Oracle 2QFY26 Earnings: The Capital Chasm

A $523B AI backlog, a 43% CapEx surprise, and why Oracle’s tollbooth now looks like a turnpike under construction.

TL;DR

The demand is real, the cash isn’t (yet): Oracle has built a strategically valuable “AI tollbooth” at the junction of enterprise data and large models, with a record $523B in contracted revenue and explosive multi-cloud database growth.

From software margins to concrete economics: To monetize that backlog, Oracle must spend like an infrastructure builder, not a software vendor, CapEx guidance just jumped 43%, free cash flow swung to –$10B for the quarter, and the Ampere sale looks more like balance-sheet triage than tidy “chip neutrality.”

Three futures, one financing problem: The path from here ranges from “funded platform” to “leveraged utility” to “Global Crossing redux,” and with no concrete funding plan, widening CDS spreads, and opaque OCI margins, the probability mass is drifting away from the clean AI-compounder outcome.

In 1998, James Crowe had a vision. The founder and CEO of Level 3 Communications believed that internet traffic would grow so explosively that the world would need entirely new infrastructure to carry it — not upgrades to existing telephone networks, but purpose-built fiber optic highways spanning continents. He wasn’t wrong. Internet traffic was doubling every hundred days. The demand was obvious to anyone paying attention.

So Level 3 raised billions and started digging. They laid fiber across North America, under the Atlantic, through Europe. They signed contracts with the nascent internet companies that would need all that bandwidth. By 2000, Level 3 had over $6 billion in contracted future revenue and a stock price that valued them as the backbone of the digital economy. The thesis was elegant: own the pipes, charge the tolls, compound forever.

Global Crossing ran the same playbook, with even more ambition. Gary Winnick, their founder, built a network spanning four continents. They went public in 1998 and within two years had a market cap exceeding $50 billion. Fortune called Winnick “the new telecom titan.” The contracts were real. The demand was real. The technology worked.

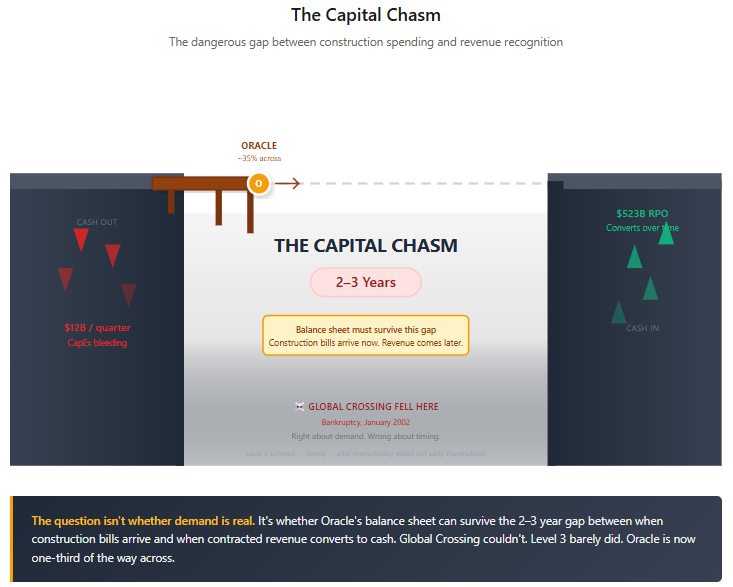

What Crowe and Winnick got wrong was the timing — specifically, the mismatch between when construction bills came due and when revenue arrived. Fiber optic networks require massive upfront capital: digging trenches, laying cable, building switching stations, lighting the fiber. The bills arrive quarterly, sometimes monthly. But the revenue comes later, and slowly — you sign a contract, then the customer gradually ramps usage over years. In infrastructure, you pay for the road before anyone drives on it.

By 2001, Level 3’s debt was trading at sixty cents on the dollar. By 2002, Global Crossing was bankrupt — the fourth-largest bankruptcy in American history at the time. The internet kept growing. Traffic eventually filled those fiber optic cables many times over. But Global Crossing’s shareholders didn’t benefit. The bondholders took the company through restructuring, wiped out equity, and emerged owning infrastructure that ultimately proved valuable. Level 3 survived, barely, through a brutal restructuring that destroyed early investors.

