Micron - The Librarians' Dilemma: How AI Broke the Memory Market

AI shifted the bottleneck from compute to data access—and HBM lock-in, packaging constraints, and geopolitics are breaking the 40-year memory cycle, with Micron emerging as a structural winner.

TL;DR:

AI changed the constraint. Inference, video, and autonomy are memory-bound, not compute-bound—making bandwidth, latency, and proximity (HBM) more valuable than raw FLOPs.

Supply can’t respond like it used to. CoWoS packaging limits, 18–42 month qualification lock-ins, 3–5 year fab timelines, and HBM’s 3:1 cannibalization of DDR break the old boom-bust playbook.

Memory is no longer fungible. Custom HBM, geopolitical fragmentation, and co-development give suppliers pricing power—pushing Micron into a margin regime that once seemed impossible.

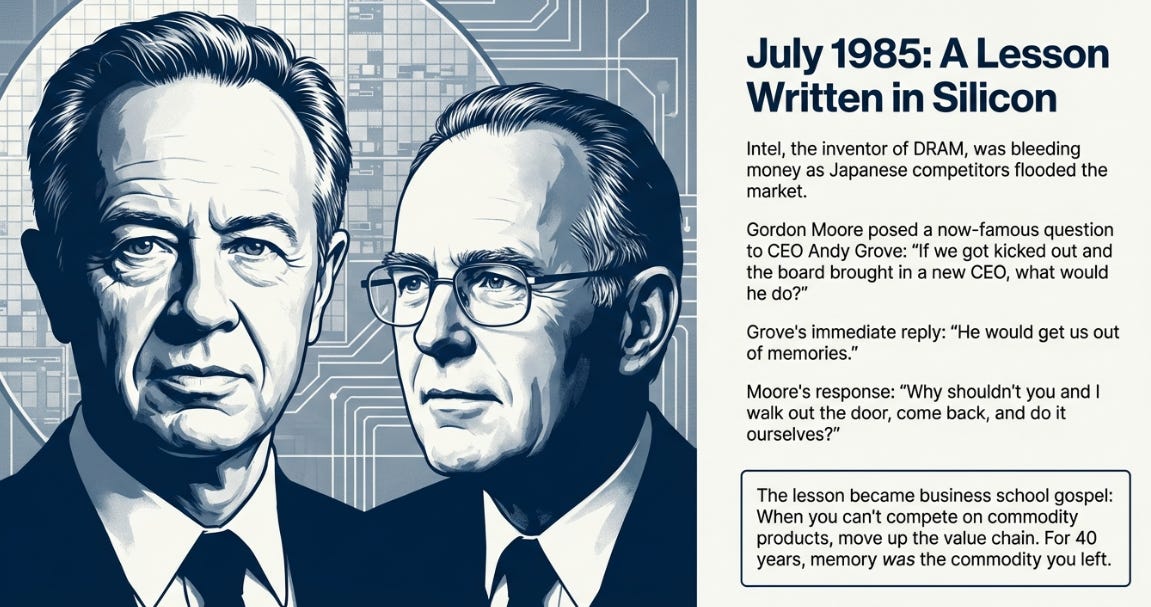

July 1985: The Beginning of a Pattern

Andy Grove didn’t want to exit DRAM. Intel had invented the technology in 1971 and built its early fortune on memory chips. But by 1985, Japanese manufacturers—Hitachi, NEC, Toshiba—were flooding the market with cheaper, higher-quality products. Intel’s DRAM division was bleeding money.

Gordon Moore, Intel’s chairman, asked Grove a simple question: “If we got kicked out and the board brought in a new CEO, what would he do?”

Grove answered immediately: “He would get us out of memories.”

Moore looked at him and said: “Why shouldn’t you and I walk out the door, come back, and do it ourselves?”

They did. Intel exited DRAM production and bet everything on microprocessors. The decision became business school gospel: when you can’t compete on commodity products, move up the value chain to where differentiation matters.

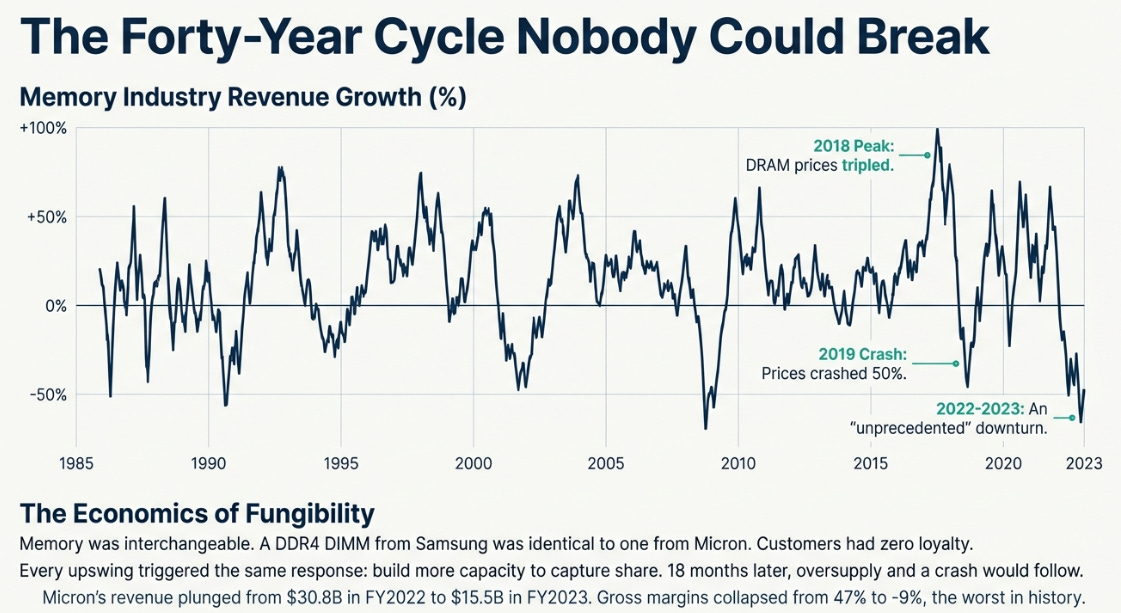

For the next forty years, that lesson shaped the memory industry. Memory was the thing you left to focus on higher-margin businesses. It was fungible, cyclical, brutal. No matter how much the industry consolidated—ten players to five to three—the boom-bust pattern held. Prices would spike, everyone would build fabs, and 18 months later there’d be oversupply and another crash.

