Sandisk: Between HBM and Hard Drives

How “warm storage” bridges the gap between ultra-expensive HBM and ultra-slow hard drives—and becomes a critical layer of the AI stack

TL;DR

GPUs can’t create value without fast, scalable access to petabyte-scale data—storage has become mandatory infrastructure.

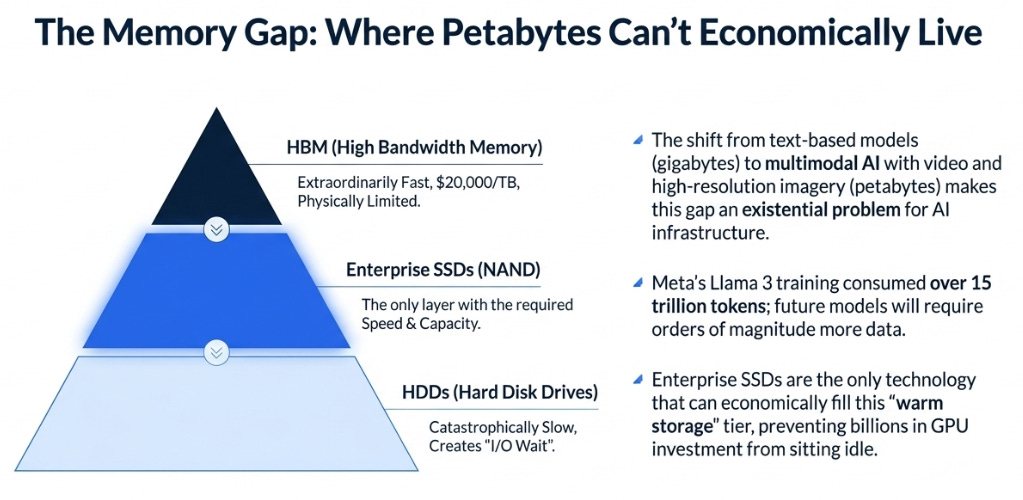

HBM is too expensive and limited; HDDs are too slow—only high-capacity enterprise SSDs economically fill the gap.

This “warm storage” layer turns NAND from a commodity into a structural bottleneck in AI deployment.

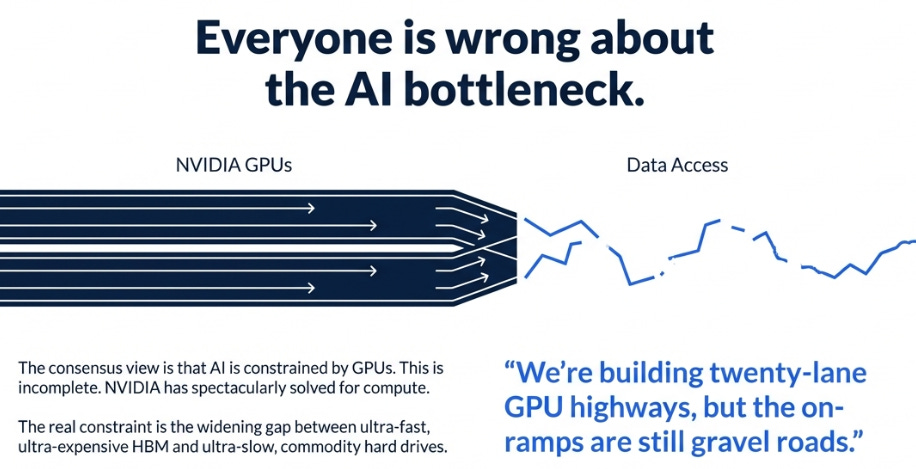

In 2024, Amazon invested roughly $75 billion in technology infrastructure largely for AWS and AI—and projects approximately $100 billion for 2025. Microsoft committed $80 billion to datacenter expansion. Meta is building compute equivalent to 600,000 H100s, including approximately 350,000 H100 GPUs. Every major tech company is building AI infrastructure at a scale that makes previous computing buildouts look quaint. But there’s a problem nobody wants to discuss: all this compute is increasingly worthless because the data can’t move fast enough.

The bottleneck isn’t the GPUs. NVIDIA solved that spectacularly. The bottleneck is memory—specifically, the gap between where AI models need data to be and where that data can economically exist.

Think of it this way: we’re building twenty-lane GPU highways, but the on-ramps are still gravel roads.