I’ve been thinking about this history because Oracle just reported earnings that crystallized a pattern I’d been sensing but hadn’t fully articulated. The company announced $523 billion in contracted future revenue — the largest backlog in enterprise technology history. The demand is real. The technology is differentiated. The contracts are signed.

And the stock dropped 11% after hours.

This is the Capital Chasm: the dangerous period where a company transforms from a high-margin service provider into a capital-intensive infrastructure builder, betting everything on the assumption that revenue will catch up to construction costs before the balance sheet breaks. Level 3 and Global Crossing fell into this chasm. Oracle is now staring into it.

The Ninety Days That Changed Everything

To understand why the market reacted so violently to what was, on the surface, a strong earnings report, you have to trace the narrative arc of the last three months.

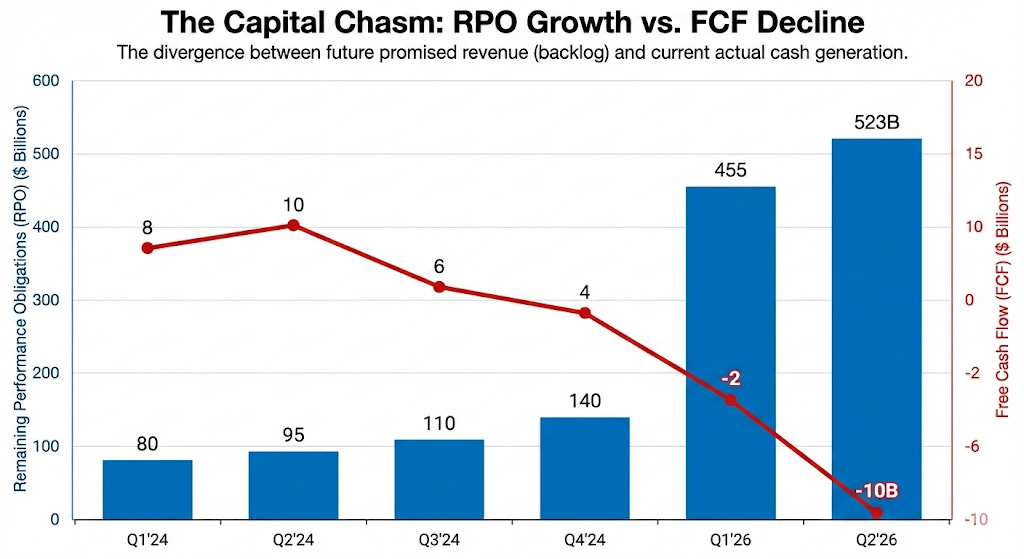

In September, Oracle reported first quarter results that genuinely shocked Wall Street. Remaining Performance Obligations (RPO), the accounting term for contracted future revenue, had surged to $455 billion, up from $138 billion just a few quarters earlier. This wasn’t incremental growth; it was a step-function change driven by massive AI infrastructure deals with OpenAI, Microsoft, and NVIDIA.

The thesis that emerged from that earnings call was elegant, and I found it compelling. Oracle controlled something uniquely valuable: decades of enterprise data locked in Oracle databases across the Fortune 500, governed by compliance frameworks that couldn’t easily be replicated. As companies rushed to deploy AI, they needed that data — but they couldn’t just dump it into ChatGPT. They needed a secure junction point where enterprise data could meet artificial intelligence under proper governance. Oracle, the argument went, had built exactly that junction point. They were the AI tollbooth.

The stock surged from $220 to nearly $345. Analysts scrambled to raise price targets. The narrative was set: Oracle had transformed from legacy database vendor to critical AI infrastructure partner, and the backlog proved it.

Then November happened. Concerns began mounting about the solvency and spending pace of Oracle’s largest customer — OpenAI. Reports circulated about OpenAI’s burn rate, its need for additional funding, its dependence on Microsoft’s continued largesse. If OpenAI couldn’t pay its bills, what was that $455 billion backlog actually worth?

More telling was what happened in the credit markets. Credit Default Swaps on Oracle debt began widening — a signal that bond traders, who tend to be more skeptical than equity investors, were sniffing out risk. The stock quietly round-tripped from $345 back to $223, almost exactly where it had been before the September earnings. The equity market had given back all its gains, but the credit market was saying something worse: the risk profile had fundamentally changed.

