Salesforce 3QFY26 Earnings: The Capacity Discrepancy

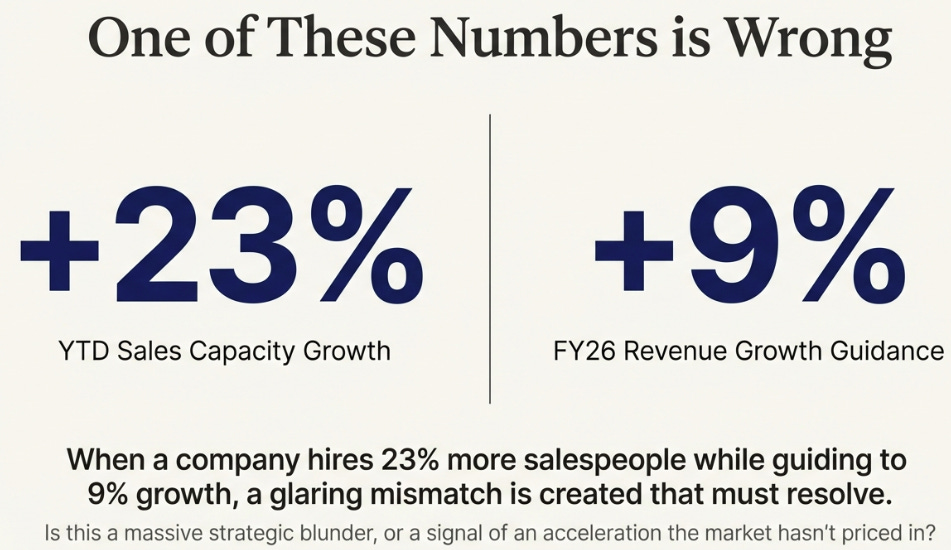

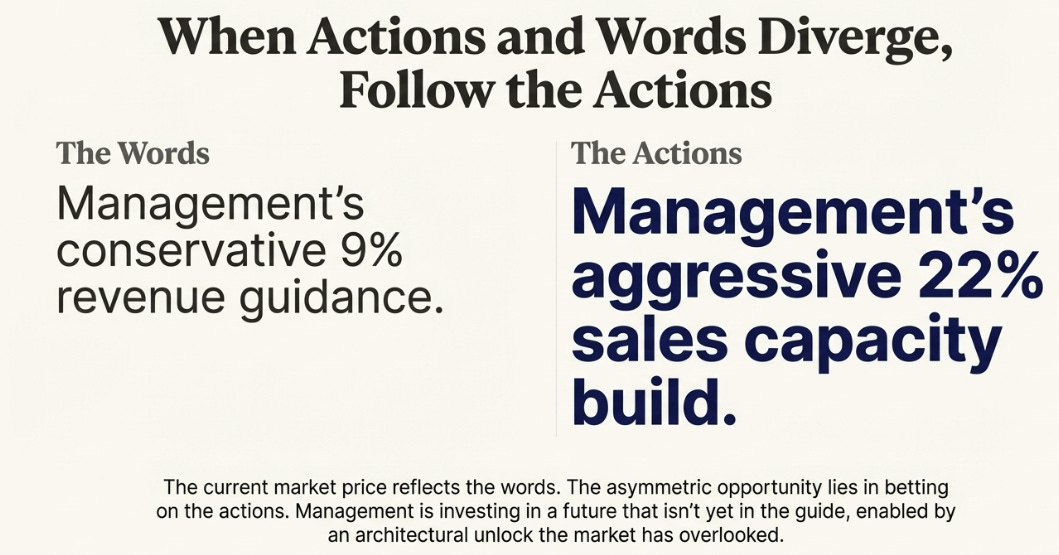

When a company hires 23% more salespeople while guiding to 9% growth, one of those numbers is wrong.

