Ping An: The Trust Bundler

What a collapsing salesforce reveals about the future of Chinese finance

TL;DR

Ping An didn’t lose its agents—it replaced what they sold. A 74% reduction in salesforce looks like collapse, but evidence suggests trust has shifted from door-to-door selling to bundled healthcare and retirement services.

The market prices opacity, not failure. At ~0.65× Embedded Value, investors are discounting balance-sheet uncertainty and management silence, not the operating turnaround in Life & Health.

This is an asymmetric wait. Base-case returns are dividend-led and pedestrian; the upside hinges on capital deployment and buybacks that signal belief in the service-utility model.

In October 2025, Ping An Insurance of China reported third-quarter results that crystallized a question investors have been avoiding: was the agent collapse a crisis, or a strategy?

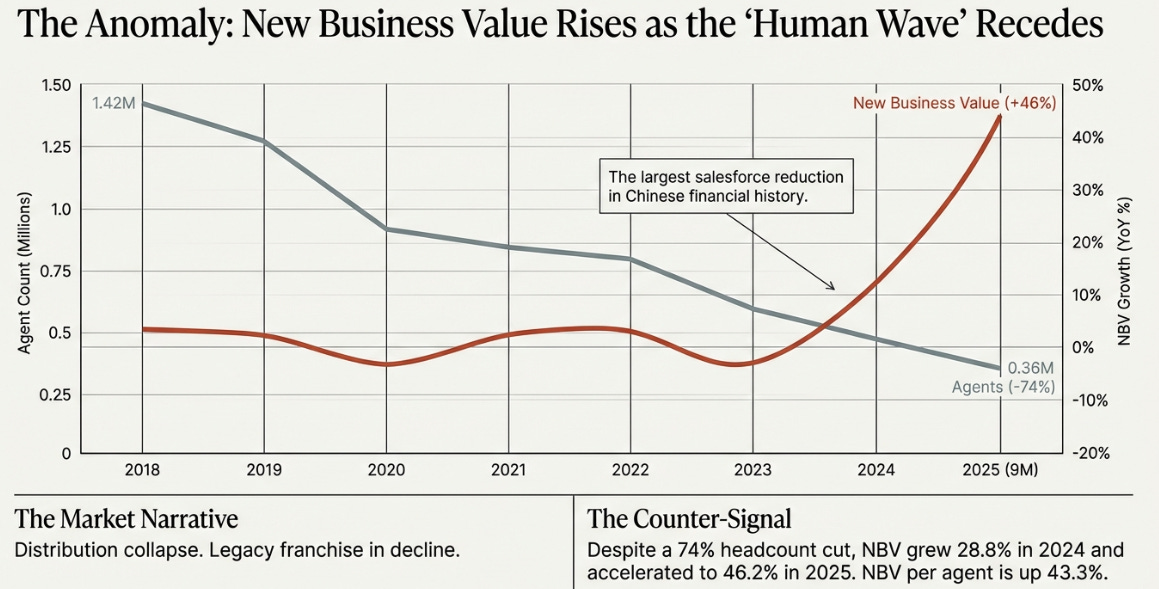

The numbers suggested the latter. New business value up 46% YoY, despite 74% fewer agents than six years prior. Bancassurance up 171%. Customers eligible for health services contributing 70% of new business value.

But the stock barely moved. It still trades at 0.65x Embedded Value—distress pricing for a franchise supposedly in turnaround. Either the market doesn’t believe the numbers, or it’s pricing something else entirely.

The question is whether this quarter is the inflection point or just another data point in a long, slow grind.

To understand which, we need to start with an encyclopedia salesman in 1985.

The Salesman

In that year, an Encyclopedia Britannica salesman would pull into a suburban driveway, briefcase in hand, ready for a two-hour pitch. He wasn’t selling books. He was selling a parent’s anxiety about their child’s future.

The product itself was almost beside the point. Twenty-four leather-bound volumes, updated annually, containing the sum of human knowledge—how could a middle-class family possibly evaluate whether it was worth $1,400? They couldn’t. The information asymmetry was total. And that asymmetry was precisely what made the salesman essential.