Which brings me to yesterday’s earnings call.

What the Call Revealed

The headline numbers told a story of continued strength. RPO grew another 15% sequentially to $523 billion. Cloud infrastructure revenue was up 68% YoY. Multi-cloud database consumption, Oracle’s strategy of embedding its database inside AWS, Azure, and Google Cloud data centers, grew 817%. “Our fastest growing business,” CEO Clay Magouyrk noted.

The tollbooth, in other words, is working. The fees are being collected. The strategic thesis I outlined in September remains intact.

But the call revealed something else — something that explains why the stock cratered despite the strong demand metrics. It came during the Q&A, when analyst after analyst pressed management on a simple question: how are you going to pay for all this?

Here’s CFO Doug Kehring’s response to one such question:

“We have a variety of sources available to us to fund the business. We have access to the public debt markets. We have access to bank debt. We have access to private markets. And then also there are, as Clay mentioned, some different models for different types of customers that can help from a capital perspective as well... We are committed to maintaining our investment grade rating.”

What strikes me about this answer is everything it doesn’t say. No numbers. No timeline. No specifics about how much capital Oracle actually needs to raise. Just reassurance that various options exist and a commitment to a credit rating, which is the kind of thing you emphasize when you’re worried about it.

Magouyrk, for his part, suggested that analyst models were too pessimistic:

“I wouldn’t assume that we would have to spend as much as I’ve seen some people try to put together in spreadsheets.”

This is not a funding plan. This is hope dressed as strategy. The credit market heard it clearly, CDS spreads widened further after the call.

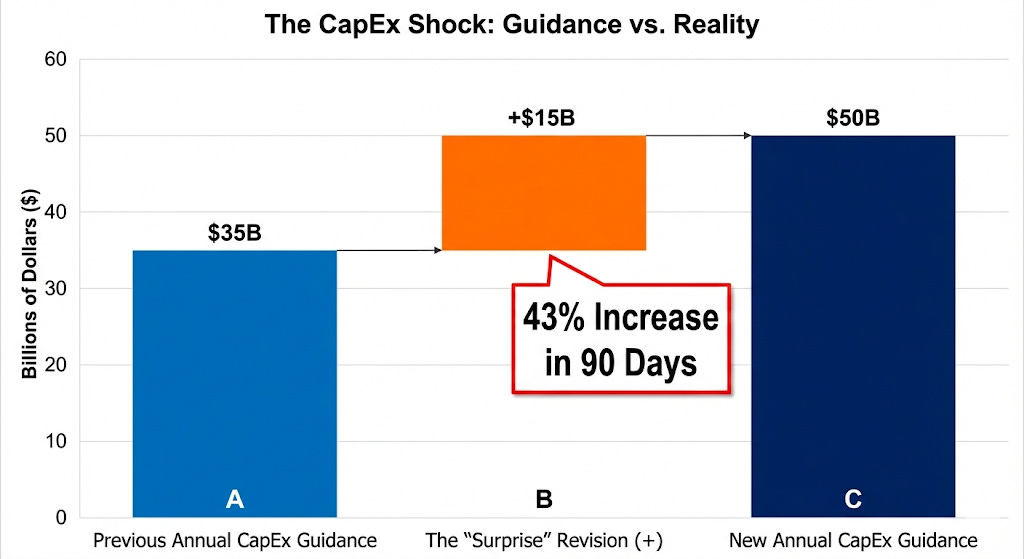

What the numbers actually showed was alarming. Capital expenditure hit $12 billion in the quarter, 45% above what analysts expected. Free cash flow was negative $10 billion, in a single quarter. And management raised full-year CapEx guidance by $15 billion, from roughly $35 billion to approximately $50 billion. That’s a 43% revision to a major guidance item just three months after they set it.

To put this in perspective: when your CapEx forecast has a 43% error band over ninety days, you don’t have a forecast. You have a guess. And when your guess is wrong by $15 billion to the upside, the market reasonably wonders what else you’re underestimating.