TL;DR:

Salesforce’s largest sales hiring surge in five years is a deliberate bet on FY27 acceleration, not a mistake

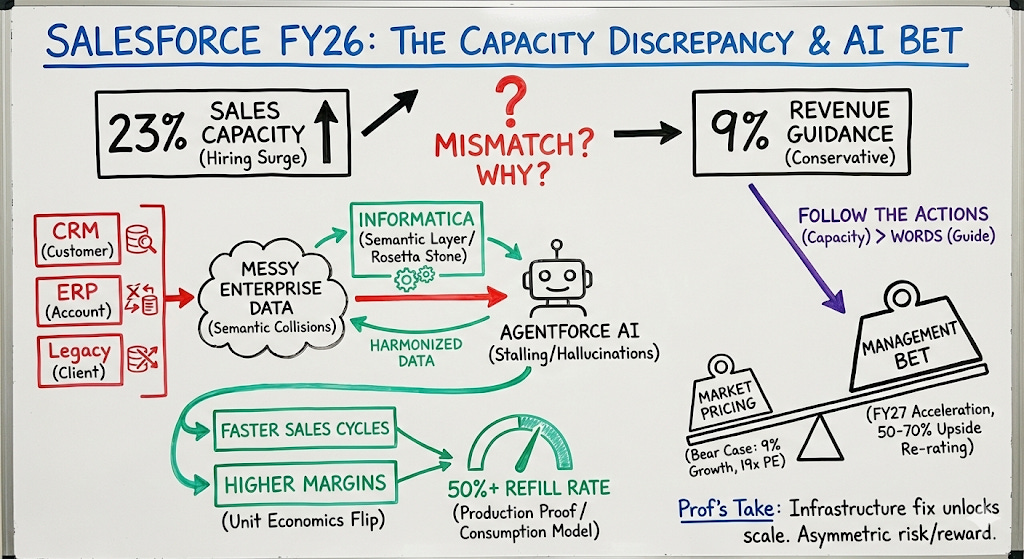

The Informatica acquisition provides the missing semantic layer that finally fixes Agentforce’s scaling bottleneck, transforming unit economics and enabling aggressive hiring.

Early proof is showing up in refill rates and consumption growth, suggesting Salesforce is preparing for FY27 acceleration the market hasn’t priced in.

There’s a question buried in Salesforce’s Q3 earnings call that should have stopped everyone cold. Toward the end of the Q&A, an analyst asked Miguel Milano, the Chief Revenue Officer, about sales capacity. His answer was striking: capacity was up 23% year-to-date, with plans to reach 22% by year-end.

This is the largest sales hiring surge Salesforce has made in five years. The last time they invested this aggressively was during the pandemic boom, when revenue was growing 25% and remote work was pulling forward years of digital transformation. That context made sense. Hire into the surge.

But Salesforce isn’t guiding to 25% growth. They’re guiding to 9%. They’ve spent two years telling Wall Street they’re a mature, disciplined, capital-returning company. They cut 10% of their workforce. They let sales capacity run flat. They pushed margins from the low twenties to 35%. And now, into single-digit growth, they’re suddenly making the largest distribution investment since the pandemic?

The discrepancy is too large to ignore. Either management has lost the discipline they spent two years building, or they’re seeing something in fiscal 2027 that the 9% guide doesn’t reflect. Having spent time with the earnings materials and the transcript, I think it’s the latter. And the reason they can make this bet now, when they couldn’t before, comes down to an acquisition that most analysts dismissed as a legacy data play.

