Jiangxi Copper: The Accidental Gold Company

Jiangxi Copper's processing fees collapsed to zero. Its gold and chemicals business is now the entire investment case.

TL;DR

The fee that defined copper smelting no longer exists. Benchmark TC/RC collapsed from $80/tonne (2024) to $0. Jiangxi Copper’s core processing business, the reason it was built, now generates approximately zero profit.

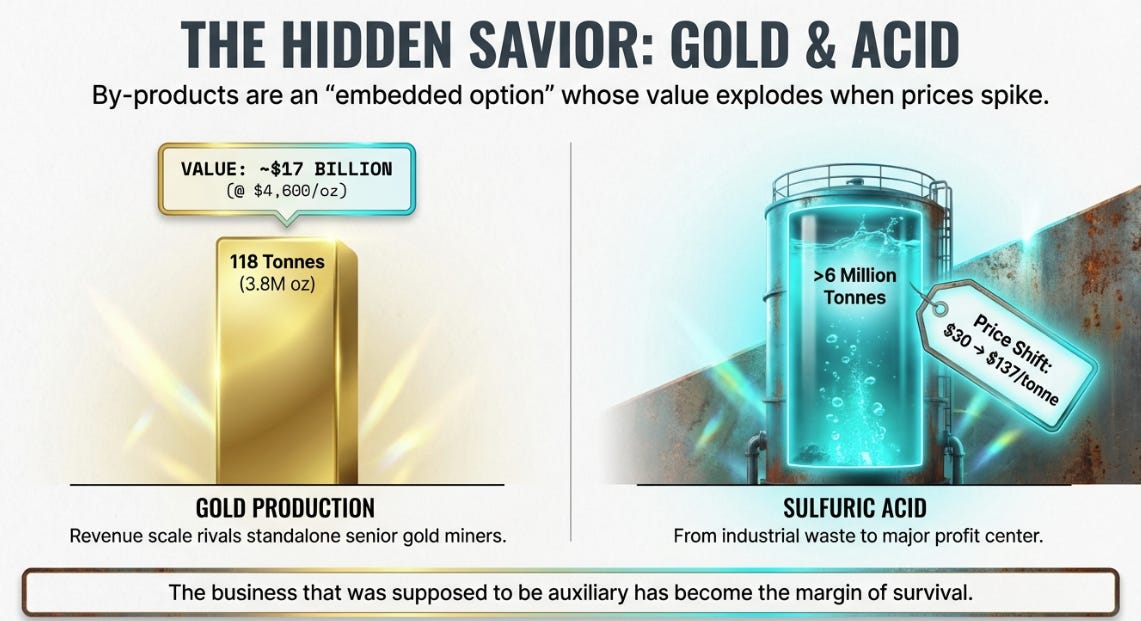

By-products have become the business. Gold at $4,600/oz and sulfuric acid at $137/tonne have transformed what were once supplementary credits into the dominant profit driver. Jiangxi produces 118 tonnes of gold annually, output rivaling mid-tier gold miners.

The market is valuing the wrong company. Consensus still prices Jiangxi as a “troubled copper smelter awaiting TC/RC recovery.” The current profit mix suggests it’s closer to an integrated gold-chemicals producer. That classification gap is the opportunity—or the trap, if by-products normalize.