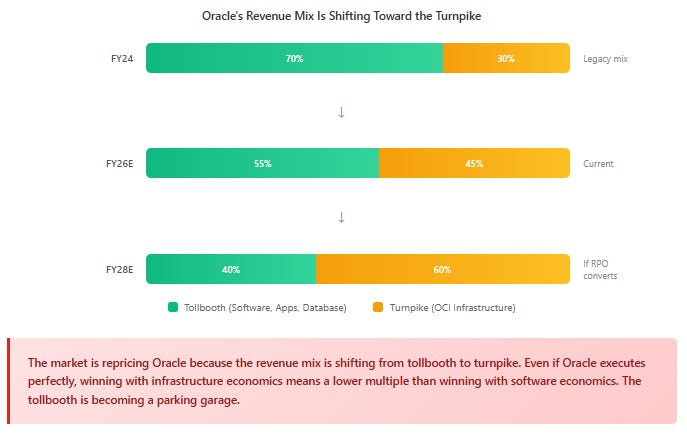

The Tollbooth and the Turnpike

I need to revisit my own thesis here, because I got something importantly wrong.

What I got right was the strategic positioning. Oracle has genuinely built something valuable at the intersection of enterprise data and artificial intelligence. The multi-cloud distribution strategy — embedding Oracle infrastructure inside competitors’ clouds — is working, as that 817% growth figure demonstrates. The database moat, which many had written off as legacy technology, turns out to be perfectly suited for the AI era, where governed access to structured enterprise data is exactly what companies need. The tollbooth exists, and it’s collecting fees.

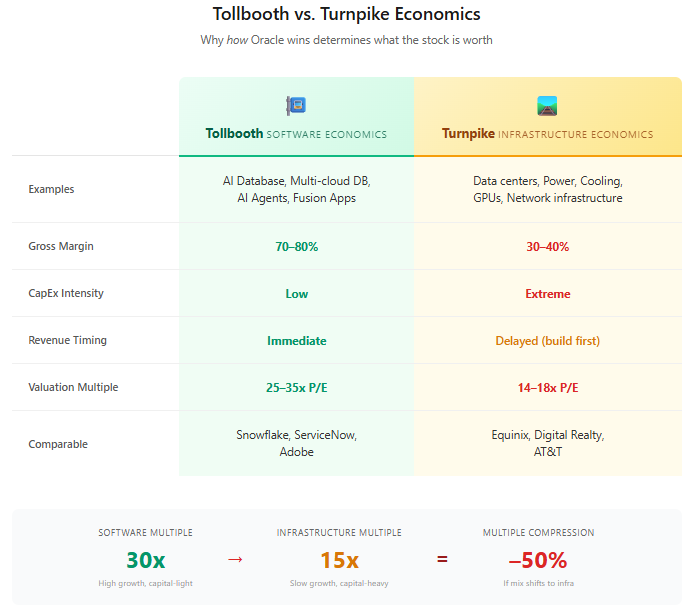

What I got wrong was the capital intensity of getting traffic to that tollbooth. I had modeled Oracle as a gatekeeper — a high-margin software business that would benefit from AI without having to build the underlying infrastructure. That was wrong. To capture the AI opportunity, Oracle is being forced to become a construction company.

The tollbooth (database services, AI agents, multi-cloud distribution) is indeed high margin. But to get traffic to the tollbooth, Oracle must build the turnpike — the data centers, power infrastructure, cooling systems, and GPU clusters that AI workloads require. And turnpikes are expensive. The $523 billion in contracted revenue doesn’t flow to Oracle automatically; it flows only after Oracle spends tens of billions building the infrastructure to deliver it.

This is precisely the trap that killed Global Crossing. They had the contracts. They had the demand. They had the technology. What they didn’t have was the balance sheet to survive the gap between construction spending and revenue recognition. Oracle is now in that gap.

The Ampere Tell

One moment from the quarter crystallized this for me: the Ampere sale.

Oracle announced it had sold its stake in Ampere Computing, the ARM-based chip company, for a $2.7 billion gain. Ellison framed this as strategic clarity, a pivot to “chip neutrality” that would allow Oracle to deploy whatever silicon its customers preferred rather than being locked into proprietary designs.

“We no longer think it is strategic for us to continue designing, manufacturing and using our own chips,” Ellison explained. “We are now committed to a policy of chip neutrality.”

On the surface, this makes sense. Oracle cannot out-innovate NVIDIA. Being chip-agnostic gives them flexibility.

