Rheinmetall AG - Steel After Silence

How Europe's Most Boring Company Became Its Explosive Investment

TLDR

From Boring to Battlefield Backbone: Rheinmetall, long dismissed as a sleepy industrial supplier, has transformed into Europe’s most strategically critical defense platform—leveraging two decades of optionality to dominate a €200B+ rearmament wave triggered by the Ukraine war.

Platform, Not Products: The company’s shift from cyclical hardware sales to high-margin, software-enabled defense ecosystems (e.g., Lynx IFV, digital battlefield services) positions it for recurring revenue and justifies its premium technology-like valuation.

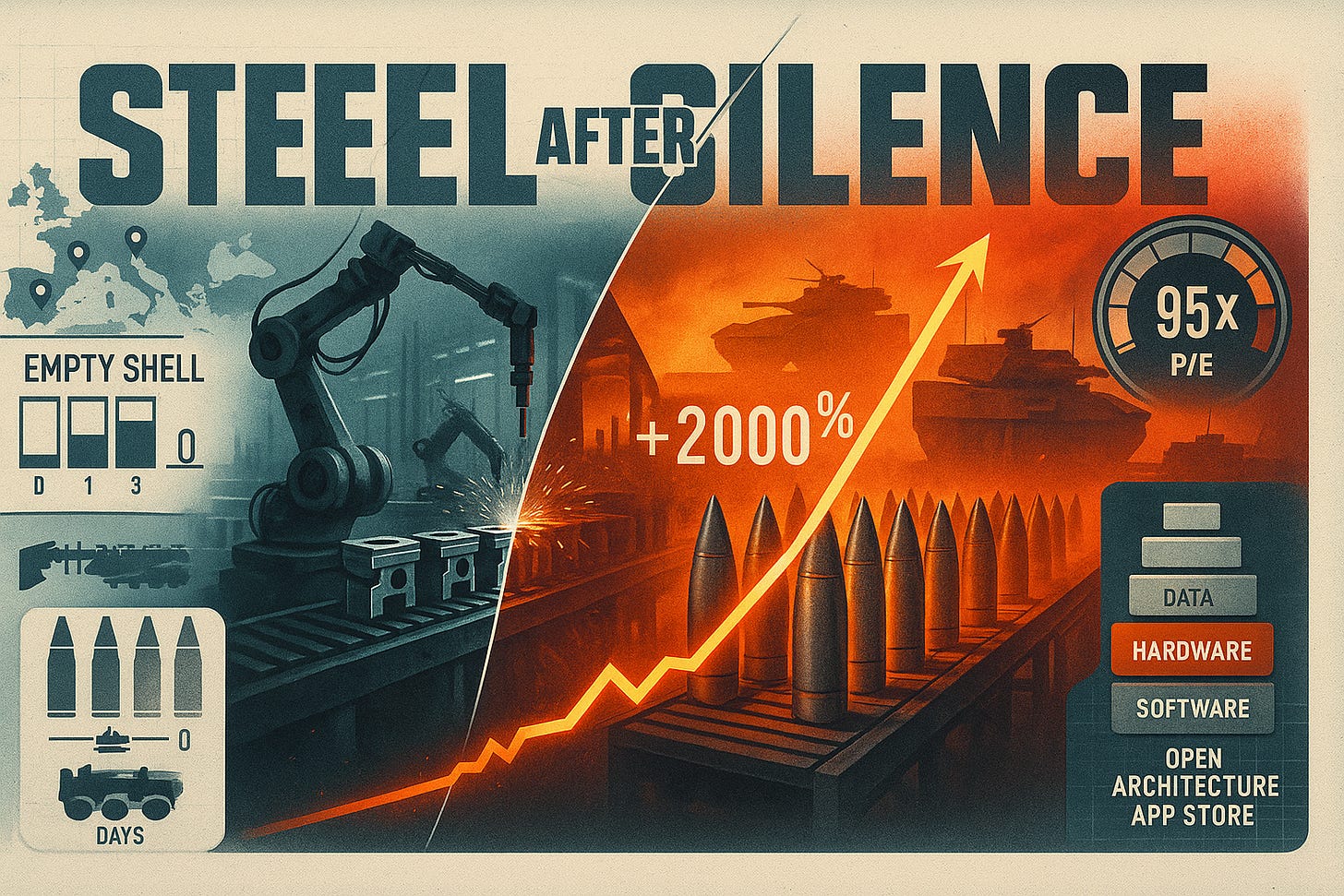

Valuation at a Knife’s Edge: With 54x NTM P/E multiple and +2,000% stock gain, the current price reflects near-perfect execution. Structural policy moats and revenue backlog support the bull case, but geopolitical de-escalation or platform delays could trigger sharp downside.

"The Empty Shell Crisis"

March 2022. Eastern Ukraine. The artillery officer's radio crackled with another fire mission as Russian armor pushed toward Kramatorsk. He reached for the ammunition rack—and found it empty. Not just low. Empty.

For the third time that week.

Across the front lines, NATO-standard 155mm shells were disappearing faster than anyone had imagined possible. Ukraine was burning through a month's worth of Western ammunition stocks every 48 hours. Artillery batteries fell silent not from enemy fire, but from empty magazines.

Six hundred miles west, in a glass tower overlooking the Rhine, Armin Papperger's phone wouldn't stop ringing. Defense ministers who hadn't called Rheinmetall in years were suddenly desperate. How fast could production scale? What were the bottlenecks? Could ancient ammunition lines be reactivated?

The man who had spent two decades defending Rheinmetall's "boring" dual identity—half automotive pistons, half niche defense—suddenly found himself at the center of Europe's most urgent industrial mobilization since World War II.

This is the story of how a century-old metal-bender became Europe's new security linchpin, and why its €82 billion valuation might be either the most prescient investment of the decade or its most spectacular bubble.