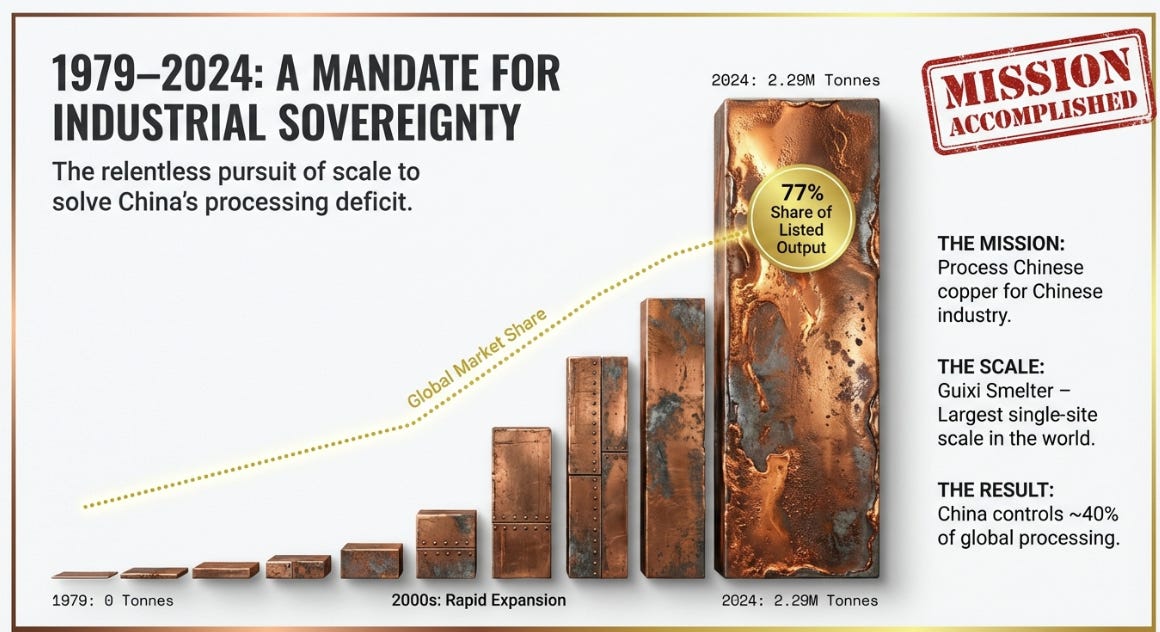

In 1979, the same year Deng Xiaoping launched the reforms that would transform China into the world’s factory, a state-owned copper project was established in Jiangxi Province with a straightforward mission: process Chinese copper for Chinese industry.

The logic was compelling. China had copper ore,the massive Dexing deposit held one of Asia’s largest reserves, but lacked capacity to turn that ore into usable metal. Every tonne of copper wire in a Chinese factory was either imported as refined metal or shipped abroad as concentrate to be processed by Japanese or European smelters. Building domestic smelting capacity wasn’t just economics. It was industrial sovereignty.

Over the following decades, that state project evolved into Jiangxi Copper Company Limited, formally established in 1997 and listed on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange. The company built the Guixi smelter, described in its own filings as having the largest single-site smelting scale in the world. It expanded relentlessly: 500,000 tonnes of annual capacity, then one million, then two million. By 2024, Jiangxi Copper produced 2.29 million tonnes of refined copper cathode, capturing 77% of output among China’s listed copper smelters. China itself went from negligible smelting capacity to controlling roughly 40% of global copper processing.

Mission accomplished.

But here’s the thing about winning: sometimes the game changes while you’re celebrating.

