Rolls Royce: The Physics of Pricing Power

How Rolls-Royce transformed from distressed manufacturer into monopoly rent-collector, and why the market still misreads the story

TL;DR:

Rolls-Royce spent a decade buying exclusivity and building an installed base — then nearly died before the payoff arrived.

The turnaround wasn’t cost-cutting; it was monetizing switching costs (TotalCare + A350/A330neo exclusivity = toll booth economics).

The stock now prices perfection: the real edge isn’t the thesis — it’s waiting for the right entry point.

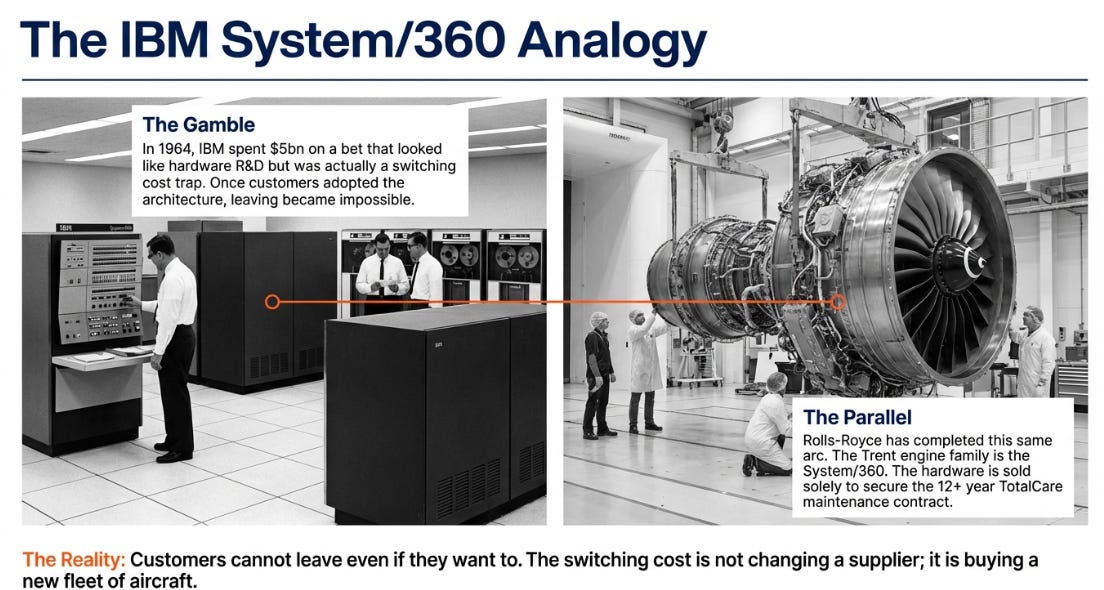

In 1964, IBM spent more money than the Manhattan Project on something Wall Street thought was insane. The System/360 would unify IBM’s fragmented product lines into a single architecture, a $5 billion bet that threatened to cannibalize existing profits for uncertain future gains.

Wall Street was right to be skeptical, but for the wrong reason. IBM wasn’t gambling on hardware. They were building a trap.

Once customers adopted System/360, leaving meant rewriting every piece of software, retraining every employee, re-architecting every workflow. The switching costs compounded invisibly until they became insurmountable. What looked like reckless R&D spending revealed itself as a thirty-year annuity, high-margin maintenance and upgrade revenue from customers who couldn’t leave even if they wanted to.

This pattern repeats across industries, though rarely so visibly. A company makes enormous upfront investments that look like value destruction, only to reveal themselves as toll booths once customers are locked in.

Rolls-Royce Holdings just completed this arc. And the market still doesn’t fully understand what happened.