Legacy & Lethargy

Rheinmetall AG didn't start life as a carburetor company. Founded in 1889 as Rheinische Metallwaren- und Maschinenfabrik, it was pure weapons from day one—rapid-fire field guns for Kaiser Wilhelm's army, ammunition for two world wars, tanks for the Wehrmacht.

But defeat has a way of redirecting corporate destiny. Post-1945 Germany needed rebuilding, not rearming. The Allies dismantled weapons factories and banned military production. Rheinmetall's engineers, suddenly prohibited from making things that exploded, turned their metallurgy skills toward things that moved: pistons, engine blocks, fuel injection systems.

For five decades, this worked brilliantly. Germany's automotive miracle needed precisely what Rheinmetall could provide—high-precision metal components for BMW, Mercedes, and Volkswagen. Defense became an afterthought, a small division kept alive more from institutional memory than strategic conviction.

The Cold War's end in 1991 seemed to vindicate this pivot. The "peace dividend" was real money—defense budgets across Europe plummeted from 3-4% of GDP to barely 1%. Politicians competed to slash military spending fastest. Who needed tanks when the main threat was keeping the Deutsche Mark stable?

Rheinmetall embodied this comfortable complacency. By 2020, automotive components generated 70% of revenue. Defense was the awkward stepchild—profitable enough to justify keeping around, too small to drive strategy. Investors punished this strategic ambiguity with a conglomerate discount. Pure-play suppliers commanded premium valuations; Rheinmetall traded like a confused industrial.

But in those Düsseldorf boardrooms, a few voices kept asking uncomfortable questions. What if the peace didn't last? What if Europe needed weapons again? What if maintaining dual capabilities—expensive as it was—might prove prescient someday?

Kosovo in 1999. Georgia in 2008. Crimea in 2014. Each crisis generated nervous inquiries from NATO capitals, small orders for trucks and ammunition, just enough to keep the lights on in mothballed facilities. But the fundamental assumption held: large-scale warfare in Europe was finished. The future belonged to precision strikes and cyber warfare, not mass-produced artillery shells.