But consider the timing. Oracle sold a strategic asset — their vertical integration play, their hedge against NVIDIA dependency, in the same quarter where free cash flow was negative $10 billion and they needed to revise CapEx guidance upward by 43%. The $2.7 billion gain conveniently propped up both GAAP and non-GAAP earnings per share, allowing management to claim a “beat” on a quarter that would otherwise have looked ugly.

A company flush with cash doesn’t sell strategic assets in the middle of an AI boom. Ampere represented years of investment and a genuine competitive differentiator. Oracle sold it for 2.7% of this year’s CapEx budget. That’s not pivoting to chip neutrality. That’s pawning the jewelry to make rent.

There’s another element of the call that troubles me. Magouyrk discussed alternative financing models with surprising enthusiasm:

“We have some other interesting models... One of them is that customers can actually bring their own chips... Similarly, we have different models where some vendors are actually very interested in a model where they rent their capacity rather than selling that capacity.”

What he’s describing is a fundamental transformation of Oracle’s business model. If customers bring their own chips and Oracle provides only the building, power, and cooling, Oracle isn’t a cloud provider anymore. They’re a data center REIT: a landlord.

The valuation implications are severe. Cloud providers trade at 25-35x earnings because they capture the full margin stack on compute. Data center REITs like Equinix and Digital Realty trade at 14-18x because they’re capital-intensive, slow-growing, and their margins are bounded by the commodity nature of their offering. The market is re-rating Oracle because it fears the tollbooth is becoming a parking garage.

Three Paths Forward

Which brings me to where we are now. The question facing Oracle investors is no longer “is demand real?” — the $523 billion backlog answers that decisively. The question is whether Oracle can finance the construction of the turnpike without destroying shareholder value in the process.

I see three scenarios, and the Level 3/Global Crossing parallel helps frame each one.

The first scenario is what Level 3 dreamed of: funded construction leading to monetized demand. Oracle secures project financing or strategic investment at reasonable terms. Perhaps a sovereign wealth fund takes a stake. Perhaps Oracle successfully issues debt at manageable rates. The construction continues, RPO converts to revenue at 35% or more annually, and by late fiscal 2027, free cash flow turns positive. The margin profile improves as initial construction costs fade and the high-margin software tolls, AI Database services, governed inference, multi-cloud distribution, begin scaling. The stock re-rates to $400 or higher.

I put the probability of this scenario at roughly 25%, down from my estimate of 35% before this earnings report. The reason for my reduced confidence is management’s inability to articulate a credible funding plan. You can’t build toward a positive outcome when you won’t specify how you intend to get there.

The second scenario is AT&T’s reality: survival as a utility rather than triumph as a platform. Oracle secures funding, but at a cost — elevated interest rates, restrictive covenants, perhaps dilutive equity issuance at unfavorable prices. The RPO converts, but margins remain compressed because infrastructure economics dominate the revenue mix. The company survives and grows, but trades like a leveraged utility rather than a software compounder. The multiple compresses to 18-22x; the stock grinds between $250 and $350 for two or three years while the balance sheet heals.

This is probably the most likely outcome, at perhaps 40% probability. It’s not a disaster, but it’s not the AI tollbooth story that drove the stock to $345, either. Investors who bought the growth narrative end up owning an infrastructure utility.

The third scenario is Global Crossing’s fate: right thesis, fatal timing. OpenAI renegotiates its commitments as AI compute costs fall — model efficiency improvements are real, and inference costs are declining rapidly. Or power procurement delays strand billions of dollars in unfinished data centers. Or credit markets tighten and Oracle can’t refinance at reasonable rates. CapEx continues ballooning while revenue growth lags (as it did this quarter, where revenue missed despite the RPO growth). Rating agencies downgrade Oracle’s debt. The company is forced into a dilutive equity raise at $150-180, and the multiple permanently compresses to telecom levels.

I put this probability at 35%, up significantly from 20% before this report. The reason is simple: management’s non-answer on funding, combined with the Ampere sale and the CapEx guidance revision, suggests the balance sheet is under more stress than they’re admitting.

What I’m Watching

Three metrics will determine which scenario plays out.

The first is funding clarity. Oracle needs to articulate an actual plan with actual numbers. Not “a variety of sources” and “commitment to investment grade,” but specific guidance on how much capital they intend to raise, in what form, and on what timeline. If CDS spreads continue widening, or if rating agencies move to a negative outlook, the market will force an answer Oracle doesn’t want to give.

