Sandisk 2QFY26 Earnings: The Confession

SanDisk's earnings prove what Jensen Huang admitted on stage: the GPU highway needs on-ramps, and there's only one material that can pave them.

TL;DR

AI broke the memory hierarchy: HBM is too small, HDDs are too slow, and enterprise SSDs are now architecturally required, not optional.

SanDisk’s Q2 numbers confirm pricing power: 35–57% sequential ASP increases, 65–67% gross margin guidance, and demand in allocation.

This isn’t a normal NAND cycle: SSDs are being co-designed into NVIDIA, Google, and Amazon silicon, creating stickiness and inelastic demand.

The Problem

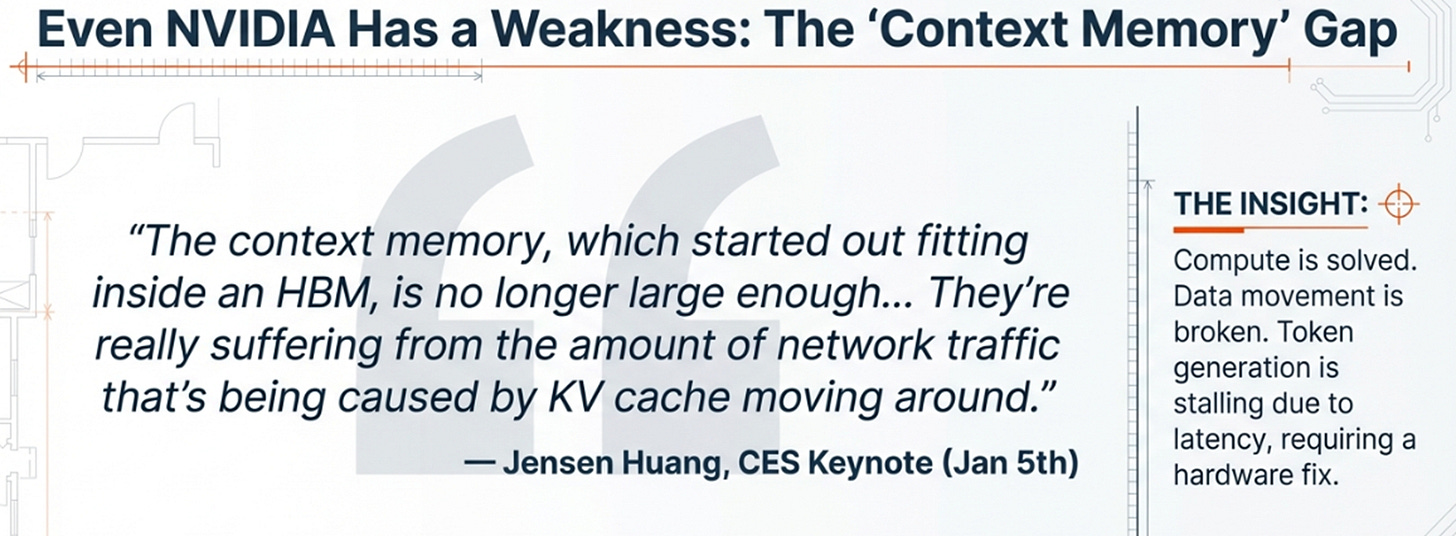

On January 5th, three weeks before SanDisk reported earnings, Jensen Huang stood on stage at CES in Las Vegas and made a confession.

He wasn’t talking about SanDisk. He wasn’t talking about NAND flash or storage economics or memory hierarchies. He was describing a problem that NVIDIA, the most valuable semiconductor company in history, couldn’t solve with chips alone.