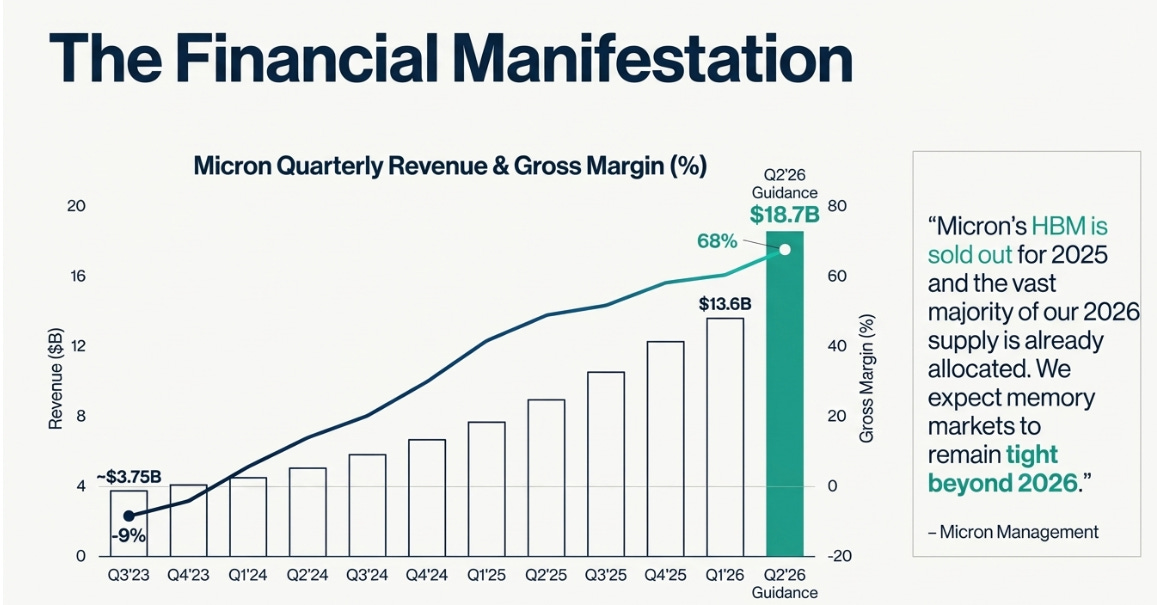

The pattern repeated in 2018: DRAM prices tripled, manufacturers announced expansions, and by 2019 prices crashed 50%. In 2023, it got worse—Micron reported negative 9% gross margins, the worst in history. All three survivors (Samsung, SK Hynix, Micron) came within quarters of financial crisis. Memory was commodity. Always had been, always would be.

Except something strange started happening in 2024. The shortage that followed didn’t behave like previous cycles. Prices kept rising, but supply didn’t flood the market. Qualification timelines stretched. Lead times extended. And by late 2025, Micron was guiding to 68% gross margins—a number that should have been impossible.

I’ve been covering this industry long enough to know what peak margins mean: the crash is coming. But the more I dug into the numbers, the less the old pattern fit. The constraint had moved. And when constraints move, power moves with them.

The Forty-Year Cycle Nobody Could Break

Let me be clear about what made memory a commodity. It wasn’t just price competition—it was interchangeability. A DDR4 DIMM from Samsung worked identically to one from Micron or SK Hynix. They followed the same JEDEC standards, had the same pinouts, delivered the same performance. Switching suppliers took days, maybe weeks for qualification testing.

This fungibility created vicious economics. When prices rose, customers had zero loyalty. They’d switch to whoever offered the lowest price. Every manufacturer knew this, which meant every upswing triggered the same response: build more capacity to capture share. The cycle turned in eighteen months, just like it always did.

And then AI happened.

When Compute Stopped Being the Bottleneck

Here’s what nobody saw coming: AI didn’t just increase demand for memory. It changed what kind of demand in ways that made the old supply response impossible.

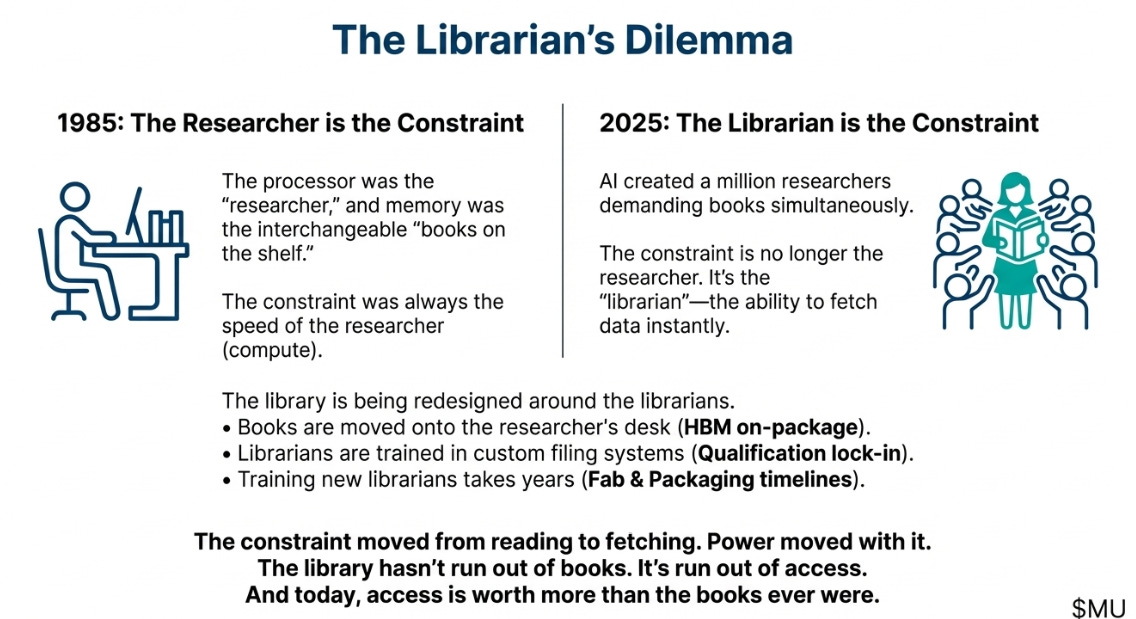

Think about a traditional workload. You’re running a database or a web server. The processor does work (compute), pulls data from memory when needed, does more work. The constraint is usually the processor—how fast can it compute? Memory just needs to be big enough and fast enough to keep the processor fed.