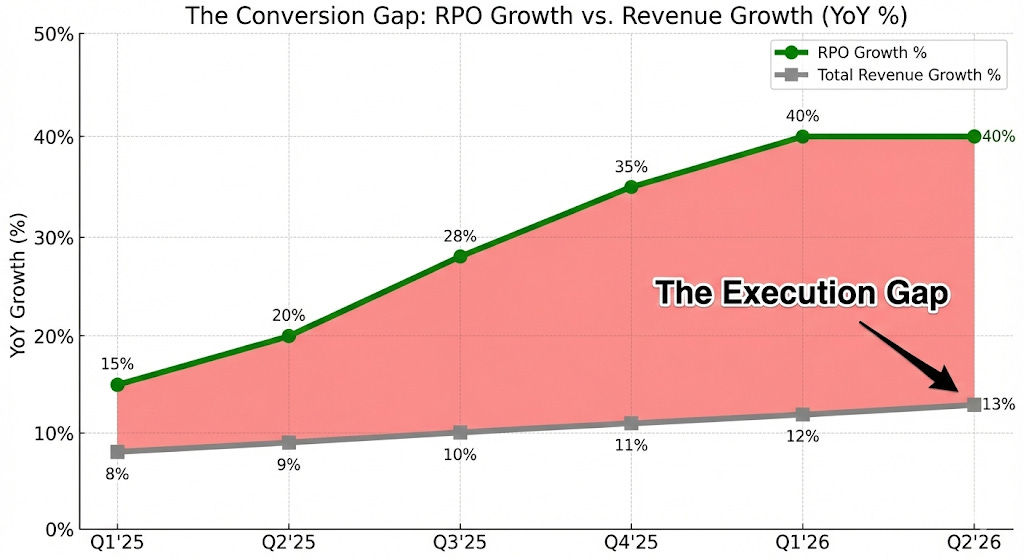

The second is what I’m calling the conversion gap. RPO due within twelve months grew 40% YoY, but total revenue grew only 13% in constant currency. That 27-point spread between booked demand and recognized revenue is the measure of execution. It tells you whether Oracle can actually build fast enough to bill what they’ve sold. If that gap doesn’t narrow meaningfully by the fourth quarter, the market will conclude that Oracle can sign contracts but can’t deliver on them.

The third is margin disclosure. Management has steadfastly refused to break out gross margins for OCI, Oracle’s infrastructure cloud. This is not normal — every other cloud provider discloses segment margins. The continued silence almost certainly means OCI margins are worse than the blended corporate number, and management doesn’t want to highlight the mix shift toward lower-margin infrastructure revenue. Any disclosure, even directional, of how quickly new AI data centers reach the 30-40% gross margin range Magouyrk referenced would help. Continued silence is its own answer.

Conclusion

Level 3’s bondholders eventually made money. The fiber got lit, the traffic came, and the infrastructure proved valuable. Global Crossing’s bondholders made money too — after wiping out equity holders in bankruptcy and emerging with ownership of assets that the original shareholders had paid to build.

The difference between these outcomes wasn’t demand. Both companies correctly predicted that internet traffic would explode. The difference was financing structure — specifically, whether the balance sheet could survive the gap between construction and monetization.

Oracle has found the same junction point in the AI era that the fiber carriers found in the internet era. The tollbooth is real. The multi-cloud distribution is working. The backlog is unprecedented, larger than any enterprise technology company in history. Larry Ellison’s bet on AI infrastructure looks strategically correct.

But the turnpike is only half-built. The construction budget just blew out by 43% in a single quarter. Management won’t say how they intend to pay for the asphalt. And the bond market, which has seen this movie before, is pricing in meaningful probability that equity holders end up like Global Crossing’s, owning shares in a company that was right about the destination but ran out of gas on the highway.

The tollbooth is still collecting tolls. The question for shareholders is whether they’ll own the road when the traffic arrives, or whether the bondholders will.

Disclaimer:

The content does not constitute any kind of investment or financial advice. Kindly reach out to your advisor for any investment-related advice. Please refer to the tab “Legal | Disclaimer” to read the complete disclaimer.