His job was to bridge the trust gap. He would sit in the living room, show the gold-embossed spines, flip to an entry on the solar system or Abraham Lincoln, and make the intangible tangible. He would offer a payment plan. He would invoke the children’s college prospects. He would make a complex, consequential, once-in-a-decade purchase feel safe.

Britannica’s business model was not, in any meaningful sense, a publishing business. It was a direct sales business that happened to sell books. The company employed 2,000 door-to-door salespeople in North America alone. Commissions ran as high as 50% of the sale price. The salesforce was not a cost center to be optimized; it was the entire mechanism by which a complicated product reached customers who couldn’t evaluate it themselves.

Then came the internet.

The standard narrative is that Wikipedia killed Britannica by making information free. This is true but incomplete. Wikipedia made information free, but Google made information findable. And once you could find any fact in seconds, the elaborate trust-bridging ritual of the encyclopedia salesman became not just unnecessary but absurd.

By 2012, Britannica stopped printing physical encyclopedias. A 244-year-old institution, ended. The obituaries focused on the content. But the real story was the distribution model. The internet didn’t kill the encyclopedia. It killed the salesman.

Between 2018 and 2024, Ping An’s life insurance agent count collapsed from 1.42 million to 363,000. That’s not a reduction. That’s a 74% annihilation of the salesforce, the largest in Chinese financial history.

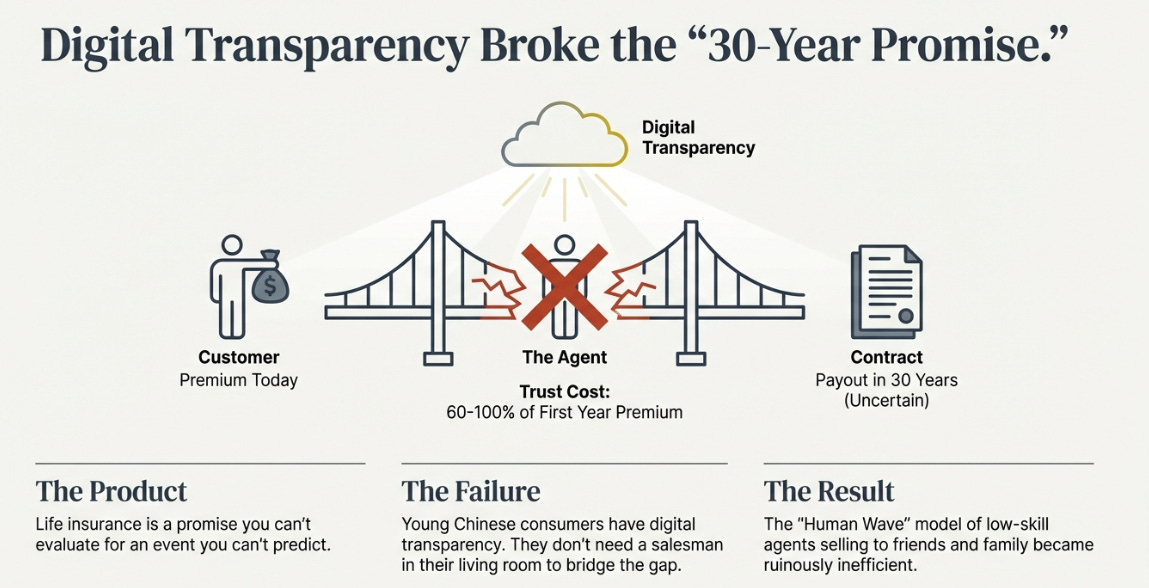

For decades, Chinese life insurance operated on what the industry calls the “human wave” model: hire massive numbers of low-skill agents, train them minimally, send them to sell complex financial promises to friends and family. The agents didn’t understand the products. The customers didn’t understand the products. But the agents bridged the trust gap, just like the Britannica salesman, and policies got sold.

Then came digital transparency, economic slowdown, and demographic shift. Young Chinese consumers don’t answer the door for salespeople. They compare products on their phones. The trust-bridging ritual stopped working.