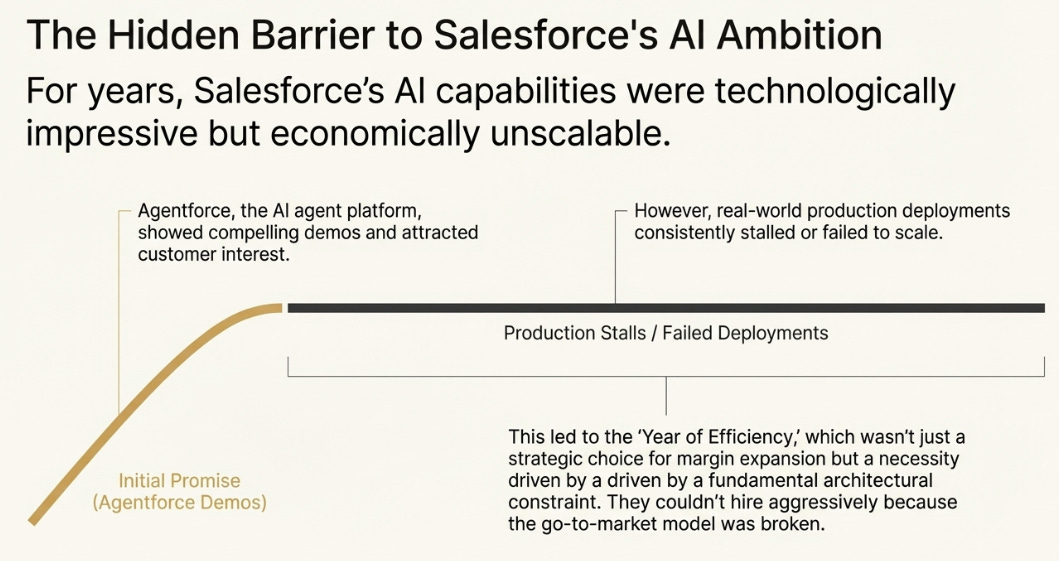

Why Salesforce Couldn’t Scale AI Before

To understand why the Informatica deal matters, you have to understand why Salesforce couldn’t hire aggressively for the past three years — even when they might have wanted to.

The company had built impressive AI capabilities. Agentforce, their agent platform, could process natural language, reason about customer requests, and take actions in enterprise systems. The demos were compelling. Customers were interested. The technology was real.

But production deployments kept stalling. Not because the AI didn’t work in isolation, but because it couldn’t connect reliably to the messy reality of enterprise data.

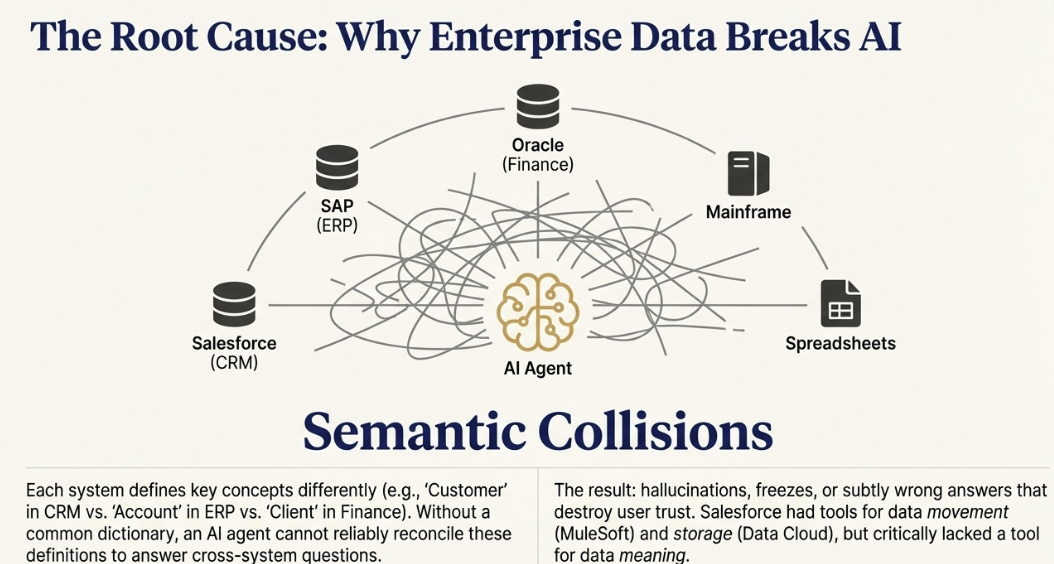

Large companies don’t store customer information in one place. They have Salesforce for CRM, SAP for ERP, Oracle for finance, mainframes for legacy systems, spreadsheets for everything that falls through the cracks. Each system was built at a different time, by different teams, with different assumptions about how to represent basic concepts. What does “customer” mean? It depends which system you’re asking. Is “Customer LTV” in SAP calculated the same way as “Lifetime Value” in the finance system? Almost certainly not.