The Unpriced Monopoly

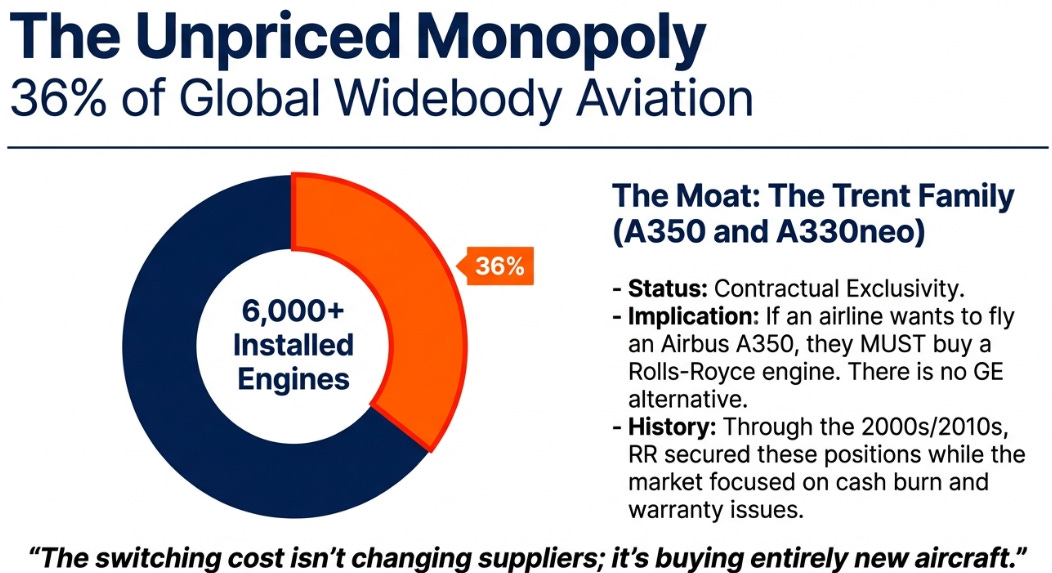

The Trent engine family was Rolls-Royce’s System/360. Through the 2000s and 2010s, the company spent billions securing contractual exclusivity on Airbus’s widebody aircraft, the A350 and A330neo. If you want to fly those planes, you buy Rolls-Royce engines. There is no alternative. Not because competitors couldn’t build one, but because Rolls-Royce locked up the positions before anyone else arrived.

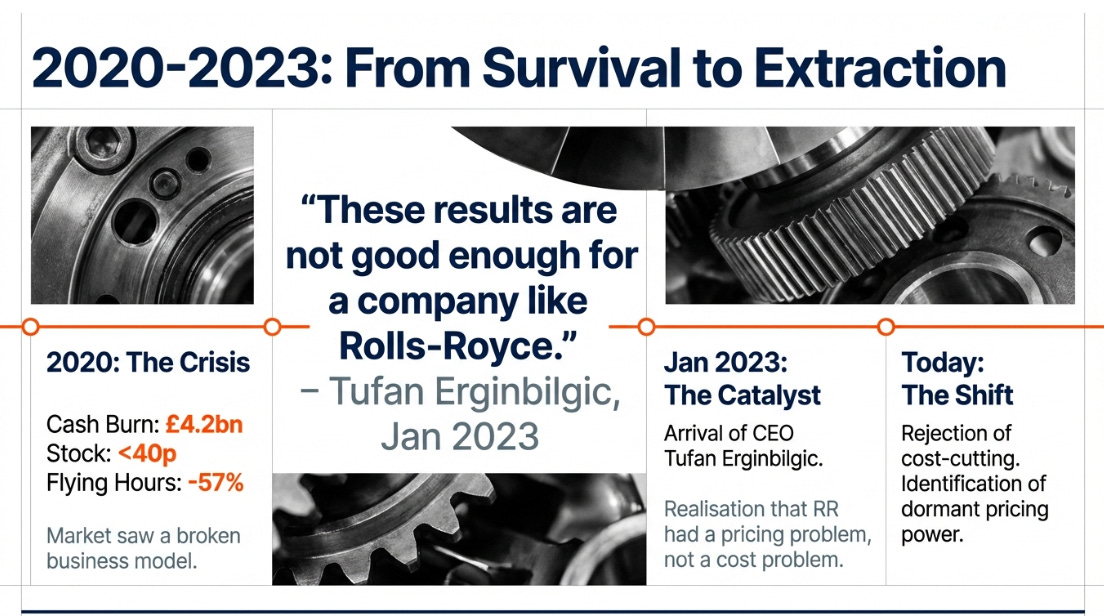

For years, this looked like a catastrophic mistake. Aerospace economics meant selling engines at a loss to capture aftermarket revenue that might materialize decades later. Reliability problems with the Trent 1000 added billions in warranty costs. Then COVID arrived, and flying hours, the metric driving aftermarket revenue, collapsed by 57%.

In 2020, Rolls-Royce burned £4.2 billion in cash. Emergency equity raise. Asset sales. Survival mode. The annuity everyone talked about had stopped paying. The stock fell below 40 pence.

Most turnarounds that follow such crises focus on costs. Cut headcount, close facilities, reduce R&D, shrink the denominator until the math works. When Tufan Erginbilgic took over as CEO in January 2023, the expectation was more of the same.

His first earnings call signaled something different entirely.

“These results are not good enough for a company like Rolls-Royce.”