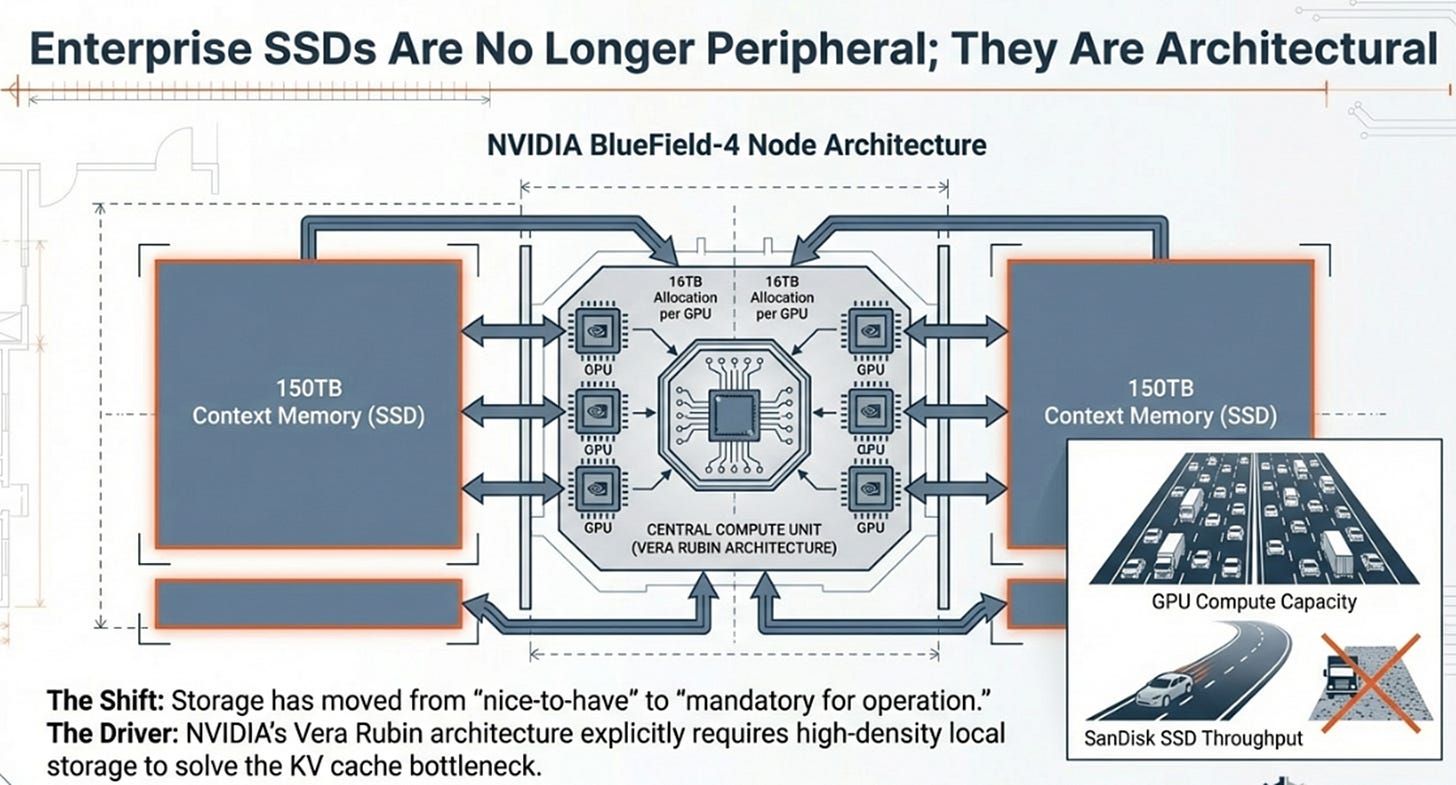

“The context memory, which started out fitting inside an HBM, is no longer large enough,” Huang explained, walking the audience through the architecture of Vera Rubin, NVIDIA’s next-generation AI supercomputer. “They’re really suffering from the amount of network traffic that’s being caused by KV cache moving around. This is a pain point for just about everybody who does a lot of token generation today.”

The solution NVIDIA built was BlueField-4: 150 terabytes of context memory per node, allocating 16 terabytes to each GPU. What sits behind that specification is enterprise SSDs, not as peripheral storage bolted onto the side of the system, but as mandatory architecture embedded directly into the compute fabric.

This is the confession: NVIDIA solved compute spectacularly. They built twenty-lane GPU highways. But the on-ramps to those highways are still gravel roads.