Rheinmetall's defense engineers watched their automotive colleagues receive bigger budgets and clearer mandates. Every euro spent maintaining ammunition production knowledge was a euro that couldn't go toward electric vehicle components. The optionality wasn't free.

Yet they persisted, treating defense as expensive insurance against an uncertain future. For 23 years, that premium kept coming due with no apparent payout.

Until February 24, 2022.

The "Zeitenwende" Big Bang

At 5 AM Moscow time, Russian armored columns crossed into Ukraine from three directions. By noon, it was clear this wasn't another limited "special operation"—this was Europe's largest military conflict since 1945.

The implications hit Western military planners within days. NATO's ammunition cupboards, optimized for small-scale expeditionary warfare, contained perhaps 300,000 artillery shells total. Ukraine was firing that many in a month. If this war lasted years—as wars usually do—the West would quite literally run out of bullets.

The phone calls to Düsseldorf started Friday. By Saturday, Papperger was fielding desperate inquiries from defense ministers across the alliance. How quickly could production ramp? What were the chokepoints? Which facilities could be reactivated?

Then came Sunday, February 27—just 72 hours after the invasion began. Chancellor Olaf Scholz stood before Germany's Bundestag and announced a €100 billion special fund for military modernization, instantly doubling the country's defense budget. He called it "Zeitenwende"—turning point.

European defense spending, which had declined for three decades, reversed overnight. Poland committed to 4% of GDP on defense. The Baltic states pushed toward 3%. Even pacifist Germany pledged to meet NATO's 2% minimum for the first time since the Cold War.

For Rheinmetall, this represented vindication on an almost biblical scale. The expensive insurance policy maintained through decades of investor skepticism suddenly looked prophetic. While competitors scrambled to understand how to manufacture ammunition at scale, Rheinmetall already knew. The knowledge that seemed like costly nostalgia on February 23 became priceless on February 28.

The transformation was immediate and mathematical. Orders that would have taken years to negotiate were signed in weeks. The German government awarded Rheinmetall framework contracts worth €7+ billion for artillery ammunition. Allied nations began reaching out about everything from tank upgrades to air defense systems.

Rheinmetall's stock price, which had languished around €87 in early 2022, began a relentless climb. €200 by summer. €400 by year-end. €800 by mid-2023. €1,803 by July 2025—a 2,000% gain that turned a sleepy industrial into one of Europe's most valuable companies.

But behind the numbers lay something more profound: the realization that Rheinmetall's 23-year bet on maintaining defense capabilities—dismissed as strategic confusion by generations of analysts—had been the most prescient corporate decision of the 21st century.

Capacity as Destiny

What followed was perhaps the most rapid industrial transformation in peacetime European history. Rheinmetall didn't just scale existing operations—it fundamentally reimagined what it meant to be a defense manufacturer in the modern world.

The ammunition business revealed why capacity matters more than patents when people are shooting at each other. Making artillery shells isn't like assembling smartphones. It requires mastering chemistry (nitrocellulose propellants), metallurgy (forged steel cases), precision machining (rifling that determines accuracy), and energetics (explosive fillings that can't be outsourced to the lowest bidder).