The bluntness was unusual. The insight behind it was more unusual still. Erginbilgic realized that Rolls-Royce didn’t have a cost problem or a demand problem. It had a pricing problem. The company possessed monopoly power it had spent decades refusing to exercise.

Why? Partly culture, aerospace has always been a long-cycle, relationship-driven industry where aggressive pricing feels unseemly. Partly fear, airlines are sophisticated customers with long memories and loud complaints. Partly inertia, when you’ve underpriced for twenty years, raising prices feels like admitting you were wrong.

Erginbilgic didn’t care about any of that.

Consider the position he inherited. In widebody engines, only two manufacturers exist globally: Rolls-Royce and GE. On the A350 and A330neo, Rolls-Royce has contractual exclusivity, not just market share, but the only option. An airline operating A350s cannot switch to GE. The switching cost isn’t changing suppliers; it’s buying entirely new aircraft.

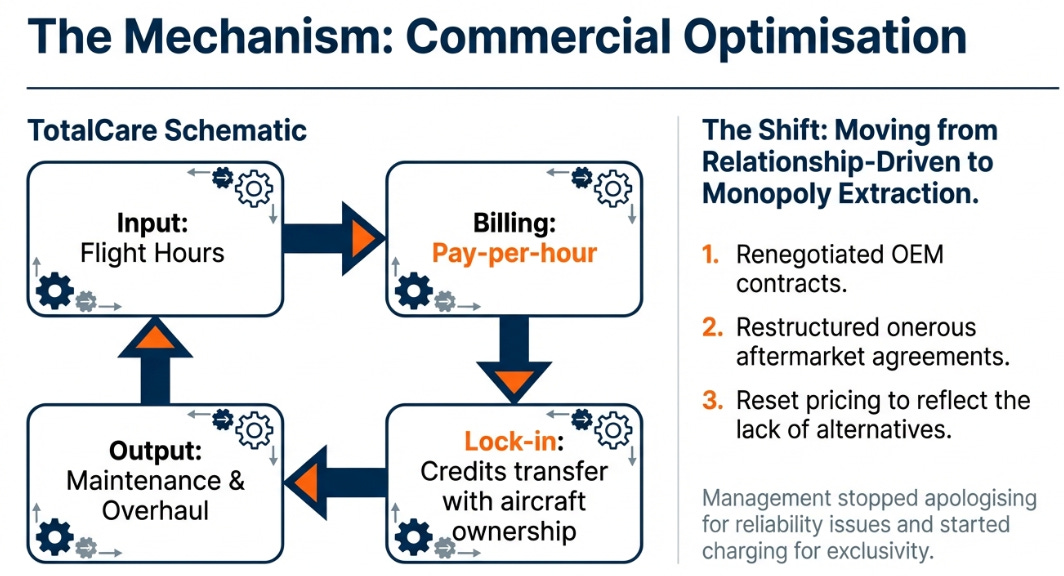

Moreover, airlines had signed TotalCare agreements, contracts spanning twelve or more years where they pay Rolls-Royce per hour flown in exchange for comprehensive maintenance. These include accumulated credits that transfer when aircraft change hands, creating switching costs even for lessors and secondary buyers.

The installed base of 6,000+ engines represented an extraordinary asset, a toll booth on 36% of global widebody aviation, that previous management had neglected to monetize.

“Commercial optimization” became the euphemism for what followed. Every original equipment contract was renegotiated. Onerous aftermarket agreements were restructured. Pricing was reset to reflect the actual value Rolls-Royce provided to customers who had nowhere else to go.