Here’s what the market sees: 1.1 million agents vanished, 0.65x Embedded Value, a Chinese financial conglomerate with opaque property exposure. Distribution collapse. Legacy franchise. Sell.

Here’s what I see: the same 1.1 million agents, but as a cost line that just got cut by 74%. The same 0.65x EV, but pricing zero probability of the service model working. The same property exposure, but disclosed at 3.5% of the portfolio—smaller than the fear implies.

One of us is wrong. At 4.2% dividend yield, you get paid to find out which.

The Pivot

To understand what Ping An might actually be doing, you have to understand what the salesforce actually did.

The life insurance agent didn’t sell policies. She sold trust.

Think about what a life insurance policy actually is: a 30-year promise, from a company you can’t meaningfully evaluate, to pay money upon an event you can’t predict, at a price you have no way to verify is fair. The information asymmetry is almost total. The customer is being asked to hand over money today in exchange for a piece of paper that might—or might not—be worth something decades from now.

This is, to put it mildly, a hard sell. And the agent’s job was to make it feel safe. She would sit in your living room, explain the policy in simple terms, tell you about her own coverage, invoke your children’s future. She bridged the gap between your inability to evaluate the product and your need to buy it anyway.

The problem is that bridging trust is expensive. First-year commissions in Chinese life insurance run 60-100% of the premium. The customer pays, the agent takes the majority, and the insurance company hopes to make it back over the next 29 years. This model works when you have no alternative. It becomes ruinously inefficient when you do.

Ping An’s insight, and I think it is a genuine insight, is that there’s a better way to create trust than paying a salesman to sit in someone’s living room.

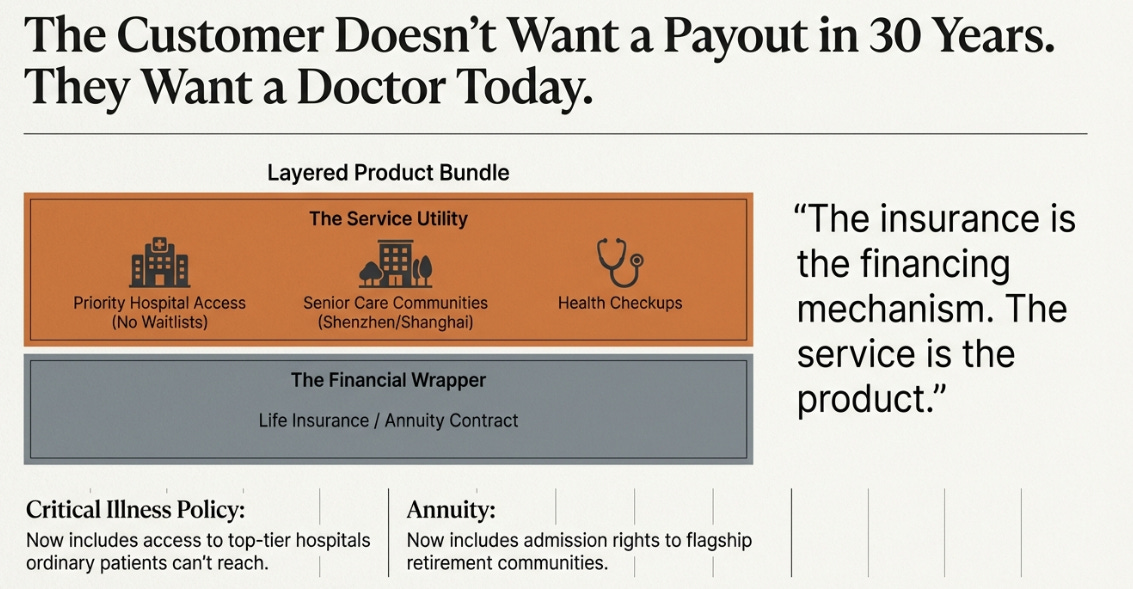

The customer doesn’t want a payout in 30 years. They want a doctor today.

Consider what Ping An actually sells now. A critical illness policy doesn’t just promise money if you get cancer. It comes with priority appointments at China’s top hospitals, the ones with six-month waiting lists that ordinary patients can’t access. An annuity product doesn’t just promise retirement income. It comes with admission rights to Ping An’s retirement communities, with flagship facilities in Shanghai and Shenzhen scheduled to open in the second half of 2025.

