Pure Storage: The Direct Flash Divergence

Pure Storage ignored the disk era’s assumptions—and found the cheat code everyone else can’t use.

TL;DR

Enterprise storage optimized around a mechanical constraint that no longer exists, because rewriting the stack was too hard.

Pure removed the lie—no SSDs, no fake disks, just software managing raw flash at scale.

The Meta deal isn’t revenue—it’s validation: Pure is becoming the operating system for all-flash data infrastructure.

The Original Sin

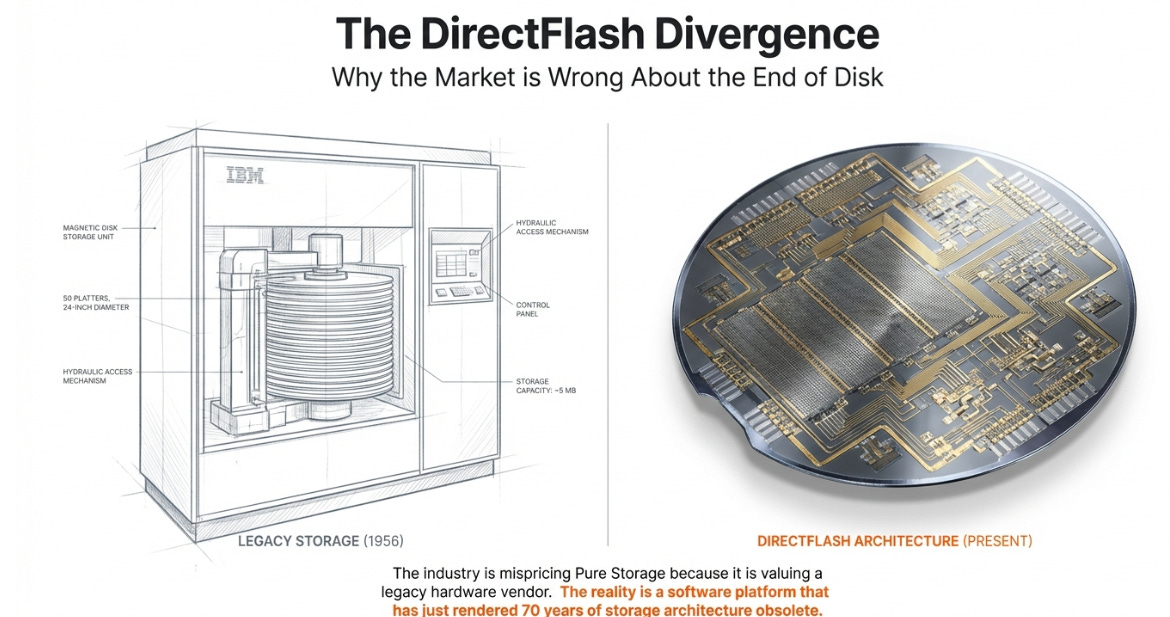

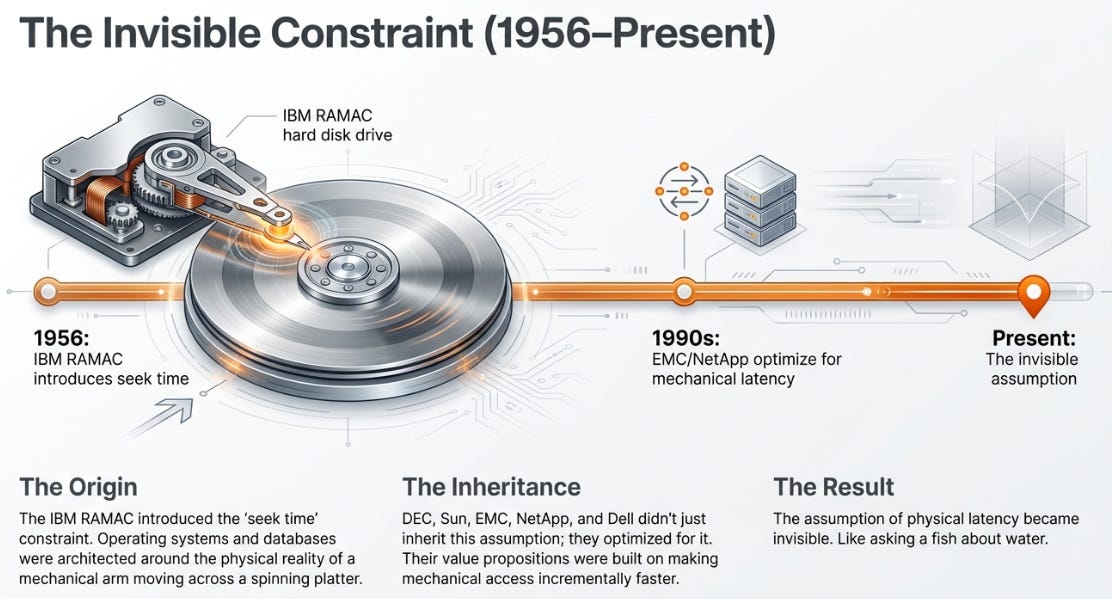

In 1956, IBM engineers in San Jose built a cabinet the size of two refrigerators. Inside: fifty 24-inch aluminum disks coated in magnetic iron oxide, a mechanical arm swinging across the platters to position a read/write head over the exact track containing your data. The 305 RAMAC. The first random-access storage device.

The RAMAC was a miracle. Before it, data lived on sequential tape—if you wanted record #5,000, you had to spool past records #1 through #4,999 first. The RAMAC changed that. Point the arm at the right track, wait for the platter to rotate the right sector under the head, and there was your data. Revolutionary.

It was also a catastrophic architectural choice that would haunt the industry for seven decades. Not because the RAMAC was bad—it was brilliant for its time—but because it worked well enough that every piece of software written afterward assumed its limitations were permanent features of reality.