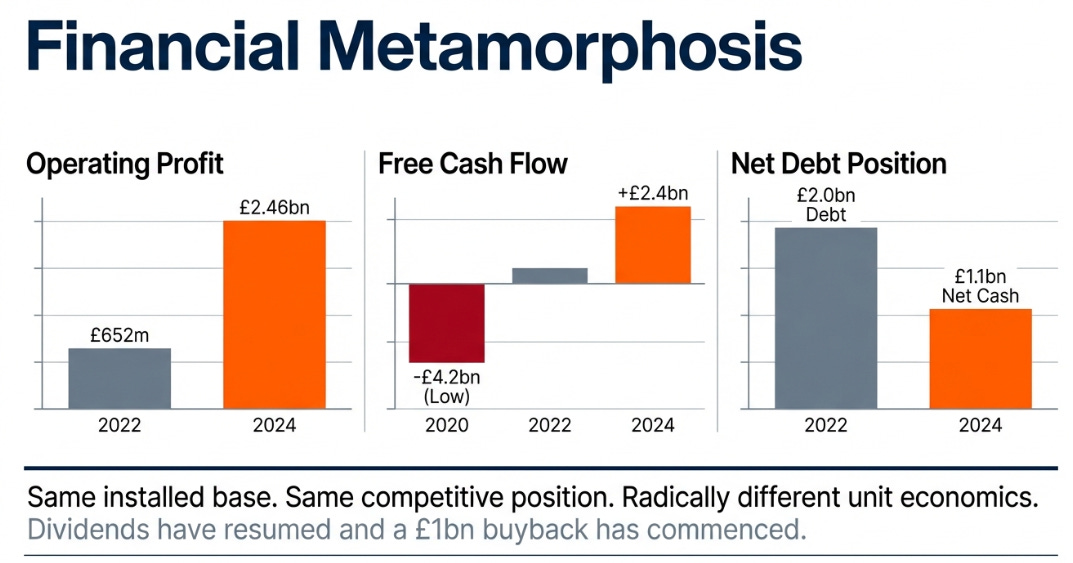

The results were stark. Operating profit rose from £652 million in 2022 to £2.46 billion in 2024. Free cash flow swung from negative £4.2 billion to positive £2.4 billion. The balance sheet flipped from £2 billion net debt to £1.1 billion net cash. Dividends resumed. A billion-pound buyback commenced.

Same installed base. Same competitive position. Same market structure.

Radically different economics.

The Variant Perception

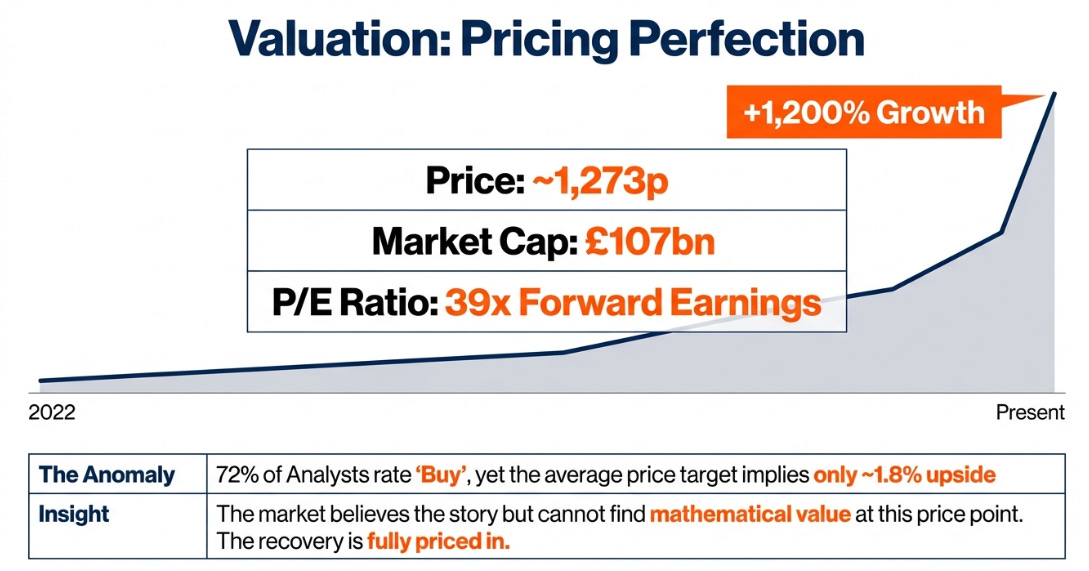

The stock has risen over 1,200% from its 2022 lows, and conventional wisdom now holds that the transformation is “priced in.” Analysts rate the company 72% Buy, yet their average price target sits just 1.8% above the current share price.

This is the tell. Widespread bullishness paired with targets that imply no upside. The Street believes in the story but can’t find more value in the numbers.