The insurance is the financing mechanism. The service is the product.

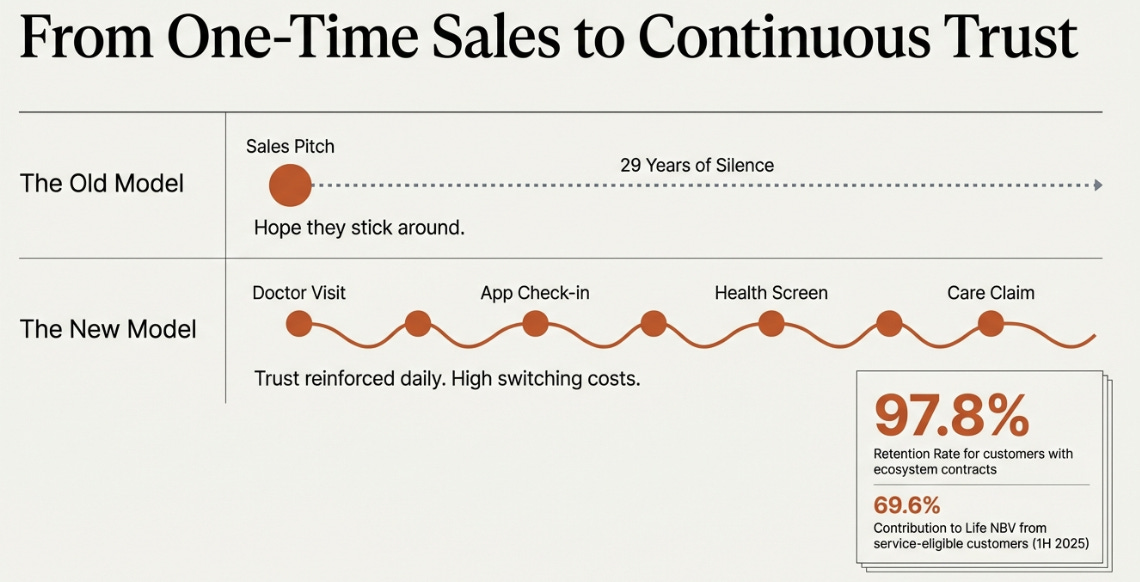

This is not a small distinction. The old model acquired customers through a one-time trust-bridging event (the sales pitch) and then hoped they stuck around. The new model acquires customers through ongoing service delivery that creates trust continuously. Every doctor’s appointment, every health check-up, every interaction with the senior care network reinforces the relationship.

The evidence suggests this is working. Customers eligible for Ping An’s health and senior care service benefits contributed 69.6% of life insurance new business value in the first half of 2025. Customers holding four or more Ping An contracts exhibit 97.8% annual retention. And despite 74% fewer agents, new business value grew 28.8% in 2024, then accelerated to 46.2% in the first nine months of 2025. NBV per agent rose 43.3% in 2024 alone.

The bancassurance channel tells a similar story. By routing insurance sales through its own bank branches rather than competing for shelf space at third-party banks, Ping An grew bancassurance new business value 62.7% in 2024, then 170.9% in the first nine months of 2025.

This isn’t an industry-wide phenomenon. China Life’s agent count has also fallen, but without comparable productivity gains: their NBV per agent grew just 8% in 2024 versus Ping An’s 43%. CPIC is attempting its own reforms, but from a smaller base and with less integrated service infrastructure. The difference is the ecosystem. China Life doesn’t own a bank for captive bancassurance distribution. It doesn’t operate hospitals or retirement communities. It can cut agents, but it has nothing to replace what those agents did. Ping An’s bet is that it does.

The Skeptic

If the service-led model is working, why does the stock trade at distress levels?

Because investors aren’t just valuing the Life & Health business. They’re valuing a group with a complex balance sheet—and they don’t trust what they can’t see.