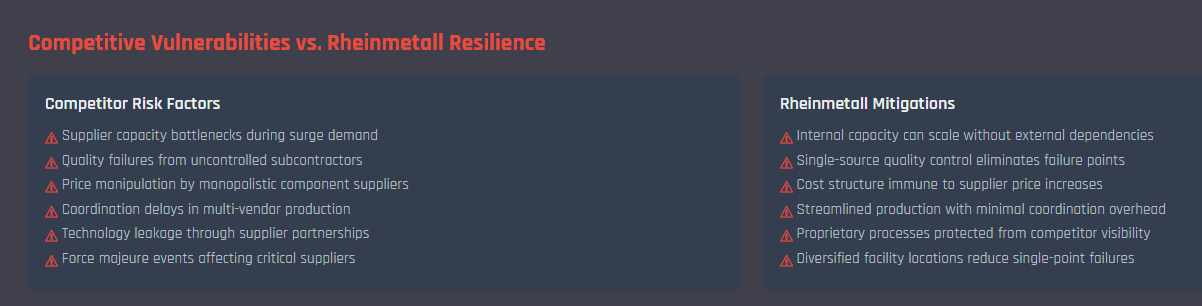

Rheinmetall possessed something competitors couldn't replicate: complete vertical integration. While rivals relied on subcontractors for propellants or precision components, Rheinmetall controlled the entire supply chain. Its Unterlüß facility could produce nitrocellulose, cast propellant grains, machine steel cases, and assemble finished rounds in a single complex.

This mattered because ammunition manufacturing has no margin for error. A single quality failure doesn't just mean lost revenue—it can mean criminal liability if defective rounds kill friendly forces. Customers will pay premium prices for suppliers they trust with their soldiers' lives.

The €8 billion capital expenditure blitz that followed targeted this chokepoint advantage. New ammunition plants in Germany and Lithuania. Expanded propellant production. Additional barrel-forging capacity. Joint venture discussions for facilities in Ukraine itself, turning customer into production partner.

But Rheinmetall's leadership understood something Wall Street missed: the future of defense wasn't just bigger factories making more of the same products. It was the convergence of traditional hardware with digital technology, creating platforms rather than products.

Consider the Lynx infantry fighting vehicle. On paper, it's a traditional armored troop carrier—steel, tracks, cannon. In reality, it's a mobile computer system that happens to have armor plating. Its open digital architecture allows plug-and-play integration of sensors, weapons, communications gear, and defensive systems. Software updates can change capabilities without touching hardware.

This matters because modern militaries buy systems, not equipment. A tank battalion doesn't just need vehicles—it needs training simulators, maintenance programs, ammunition resupply, software upgrades, and technical support. Once customers standardize on Rheinmetall's digital backbone, switching to competitors becomes prohibitively expensive.

The numbers validate this platform approach. Rheinmetall's order backlog exploded from €30 billion in 2021 to €62 billion by 2025—representing nearly six years of guaranteed revenue. More importantly, 75% of these contracts include inflation escalation clauses, protecting margins against rising costs.

Yet even as production lines hummed at maximum capacity, Rheinmetall's engineers were already thinking beyond the current crisis. Because the most successful defense companies aren't those that fight the last war—they're those that prepare for the next

From Hardware to Defence-Tech Platform

The missiles started falling on Ukraine in patterns no one had seen before. Swarms of Iranian drones followed by precision strikes. Electronic warfare jamming communications. Cyber attacks disabling power grids. The war wasn't just about tanks and artillery—it was about software, satellites, and artificial intelligence.

Rheinmetall's response revealed the company's true strategic evolution. In April 2025, it announced a joint venture with Lockheed Martin to produce rocket motors for European missile systems. Two months later, a partnership with ICEYE brought satellite surveillance capabilities to its platform. By summer, deals with Anduril Industries added autonomous systems to the portfolio.

These weren't random acquisitions—they were calculated moves to transform Rheinmetall from a manufacturing company into what Silicon Valley would recognize as a defense technology platform.

The financial implications are staggering. Traditional ammunition manufacturing operates on 8-12% margins—decent for industrial products, but nothing special. Software and digital services command 40%+ margins. A single software license that costs €50,000 to develop can be sold thousands of times with minimal marginal cost.

Rheinmetall's digital strategy centers on what it calls "open architecture"—standardized interfaces that allow third-party developers to create applications for its platforms. Think of it as the iOS App Store for military equipment. Every Lynx vehicle becomes a node in a larger network, generating recurring revenue through software updates, sensor upgrades, and data analytics services.