Think about what the RAMAC required: a mechanical arm that had to physically move, then wait for a spinning platter to rotate the correct sector underneath. This took time. Milliseconds, eventually microseconds, but time nonetheless. And so operating systems were designed around seek times. Databases were architected to minimize head movements. File systems were structured to accommodate the physical reality of mechanical latency.

When Digital Equipment Corporation built minicomputers in the 1960s, they inherited this assumption. When Sun Microsystems pioneered networked storage in the 1980s, they inherited it too. When EMC built its storage empire in the 1990s, when NetApp carved out NAS, when Dell acquired its way to market leadership—they didn’t just inherit the assumption. They optimized for it. Their entire value propositions were built on making disk access incrementally faster, incrementally more reliable.

Nobody questioned whether the assumption was still valid. It had been true for so long that questioning it felt like questioning gravity. The assumption of physical latency became invisible. Like asking a fish about water.

The Flash Fallacy

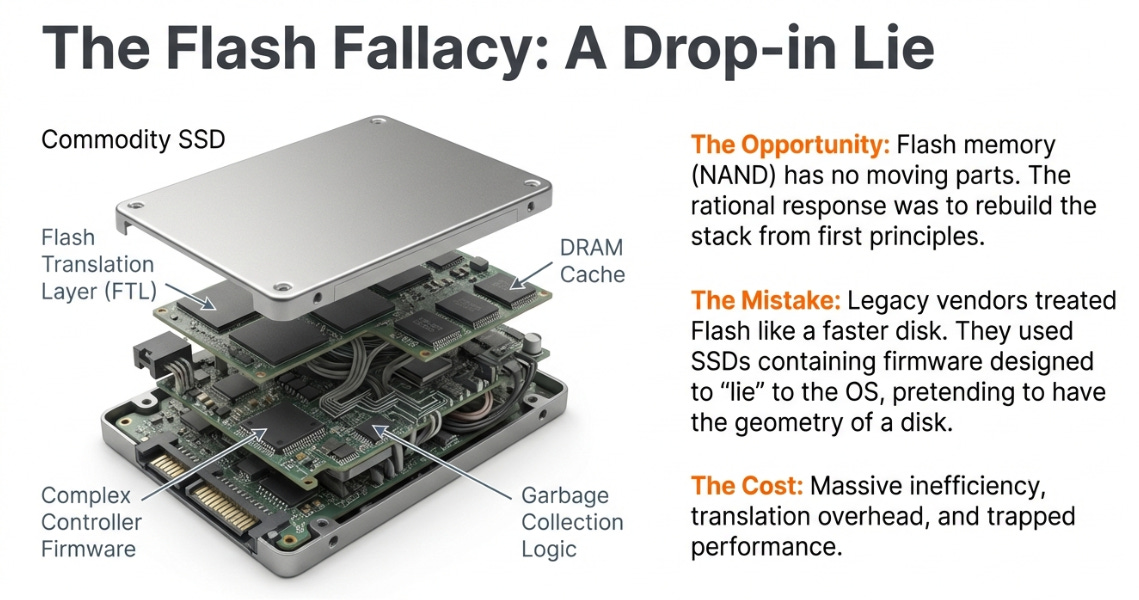

Flash memory should have changed everything. NAND flash has no moving parts. No mechanical arm. No spinning platter. No seek time. No rotational latency. When you ask for data from flash, it’s just there—limited only by the speed of electrons moving through silicon, which is to say, barely limited at all by the standards of the disk era.