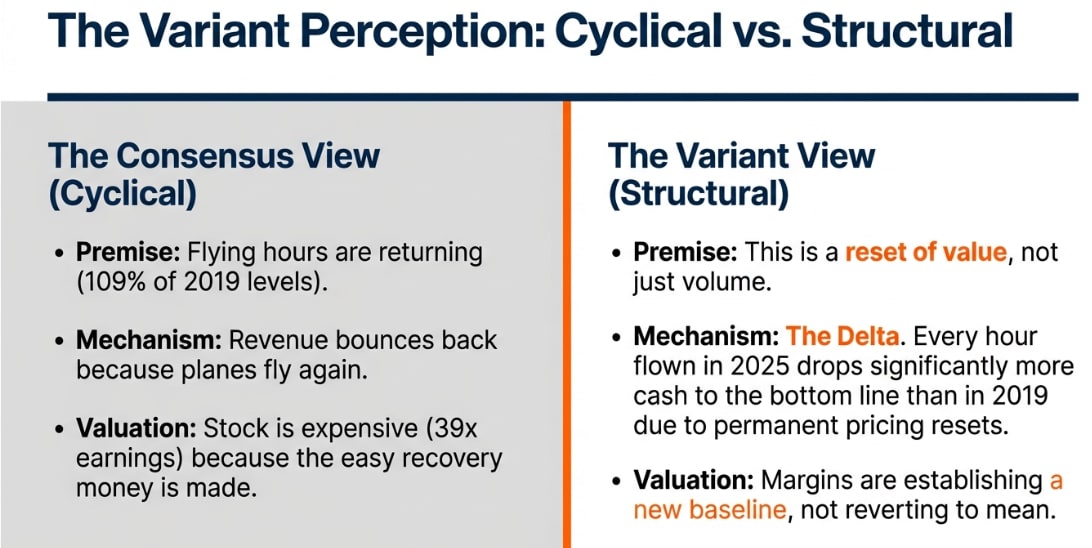

The consensus view treats Rolls-Royce as a cyclical recovery. Flying hours returning to pre-pandemic levels means revenue and cash flow bounce back. The stock is expensive at 39 times forward earnings because it has already captured the rebound.

The variant perception rests on a different reading entirely. This is not a cycle. It is a structural change in unit economics.

Here’s what that means concretely: every hour flown in 2025-2028 drops significantly more cash to the bottom line than an hour flown in 2019. Full stop.

The mechanism is straightforward. On the revenue side, pricing power has been exercised through contract renegotiations that don’t expire or revert. Flying hours are recovering, 109% of 2019 levels in first-half 2025, targeting 130-140% at mid-term. Mix keeps shifting toward higher-margin aftermarket.

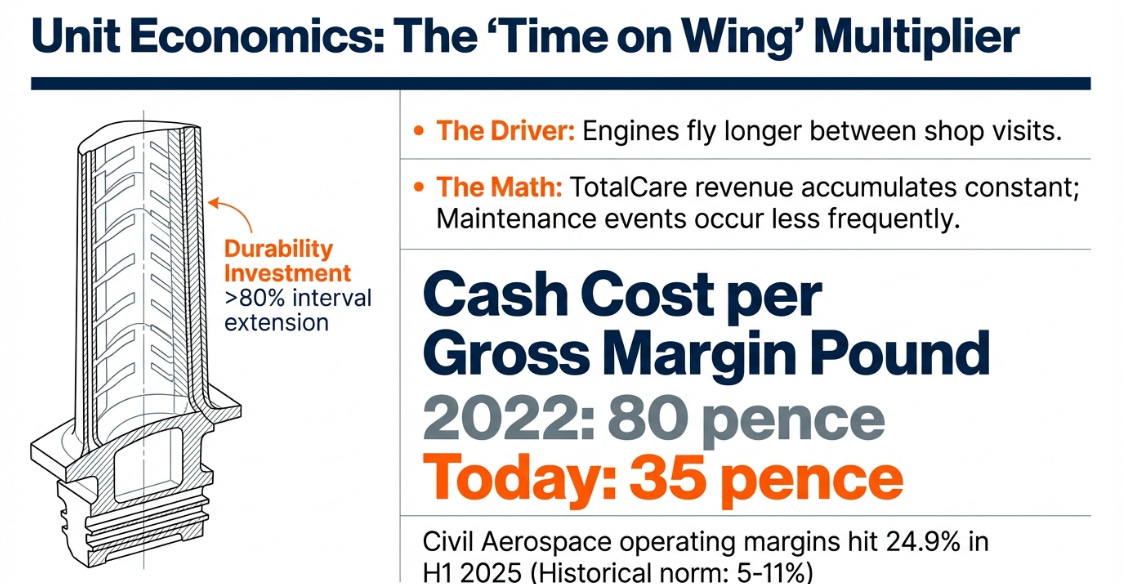

On the cost side, “Time on Wing” investments are extending engine service intervals by over 80%. When engines fly longer between shop visits, TotalCare payments accumulate against fewer maintenance events. The fraction of every gross margin pound eaten by cash costs has dropped from 80 pence in 2022 to 35 pence today, a level management calls best-in-class.

The Civil Aerospace division reported 24.9% operating margins in first-half 2025. Historical norm was 5-11%.

The market is pricing a recovery to normal. The bull case is that this is the new normal.