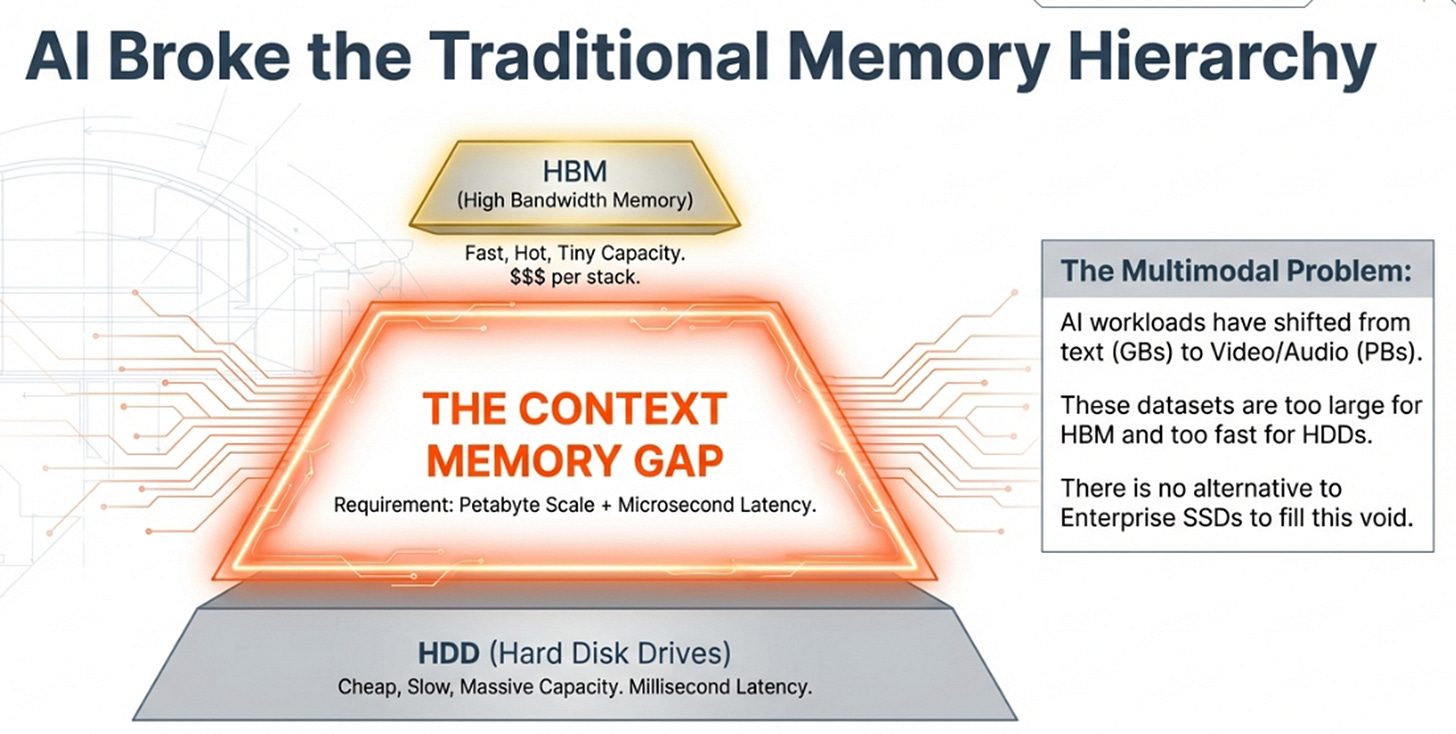

The memory hierarchy has a gap. At the top sits High Bandwidth Memory , blindingly fast, absurdly expensive at hundreds of dollars per stack, and physically constrained by how many layers you can stack before thermal limits dominate. At the bottom sit hard disk drives , cheap per terabyte but catastrophically slow, delivering milliseconds of latency when GPUs need microseconds.

In between? Nothing that works at scale. Nothing except enterprise SSDs.

When AI meant text models measured in gigabytes, the gap was manageable. When AI shifted to multimodal workloads , video, high-resolution imagery, audio , data volumes exploded into petabytes. Petabytes cannot economically live in HBM. Petabytes cannot wait for spinning disks. Enterprise SSDs are the only technology that delivers both the capacity and speed that AI requires.

Jensen designed SSDs into Vera Rubin because there was no alternative. Three weeks later, SanDisk reported fiscal Q2 earnings.

The Proof

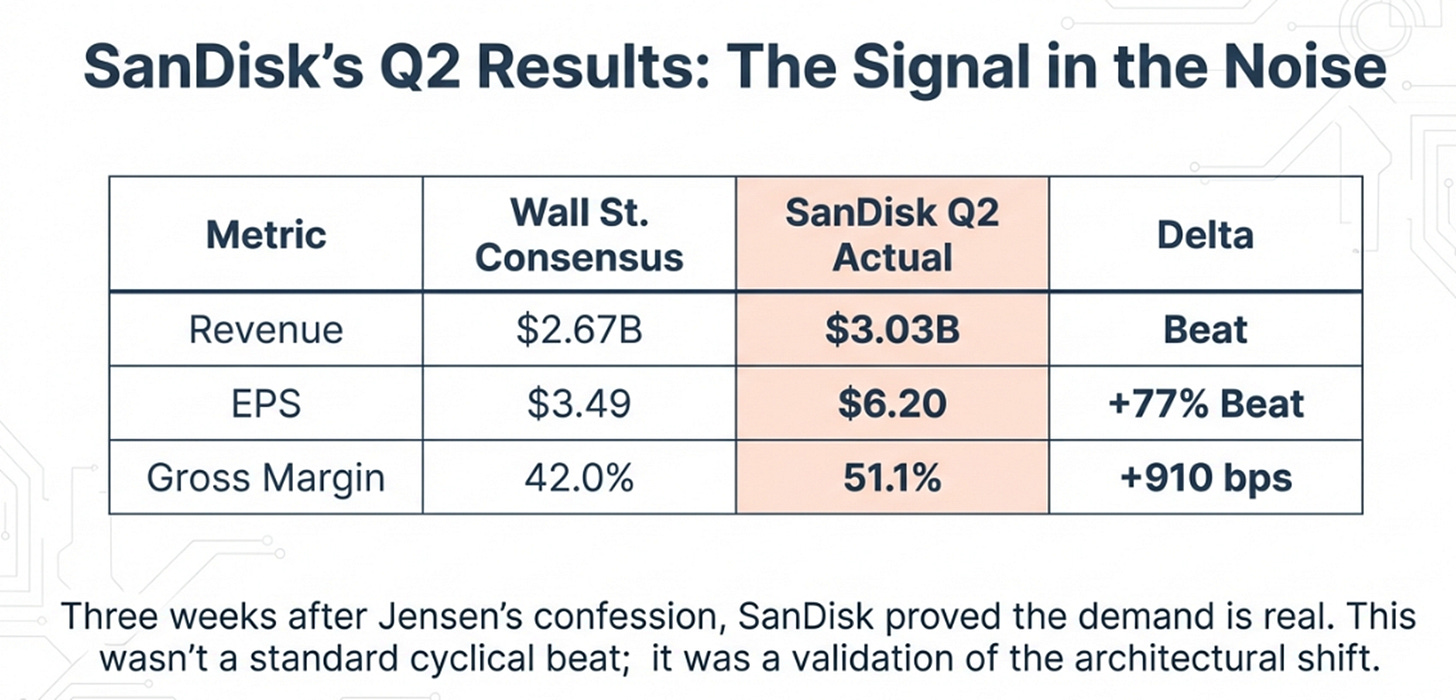

The headline numbers were impressive: revenue of $3.03 billion versus expectations of $2.67 billion, earnings of $6.20 per share versus expectations of $3.49, gross margins of 51.1% versus expectations of 42%.