The rational response to this technological shift would have been to rethink everything. The file systems. The interfaces. The management software. The entire stack, rebuilt from first principles for a world where the fundamental constraint had evaporated.

That’s not what happened.

Instead, Dell, NetApp, and HPE did something entirely understandable but ultimately self-defeating: they treated flash as a drop-in replacement for spinning disks. They bought Solid State Drives from Samsung, Micron, and Western Digital—drives containing their own controllers, their own DRAM caches, their own firmware designed to make flash look like a disk to systems expecting one.

The SSDs were lying. Pretending to be something they weren’t, translating between what the storage array expected and what the silicon actually did. And the storage vendors paid a premium for the deception—both the dollar premium of embedded controllers and the performance premium of translation overhead.

This wasn’t stupidity. It was path dependence operating exactly as it always operates. Dell had billions invested in PowerStore architectures. NetApp’s ONTAP software assumed certain behaviors. HPE’s customers had built processes around specific capabilities. Ripping out the foundation would have been expensive, risky, and politically treacherous.

More importantly, the drop-in approach worked. Customers got faster storage. Vendors maintained margins. Everyone was happy. The fact that the architecture was compromised didn’t matter in the short term. And in enterprise technology, the short term has a way of extending indefinitely.

Except the economics were wrong. And economics is patient. It can wait decades.

The Cheat Code

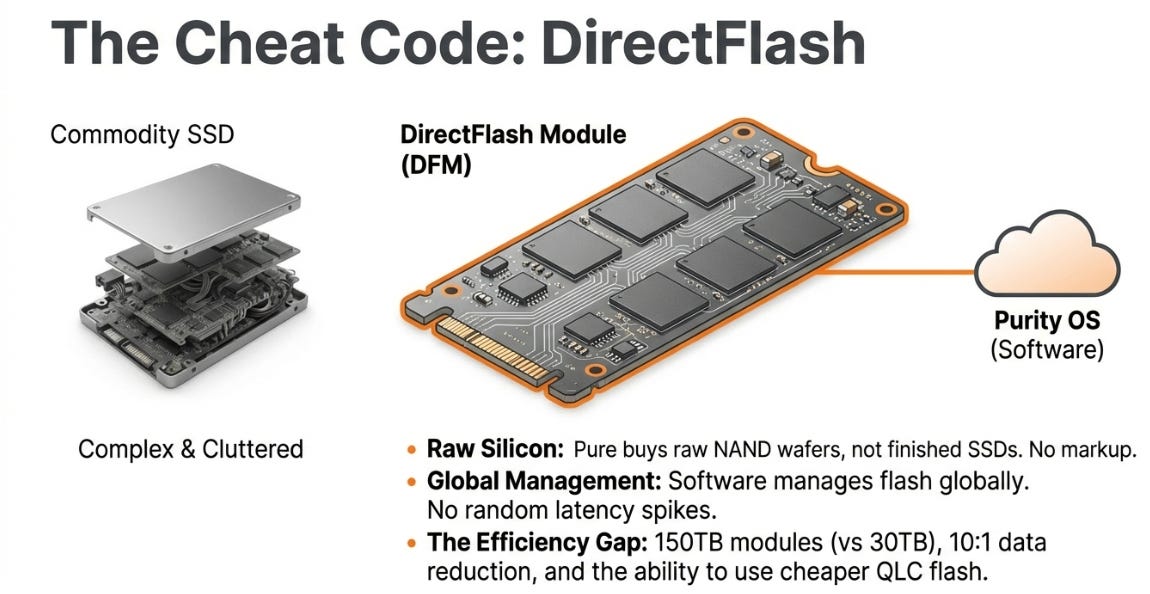

Pure Storage was founded in 2009 with a thesis that sounded almost reckless: what if you built a storage company that refused to buy SSDs at all?

The idea was elegant and brutal. Instead of purchasing finished drives with embedded controllers and markup, Pure would buy raw NAND wafers directly from the fabs. They would build their own modules—DirectFlash—that exposed raw silicon to their software layer. No pretense. No translation. No lies.

Their operating system, Purity, manages flash globally across the entire array rather than letting each drive manage itself in isolation. When you buy commodity SSDs, each drive runs its own garbage collection—the housekeeping that maintains performance. The drives don’t coordinate, which means random performance hiccups as individual drives decide it’s maintenance time. Pure coordinates maintenance across the entire system. Consistent, predictable latency—something enterprises pay substantial premiums for.