When Perfect Competition Destroys Value

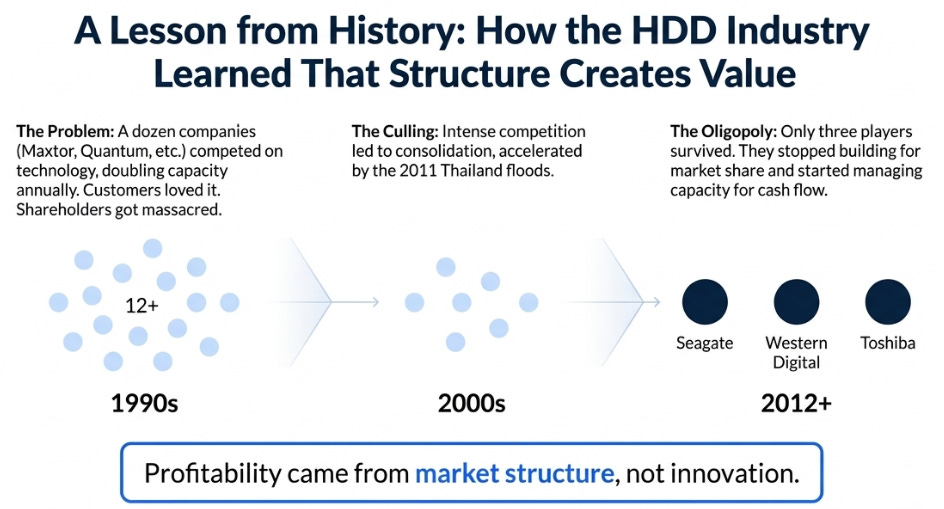

The hard disk drive industry learned this lesson the expensive way, and it’s worth understanding because NAND flash is following the exact same script, just twenty years behind.

In the 1990s, Maxtor, Quantum, Conner Peripherals, and a dozen others competed brilliantly on technology. They doubled capacity annually, shrunk form factors, improved reliability. Customers loved it. Shareholders got massacred. More than a dozen well-managed companies with genuine capabilities competed themselves into irrelevance.

The culling took longer than it should have. By 2005, five or six major players were still competing. But the 2011 Thailand floods and subsequent acquisitions—Seagate bought Samsung’s HDD business, WD bought Hitachi GST; finally forced consolidation. By 2012, only three survived: Seagate, Western Digital, Toshiba.

Here’s where it gets interesting. The survivors didn’t invent revolutionary technologies. They simply stopped building factories to capture share and started managing capacity for cash flow. Once only three players remained, each could see competitors’ moves in real-time. The prisoner’s dilemma gave way to rational restraint.

The lesson that took two decades to learn: profitability came from market structure, not innovation.