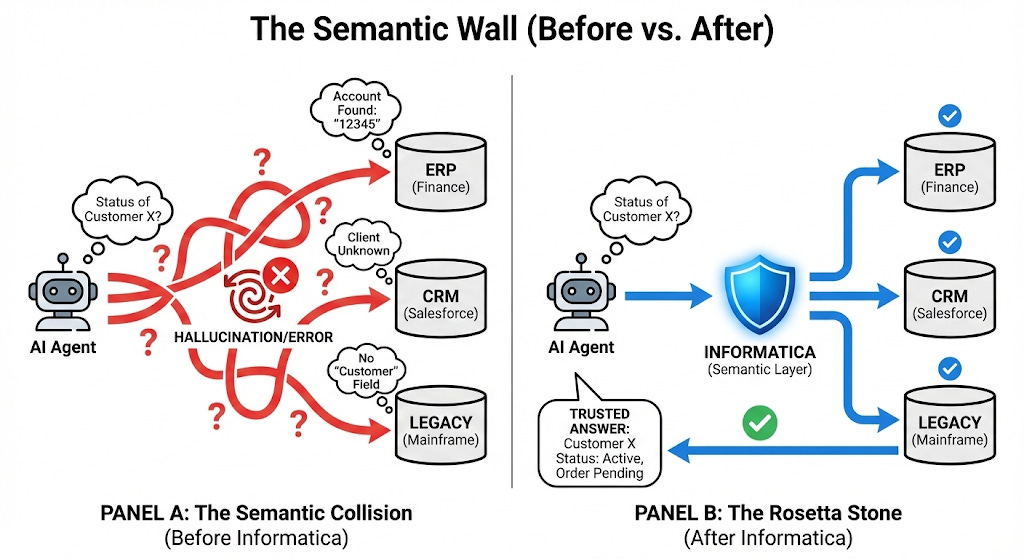

When an AI agent tries to answer a question that spans these systems — “What’s the status of Customer X’s order?” — it runs into semantic collisions. The agent can query each system, but it can’t reconcile the conflicting definitions. It doesn’t know that “Account” in one system refers to the same entity as “Customer” in another. Faced with ambiguity, it either hallucinates a confident answer, freezes entirely, or returns results that are subtly wrong in ways that destroy trust.

Salesforce had tools to move data between systems — that’s what MuleSoft does. They had tools to store and query data — that’s Data Cloud. But they had no tool to understand what the data meant. They were missing the semantic layer, the Rosetta Stone that could translate between the different languages each enterprise system speaks.