By controlling the full stack, Pure could do things commodity SSD buyers couldn’t attempt. Use cheaper QLC flash for workloads competitors insisted required expensive TLC. Ship 150TB modules while competitors struggled with 30TB drives. Achieve 10:1 data reduction while Dell guaranteed 4:1.

Each advantage was meaningful alone. Together, they compounded into something more important: Pure removed an entire layer of markup that competitors can’t eliminate without abandoning their architectures.

Dell can’t just stop buying SSDs. Their software expects SSDs. Their qualification processes take 18 months. Their field reps are compensated on SSD-era margin structures. The switching costs aren’t technical—they’re written into the org chart, the partner agreements, the financial models. Pure found a cheat code no one else can use without burning down their existing business first.

For fifteen years, the market shrugged. Pure was a niche player, growing nicely but not threatening the established order. Then Meta called.

The Watershed

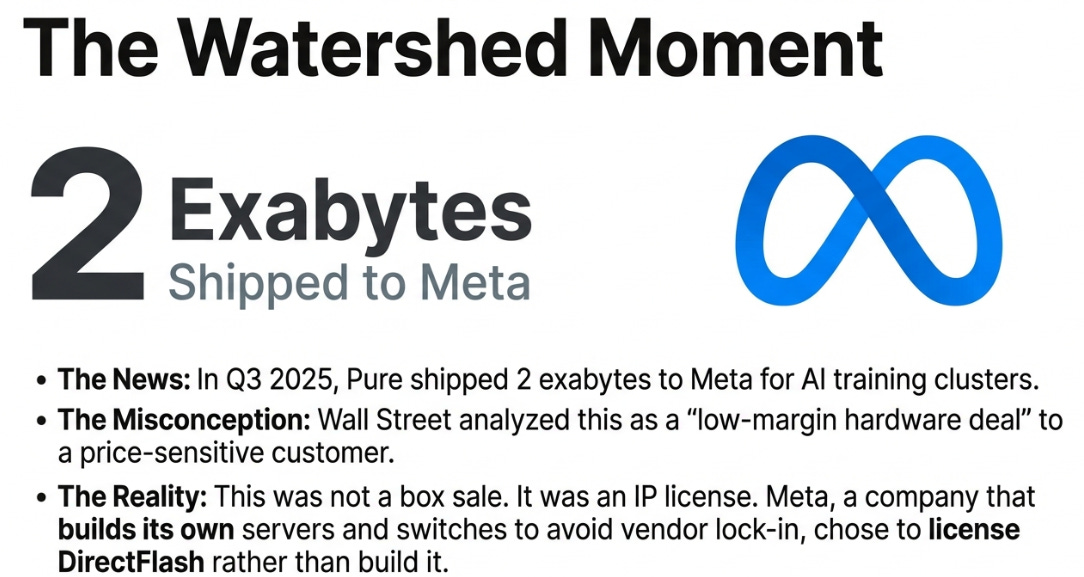

Buried in Pure’s Q3 2025 earnings: 2 exabytes shipped to a single hyperscaler customer.

I heard the name from three sources in two days, each whispering it like a secret they weren’t supposed to share. Meta.

Wall Street’s reaction was telling. Analysts categorized it as a “low-margin hardware deal”—another box sale to a customer notorious for squeezing suppliers. The stock barely moved.

They missed it entirely.