The market hasn't fully grasped this transformation. Sell-side analysts still model Rheinmetall as a cyclical industrial, applying traditional manufacturing multiples to what's becoming a technology platform. If digital services reach 10% of revenue by 2028—a conservative target given current trajectory—the entire valuation framework changes.

Consider the Lockheed Martin partnership more closely. Europe faces a critical shortage of solid rocket motor production, having relied on U.S. suppliers for decades. Rheinmetall's expertise in energetics and propellants positions it to become Europe's primary missile propulsion supplier. Given that a single missile can cost €500,000-2 million, and Europe needs thousands to rebuild deterrent capability, this represents billions in high-margin revenue.

The ICEYE space surveillance partnership opens an even larger opportunity. Modern warfare requires real-time intelligence about enemy movements, and satellite data has become as critical as ammunition. By integrating space-based reconnaissance with ground systems, Rheinmetall creates an ecosystem where customers can't easily switch suppliers without losing operational capabilities.

But perhaps the most overlooked aspect is the recurring nature of this business. Unlike traditional defense contracts that end when equipment is delivered, platform-based businesses generate revenue for decades through upgrades, maintenance, and expanded capabilities. A Lynx vehicle sold today could generate software licensing fees for its entire 20-year service life.

This shift from products to platforms explains why Rheinmetall trades at technology company multiples despite being a century-old manufacturer. Investors aren't just buying current capacity—they're buying a position in Europe's emerging defense technology ecosystem.

The Valuation Knife-Edge

By July 2025, something unprecedented was happening in global equity markets: a manufacturer of tanks and artillery shells was trading at 54x NTM PE—a multiple typically reserved for hypergrowth software companies.

Rheinmetall's €82.5 billion market capitalization had swollen beyond established defense giants like BAE Systems or Lockheed Martin. Its enterprise value exceeded that of major technology companies. On any traditional metric—price-to-sales, price-to-book, enterprise value to EBITDA—the stock appeared spectacularly overvalued.

Yet sophisticated investors kept buying, driving the share price from €87 in early 2022 to €1,803 by mid-2025. The mathematics were startling: even assuming flawless execution of expansion plans, margins sustainably above 15%, and revenue growth of 25%+ annually through 2028, the stock required extraordinary performance just to justify current levels.

Bull Case (€3,000): Everything Goes Right The optimistic scenario assumes NATO defense spending reaches 3.5% of GDP, Rheinmetall captures 20-25% market share, digital services scale to 15% of revenue at 40%+ margins, and the company achieves €28 billion in sales by 2028. Under these assumptions—and applying a 40x P/E multiple to reflect platform economics—the stock could reach €3,000.

Probability: 30%. This requires perfect execution across dozens of complex projects, sustained political support for massive defense budgets, successful technology integration, and no significant competitive threats for half a decade.

Base Case (€1,650): Reality Meets Expectations The realistic scenario assumes more modest NATO spending at 2.8% of GDP, normal execution challenges, margin compression as competition rebuilds capacity, and revenue reaching €22 billion by 2028. Applying a 30x P/E multiple yields a target price around €1,650.

Probability: 50%. This scenario acknowledges that while Rheinmetall is well-positioned, extraordinary growth eventually moderates and margins normalize toward industry averages.

Bear Case (€520): The Cycle Turns The pessimistic scenario assumes geopolitical tensions ease, European fiscal pressures force defense budget cuts, execution failures emerge in capacity expansion, and margins compress to historical averages around 8%. Revenue peaks at €15 billion before declining, warranting a 20x P/E multiple.

Probability: 20%. This reflects the reality that defense spending is inherently cyclical, and current levels represent political responses to crisis rather than sustainable peacetime baselines.

The probability-weighted expected value suggests a fair price around €1,859—remarkably close to current trading levels. This implies the market has efficiently priced in most scenarios, leaving little margin of safety for unexpected developments.