But the guidance is the story.

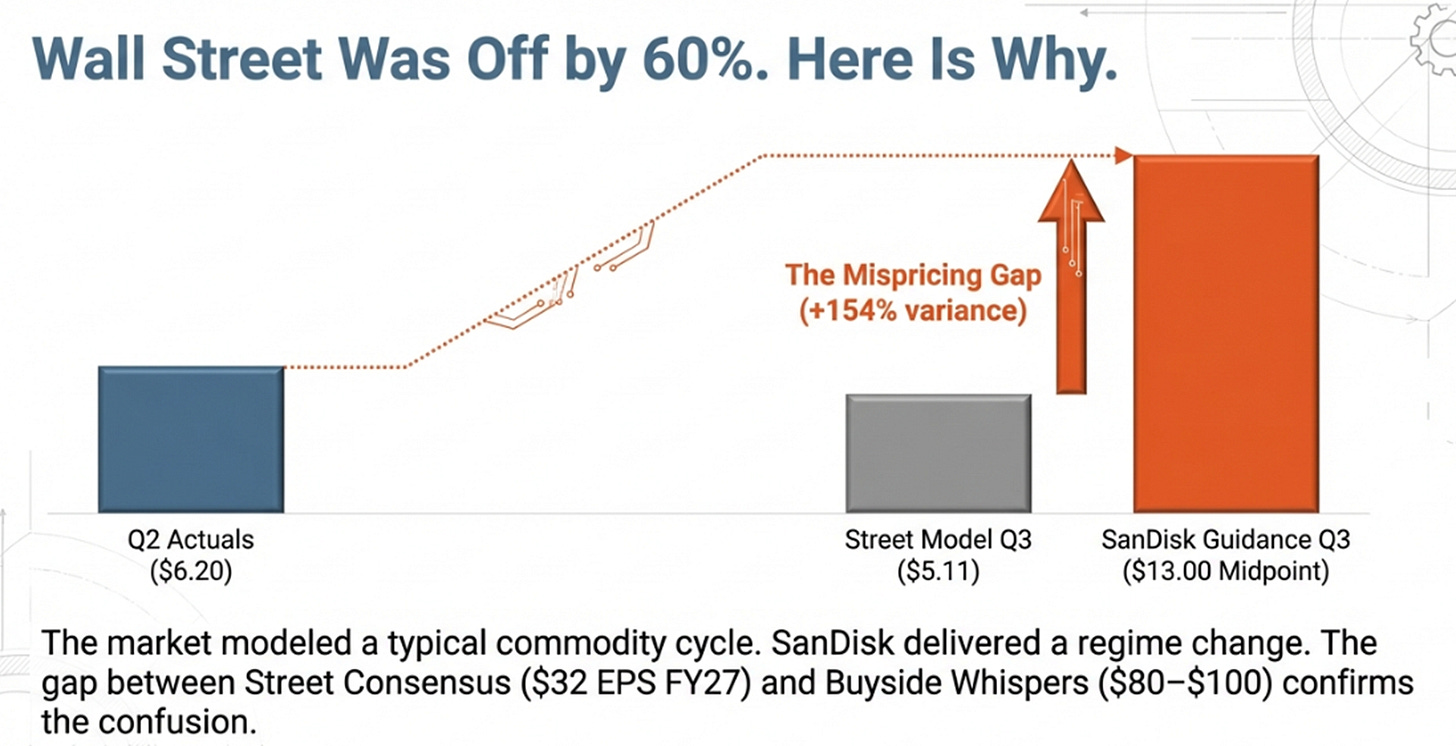

For the March quarter, SanDisk expects revenue of $4.4 to $4.8 billion. Wall Street was modeling $2.9 billion. The company expects earnings of $12 to $14 per share. Wall Street was modeling $5.11. Gross margins are expected to reach 65% to 67%.

The street was off by more than sixty percent.