The Fee That Defined Everything

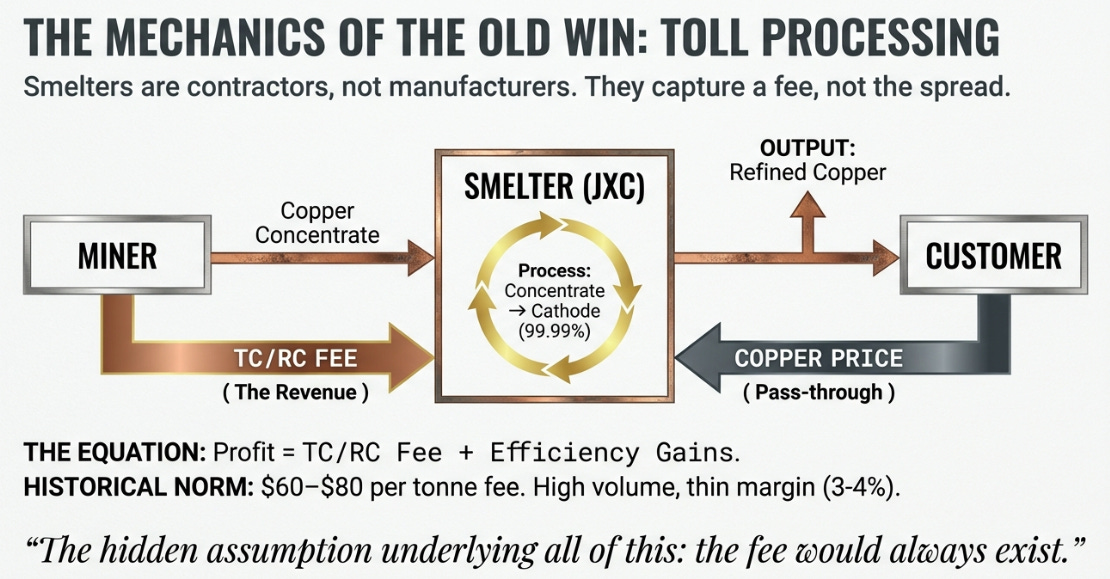

To understand what happened to Jiangxi Copper, you need to understand how copper smelting actually makes money,or at least, how it used to.

Copper smelters don’t really “make” copper. They convert copper concentrate (the output of mines, typically 25-30% copper content) into copper cathode (99.99% pure copper registered on the London Metal Exchange). They’re contractors, not manufacturers. The business model is toll processing: miners pay smelters a fee,called treatment charges and refining charges, or TC/RC,to perform this conversion.

For decades, benchmark TC/RC hovered around $60-80 per tonne of concentrate. This fee was the smelter’s margin. Buy concentrate at a discount to LME copper price, sell refined cathode at LME price, pocket the spread. The economics were thin,gross margins of 3-4% were normal,but volumes were enormous, and the business was predictable. If you could process more metal more efficiently than competitors, you won.

Jiangxi Copper was built to win this game. Scale. Throughput. Operational discipline. The company’s identity, its source of pride, was being the biggest and most efficient processor in the world.

The hidden assumption underlying all of this: the fee would always exist.

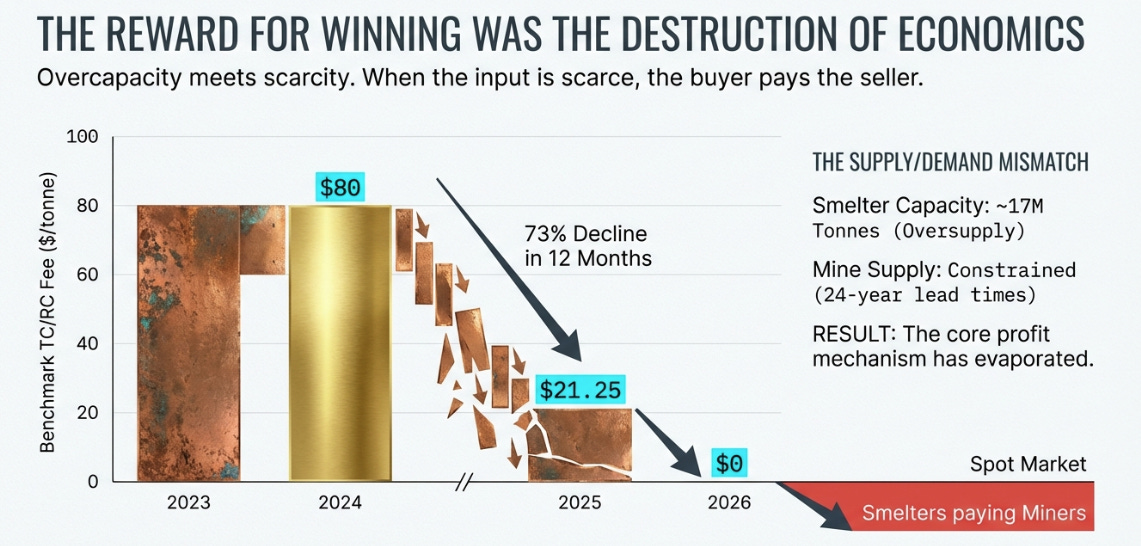

In 2024, benchmark TC/RC was $80 per tonne. In 2025, it collapsed to $21.25,a 73% decline in a single year. For 2026, industry sources report the benchmark settled at zero. Spot rates have gone negative. Smelters now pay miners for the privilege of processing their concentrate,a phenomenon the company’s own interim commentary describes as TC/RC quotes falling into “significantly negative territory.”

The fee that defined Jiangxi Copper’s business model for decades has ceased to exist.