What makes this valuation particularly precarious is its sensitivity to execution risk. Unlike software companies that can scale with minimal capital, Rheinmetall's growth requires massive physical investments that can't be easily reversed. The €8 billion capacity expansion represents a bet that current demand levels will persist for years—a assumption that history suggests is optimistic.

Moreover, the company faces the classic innovator's dilemma: success in building massive capacity could create future oversupply that destroys the very margin premiums that justify today's valuation. If Rheinmetall and competitors successfully rebuild European ammunition production, the resulting capacity glut could trigger a race to the bottom on pricing.

Yet for all these risks, the company possesses something increasingly rare in modern markets: genuine scarcity value. No one else can manufacture artillery shells at the scale Europe needs. No other company controls complete vertical integration from propellants to finished ammunition. No competitor offers the same breadth of land systems capabilities.

This scarcity commands a premium—the question is whether that premium should be 30x earnings or 54x earnings.

Policy Moats the Market Forgot

While investors obsessed over production capacity and earnings multiples, a quieter revolution was reshaping European defense procurement. The European Union, traumatized by dependence on American weapons and Asian supply chains, was constructing what amounted to industrial tariff walls around its defense sector.

The European Defence Industrial Programme, scheduled for final vote in Q4 2025, would mandate that 40% of all EU defense procurement come from European suppliers. More critically, it would require that sensitive technologies—ammunition, propellants, electronic warfare systems—be manufactured within EU borders.

For Rheinmetall, this represents a structural moat that competitors can't easily breach. American defense giants like Lockheed Martin or Raytheon would find themselves locked out of European competitions unless they established local production. Asian manufacturers face even higher barriers. The regulations effectively create a captive market for European defense champions.

The financial implications are profound but largely unmodeled by Wall Street analysts. If European defense spending reaches €200+ billion annually—a conservative estimate given current trajectories—and Rheinmetall captures even 15% market share within its core competencies, that implies €30+ billion in annual revenue potential.

More importantly, this isn't just about market share—it's about pricing power. When customers have limited supplier options due to regulatory constraints, margins expand. Rheinmetall's ammunition division already demonstrates this dynamic, achieving 19.4% operating margins during the current capacity shortage.

The regulatory framework also advantages companies with existing European manufacturing footprint. While competitors would need years to establish compliant production facilities, Rheinmetall already operates plants in Germany, Spain, Italy, and soon Lithuania. Each facility becomes more valuable as geographic requirements tighten.

Yet this policy moat creates its own risks. European elections in 2026-2027 could bring leadership changes that prioritize fiscal austerity over strategic autonomy. The same political pressures that created massive defense spending increases could reverse them if public attention shifts to domestic priorities.

Germany's upcoming federal elections represent the first major test. If opposition parties successfully argue that defense spending crowds out social programs, the entire European rearmament project could stall. Rheinmetall's valuation assumes sustained political support for elevated military budgets—an assumption that may prove optimistic as economic pressures mount.

Second-Order Shockwaves

The Rheinmetall transformation sent ripples far beyond defense markets. Suppliers of nitrocellulose, forged steel blanks, and precision machining suddenly found themselves in sellers' markets. Chemical companies that had almost abandoned energetics production scrambled to restart mothballed facilities.

The competitive response was equally dramatic. KNDS, the Franco-German consortium combining Krauss-Maffei Wegmann and Nexter, announced €3 billion in capacity investments. Hanwha Defense of South Korea began exploring European production facilities. Even BAE Systems, traditionally focused on aerospace and naval systems, started examining land-based opportunities.

But the most significant shift was philosophical: defense was being rebranded from necessary evil to strategic imperative. ESG investment frameworks, which had systematically excluded weapons manufacturers, began creating carve-outs for "defensive" capabilities. European pension funds, previously prohibited from defense investments, received regulatory permission to support domestic security industries.