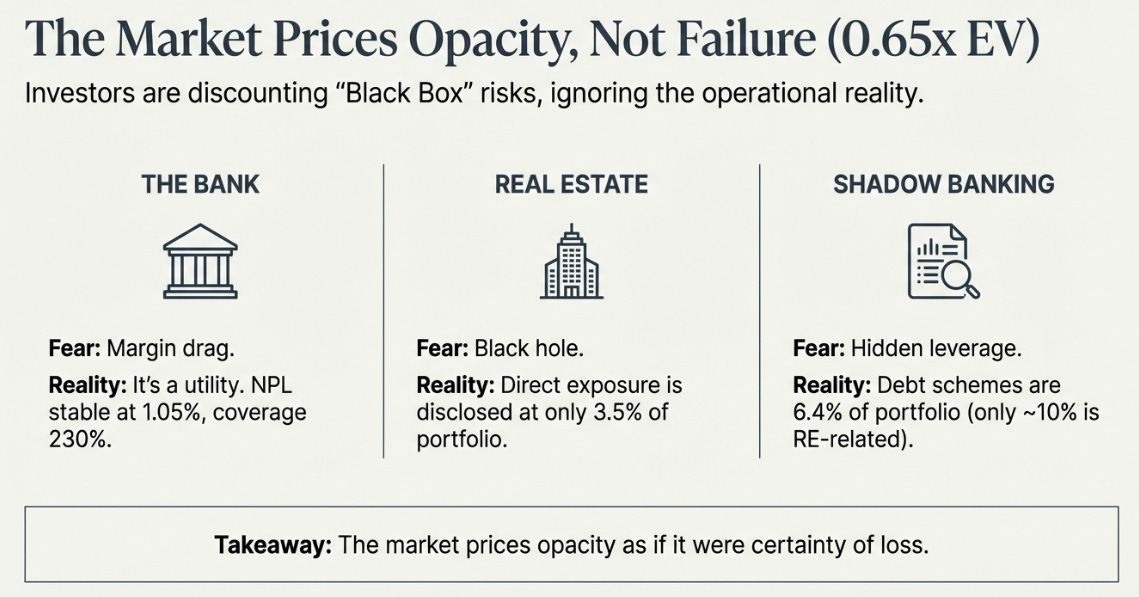

Start with the bank. Ping An Bank contributes roughly 20% of group operating profit and faces persistent net interest margin compression in China’s low-rate environment. But the bank is a utility, not an engine. Its job is distribution and liquidity, not growth. Credit quality has held—NPL ratio at 1.05%, provision coverage at 230%—and the life insurance business is sufficiently profitable to absorb the margin compression. The bank doesn’t need to be a growth story. It needs to not be a crisis. So far, it isn’t.

Then there’s the investment portfolio. Ping An manages over RMB 5.7 trillion in insurance funds. Direct real estate exposure is disclosed at 3.5% of the portfolio. Debt schemes and trust products: the “shadow banking” segment that makes investors nervous—represent 6.4%, of which roughly 10% is real estate-related. These numbers don’t eliminate risk, but they’re smaller than the vague “black box” fears suggest. The market prices opacity as if it were certainty of loss. It might not be.

More subtle is the question of Embedded Value itself. When Ping An reports that its stock trades at 0.65x Embedded Value, that EV is calculated using a 4.0% long-run investment return assumption and an 8.5% risk discount rate. If investors believe the realistic long-run return in China is 3.0-3.5%, the “true” EV is lower: and the discount to it is smaller than it appears. The market may not be ignoring the value. It may be questioning the ruler.