The bear rebuttal focuses on sustainability. Net contractual improvements contributed £288 million in first-half 2025, a benefit that tapers as renegotiations complete. Management guides to 18-20% margins, not 25%. At 39 times earnings, any disappointment triggers a de-rating.

Both readings are internally consistent. The data doesn’t yet resolve which is correct.

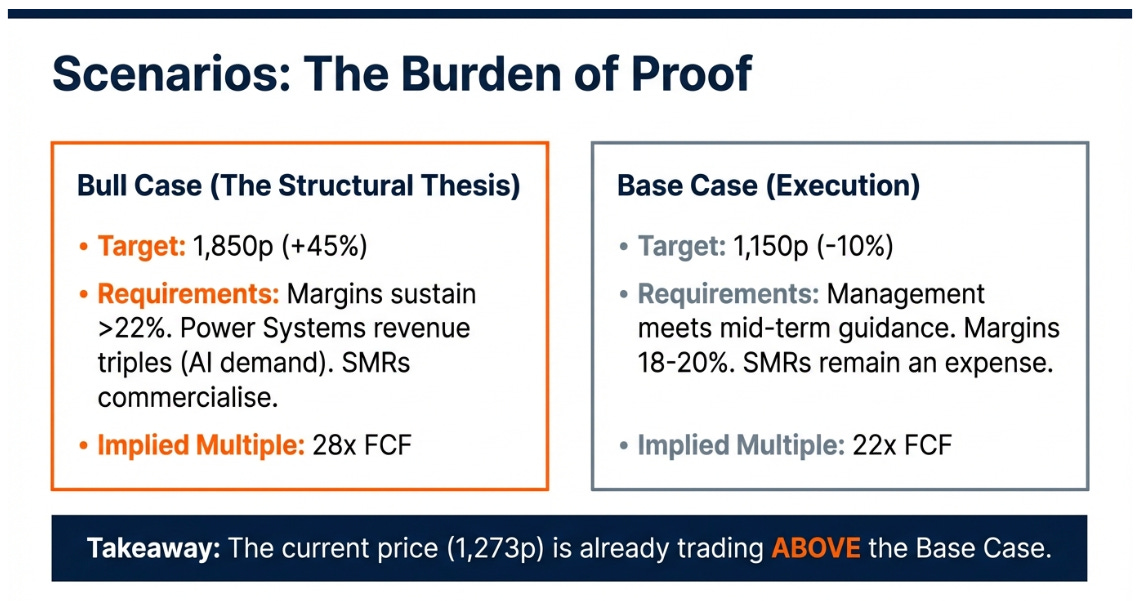

The Three Scenarios

At 1,273 pence and £107 billion market cap, what is the market actually pricing?

Stock prices are expectations about future cash flows. The question isn’t whether Rolls-Royce is a good business, it clearly is. The question is what must be true for today’s price to be justified.

The bull case, 1,850 pence, or 45% upside over three years, requires the structural thesis to prove correct. Margins sustain above 22% even after contractual tailwinds fade. Power Systems, the division selling backup generators to data centers, triples revenue as AI infrastructure buildout continues. Small Modular Reactors reach commercialization milestones. UltraFan secures Airbus’s selection for future narrowbody aircraft.

The numbers: revenue compounds at 11% annually to £27.5 billion by 2028. Operating margins expand to 18.5%. Free cash flow hits £5.5 billion. The market awards 28x on cash flow for a high-quality compounder with optionality.

The base case, 1,150 pence, or 10% downside, is what happens if management simply executes on stated targets. Mid-term guidance met but not exceeded. Margins settle at guided 18-20%. Power Systems grows solidly but data center demand moderates. SMRs remain investment rather than revenue.

The numbers: revenue compounds at 8% to £24 billion. Operating margins reach 16%. Free cash flow hits £4.35 billion, exactly in line with guidance. Multiple compresses to 22x as transformation premium fades.

The implication is uncomfortable. Today’s price already embeds flawless execution. No margin of safety. Total shareholder returns run about 6% annually as dividends and buybacks offset share price decline.