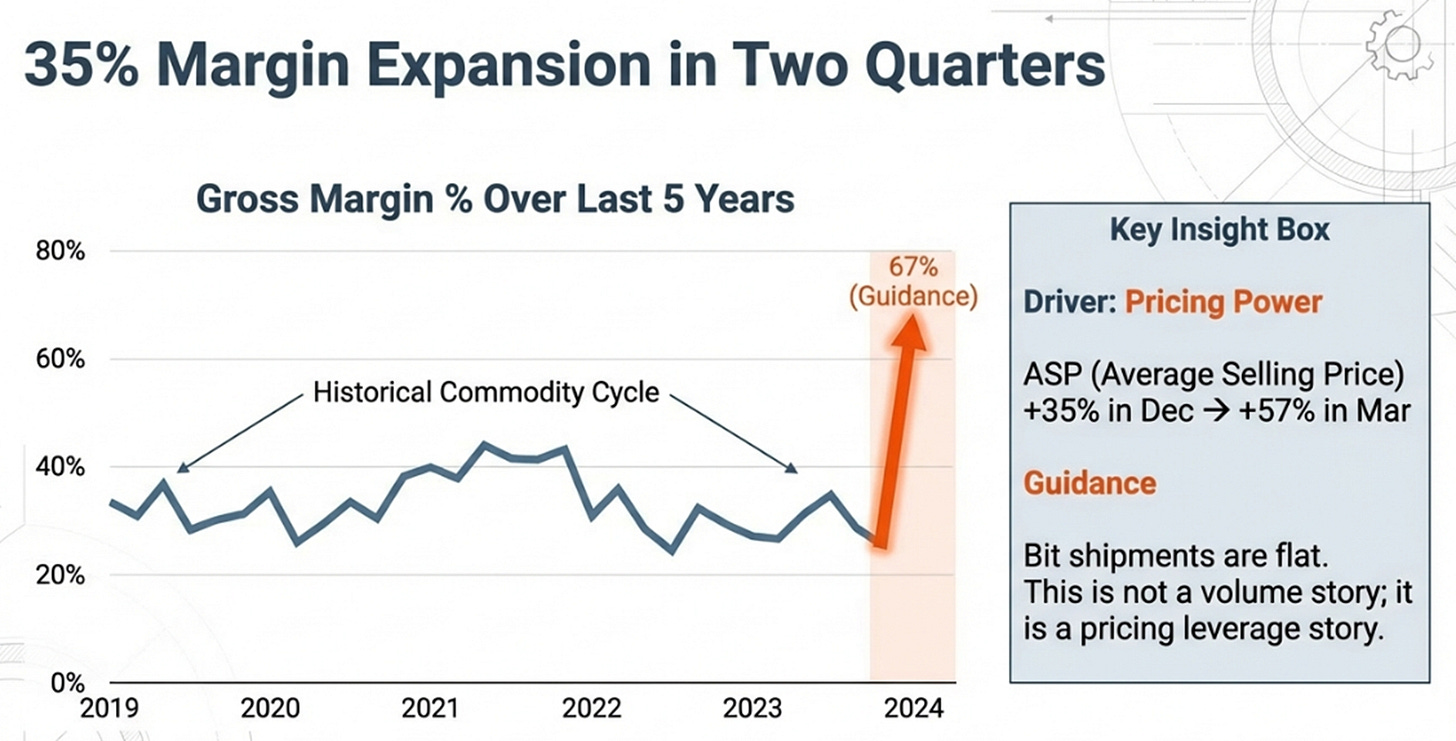

Consider the margin trajectory: 29.9% in the September quarter, 51.1% in December, and now guidance for 65-67% in March. That is thirty-five percentage points of gross margin expansion in two quarters. In NAND flash. An industry where margins historically oscillated between 25% and 45% across entire cycles.

What’s driving it? Pricing power. Average selling prices rose 35% sequentially in the December quarter. They’re guided to rise another 57% in March. Bit shipments increased only low-single digits. This is not a volume story. This is a company that can raise prices because customers have no alternative.