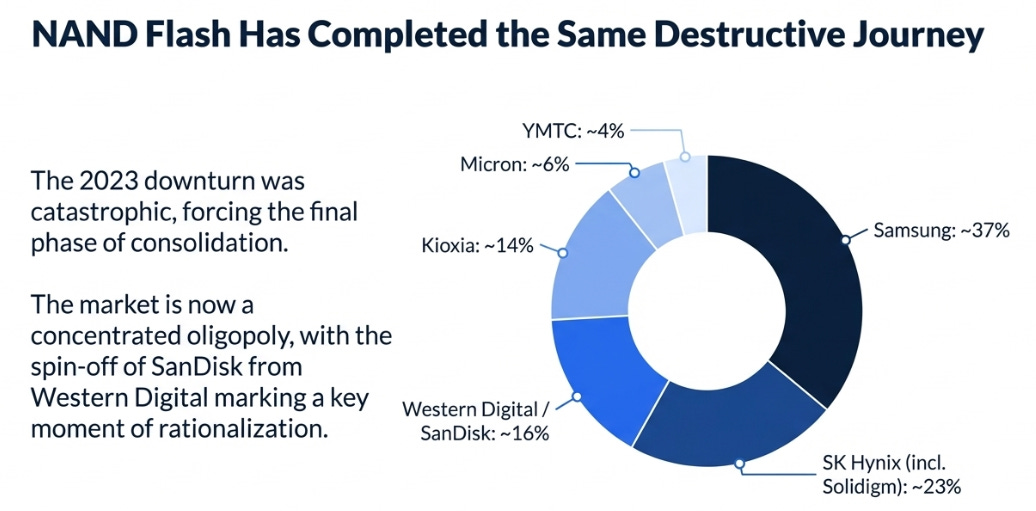

NAND flash just completed this journey. The 2023 downturn was catastrophic; pricing fell sharply, manufacturers reported billions in losses. A concentrated set of major suppliers emerged: Samsung controls approximately 37% of NAND revenue share, with SK Hynix (including Solidigm), Micron, Kioxia, Western Digital, and YMTC accounting for the remainder. When Western Digital split into two public companies in February 2025—WD retaining the HDD business while spinning off Flash under the SanDisk brand—it was joining an oligopoly that might finally choose discipline over destruction.

But here’s the critical question: does market structure matter if demand fundamentally changes character?

When Storage Stops Being Optional

Let’s pause here, because this is where the structural shift becomes visible.

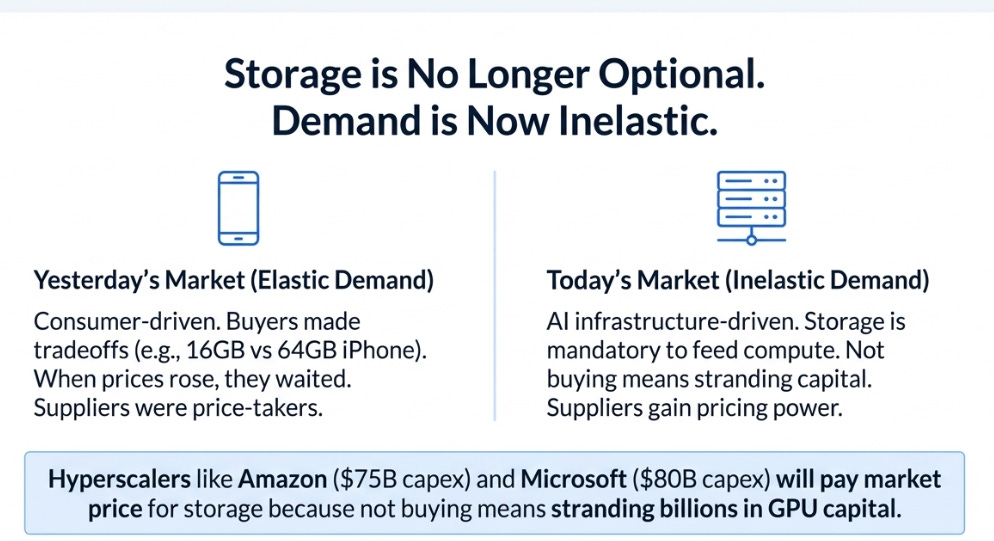

Historically, NAND demand was textbook elastic. When iPhones came in 16GB or 64GB versions, consumers made tradeoffs. When prices fell, they upgraded. When prices rose, they waited. This elasticity meant NAND suppliers were perpetual price-takers—no matter how good their technology, they couldn’t capture value.

AI breaks this dynamic, and the reason why reveals what makes this cycle different.

Meta spent roughly $20 billion building compute equivalent to 600,000 H100s. That compute is worthless without storage infrastructure to feed training data and serve inference results. The storage isn’t discretionary—it’s mandatory. Either it exists or the entire compute investment generates zero return.

But the memory hierarchy doesn’t work for AI. At the top sits High Bandwidth Memory: extraordinarily fast and extraordinarily expensive, with unit prices in the hundreds of dollars per stack and implied costs that make petabyte-scale storage economically absurd. HBM is physically limited by how many layers you can stack before thermal and electrical constraints dominate. At the bottom sit hard drives, several times cheaper per terabyte than enterprise SSDs but catastrophically slow. When GPUs process trillions of operations per second, waiting milliseconds for spinning disks creates “I/O wait.” Your expensive silicon sits idle.

The gap between HBM and HDDs used to be manageable when AI meant text models. But AI is shifting to multimodal workloads—video, high-resolution imagery, audio—and this matters more than most people realize. Industry analyses confirm that video and multimodal data create storage requirements orders of magnitude larger than text. Meta’s Llama 3 consumed over fifteen trillion tokens during training, and the shift toward video means data volumes that aren’t just larger, they’re fundamentally different in scale. These aren’t gigabyte problems, they’re petabyte problems. And petabytes can’t economically live in HBM.

