatory crisis that followed wasn't just punishment for political miscalculation—it was the pressure necessary to force evolution beyond platform dominance toward infrastructure dependency. The company that emerged from that crisis isn't the same as what came before, but it may be more valuable.

Andrew Carnegie understood this dynamic intuitively: sometimes the most successful strategic moves are forced on you by circumstances beyond your control. The regulatory constraints that ended his steel empire's expansion created the pressure necessary to transform from robber baron to philanthropist, securing a legacy that outlasted his corporate achievements.

Jack Ma's journey follows a similar arc. The entrepreneur who once challenged state authority now serves state objectives. The platform that once concentrated market power now distributes technological capability. The company that was nearly broken by regulatory pressure has been strengthened by regulatory alignment.

The old Alibaba was built on the premise that platforms could transcend traditional limitations—regulatory, competitive, or political. The new Alibaba is built on the premise that the most sustainable success comes from making those limitations into advantages.

Sometimes the best strategic moves are forced on you by the speeches you shouldn't have given, the regulations you couldn't avoid, and the crises that reveal opportunities you were too successful to see. Jack Ma learned Carnegie's lesson the hard way.

Disclaimer:

The content does not constitute any kind of investment or financial advice. Kindly reach out to your advisor for any investment-related advice. Please refer to the tab “Legal | Disclaimer” to read the complete disclaimer.