The mechanism is straightforward, even if the implications are profound. China built 16-17 million tonnes of annual smelting capacity. Global copper mine supply, constrained by geology and permitting timelines averaging 24 years from discovery to production, didn’t keep pace. Too many smelters started chasing too little concentrate. When the input is scarce, the buyer stops being a buyer.

China won the smelting industry by building more capacity than anyone else. The reward for winning was the destruction of the economics that made winning worthwhile.

The Three Engines

If Jiangxi Copper’s core business no longer generates meaningful profits, why has the stock roughly tripled over the past 18 months? Why have multiple brokers issued aggressive upgrades?

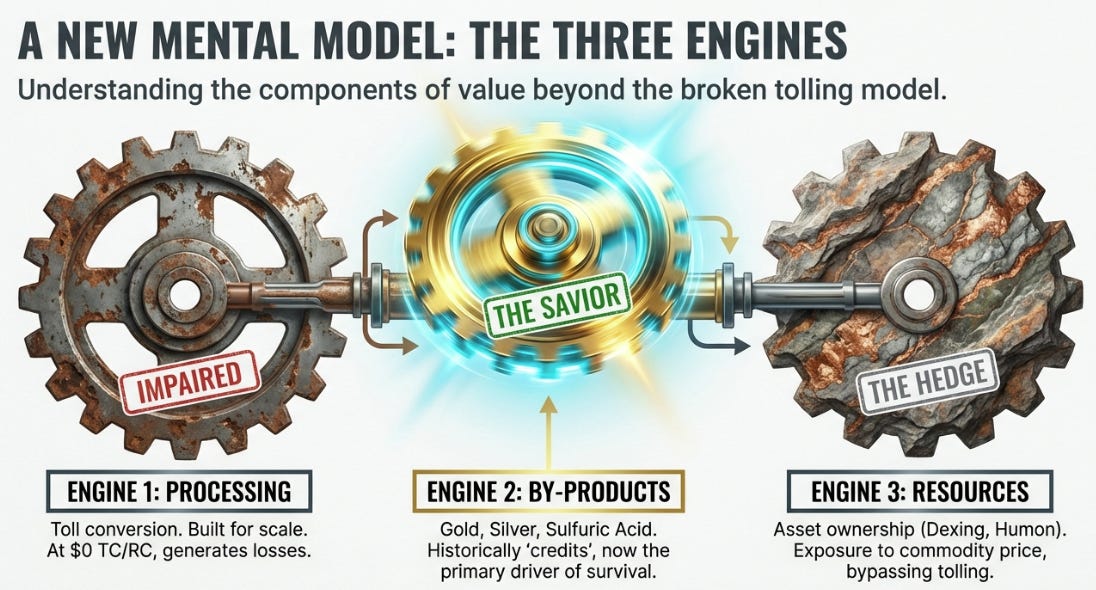

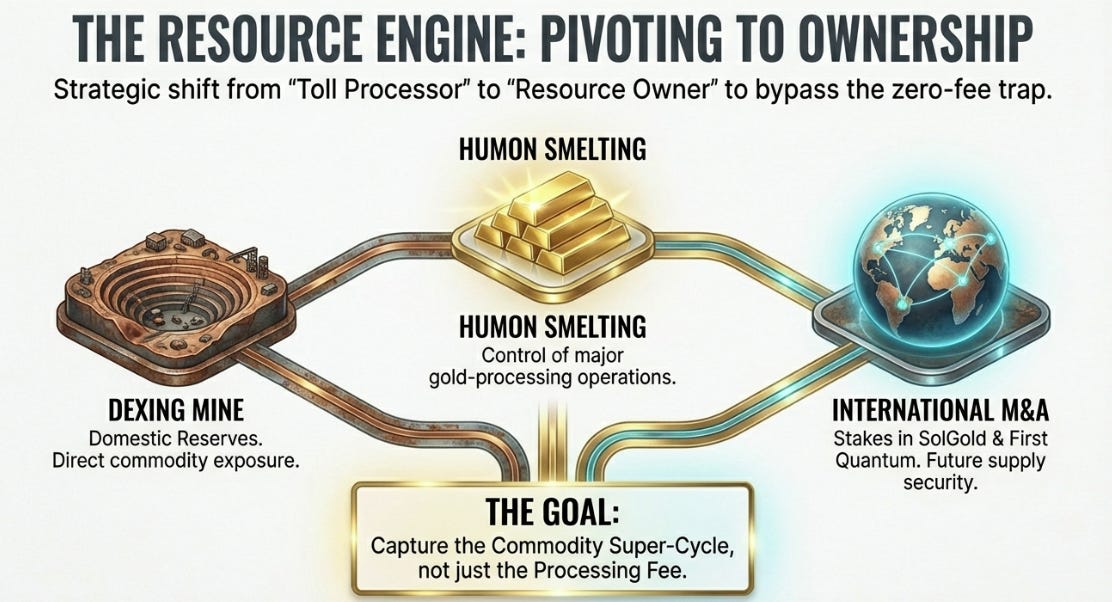

The answer requires a different mental model for understanding the company. Forget “copper smelter.” Think instead about three distinct engines:

The Processing Engine: Toll conversion of concentrate to cathode. This is what Jiangxi Copper was built for. At zero TC/RC, this engine is impaired,generating somewhere between minimal contribution and outright losses.

The By-Product Engine: When you process copper concentrate, you also extract gold, silver, and produce sulfuric acid. These were always treated as supplementary,credits that smoothed earnings volatility. The company’s 2024 production data tells a different story: 118 tonnes of gold, over 6 million tonnes of sulfuric acid. These are not rounding errors.