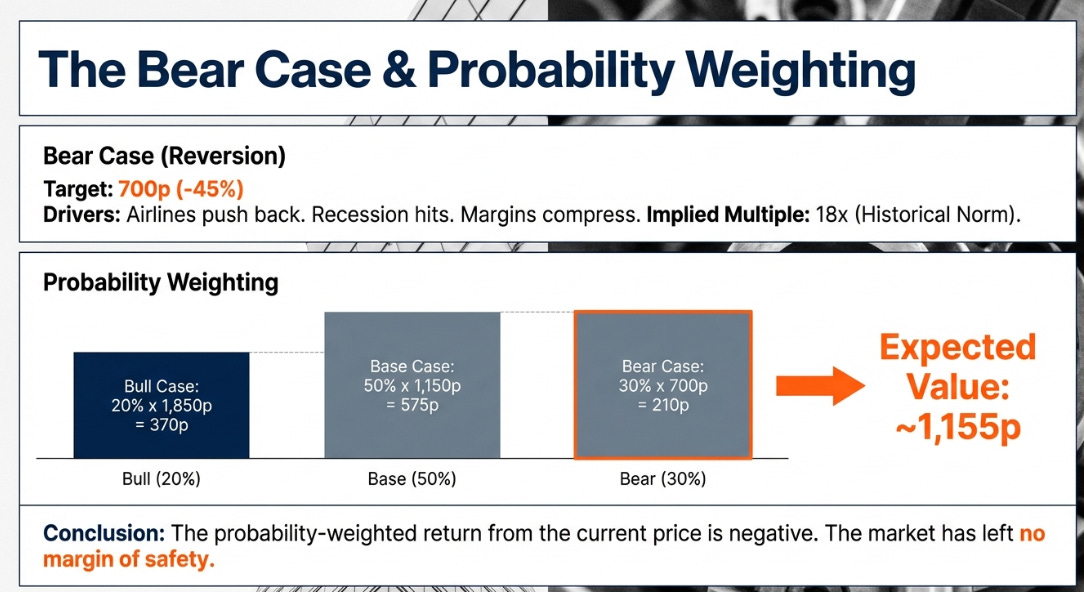

The bear case, 700 pence, or 45% downside, reflects what happens if the transformation proves less durable. Airlines push back on pricing, using future aircraft selections as leverage. Recession hits long-haul premium travel. Data center demand proves cyclical. Margins compress as contractual benefits roll off faster than operational improvements accumulate.

The numbers: revenue compounds at just 4% to £21 billion. Operating margins contract slightly to 13.5%. Free cash flow reaches only £3 billion. Market re-rates to historical aerospace multiples of 18x.

Weighting these scenarios, 20% bull, 50% base, 30% bear, produces an expected value around 1,155 pence. The probability-weighted return from today’s price is negative.

What to Watch

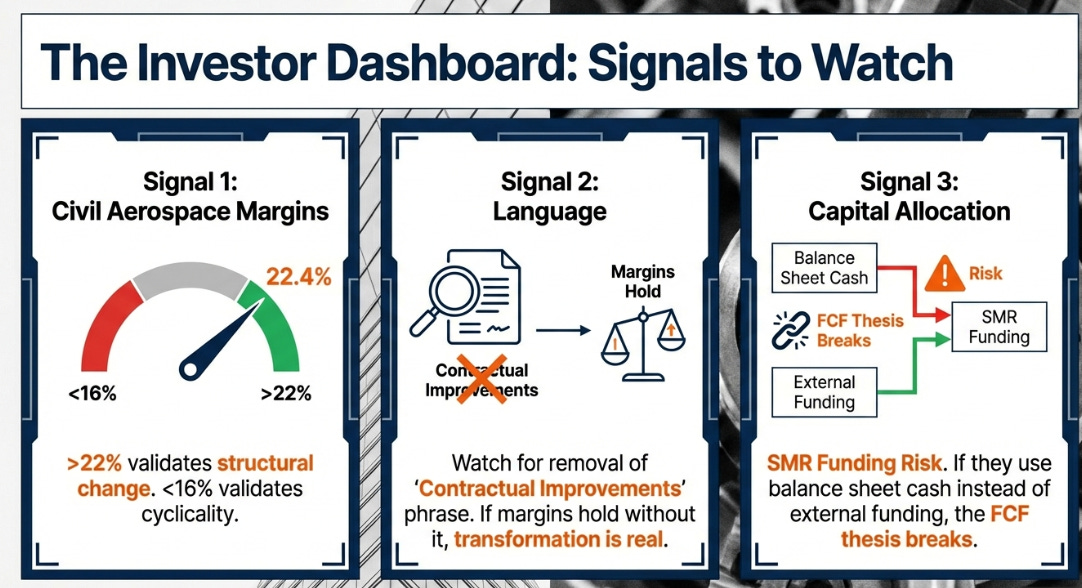

The scenarios resolve themselves through observable signals.

The critical metric is Civil Aerospace margins. Above 22% validates structural change, repricing is permanent, Time on Wing compounds, discipline holds. Below 16% validates the cyclical reading, contractual benefits were one-time, costs rising, transformation less durable than claimed. The 18-22% range is ambiguous.