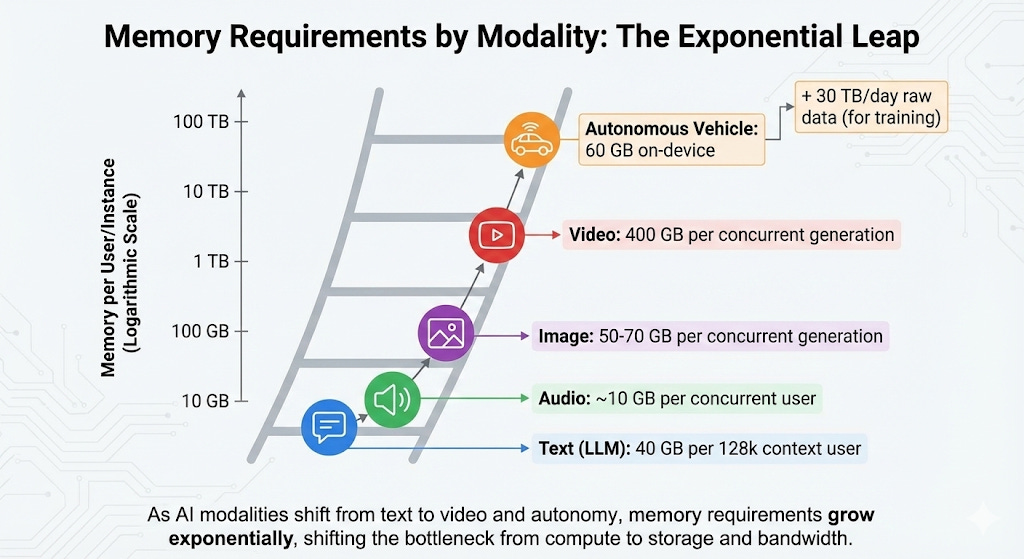

AI inference is different. OpenAI’s latest model doesn’t just pull its weights from memory and compute an answer. It stores the entire conversation history—every token you’ve sent, every token it’s generated—in what’s called a key-value cache. That 128,000-token context window everyone was excited about? It requires 40GB of memory per user. Not for the model weights, just for the conversation history.

A million concurrent users means 40,000GB of memory, just for context. And their next model is rumored to support a million tokens. That’s not just impressive—it’s 40TB of memory for a million concurrent users, just to remember what was said.

But wait, it gets worse. Video generation is even more memory-intensive. A video model processes a four-dimensional tensor: time × height × width × color channels. The intermediate activations—the temporary data needed at each diffusion step—can consume 25× more memory than an equivalent image model. Runway’s Gen-3 or OpenAI’s Sora generating a one-minute video at 1080p might require 400GB of working memory per concurrent generation. Not storage—working memory.

Or consider autonomous vehicles. Tesla’s Hardware 4.0 packs 60GB of DRAM on-device just to process sensor data in real-time. A single advanced self-driving car generates roughly 30TB of raw sensor data per day from cameras, radar, and lidar. The vehicle uploads only a few GB of “interesting” events, but a million-vehicle fleet is generating petabytes monthly for training. Each training cluster needs hundreds of gigabytes of high-bandwidth memory per GPU to process this flood.

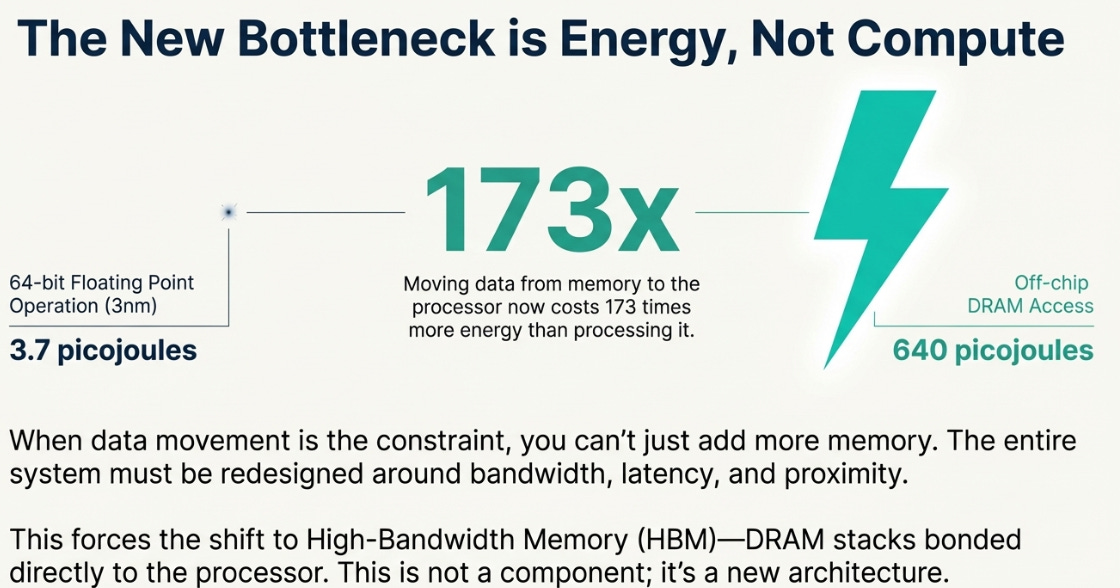

This isn’t just “more AI means more memory.” It’s a fundamental architectural shift. In traditional computing, moving data from memory to the processor cost roughly the same energy as doing a few dozen calculations. By 2025, with processors manufactured at 3nm and DRAM scaling much slower, a single memory access can cost 173× more energy than a single floating-point operation.

When moving data costs 173× more than processing it, you can’t just add more memory. You need fundamentally different memory—faster, closer, more power-efficient. You need to redesign the entire system around the constraint.