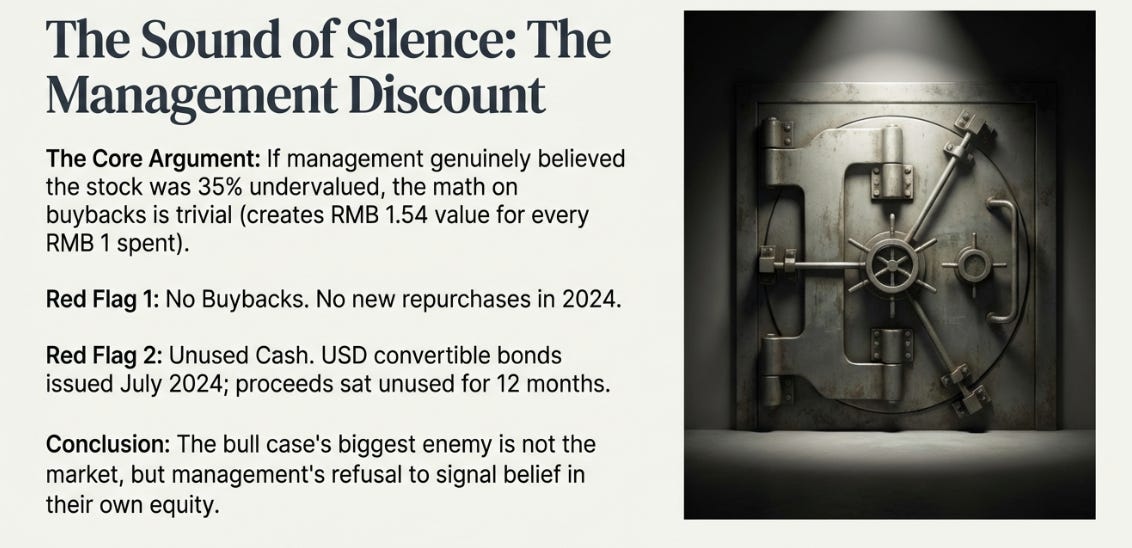

But the most uncomfortable signal is capital allocation. If management genuinely believed the stock was 35% undervalued, the math on buybacks is trivial: every RMB 1 spent repurchasing shares creates RMB 1.54 of value for remaining shareholders. Yet Ping An made no new share repurchases in 2024. The company holds 102.6 million treasury shares from a prior program, but has not added to them.

More striking: in July 2024, Ping An issued USD-denominated convertible bonds. As of June 30, 2025, those proceeds remained unused—cash sitting on the balance sheet for twelve months. You can construct explanations: regulatory constraints, capital preservation for ecosystem buildout, optionality for future stress. All plausible. None confirmed.

The uncomfortable truth is that the strongest piece of evidence against the bull case comes from the people with the best information. The bull case’s biggest enemy is management’s own silence.

The Math

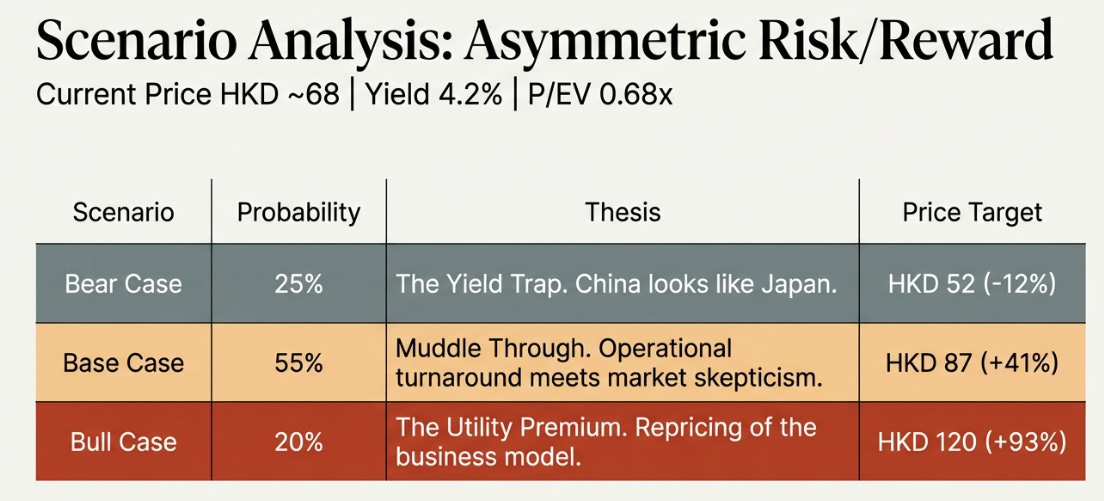

So where does this leave an investor? I see three scenarios.