The Resource Engine: Jiangxi Copper owns the Dexing mine and controls Humon Smelting, a major gold-processing operation. It has been acquiring stakes in mining assets internationally. This provides exposure to commodity prices without TC/RC drag.

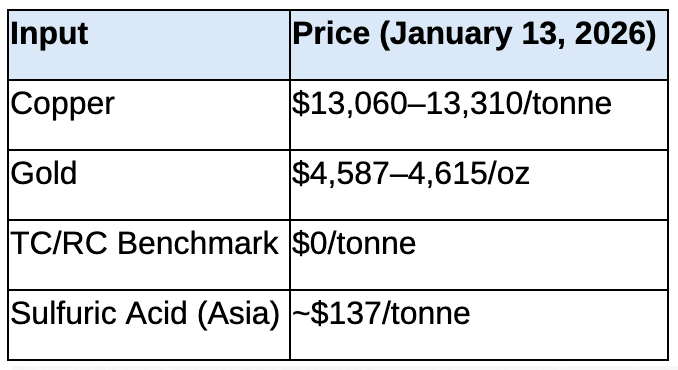

Now look at today’s scoreboard:

Copper is near record highs. But that doesn’t help the Processing Engine when the fee is zero,revenue goes up, but so do input costs, and the spread remains nonexistent.

Gold, however, is at all-time highs. At current prices, Jiangxi Copper’s gold output of roughly 118 tonnes translates to approximately 3.8 million ounces,worth over $17 billion, or north of RMB 120 billion at current exchange rates. Even accounting for payables embedded in concentrate purchasing terms (smelters typically don’t capture 100% of contained precious metal value), the contribution is enormous. By-products function as an embedded option whose value explodes when prices spike.

Sulfuric acid, historically an afterthought priced around $30-40 per tonne, now trades above $130 in Asia. The company produces over 6 million tonnes annually.

The Processing Engine is impaired. But the By-Product Engine is running at maximum output. And the Resource Engine,enhanced by the Humon gold operations and international mining stakes,provides structural exposure that isn’t hostage to TC/RC dynamics.

This is the insight the market hasn’t fully processed: Jiangxi Copper increasingly resembles a precious metals and chemicals producer that happens to smelt copper, rather than a copper smelter that happens to produce gold. The business that was supposed to be auxiliary has become the margin of survival,and potentially, the source of real profitability.