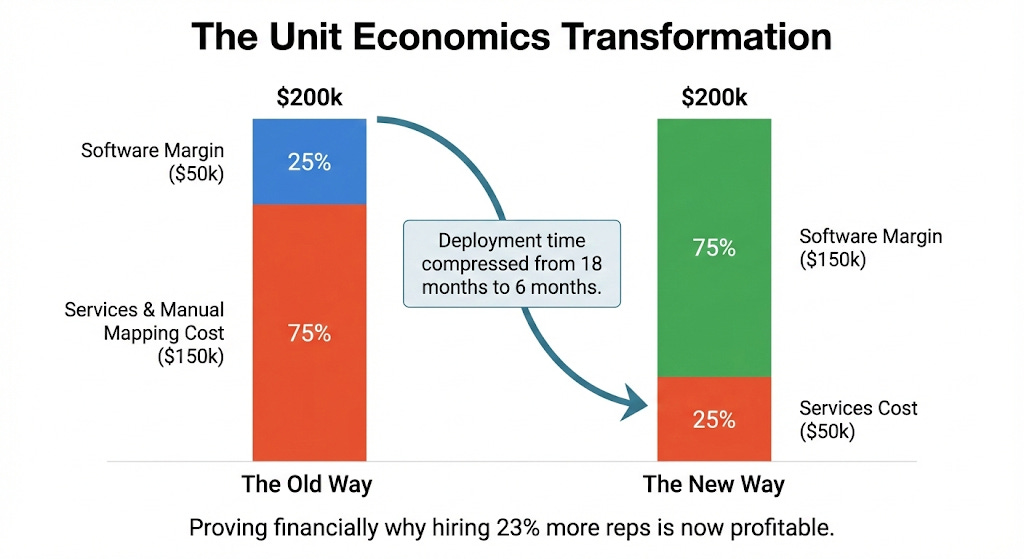

Without that layer, every Agentforce deployment required an army of solution engineers to manually map data definitions. A deal that should have been a straightforward software sale became an 18-month consulting engagement. The professional services cost on a $200K contract might run $150K. The margins were thin. The sales cycles were long. And crucially, the model didn’t scale — hiring more salespeople just meant hiring more solution engineers to support them.

This is why the “Year of Efficiency” wasn’t entirely a choice. It was also a constraint. Salesforce couldn’t invest aggressively in go-to-market because they didn’t have a product that could be sold efficiently. The unit economics were broken at the architecture level.

The Hidden Importance of Informatica

Informatica fixes this, and the way it fixes it explains why the acquisition is more important than the market seems to think.

Informatica isn’t a data integration tool in the traditional sense. It’s a metadata governance engine — software that catalogs every data asset across an enterprise, defines what each field means, and governs who can access what under which conditions. It’s been doing this for 30 years, which means it has pre-built connectors to virtually every legacy system a large company might run, and — perhaps more importantly — trust with the CIOs who run those systems.

When a bank’s technology leader hears “Informatica,” they don’t think “startup integration tool.” They think “the thing that already governs our data.” That trust accelerates sales cycles in ways that are hard to replicate.

But the deeper value is what Informatica does to the unit economics of an Agentforce deal. With a semantic layer in place, the agent can query Informatica’s dictionary to get consistent definitions across systems. It doesn’t need a team of consultants to manually map “Customer” to “Account” to “Client” across fifteen databases. The heavy lifting has already been done.

The numbers shift dramatically. That $200K Agentforce contract that used to require $150K in services? Now it requires maybe $50K. The margin on the deal goes from 25-35% to 60-70%. The sales cycle compresses from 18 months to six. And crucially, the model scales — a sales rep can close more deals per year because each deal requires less implementation support.

This is why Salesforce can suddenly hire 22% more salespeople. The deals are finally profitable at scale. The architecture constraint that prevented aggressive investment in FY24-25 is gone.

The Unit Economics Flip: From Services Drag to Scalable Consumption

The unit economics argument is compelling in theory, but theory doesn’t move stocks. What moves stocks is evidence that the theory is working in practice. And buried in the earnings call, there’s a metric that provides exactly that evidence.