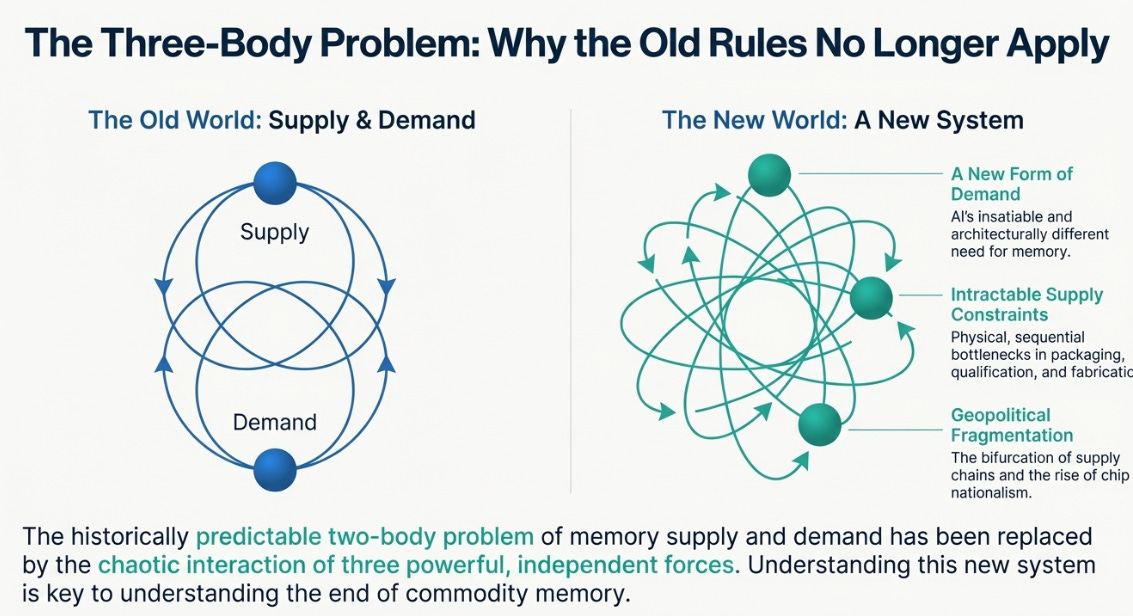

This explosion in demand would normally trigger a massive supply response. But this time, it can’t. The supply side is now constrained by its own three-body problem: a crisis in packaging capacity, a lock-in from qualification timelines, and a multi-year lag in fab construction.

The Timeline That Doesn’t Fit

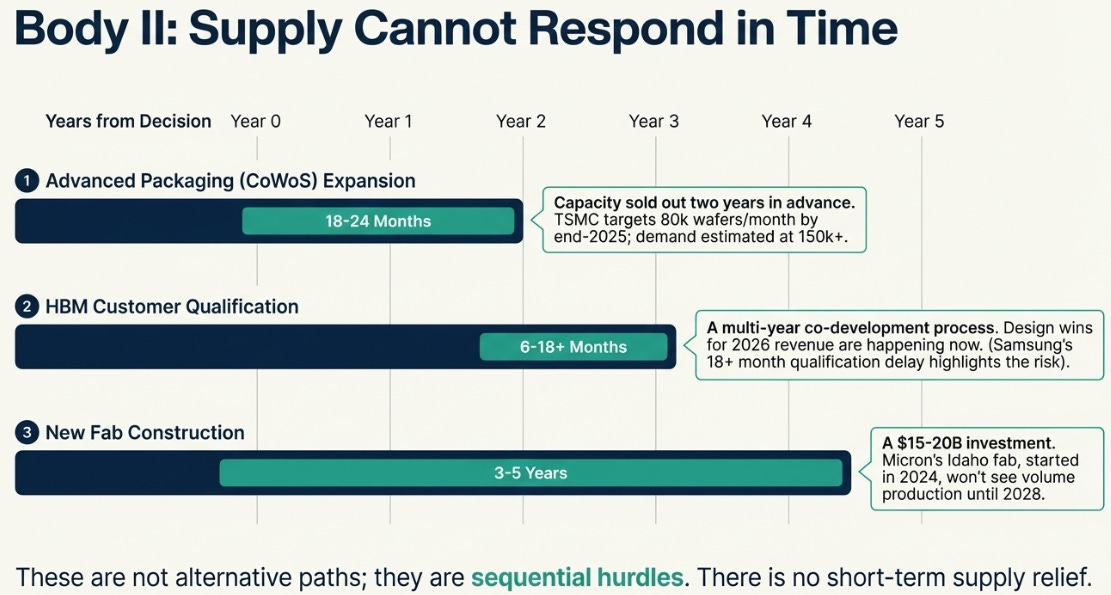

I kept trying to map out the supply response timeline and hitting the same wall. The numbers didn’t line up. Packaging capacity said 18-24 months to expand. Qualification timelines said 24-42 months. New fab construction said 3-5 years.

At first I thought these were alternatives—different paths to solving the shortage. Then I realized they weren’t alternatives at all. They were sequential. And that’s when it hit me: this wasn’t one constraint, but three independent forces operating on different clocks.

High-bandwidth memory (HBM)—the type AI accelerators require—isn’t a stick of RAM you slot into a motherboard. It’s a 3D stack of DRAM chips bonded directly to the GPU using thousands of microscopic connections (through-silicon vias) on a silicon interposer. This integration happens at specialized packaging facilities, primarily TSMC’s CoWoS (Chip-on-Wafer-on-Substrate) lines.

In 2022, TSMC could process 12,000 CoWoS wafers monthly. By late 2024, they’d expanded to 45,000. By end of 2025, the target is 80,000. But AI demand requires an estimated 150,000+ monthly. The packaging lines are sold out more than two years in advance. Expanding CoWoS capacity takes 18-24 months: clean room construction, equipment installation, yield ramp. Intel is offering its EMIB packaging as an alternative, but qualifying a new packaging process takes another 12-18 months minimum. You can’t just flip a switch.

But that’s only the first constraint. Standard DRAM qualification—ensuring a chip works in a system—takes 3-6 months. HBM qualification takes 6-9 months minimum, sometimes 18-42 months when custom features are involved. NVIDIA’s Blackwell GPU, shipping in 2024-2025, uses HBM that was qualified in 2023. The Rubin GPU, expected in 2026, is using HBM being qualified right now in 2025. Revenue that will show up in 2027 is being locked in during 2025’s qualification cycles. This isn’t a spot market—it’s a multi-year co-development process where design wins happen 24-36 months before revenue.

And finally, there’s fab capacity itself. Building a leading-edge DRAM fab requires $15-20 billion and takes 3-5 years from investment decision to volume output. Micron’s Idaho fab, announced in 2024, will produce its first wafer in mid-2027 and reach volume production in 2028. SK Hynix is investing $500 billion over ten years, with the first new fab targeting 2027. The industry learned caution after the 2023 near-death experience. Nobody wants to trigger another crash. But this caution means new supply won’t arrive until 2027-2028 at the earliest.

Now here’s where it gets genuinely weird. These three constraints don’t just add up—they interact. And there’s a fourth element that makes it worse: HBM production actually reduces standard DRAM supply.