This capital flow redirection matters more than most realize. If institutional investors with €30+ trillion in assets under management begin allocating even 1% to European defense stocks, that represents €300+ billion in potential investment. Given the sector's relatively small size, this influx could sustain premium valuations for years.

The supply chain implications extend beyond obvious components. Modern weapons systems require rare earth minerals, advanced semiconductors, and precision optical systems—many currently sourced from China. European attempts to build domestic supply chains for these inputs could create investment opportunities across multiple industries.

AI and autonomous systems represent another layer of complexity. Rheinmetall's partnership with Anduril Industries signals recognition that future warfare will be software-defined. Companies that can integrate artificial intelligence with kinetic systems will command premium valuations. Those that remain purely mechanical risk obsolescence.

Yet this technological evolution also creates disruption risk. If warfare shifts toward cyber attacks, space-based systems, or directed energy weapons, traditional platforms like tanks and artillery could become as obsolete as cavalry charges. Rheinmetall's massive investments in conventional weapons could prove mistimed if military doctrine evolves faster than expected.

"From Pistons to Panther"

In the end, Rheinmetall's story completes a circle that began in a 1950s boardroom when executives made a fateful decision: keep the defense division alive, even if it meant decades of investor criticism and strategic complexity.

That choice—to maintain expensive insurance against an uncertain future—represents one of the most prescient corporate decisions in modern business history. The engineers who preserved ammunition production knowledge through 30 years of peace dividend policies couldn't have imagined their vindication would come through Russian tanks rolling across Ukrainian fields.

But vindication creates its own challenges. Success in crisis doesn't guarantee success in stability. The same geopolitical tensions that created Rheinmetall's opportunity also represent its greatest risk: what happens when those tensions eventually ease?

The company's evolution from industrial manufacturer to defense technology platform offers a potential answer. If Rheinmetall successfully transitions from selling products to operating platforms, from manufacturing hardware to providing software services, it could transcend traditional defense cyclicality.

Yet that transformation remains incomplete and unproven. For all the talk of digital backbones and software platforms, Rheinmetall still generates most revenue from steel and explosives. The platform economics that justify technology company valuations exist more in investor presentations than financial statements.

Perhaps the most profound lesson isn't about Rheinmetall specifically, but about the nature of optionality itself. In a world of quarterly earnings pressure and activist investors demanding focus, maintaining capabilities that might never be needed requires institutional courage. Most companies optimize for efficiency over resilience, cost minimization over strategic flexibility.

Rheinmetall's leaders made the opposite choice, paying the optionality tax for decades while waiting for conditions that might never materialize. When those conditions finally arrived, the payoff was extraordinary—not just financially, but strategically. Europe's security now depends partly on decisions made in Düsseldorf conference rooms decades ago.

For investors, this creates an uncomfortable paradox. The best insurance policies are the ones you hope never to collect on. Rheinmetall's current success stems from European security failure—the breakdown of diplomatic solutions, the return of territorial warfare, the collapse of post-Cold War assumptions about perpetual peace.

As tanks roll through Ukrainian wheat fields and artillery thunders across European battlefields for the first time in 80 years, Rheinmetall stands as both beneficiary and symbol of humanity's failure to transcend its violent history.

The €82 billion question facing investors today is whether this failure is temporary or permanent, whether Rheinmetall's renaissance represents a cyclical opportunity or a structural transformation.

The answer will determine whether today's shareholders join the ranks of the prescient contrarians who bet against peace—or become tomorrow's cautionary tale about the dangers of paying technology prices for industrial businesses.

In either case, the company that learned to forge both pistons and Panther tanks has already secured its place in the annals of corporate reinvention. Whether that reinvention justifies its current valuation remains the most expensive question in European markets.

Disclaimer:

The content does not constitute any kind of investment or financial advice. Kindly reach out to your advisor for any investment-related advice. Please refer to the tab “Legal | Disclaimer” to read the complete disclaimer.