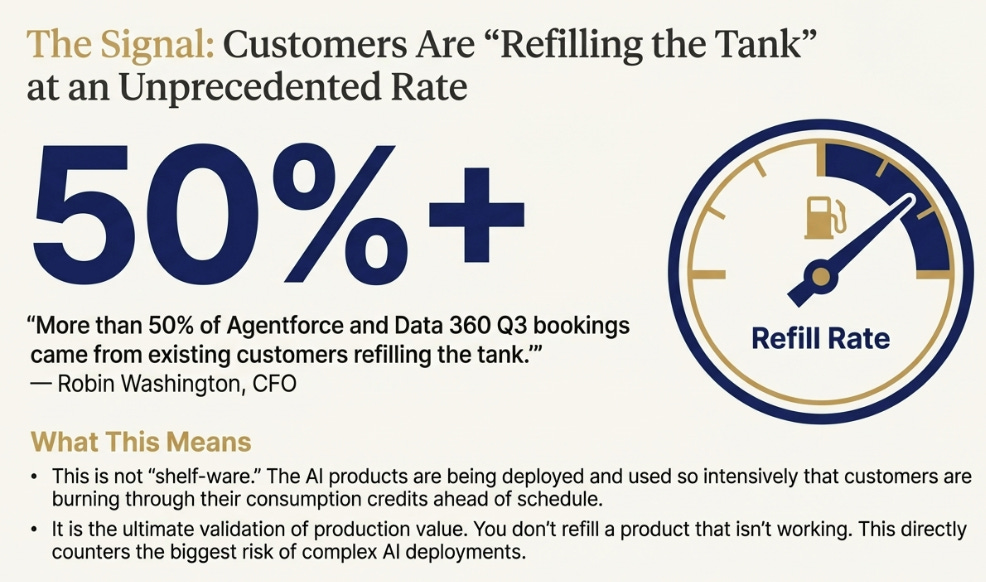

Robin Washington, the CFO, mentioned almost in passing that “more than 50% of Agentforce and Data 360 Q3 bookings came from existing customers refilling the tank.” That’s 362 customers coming back for more before their initial contracts expired.

This number deserves more attention than it’s getting.

Enterprise software graveyards are filled with products that were purchased but never deployed. The shelf-ware problem is real, especially for AI products that promise transformation but deliver complexity. If Agentforce were following that pattern — bought with enthusiasm, deployed with difficulty, abandoned with regret — you wouldn’t see refills. You’d see churn, or at best flat renewals.

The Signal in the Refill Rate

A 50%+ refill rate means the opposite is happening. Customers are burning through their Agentforce consumption credits fast enough to need more. The agents are in production, doing real work, delivering enough value that customers want to expand usage. The architecture is holding under real-world conditions.

This is the production validation of the Informatica thesis. If the semantic layer weren’t working — if agents were hitting data ambiguities and hallucinating — customers would pull back. They wouldn’t refill; they’d reduce. The fact that refills are running above 50% of bookings suggests the opposite: the Rosetta Stone is translating accurately, and customers are leaning in.

Think of it as the equivalent of GPU utilization rates in an AI training cluster. You can have the most powerful chips in the world, but if the networking bottleneck means they’re sitting idle 80% of the time, the system doesn’t work. Nvidia’s Mellanox acquisition mattered because it solved the networking bottleneck and let GPU utilization soar. The refill rate is Salesforce’s utilization metric — proof that the semantic bottleneck has been addressed and the agents are actually working.

The Mellanox Parallel: Infrastructure That Unlocks a New Market

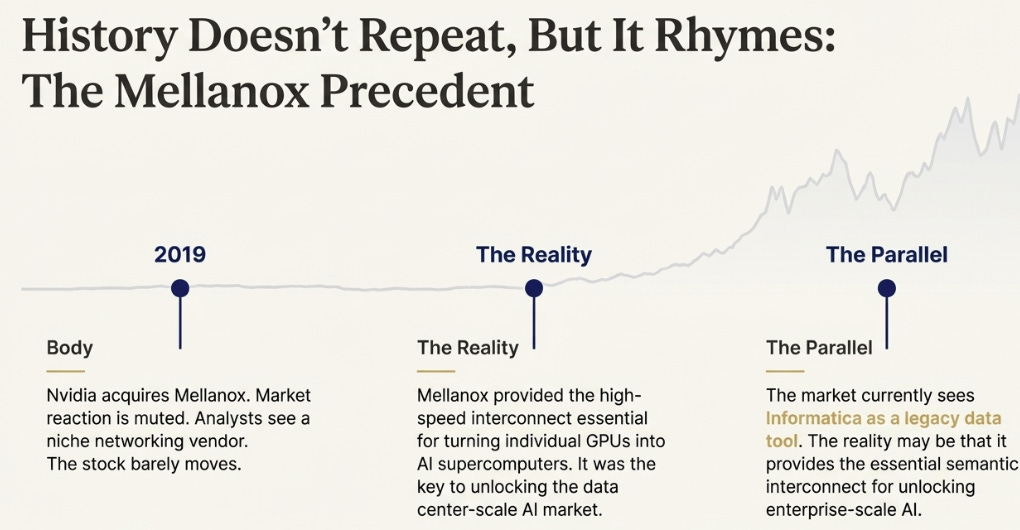

The Mellanox parallel is worth dwelling on for a moment, because it illustrates how markets systematically misprice infrastructure acquisitions.