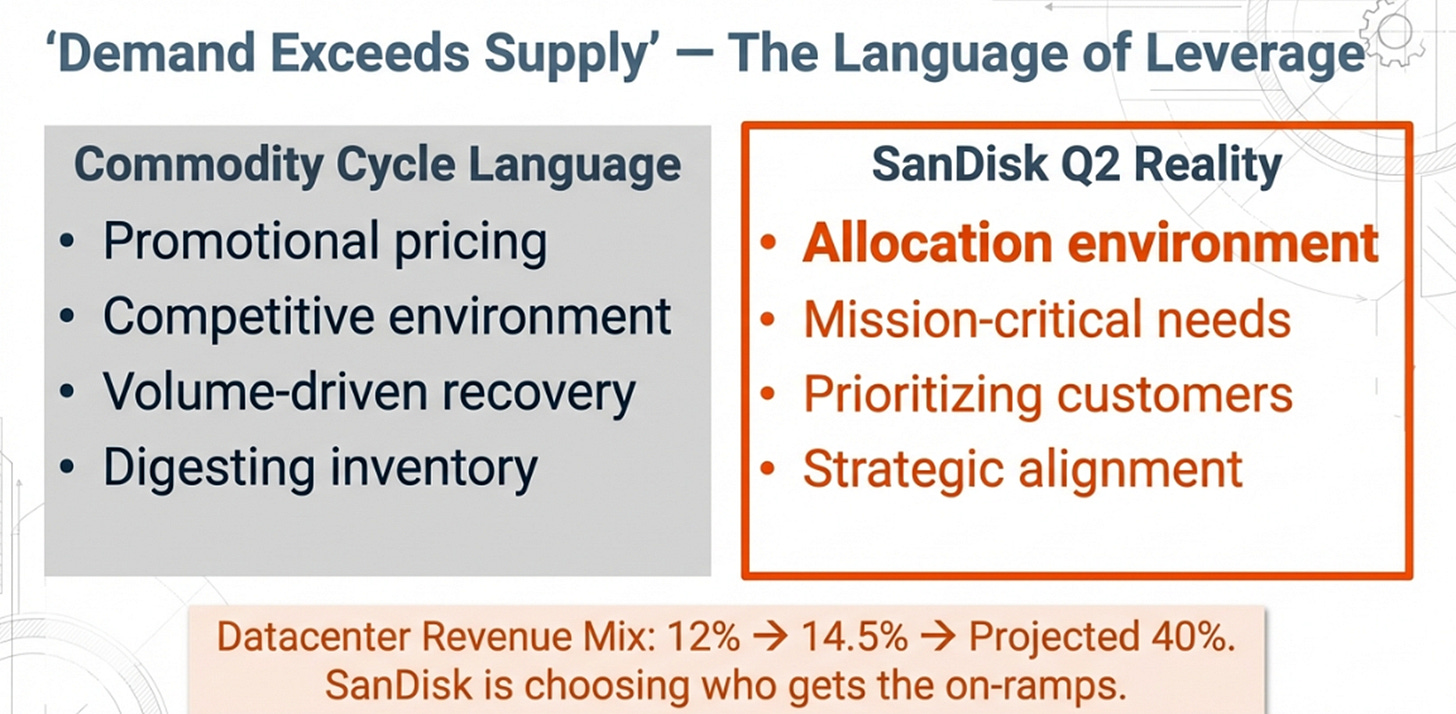

Management’s language confirmed it. They described operating in an “allocation environment” , meaning they are choosing which customers to serve, not competing for orders. They are prioritizing “mission-critical customer needs” within available supply. That is not how commodity suppliers talk.

The mix shift validates the architecture story. Datacenter revenue grew 64% sequentially to $440 million, now representing 14.5% of total revenue, up from roughly 12% the prior quarter. PCIe Gen5 high-performance drives completed qualification at a second hyperscaler. Stargate , presumably the architecture that will power major AI deployments, is advancing through qualification with two major hyperscalers, with revenue shipments expected within several quarters.

Jensen described SSDs architected into compute fabric as the solution to NVIDIA’s KV cache problem. SanDisk is qualifying for exactly that architecture. The demand he identified is real, and it is accelerating.

The Variant Perception

After a 1,400% gain since spinning off from Western Digital eleven months ago, the natural assumption is that the market has figured this out. Consensus, however, still believes this is a cycle , a spectacular one, but a cycle nonetheless.

The consensus view: NAND is a commodity. Cycles always revert. Samsung will respond to 65% gross margins by adding capacity, as they always have. SanDisk is the fifth-largest player, subscale, a backup supplier at best. This is peak cycle. Sell the news.

The consensus may be wrong on three dimensions.

First, demand has changed character. When consumers chose between 16GB and 64GB iPhones, they made tradeoffs. When hyperscalers have stranded $20 billion in GPU investments, they do not negotiate on storage. Jensen designed SSDs into the compute fabric because there was no alternative. When storage becomes mandatory for AI to function , not nice-to-have but architecturally required , demand becomes inelastic. The buyer will pay market price because not buying means stranding billions in silicon.

Second, the supply response is broken. Leading-edge NAND fabrication facilities now cost $10 to $15 billion. Samsung and SK Hynix, who together control over half of NAND capacity, are diverting capital to High Bandwidth Memory. HBM earns hundreds of dollars per stack with desperate customers. NAND earns dollars per drive. The economics of building new NAND capacity, even at 65% gross margins, cannot compete with the economics of building HBM capacity. The NAND supply that will not be built in 2027 is the supply that would have broken the cycle.

Third, switching costs are rising. SSDs are being architected directly into custom silicon: NVIDIA’s Vera Rubin, Google’s TPUs, Amazon’s Trainium. Each architecture requires custom qualification , thermal testing, firmware integration, performance validation. This is not commodity plug-and-play. Once qualified, you do not swap suppliers mid-generation. SSDs are starting to behave like HBM itself: co-designed, qualified, sticky.

This creates an unusual dynamic. Hyperscalers learned from their dependence on NVIDIA for GPUs. They need four to five qualified NAND suppliers to maintain leverage. But so do the chip architects themselves. NVIDIA cannot be hostage to Samsung for a component now embedded in Vera Rubin. Google cannot depend on a single source for TPU storage. Amazon faces the same constraint with Trainium. Both the buyers and the architects of AI infrastructure need SanDisk to exist and to thrive.

The gap between street estimates and buyside whispers reveals the uncertainty. Published consensus shows roughly $32 in earnings per share for fiscal 2027. Fast money is modeling $80 to $100. Someone is dramatically wrong.