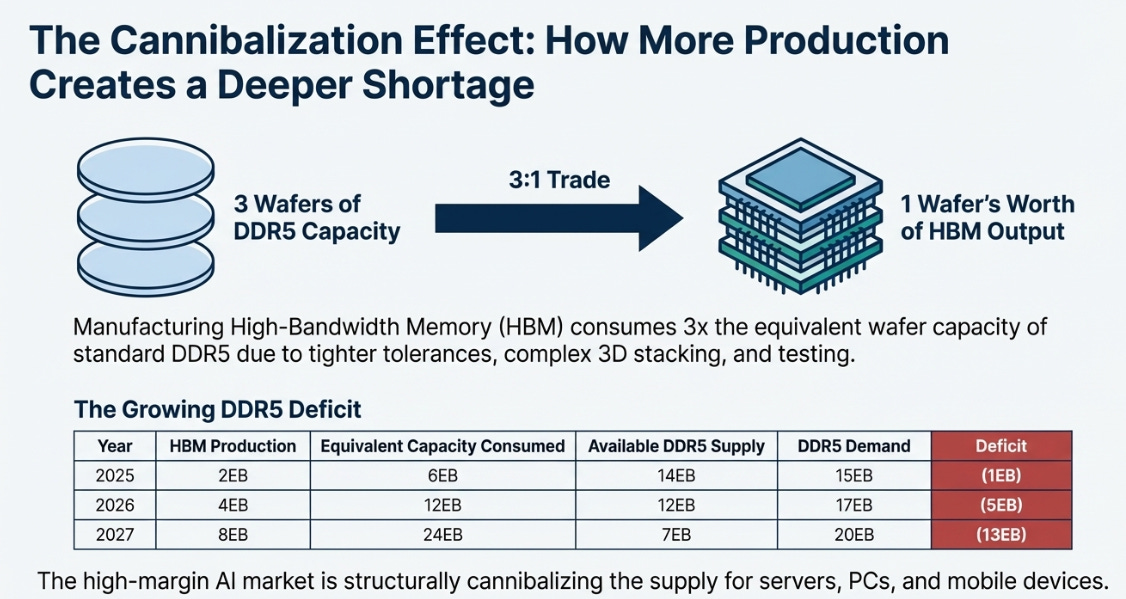

Manufacturing HBM requires tighter tolerances, more testing, and complex stacking—effectively consuming three wafers’ worth of capacity to produce one wafer of HBM output. It’s a 3:1 trade ratio. As HBM production doubles (growing 40%+ annually to meet AI demand), standard DDR5 supply tightens even as total wafer capacity grows.

The math is genuinely counterintuitive:

More production creates a worse shortage. The high-margin AI market is cannibalizing supply for everything else.

Of course, there’s a third force that’s reshaping all of this, and it’s not technical—it’s political.

The Geopolitical Wildcard

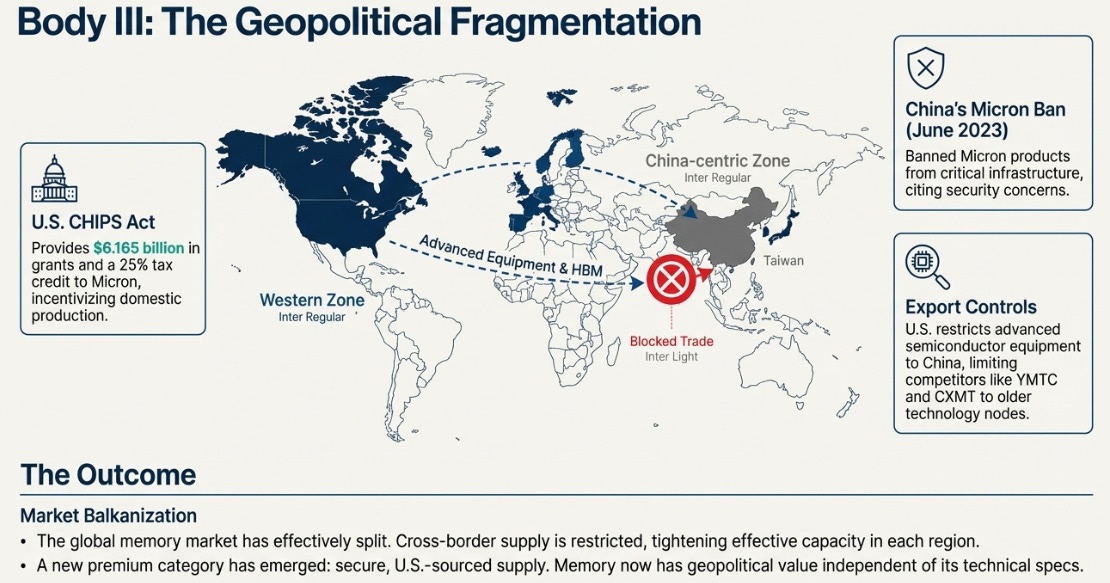

In June 2023, China’s Cyberspace Administration banned Micron products from critical infrastructure, citing security concerns. The U.S. had already restricted exports of advanced semiconductor manufacturing equipment to China. By 2024, the bifurcation was complete: Chinese manufacturers (YMTC, CXMT) could produce DDR4-class DRAM and older NAND but remained years behind on cutting-edge technology. Western markets had three suppliers effectively locked in.

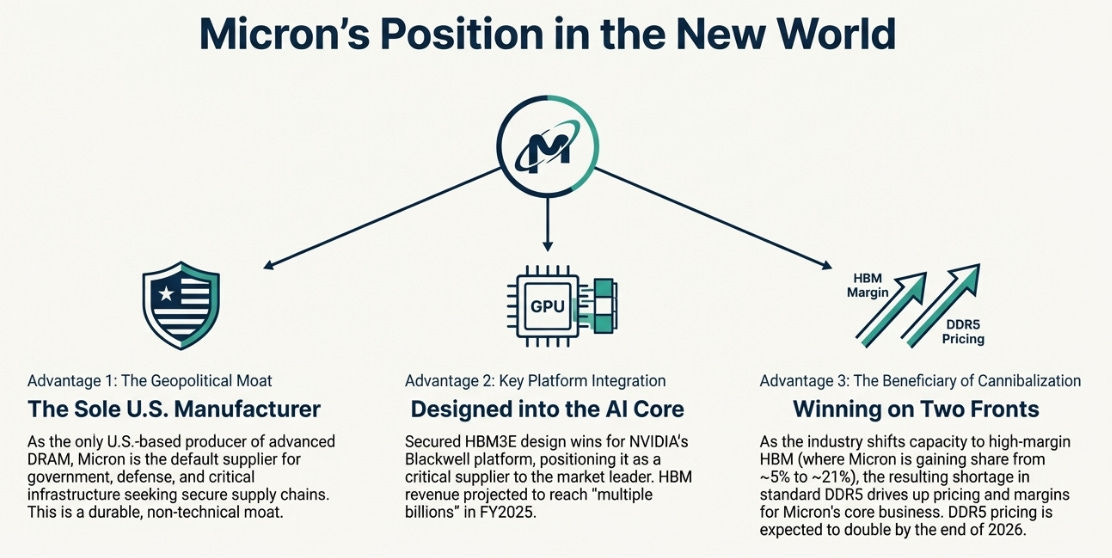

The U.S. CHIPS Act provides $52.7 billion for domestic semiconductor manufacturing. Micron received $6.165 billion in grants plus a 25% investment tax credit. This isn’t just about dollars—it’s about supply chain resilience.