The Variant Perception

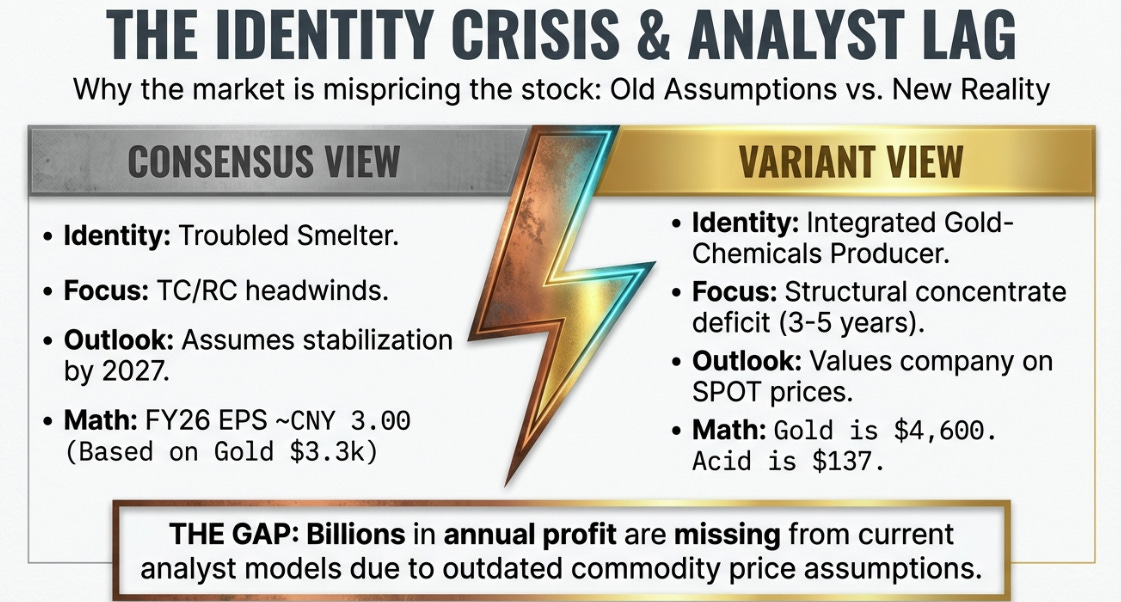

The consensus view on Jiangxi Copper goes something like this: it’s a copper play with defensive characteristics. State backing provides downside protection. Scale advantages ensure survival. By-products offer temporary margin support while the TC/RC environment normalizes.

This view is incomplete in important ways.

Start with TC/RC recovery. The consensus expects stabilization by 2027. But Chinese smelting capacity continues growing while mine supply remains constrained. The concentrate deficit isn’t temporary,it’s structural. TC/RCs may remain impaired for three to five years.

More importantly, consensus estimates haven’t caught up to by-product prices. Analyst models for FY2026 cluster around CNY 3.00 earnings per share. Those estimates were built when gold was $3,300 and sulfuric acid was $60. Gold is now $4,600. Sulfuric acid is $137. At current prices, by-product contribution alone adds billions to annual profits versus what the models assume.

The deepest misunderstanding is about identity. The market categorizes Jiangxi Copper as a “troubled smelter facing TC/RC headwinds.” Given the current profit mix, it might better be categorized as an “integrated copper-gold-chemicals producer”,a different business with different risk characteristics.

Management seems to understand this. The aggressive M&A,SolGold, First Quantum,isn’t random diversification. It’s acknowledgment that the Processing Engine is structurally challenged and the company needs to shift toward resource ownership.