Three Futures

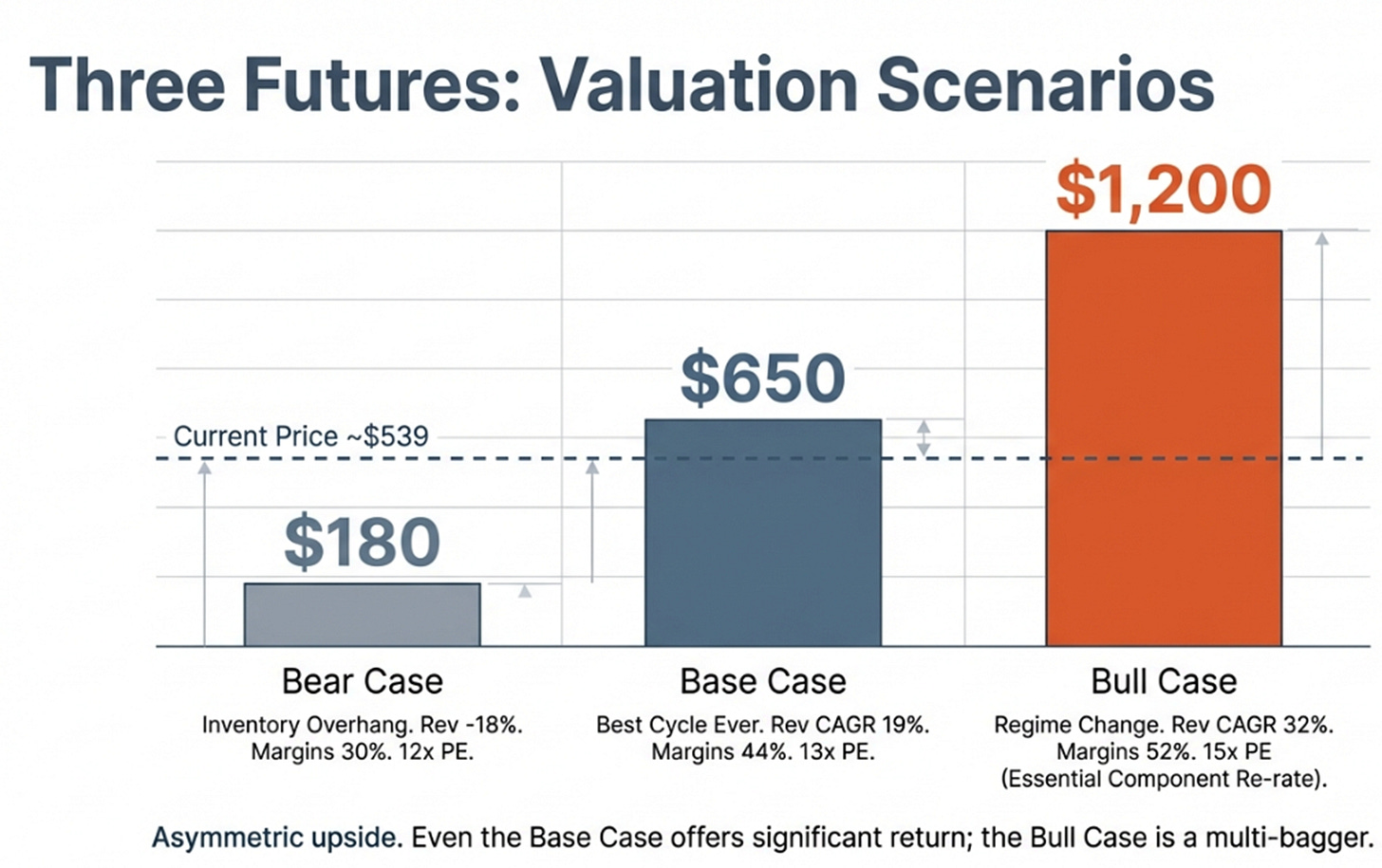

The Bull Case: $1,200

The regime change scenario. NAND becomes recognized as an essential AI component rather than a commodity.

Revenue grows from $15 billion to $35 billion over three years, a 32% compound annual growth rate driven by datacenter mix expanding to 40% of sales. Gross margins peak near 58% then settle at 52% as competition moderates but structural demand persists. Earnings reach $78 per share by fiscal 2029. The multiple re-rates from cyclical at 10-12x to essential component at 15x.

This requires Samsung to maintain HBM prioritization and never flood the NAND market. It requires SanDisk to achieve primary supplier status at three or more hyperscalers. It requires no architectural disruption from technologies like CXL memory pooling.

The Base Case: $650

The best cycle in NAND history, but still a cycle.

Revenue grows from $15 billion to $25.5 billion, a 19% compound annual growth rate. Gross margins peak at 54% then normalize to 44% as modest capacity additions restore competitive balance. Earnings reach $50 per share. The multiple remains in quality cyclical range at 13x.

This requires measured competitive response rather than aggressive capacity builds. It requires datacenter mix reaching 25-30% of revenue. It requires demand growth continuing through fiscal 2027 before moderating.

The Bear Case: $180

The music stops. Hyperscalers discover inventory overhang simultaneously.

Revenue stalls and contracts 18% in a fiscal 2028 trough as procurement offices realize they have stockpiled months of storage. Gross margins collapse to 30%. Samsung, seeing sustained high margins, announces capacity expansion in mid-2027. Earnings trough at $8 per share before partially recovering. The multiple compresses to 12x.

This requires hyperscaler language to shift from “expanding” and “deploying” to “optimizing” and “digesting.” It requires Samsung to choose market share over HBM opportunity cost.

Assigning 25% probability to bull, 50% to base, and 25% to bear yields an expected value of $670 against the current price of $539. Positive, but not compelling for the risk involved.