For certain customers—government contracts, defense applications, critical infrastructure—”Micron” increasingly means “U.S.-sourced supply.” It’s a premium category that didn’t exist five years ago. Memory has geopolitical value independent of technical specifications.

The result is market Balkanization. Wafers produced in China serve Chinese customers; wafers produced in the West serve Western customers. Cross-border supply is restricted by export controls and national security concerns. The global market has effectively split, which structurally tightens supply in each region.

So we have three forces: exploding demand that can’t be met with traditional memory, supply constraints operating on 18-month to 5-year timelines, and geopolitical fragmentation reducing effective global capacity. They’re all happening simultaneously, and they interact in non-linear ways.

It’s a three-body problem. And three-body problems don’t have clean solutions.

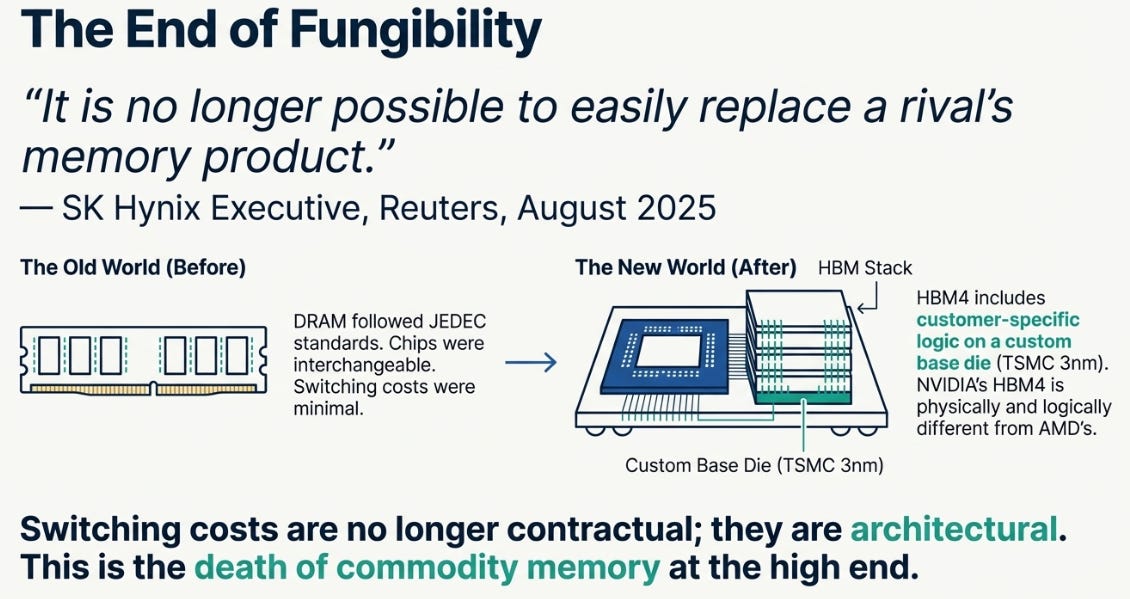

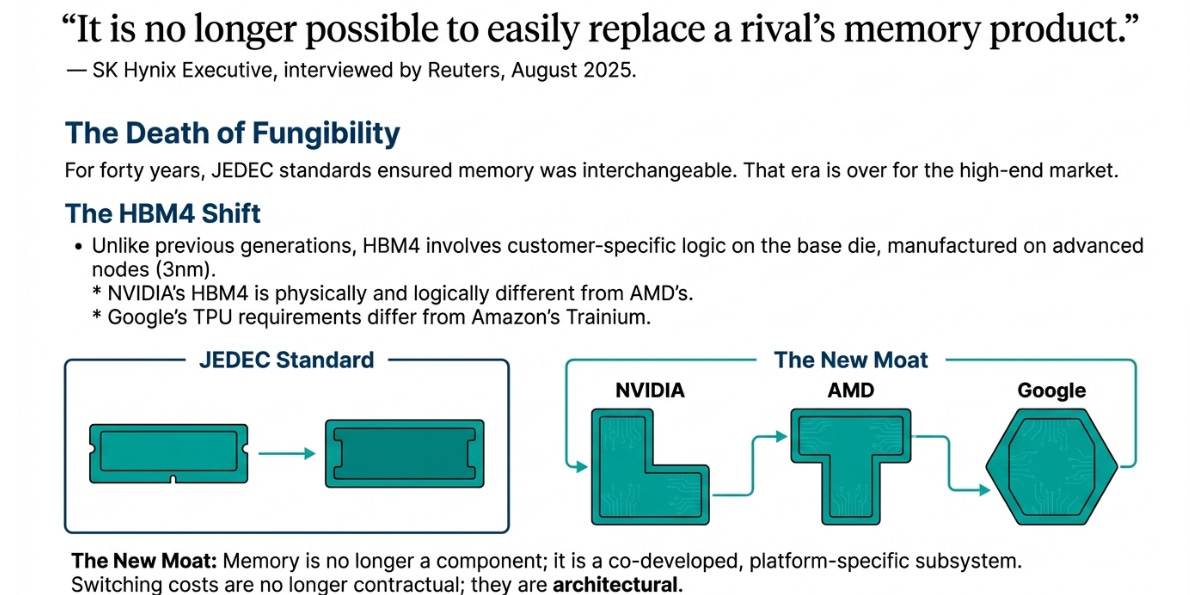

The End of Fungibility

In August 2025, Reuters interviewed SK Hynix executives about the next generation of HBM. One sentence jumped out:

“It is no longer possible to easily replace a rival’s memory product.”

Think about that sentence. For forty years, memory was definitionally replaceable. That was the whole point—JEDEC standards existed so you could swap Samsung for Micron for SK Hynix with minimal friction. This isn’t just a technical observation. It’s a business model change. What SK Hynix is really saying is: we have pricing power now, because you can’t switch to Samsung without redesigning your chip.

This was about HBM4, shipping in 2026. Unlike HBM3, which follows standardized JEDEC specs, HBM4 includes customer-specific logic on the base die. The base die—the bottom layer of the HBM stack—is being manufactured on advanced logic nodes (3nm) at foundries like TSMC, with custom circuits designed for specific customers.

NVIDIA’s HBM4 is physically and logically different from AMD’s. Google’s TPU requirements differ from Amazon’s Trainium. Each is custom, co-developed over 18-42 months, and cannot be swapped without complete redesign.