When Nvidia announced the Mellanox deal in 2019, the reaction was muted. Nvidia was understood as a GPU company riding the gaming and crypto waves; Mellanox was a niche networking vendor selling InfiniBand switches to supercomputing labs. Analysts called it a reasonable deal at a fair price. The stock barely moved.

Five years later, that “boring infrastructure acquisition” looks like one of the most consequential tech deals of the decade. Mellanox gave Nvidia the high-speed interconnect needed to turn thousands of individual GPUs into one giant, efficient AI supercomputer. Without it, Nvidia would sell chips. With it, Nvidia sells data centers. The difference is roughly $2 trillion in market cap.

The market missed Mellanox because “AI at hyperscale” wasn’t the dominant narrative yet. The bottleneck that Mellanox solved — network latency between GPUs in large clusters — only became acute when AI training runs exploded in size. The strategic value was real from day one, but it took a paradigm shift to make it obvious.

I suspect something similar might be happening with Informatica. The bottleneck it solves — semantic confusion between enterprise data systems — only becomes acute when AI agents move from demos to production deployments. We’re in the early innings of that transition. The 50% refill rate and 330% Agentforce ARR growth suggest it’s happening, but the full impact is still ahead.

At $238, Salesforce trades at 19 times forward earnings. The market prices it as a mature CRM company with modest AI upside. If the Informatica parallel to Mellanox holds — if the semantic layer becomes as important to enterprise AI as the networking layer became to AI infrastructure — that multiple is far too low.

The FY26 Hiring Surge and the Shift to Consumption Revenue

There’s one more dimension to the FY26 hiring surge that makes it structurally different from previous cycles, and it has to do with the revenue model itself.

When Salesforce hired aggressively in fiscal 2021, they were hiring to sell seats. More reps meant more CRM licenses. The revenue scaled linearly — double the sales force, get somewhat less than double the revenue due to ramp time and territory overlap. The math was straightforward and the ceiling was visible.

In fiscal 2026, Salesforce is hiring to sell consumption. Agentforce isn’t priced primarily by seat; it’s priced by tokens processed, conversations handled, agent actions executed. Each deployment creates a refill cycle as customers burn through credits and come back for more.

The math is fundamentally different. A rep selling seats adds ARR that renews annually. A rep selling consumption adds ARR that compounds as usage expands within the account. The customer doesn’t just renew at the same level — they “refill the tank” at higher levels as they deploy agents to more use cases and automate more workflows.

Milano quantified the opportunity during the call: “Agentforce and Data Cloud is going to add 10, 20% on the business we do with every customer.” If that’s accurate, each rep isn’t just acquiring new logos — they’re expanding wallet share across Salesforce’s entire installed base of 150,000+ customers. A customer paying $500K for Sales Cloud becomes a customer paying $600K after Agentforce. Multiplied across the base, the numbers get large quickly.

The +22% capacity surge is a bet that consumption economics compound faster than seat economics ever did. Management isn’t just hiring to maintain market share; they’re hiring to capture a new revenue stream that layers on top of the existing business.

The Kill Switches: How This Thesis Could Be Wrong

Every investment thesis needs kill switches — specific, measurable conditions that would prove the thesis wrong. Here are the ones I’m watching:

If the refill rate drops below 40%, it means agents aren’t working well enough in production to drive expansion. The architecture thesis is wrong.

If cRPO growth decelerates below 9% for two consecutive quarters despite 22% more sales capacity, it means the pipeline isn’t converting. The hiring was a mistake.

If Salesforce discloses AI gross margins and they’re below 60%, it means the consumption model is margin-dilutive. The unit economics don’t actually work at scale.

If sales productivity stays flat or declines through fiscal 2027, it means the new reps aren’t ramping. Informatica isn’t enabling the go-to-market as expected.

These aren’t abstract risks; they’re the specific ways the thesis could fail. If you see these metrics breaking, reduce the position. The architecture unlock either works or it doesn’t, and these numbers will tell you which.