As of January 2026, Ping An trades at HKD 68.25. Embedded Value per share is approximately HKD 100, implying a P/EV of 0.68x. The forward P/E is 7.3x. The dividend yield is 4.2%.

Bear Case: The Yield Trap

Probability: 25%

China follows Japan’s trajectory. Rates stay low. The 4.0% investment return assumption proves optimistic; actual returns come in at 3.0%. Trust and property exposures crystallize into losses. Dividend cut to preserve capital.

Key assumptions: Revenue CAGR of 0%. NBV growth of just 3% as demand softens. Actual investment returns of 3.0%, well below the 4.0% embedded in EV calculations. Terminal P/EV compresses to 0.50x as the market prices permanent impairment.

2028 Price Target: HKD 52

Total Return: -12%

Base Case: Muddle Through

Probability: 55%

NBV growth normalizes to high single digits as Life & Health continues its quality-over-quantity shift, but the bank drag and muted P&C growth offset headline revenue acceleration. The market never fully trusts Ping An, but the discount narrows slightly as the company proves it isn’t going bankrupt. Investors collect the dividend and wait.

Key assumptions: Revenue CAGR of 4%. NBV growth of 8-10%, supported by the service model but no longer accelerating. Actual investment returns of 3.5-3.8%—below assumption but manageable. Terminal P/EV of 0.75x as skepticism fades but conviction never arrives.

2028 Price Target: HKD 87

Total Return: +41% | Annualized: +12%

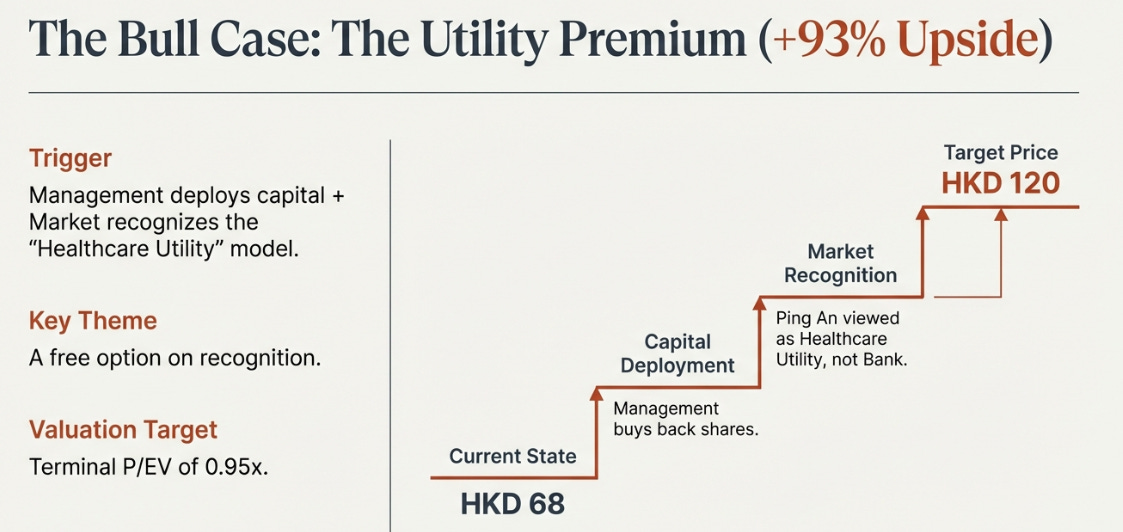

Bull Case: The Utility Premium

Probability: 20%

Management deploys convertible proceeds into healthcare ecosystem and announces meaningful buybacks—the signal that says “we believe in our own value.” Property stabilizes. Foreign capital returns. The market stops seeing Ping An as a leveraged rate bet and starts seeing it as a healthcare utility for an aging population.

Key assumptions: Revenue CAGR of 8%. NBV growth of 15%, sustained by ecosystem expansion. Actual investment returns of 4.0% or better as markets stabilize. Terminal P/EV of 0.95x as the conglomerate discount compresses.

2028 Price Target: HKD 120

Total Return: +93% | Annualized: +24%

Putting it together: The asymmetry looks favorable on paper: +93% upside versus -12% downside. But the bull case requires multiple things to go right simultaneously, while the bear case only requires one thing to go wrong.