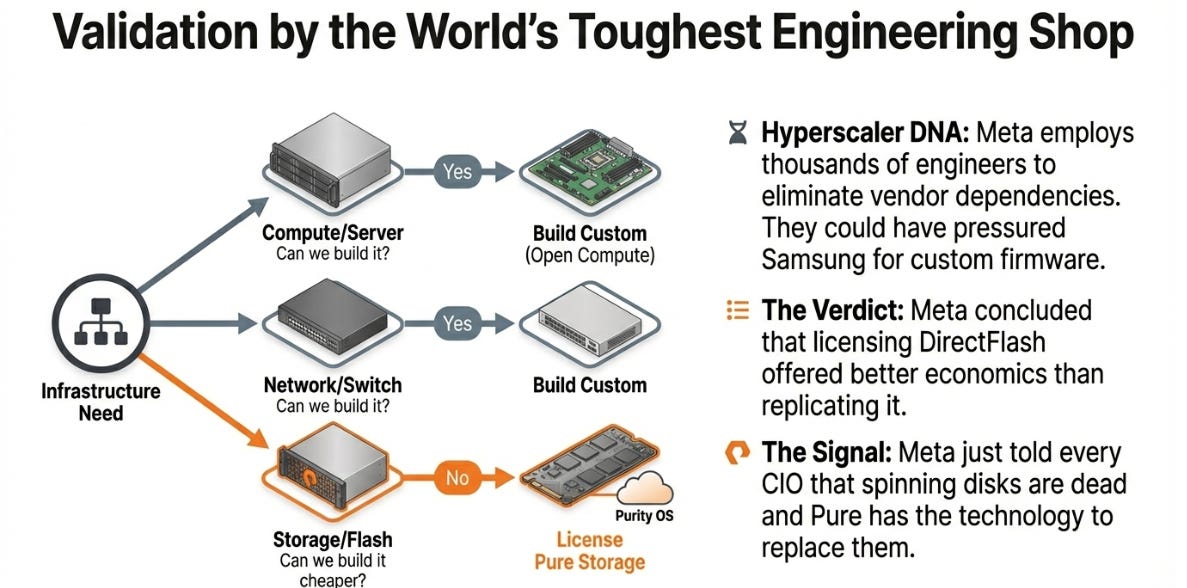

To understand why, you have to understand how hyperscalers think. Companies like Meta don’t buy technology the way enterprises do. They employ thousands of engineers whose entire job is to eliminate vendor dependencies and build custom solutions. When Meta needs servers, they design their own. When they need networking, they build their own switches. When they need storage, they’ve historically done the same.

So when Meta’s infrastructure team—arguably the most sophisticated storage buyers on Earth—evaluated options for AI training clusters, they could have built their own flash management layer. They’ve done exactly that for other components. They could have pressured Samsung for custom firmware. At Meta’s scale, suppliers accommodate unusual requests. They could have used commodity solutions their systems already integrated with.

They chose Pure. They chose to license the IP.

Meta—a company with unlimited engineering resources, unlimited capital, and a cultural predisposition to build rather than buy—concluded that licensing DirectFlash was better economics than replicating it in-house. That’s not a hardware sale. That’s validation of architectural superiority from the most demanding customer imaginable.

Meta just told every CIO in America that spinning disks are dead and Pure has the technology to replace them. Wall Street filed it under “low-margin hardware.”

The Toll Road

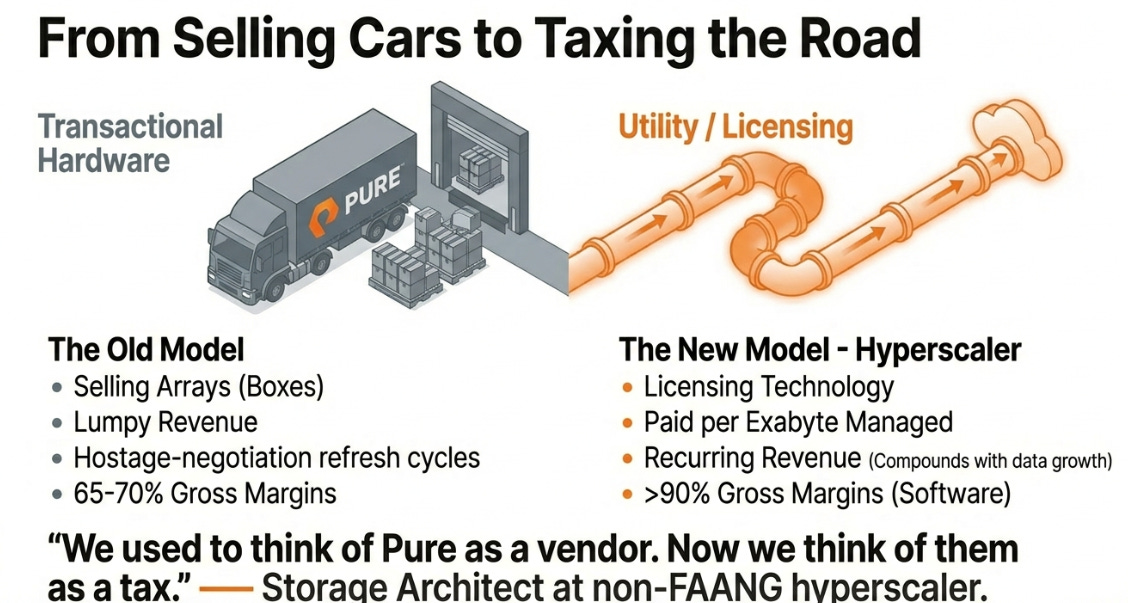

Think about the difference between selling someone a car and getting paid every time they drive.