Power Systems order growth serves as secondary indicator. Above 30% confirms AI infrastructure thesis. Below 5% suggests data center buildout was one-time surge.

Watch management’s language around “contractual improvements.” This phrase has appeared in every earnings release since transformation began. When they stop citing it as a margin driver and margins still hold, structural thesis confirmed. If margins compress as language fades, one-time thesis confirmed.

The hidden risk is capital allocation. Small Modular Reactors are positioned as optionality, government-funded development with future potential. If UK government delays funding, Rolls-Royce must decide: burn its own cash or pause the program. If management starts funding reactors off the balance sheet rather than with external capital, the free cash flow thesis breaks. Transformation CEOs sometimes chase the next transformation. Discipline matters more than ambition.

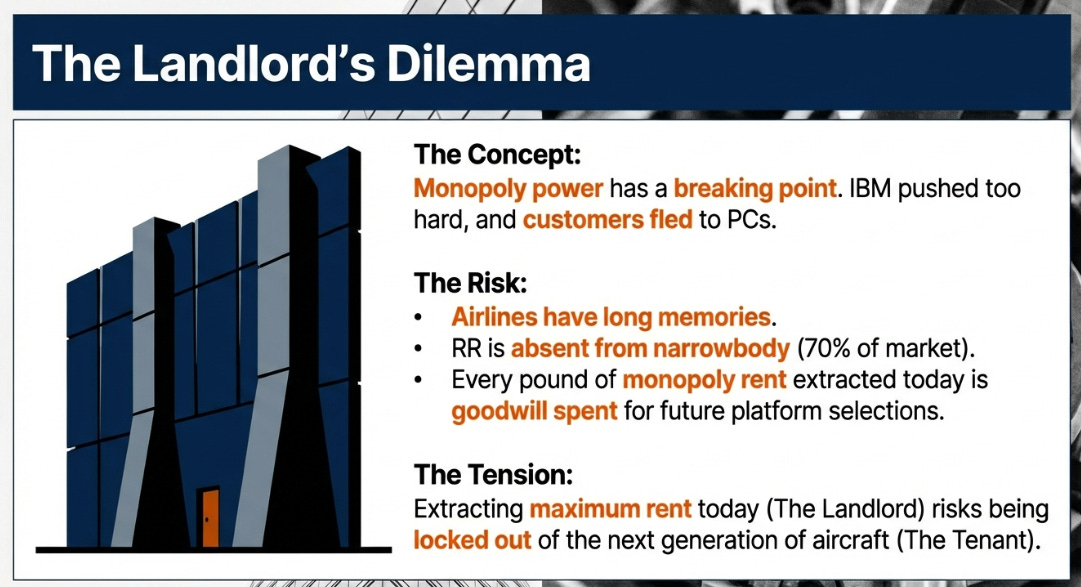

The Landlord’s Dilemma

IBM’s System/360 monopoly eventually faced an existential threat. Not from a better mainframe, no one could build one. From the PC revolution that made mainframes irrelevant. IBM had pushed so hard on mainframe pricing that customers were desperate for alternatives. When alternatives finally arrived, customers fled.

Rolls-Royce faces the same temptation.

They spent a decade building a massive installed base at a loss. They are now entering the harvest phase, aided by a CEO willing to exercise monopoly power. The transformation isn’t really about aerospace or engines. It’s about the gap between having competitive advantage and monetizing it.

But monopoly power comes with risks beyond the obvious. Airlines have long memories. Every pound extracted today is goodwill spent for future selections. Rolls-Royce has no presence in narrowbody, 70% of commercial aviation, and needs to be invited into the next generation of aircraft. Push too hard on widebody pricing, and airlines will lobby for alternatives. Airbus listens to its customers.

For the next three years, the physics of the installed base favors the landlord. Six thousand engines flying millions of hours annually, generating cash with every rotation, operated by customers who signed contracts they cannot exit.

At 1,273 pence, the stock prices perfection. Bull case requires everything right; delivers 45% upside. Base case, flawless execution, delivers 10% downside. Probability-weighted return is negative.

The opportunity for new investors lies not in the thesis but in patience. Quality assets go on sale periodically. Entry point matters more than analysis.

Rolls-Royce has proven it can extract monopoly rents from its installed base. The only question left is whether they’ll recognize the moment before the monopoly starts extracting its price from them.

Disclaimer:

The content does not constitute any kind of investment or financial advice. Kindly reach out to your advisor for any investment-related advice. Please refer to the tab “Legal | Disclaimer” to read the complete disclaimer.