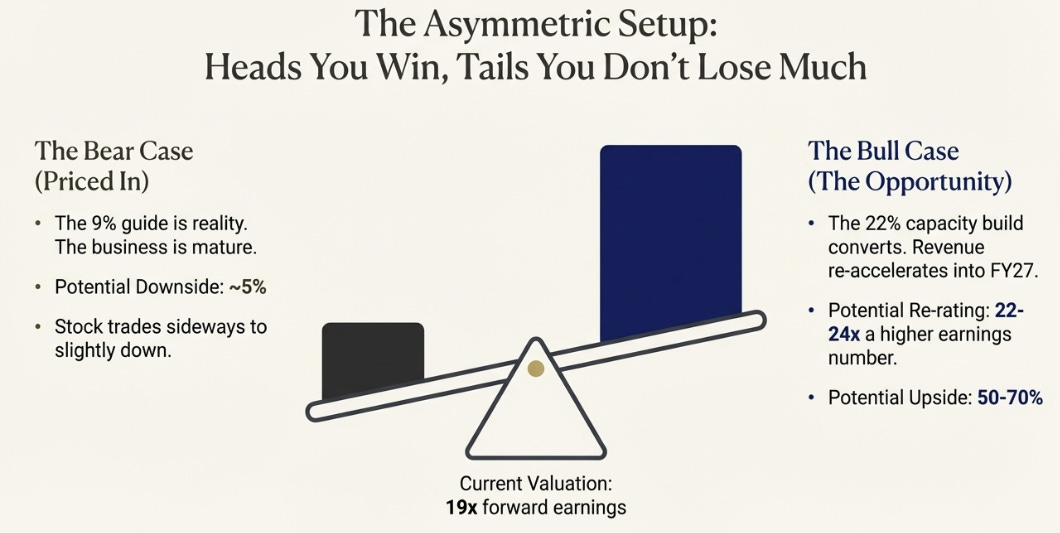

The Asymmetric Setup for FY27

The setup, then, is this: Salesforce is making a bet that the market isn’t pricing.

The 9% revenue guide reflects the current sales force and the current pipeline. It’s the conservative number, the one management can control and beat.

The 22% capacity increase reflects what management actually believes about fiscal 2027. You don’t make that investment into single-digit growth unless you see acceleration coming. Enterprise software companies are too disciplined, too margin-conscious, too Wall Street-trained to throw money at speculation.

One of these numbers is wrong. Either the capacity investment is a mistake and margins will compress as excess reps underperform, or the guide is conservative and revenue will re-accelerate as the new capacity comes online.

The refill rate suggests the latter. The Informatica unit economics suggest the latter. The Mellanox precedent suggests markets systematically miss these kinds of infrastructure-driven inflections.

At 19 times forward earnings, the market prices the bear case: perpetual 9% growth, mature business, bond-like characteristics. If that’s right, the stock trades sideways to down slightly. You lose maybe 5%.

But if the capacity converts — if the architecture change enables the go-to-market acceleration management is betting on — the stock re-rates to 22-24 times a higher earnings number. That’s 50-70% upside.

The asymmetry is what makes the position interesting. You’re not betting on a specific outcome with certainty. You’re betting that the capacity discrepancy has to resolve, and that at current prices, you’re getting the resolution for free.

I’m inclined to bet on the number management can’t hide — the 22% capacity build — over the number they can manage — the 9% guide. When actions and words diverge, follow the actions.

Disclaimer:

The content does not constitute any kind of investment or financial advice. Kindly reach out to your advisor for any investment-related advice. Please refer to the tab “Legal | Disclaimer” to read the complete disclaimer.

This framing of Informatica as a semantic layer solvingan architecture bottleneck is brillant. Your point about the refill rate being essentially a utilization metric really crystallizes why this is differnet from typical enterprise software rollouts. What's interesting is that the 22% capacity build also suggests Salesforce might be preparing for the network efects of agent-to-agent interaction within customer ecosystems, where onecustomer deploying agents creates API pressure on their partners to do the same.