Dell sells cars. Big storage arrays shipped to data centers. Revenue recognized when the truck pulls away. Then silence until the next refresh cycle, when negotiations feel like hostage situations—because that’s exactly what they are. Lumpy revenue. Competitive pricing. Customers who view you as a necessary evil.

Pure is building a toll road.

The hyperscaler deals aren’t structured like enterprise sales. Pure isn’t shipping racks to Meta’s loading dock the way they ship FlashArrays to Goldman Sachs. They’re licensing technology. Getting paid per exabyte managed by their software, not per box delivered.

The margin profile is completely different. Traditional storage hardware runs 65-70% gross margins if you’re good. Software royalties—licensing IP without associated hardware costs—run above 90%.

The revenue recognition is different too. Enterprise deals are inherently lumpy: big orders when customers refresh, then quiet quarters while they digest. Licensing creates predictable, recurring revenue that compounds as footprints grow. Meta isn’t going to shrink their AI infrastructure. The deal gets bigger automatically. Every year. Without additional sales effort.

A storage architect at a non-FAANG hyperscaler put it to me this way: “We used to think of Pure as a vendor. Now we think of them as a tax.”

He meant it as a compliment. Taxes are unavoidable. Taxes compound. Taxes don’t require quarterly sales calls.

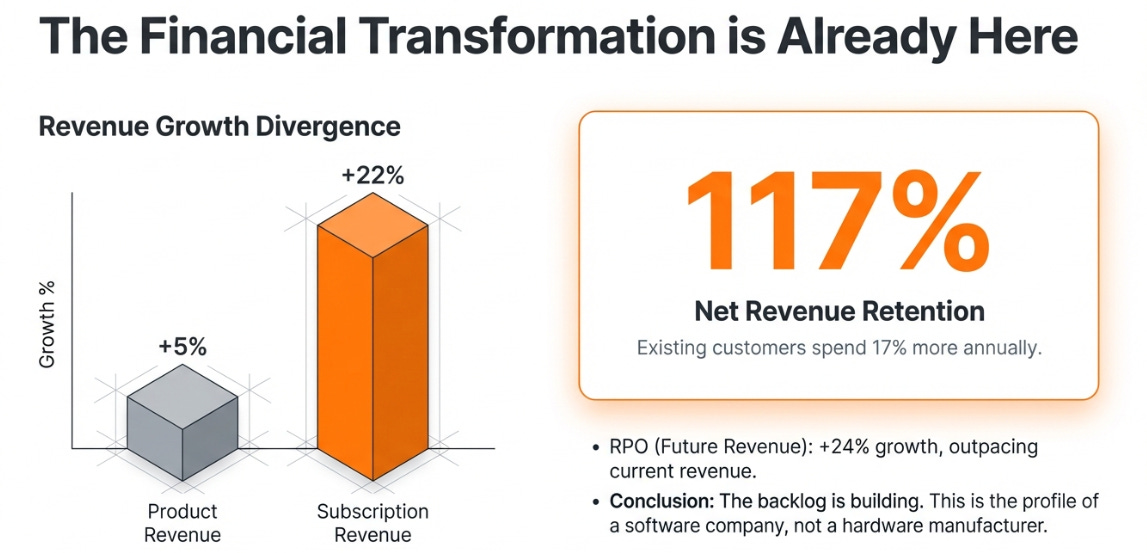

The numbers tell the story. Subscription revenue grew 22% while product revenue grew 5%. Remaining Performance Obligations—contracted future revenue—grew 24%, outpacing current revenue by 8 points. The backlog buffer is building, not depleting.

The market sees Pure as a hardware company with recurring revenue attached. What’s actually happening: Pure is becoming a software licensing company that happens to ship some hardware.