You can’t see this on a balance sheet. But it’s the death of commodity memory, at least at the high end. Memory has become a platform component, like an integrated graphics chip or a neural processing unit. It’s designed in, qualified over years, and locked to specific customers and products.

The switching costs aren’t just contractual anymore. They’re architectural. The books aren’t just on different shelves—they’re written in different languages, and you need to train the librarians from scratch to read them.

What’s Actually Happening

Management commentary provides the clearest window into these dynamics. Micron’s earnings progression over five quarters tells the story:

Q1 FY2025 (Dec 2024): Revenue $8.7B, gross margin 39.5%

Q4 FY2025 (Sep 2025): Revenue $11.3B, gross margin 45.7%

Q1 FY2026 (Dec 2025): Revenue $13.6B, gross margin 56.8%

Q2 FY2026 (Guidance): Revenue $18.7B, gross margin 68%

That’s not linear recovery—it’s acceleration. Revenue growing 21% then 38% quarter-over-quarter. Margins expanding 11 percentage points, then another 11 points.

The Q1 FY2026 earnings call included this language:

“Industry demand is greater than supply for both DRAM and NAND... we expect these conditions to persist beyond calendar 2026.”

Not “through 2026”—beyond. Precision matters in guidance.

“Completed 100% of calendar 2026 HBM agreements on volume and price.”

Translation: 2026 revenue is locked today. This is qualification lock-in made visible.

“Micron is in the best competitive position in its history.”

From a company that reported negative gross margins eighteen months earlier, this isn’t hype. It’s a company that survived near-death realizing it suddenly has leverage.

Micron raised capex from $18 billion to $20 billion for fiscal 2026, pulled in the Idaho fab timeline (first wafer mid-2027, previously late-2027), and is investing in packaging capacity in Singapore targeting 2027 contribution.

But even with urgency, the timeline is years. The $20 billion being spent in 2025-2026 translates to capacity arriving in 2027-2028. By then, demand will have grown another 2-3 years at 20-40% annually, the HBM cannibalization effect will have intensified, and we’ll need another wave of investment.

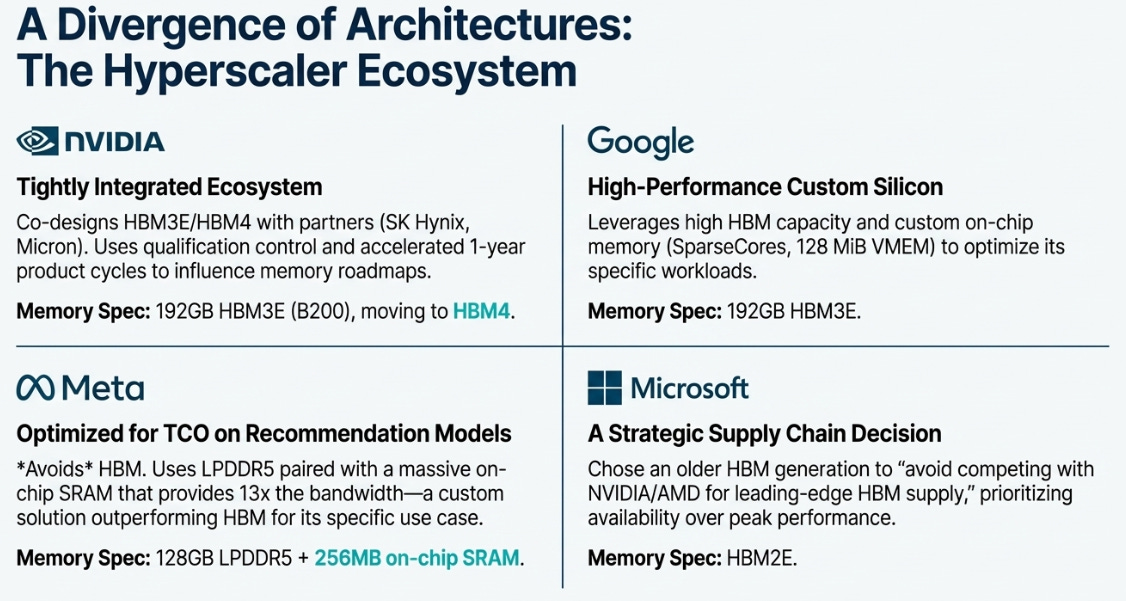

Who Has Leverage

The three-body problem affects different players differently.

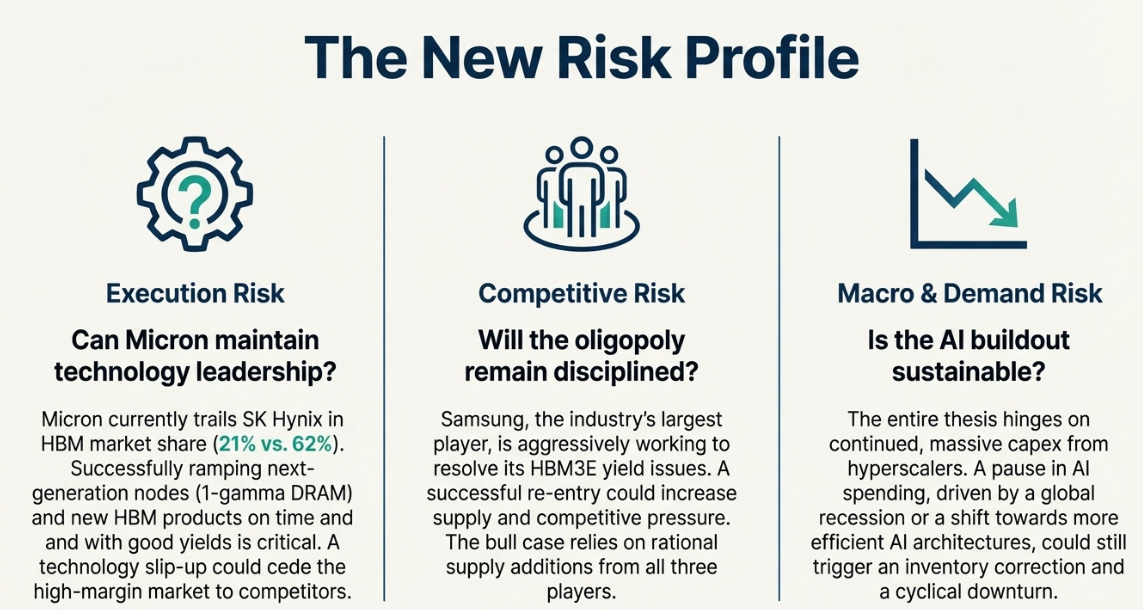

SK Hynix holds 62% HBM market share, primarily from being NVIDIA’s main supplier. They qualified HBM3E early enough to lock in Hopper (H100) and Blackwell (B100/B200) production. They were first to 12-high HBM3E stacks, first to demonstrate 16-high.