The Scenarios

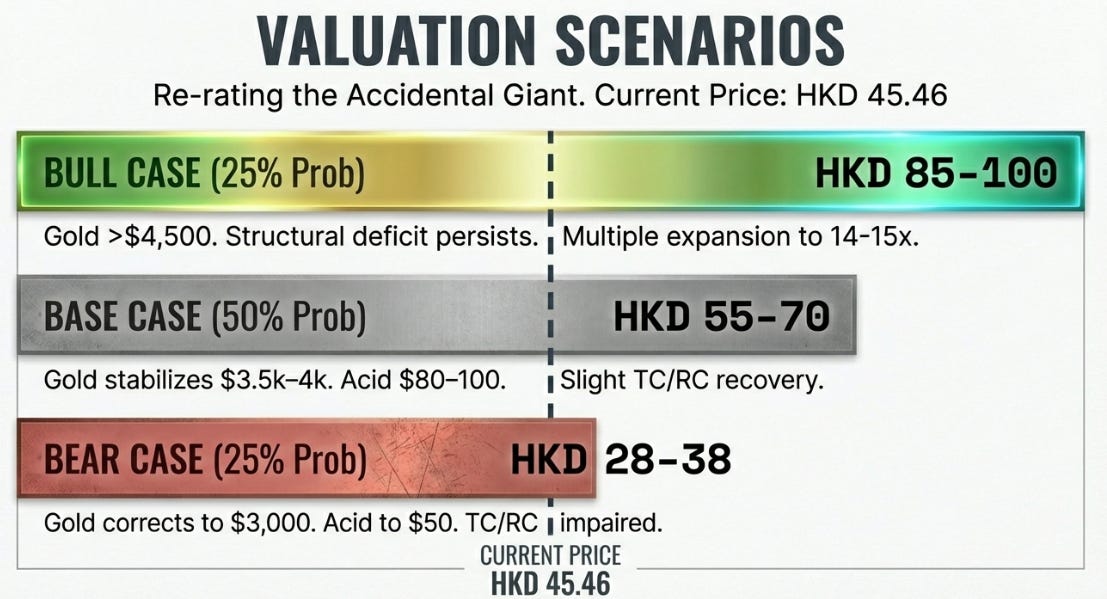

Three-year price targets require explicit assumptions. Starting from HKD 45.46:

Bear Case: HKD 28-38 (Probability: 25%)

By-products normalize. Gold corrects to $3,000 as macro conditions shift. Sulfuric acid reverts to $50-60. TC/RCs remain impaired. Revenue declines modestly. Net margins compress to 1.0-1.3%. FY2028 EPS: CNY 2.20-2.80. Multiple: 10-11x.

Base Case: HKD 55-70 (Probability: 50%)

By-products moderate but stay elevated. Gold stabilizes around $3,500-4,000. Sulfuric acid settles at $80-100. TC/RCs recover slightly. Revenue grows 3-5% annually. Net margins: 1.5-1.8%. FY2028 EPS: CNY 3.50-4.20. Multiple: 12-13x.

Bull Case: HKD 85-100 (Probability: 25%)

Gold’s structural bid proves durable above $4,500. Copper super-cycle materializes. Resource Engine gains value through M&A execution. Revenue grows 7-10% annually. Net margins expand to 2.0-2.5%. FY2028 EPS: CNY 5.00-6.00. Multiple: 14-15x.

At HKD 45, the stock is fairly valued,not obviously cheap. At HKD 38-42, the risk-reward improves materially. At HKD 28-32, you’d be paying for by-product normalization while retaining all the upside optionality.

What to Watch

The thesis lives or dies on by-products.

Gold price: Above $4,000, the embedded option pays off handsomely. Below $3,000, the earnings base erodes.

Sulfuric acid: Above $100/tonne, meaningful contribution. Below $60, rounding error.

Quarterly gross margin: Above 3.2% suggests by-products are carrying the business. Below 2.8% suggests the offset is fading.

TC/RC direction: Not because recovery is imminent, but because further deterioration would signal even worse processing economics.

The Arc Completed

Return to 1979. Deng’s reformers established a copper project in Jiangxi to solve a specific problem: China needed to process its own copper. Over the following decades, that project became a listed company that built the largest smelting operation on Earth.

The twist is that the business they built no longer drives profits. The Processing Engine that defined Jiangxi Copper’s identity now contributes minimally when fees collapse to zero. When the fee disappears, scale stops being sufficient. Efficiency stops being sufficient.

What matters instead is something the founders never planned for: by-products. Gold extracted during copper processing. Sulfuric acid generated as chemical output. These supplementary businesses, enhanced by controlled assets like Humon Smelting, have become the difference between losses and profits.

China set out to build a copper smelter. It ended up with something that increasingly resembles a gold-and-chemicals company.

The market hasn’t fully processed this. It still values Jiangxi Copper through the lens of TC/RC recovery and processing margins,the old game. The opportunity lies in recognizing the new reality: a company mentally filed as “troubled industrial” that’s generating earnings like a precious metals producer.

Whether that opportunity is attractive at HKD 45 depends on a question that has nothing to do with copper, smelting, or industrial policy: will gold stay above $4,000?

If yes, the stock is cheap. If no, it isn’t.

Sometimes the most valuable thing a company produces is something it never planned to make.

Disclaimer:

The content does not constitute any kind of investment or financial advice. Kindly reach out to your advisor for any investment-related advice. Please refer to the tab “Legal | Disclaimer” to read the complete disclaimer.