The Endgame

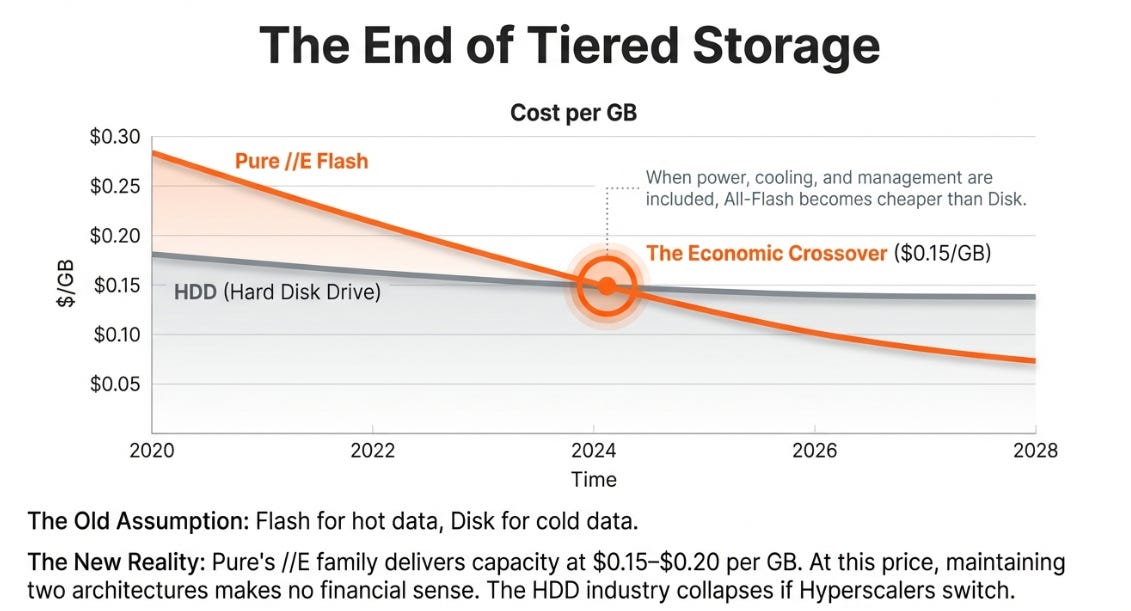

For a decade, enterprise IT operated under an assumption so fundamental that questioning it marked you as naive: spinning disks are cheap, flash is expensive. Hot data on flash. Cold data on disk. “Tiered storage.” Universally accepted. Questioning it made you sound like a Pure salesperson.

That was the point.

Pure’s FlashArray//E now delivers capacity at $0.15-0.20 per gigabyte—approaching enterprise disk economics when you factor in density, power, cooling, and management overhead. Their roadmap targets sub-$0.10. At that price, tiered storage stops making economic sense. Why maintain two architectures when one handles everything?

Hyperscalers buy 60-70% of the world’s hard disk drives. If Meta’s bet proves out—if the all-flash data center becomes default for AI training, inference, and cold storage—the ripple effects are enormous. Seagate and Western Digital lose their biggest customers. Dell and NetApp lose differentiation. The industry restructures around a new assumption: flash, with no fallback.

Pure wouldn’t just be a storage vendor. They’d be the operating system for enterprise data infrastructure. The toll road everyone takes to reach flash.

The Risks (And Why They Matter Less Than You Think)

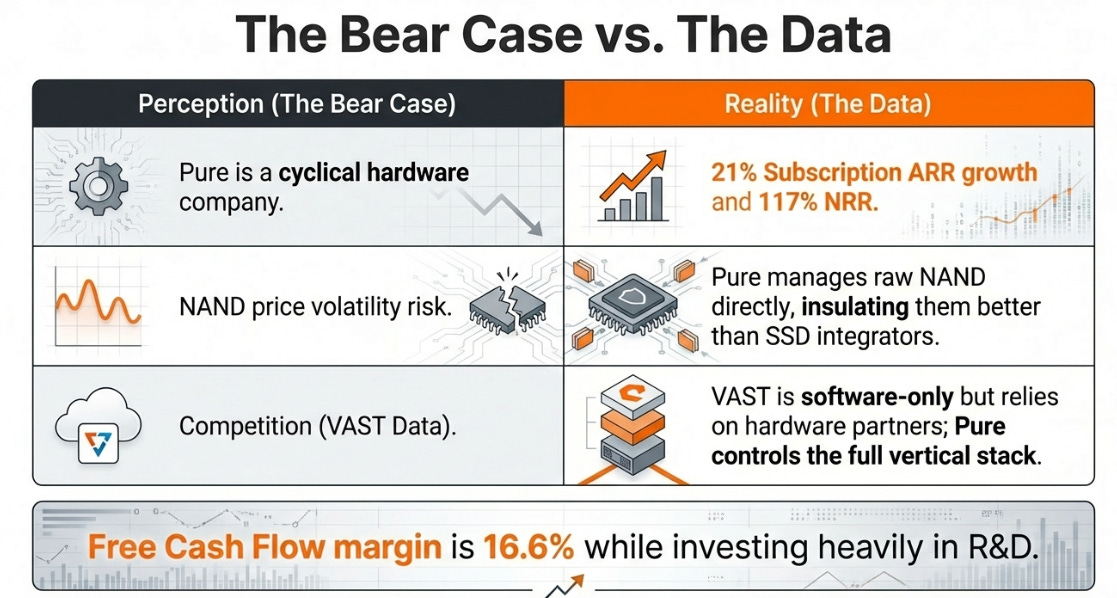

The obvious risks are real. NAND prices are volatile—TrendForce forecasts 30-40% increases through 2026. Competition from AI-native startups like VAST Data is intensifying. Dell isn’t going to cede the market quietly.