The risk is concentration. If NVIDIA represents ~60% of their HBM revenue, any NVIDIA slowdown hits them hard. But right now, being the primary supplier to the dominant AI accelerator is the position everyone wants.

Samsung is the world’s largest DRAM producer (42% overall share) but only 21% of HBM. Despite massive scale and vertical integration, they lagged in HBM3 qualification. Yield issues delayed their qualification for NVIDIA’s H100. By the time they fixed it, SK Hynix and Micron had secured allocation.

By late 2025, Samsung announced 90%+ yields on HBM4 logic dies. They’ve addressed the technical issues. But in a qualification-driven market, being 12-18 months late means missing an entire product generation. Catching up is hard.

Micron is smallest of the three (23% DRAM share, ~16% HBM). They’re compensating with positioning. Their HBM3E is qualified for NVIDIA Blackwell. They’ve secured what management calls a “third HBM customer” (likely AMD MI300). Rather than concentrating like SK Hynix, they’re diversifying across NVIDIA, AMD, and potentially hyperscalers.

The differentiation is geopolitical. As the only U.S.-based memory manufacturer, Micron represents “secure supply” for government and defense. In a bifurcated world, being the domestic producer has strategic value beyond economics.

Execution matters too. Management noted 2025 is a “record year for quality measures.” In a market where qualification delays cost billions in lost revenue, quality and speed create moats.

What The Market Is Missing

The market is pricing Micron at 27× trailing earnings because it sees a cyclical peak. The physics suggests a structural plateau.

At the current price of $286.67, the forward P/E is approximately 14× based on consensus 2026 estimates. That’s higher than the 7-8× typical of commodity memory peaks, which suggests the market is beginning to price in some durability. But it’s still heavily discounting the possibility that this time is fundamentally different.

But here’s what would prove me wrong this time:

If CoWoS lead times compress from “sold out 2+ years” to 12-18 months by mid-2026, the packaging bottleneck is clearing faster than expected. If management language shifts from “beyond 2026” to “near-term tightness” in Q3 or Q4 2026 guidance, they’re seeing demand weakness. If hyperscalers start cutting AI capital expenditure 20%+ in 2026-2027, the infrastructure build-out is reaching “sufficient” levels. Any of those would signal the old cycle reasserting.

But if the three forces persist—and increasingly, the evidence suggests they will—then we’re looking at a different kind of market structure.

The Bull Case: Memory Becomes Infrastructure (40% probability)

If CoWoS bottlenecks extend through 2028, autonomous vehicles scale faster (5M+ deployed by 2028 with 60GB+ each), and video AI achieves mainstream adoption (billions of daily generations), then margins could stabilize at 50-55% with revenue growth of 12-15% annually.

The case for higher probability: The recent $286 stock price (+15% in weeks) suggests the market is beginning to reprice the duration of the shortage. More importantly, the 3:1 HBM cannibalization ratio is worsening as AI demand accelerates—meaning the DDR5 shortage intensifies even as total capacity grows. This is the non-linear dynamic that breaks historical patterns.

FY2029 EPS: $25-28 Fair value at 15-17×: $420-480

The Base Case: Structural Shift With Moderation (45% probability)

The shortage persists through 2027 as bottlenecks clear on their respective timelines. CoWoS packaging expands to 120,000 wafers/month by late 2027. Idaho and other new fabs come online 2027-2028.

Revenue CAGR FY2026-FY2029: 8-10% Gross margins: Moderate from 68% peak to 42-48% sustained (vs. 35-40% historical) Through-cycle margins reset higher due to co-development and reduced fungibility FY2029 EPS: $18-20 Fair value at 14-16× earnings: $280-320

At $286, we’re at the lower end of base case fair value.

The Bear Case: Cycle Reasserts (15% probability)

AI efficiency gains reduce memory intensity 30-40%. Model compression, sparsity techniques, better algorithms all cut memory per inference. CoWoS bottleneck clears by late 2026. Hyperscaler capex moderates 2026-2027.

Revenue CAGR: 0-3% Gross margins: Revert to 30-38% FY2029 EPS: $8-12

Fair value at 12-15×: $140-180

The bear case probability has declined because the evidence keeps mounting that the three bottlenecks are real and persistent. Each quarterly report that maintains “beyond 2026” language, each packaging capacity announcement that remains below demand, each new HBM qualification that takes 18+ months—all reinforce that this isn’t behaving like previous cycles.

At $286, that implies 18% upside to expected value. Not dramatically undervalued, but reasonable given the structural changes underway.

Here’s what I’m watching:

On demand: Are LLM context windows actually moving to 1M tokens in production? Is video AI scaling from demos to deployment? Are autonomous fleets growing or stalling?

On supply: What’s happening to CoWoS lead times? Who’s winning qualification for 2026-2027 products being designed now? Are new fabs hitting their 2027-2028 timelines?

On geopolitics: Are export controls tightening or easing? Is China making unexpected progress on advanced memory? Are CHIPS Act investments translating to actual capacity?

The physics is already set. The three forces—demand explosion, multi-year supply response, geopolitical fragmentation—are operating on different clocks. The pricing is just catching up. And in the meantime, the companies that control the access—the SK Hynixes and Microns of the world—get to write their own terms.

The Library Again

In 1985, when Intel exited DRAM, the lesson was: don’t compete in commodities. Memory was the books on the shelf—important but interchangeable. Value was in the processor, the “researcher” doing the reading.

For forty years, that held. Memory was cheap, abundant, and improving fast enough to keep processors fed. The constraint was always compute.

Then AI showed up with a million researchers all trying to read simultaneously. Suddenly the books on the shelf weren’t enough—you needed librarians who could fetch them instantly. But there weren’t enough librarians. And training new ones took years.

So the entire library is being redesigned. The books are being moved onto the researcher’s desk (HBM integrated on-package). The librarians are being trained in custom filing systems (qualification). And new librarians can’t just walk in off the street—they need 18-42 months of specialized training.

The constraint moved from reading to fetching. And when constraints move, power moves.

The library hasn’t run out of books. It’s run out of access. And access, when you have enough researchers demanding it, is worth more than the books ever were.

Disclaimer:

The content does not constitute any kind of investment or financial advice. Kindly reach out to your advisor for any investment-related advice. Please refer to the tab “Legal | Disclaimer” to read the complete disclaimer.