The Library

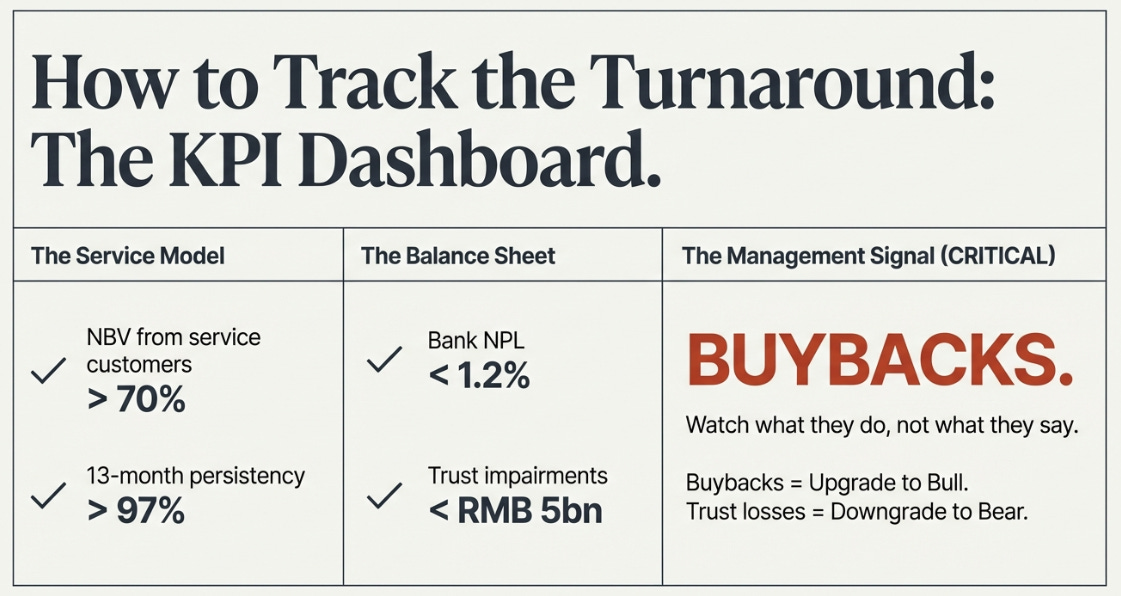

If you own this stock, here’s what to watch.

For the service model: NBV from service-eligible customers above 70%, 13-month persistency above 97%, NBV per agent still rising. If any of these break down, so does the thesis.

For the balance sheet: bank NPL below 1.2%, annual trust impairments below RMB 5 billion. Above those thresholds, the defensive story cracks.

For management intent: buybacks above RMB 20 billion or deployment of the convertible proceeds signals belief. Continued silence signals something else. Watch what they do, not what they say.

The decision rule is simple. Buybacks and capital deployment: upgrade to bull. NPL spike and trust losses: downgrade to bear. Neither: stay base case, collect the dividend, reassess annually.

I keep coming back to Britannica.

The mistake wasn’t the product—the encyclopedia was still useful in 2005. The mistake was believing the salesforce was the business, rather than a solution to a problem. When a better solution emerged, the salesforce went from asset to liability overnight.

Ping An’s bet is that it can see the distinction. The agent solved a trust problem. The healthcare ecosystem solves it better. If that’s true, the 74% agent reduction isn’t a crisis—it’s efficiency.

But here’s the caveat: even if the flywheel is real, the multiple stays capped until the market believes the balance sheet tails are bounded. The variant perception isn’t “the market doesn’t understand.” It’s “the market is pricing uncertainty that might resolve favorably.”

At HKD 68, you collect 4.2% while you wait. Base case: 12% annualized. Bull case: a free option on recognition.

Britannica failed because it insisted its value was the books.

The stock is priced for the books.

The opportunity is the library.

Disclaimer:

The content does not constitute any kind of investment or financial advice. Kindly reach out to your advisor for any investment-related advice. Please refer to the tab “Legal | Disclaimer” to read the complete disclaimer.