And there’s execution risk on hyperscaler deals. Management stopped providing detailed shipment data—which could mean “numbers are so good we’re hiding momentum” or “numbers aren’t developing as expected.” Opacity cuts both ways.

But here’s what bears miss: Pure has already escaped the hardware trap.

Subscription ARR hit $1.7 billion, growing 21% annually. Net revenue retention sits at 117%—existing customers spend 17% more each year before new acquisition. Free cash flow reached $526 million on $3.17 billion revenue—16.6% margins while investing heavily in R&D.

These aren’t hardware metrics. Hardware companies don’t post 21% recurring revenue growth. Hardware companies don’t achieve 117% retention.

The bears are analyzing Pure as a hardware company facing cyclical pressure. They’re looking at the wrong business.

The Trade

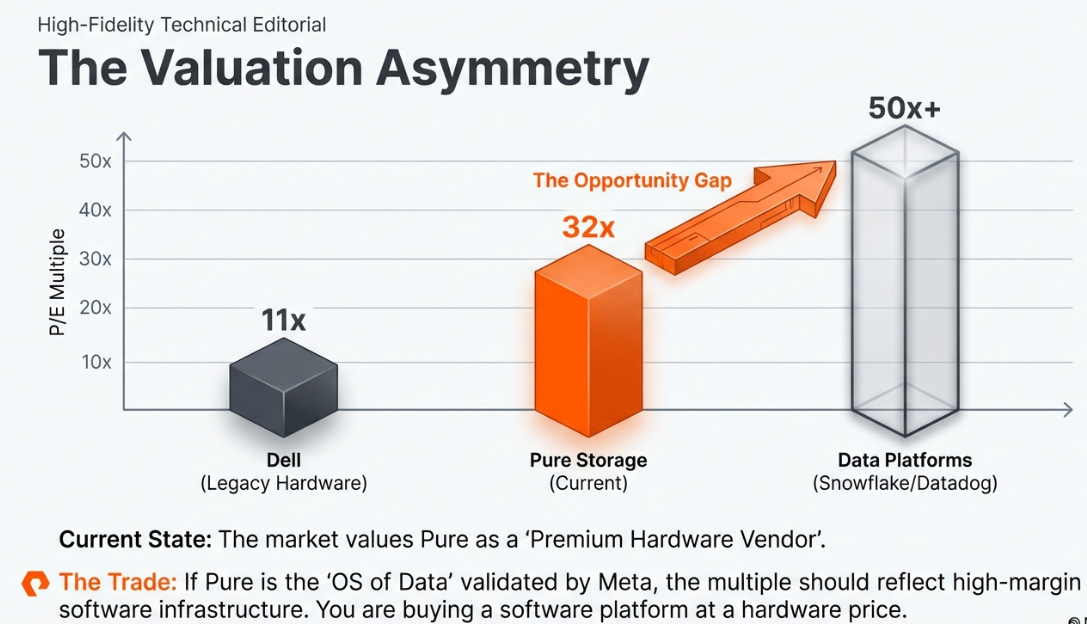

Pure trades at 32x forward earnings. Dell trades at 11x. The market sees something different—but the multiple still assumes Pure is primarily a hardware company that happens to execute better. Best house in a bad neighborhood.

Pure isn’t in the neighborhood.

If Meta scales. If more hyperscalers sign. If the //E family kills the disk market. Then Pure isn’t valued on hardware comps. It’s valued on infrastructure comps. On the multiple you’d pay for the operating system of the world’s data.

At 32x, you’re betting they’re a better storage vendor. At 50x, you’re betting they’re building infrastructure. The distance isn’t incremental. It’s categorical.

You can buy a company transitioning from hardware to licensing, from enterprise to hyperscaler, from vendor to platform—at a multiple that assumes most of that transition fails.

The real sin of the RAMAC wasn’t the mechanical arm. It was that we spent seventy years optimizing for a constraint Pure decided to ignore.

Meta didn’t validate Pure’s thesis. They revealed that everyone else had been solving the wrong problem.

The disk is already dead.

The market hasn’t noticed yet.

That’s the trade.

Disclaimer:

The content does not constitute any kind of investment or financial advice. Kindly reach out to your advisor for any investment-related advice. Please refer to the tab “Legal | Disclaimer” to read the complete disclaimer.