The Dashboard

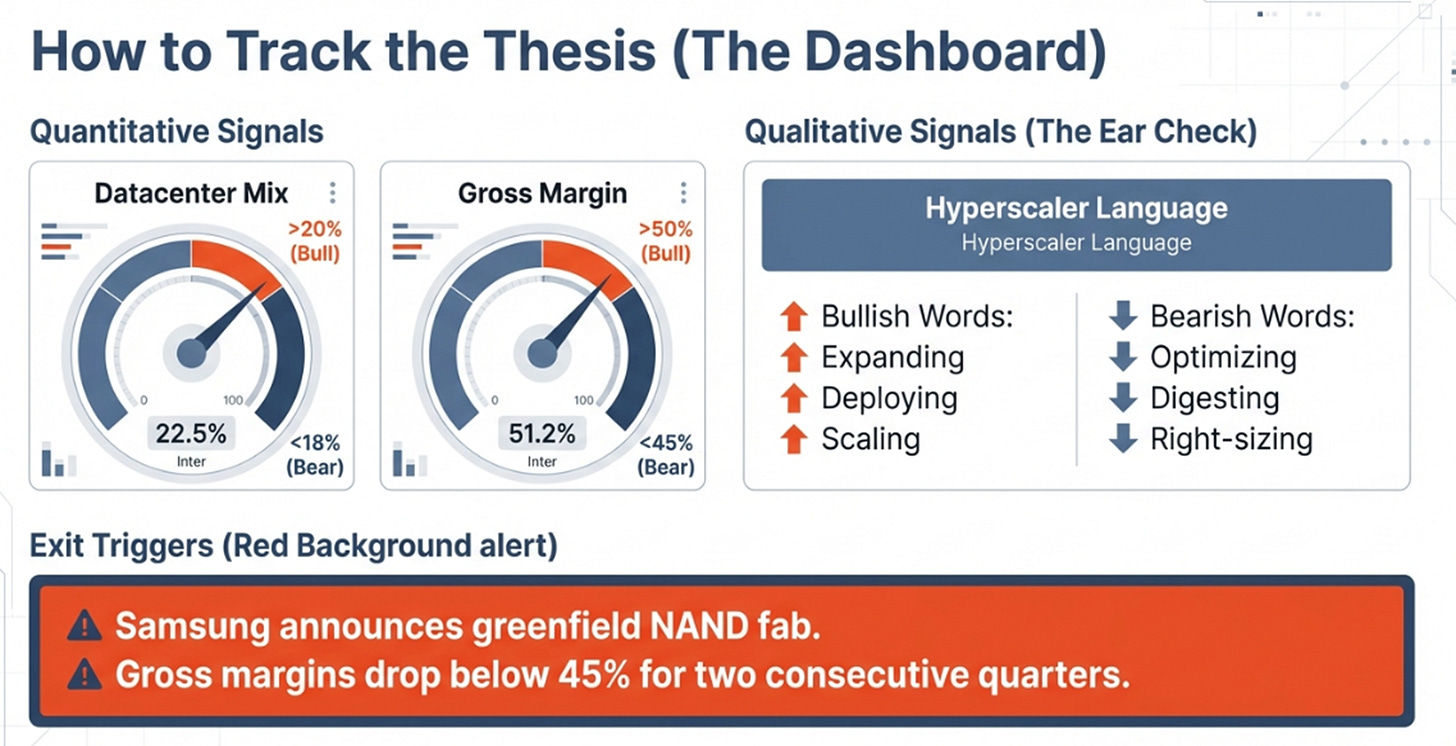

The quantitative signals to monitor quarterly: datacenter mix as a percentage of revenue, where above 20% and rising signals bull and stalling below 18% signals bear; gross margin, where sustaining above 50% signals bull and falling below 45% signals bear; inventory days, where above 135 warrants concern.

The qualitative signals matter more. Listen to hyperscaler earnings calls. “Expanding,” “deploying,” and “scaling” mean the buildout continues. “Optimizing,” “digesting,” and “right-sizing” mean procurement is about to dry up. Listen to SanDisk management. “Allocation” and “demand exceeds supply” mean pricing power. “Competitive” and “promotional” mean the cycle is turning.

The exit triggers: Samsung announces a greenfield NAND fabrication facility. Gross margins fall below 45% for two consecutive quarters. Any major hyperscaler uses “optimization” when discussing AI infrastructure spending.

The Toll Booth

On January 5th, Jensen Huang described a problem NVIDIA could not solve with chips alone. He needed storage inside the compute fabric. Three weeks later, the earnings proved the demand is real.

At $539, after a 1,400% run, the natural instinct is to assume the opportunity has passed. It has not , it has transformed.

Street estimates at $32 for fiscal 2027 are still sixty percent below where buyside models are landing. The architectural integration story , SSDs co-designed into custom silicon across NVIDIA, Google, and Amazon , is barely understood. The switching costs that come with qualification into Vera Rubin, into TPUs, into Trainium, are not priced as durable advantages. They should be.

A year ago, SanDisk was the fifth wheel in a commodity industry. Today, both the buyers and the architects of AI infrastructure need SanDisk to exist. That is not a cyclical dynamic. That is a moat forming in real time.

Jensen built the twenty-lane GPU highway. SanDisk is paving the on-ramps. He told us they are mandatory. The earnings proved the economics are extraordinary. The easy 10x is done. The next 2x may be harder, but the path is visible.

Disclaimer:

The content does not constitute any kind of investment or financial advice. Kindly reach out to your advisor for any investment-related advice. Please refer to the tab “Legal | Disclaimer” to read the complete disclaimer.

Brilliant framing of how SanDisk went from commodity player to infrastructure kingpin! The connection between Jensen's confession and the 65% gross margins really crystalizes why this isnt a typical NAND cycle. I've been watching hyperscaler capex closely and the inelastic demand argument makes total sence when storage becomes architecturaly embedded.