What fills the gap is enterprise SSDs: ultra-high-capacity NAND drives that deliver gigabytes per second throughput with microsecond latencies. Studies show that shifting AI training checkpoints and active datasets from HDD to SSD meaningfully reduces training stalls and improves GPU utilization. This “warm storage” tier isn’t optional. It’s the only technology that delivers both the capacity and speed AI requires.

Here’s the structural shift: when demand becomes inelastic, pricing power transfers from buyer to seller. The hyperscaler will pay market price because not buying means stranding billions in GPU capital.

Suddenly, NAND isn’t a commodity, it’s the chokepoint.

The twenty-lane highway is built. Now the question is who controls the on-ramps.

The Fragility Nobody Discusses

Before explaining why SanDisk’s position works, let’s acknowledge why it’s fragile. This matters because the bull case only works if you understand the risks.

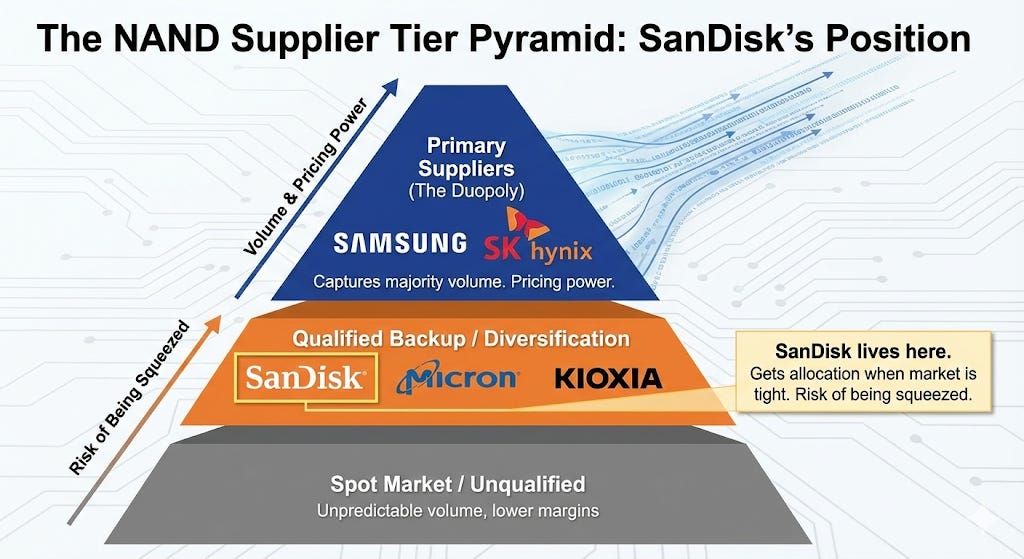

SanDisk holds roughly 10-11% of global NAND market share by revenue. Samsung leads with approximately 37%, followed by SK Hynix/Solidigm, Kioxia, and Micron. Being valuable as insurance doesn’t guarantee capturing that value through sustainable margins. Hyperscalers excel at maintaining competitive tension even while managing strategic relationships.

Here’s what the procurement dynamics likely look like—and it’s important to note this is analytical inference rather than disclosed fact: SanDisk probably qualifies as approved vendor at multiple hyperscalers but occupies backup tier for most. In typical enterprise procurement patterns, customers maintain two primary suppliers capturing the majority of volume, with additional qualified backups splitting the residual. If this pattern holds for NAND, SanDisk gets backup allocation—valuable during tight markets, but temporary. When supply loosens, volume shifts back to Samsung and SK Hynix.

The enterprise mix shift management emphasizes—from low single-digit datacenter historically to 12% currently per recent reports, targeting substantially higher longer-term—requires competing for primary supplier status. Samsung spent fifteen years building these relationships. SanDisk is compressing the timeline into 3-4 years.

If datacenter revenue stalls at mid-teens percentage of mix, we’re looking at backup supplier status—and margins that can’t hold.

The joint venture with Kioxia adds another layer of uncertainty. Kioxia and Western Digital have attempted to merge their operations multiple times, but deals have been blocked—notably by SK Hynix, an indirect Kioxia investor. This fragility isn’t purely financial; it’s political and legal, adding risk to the partnership structure that provides SanDisk’s manufacturing scale.

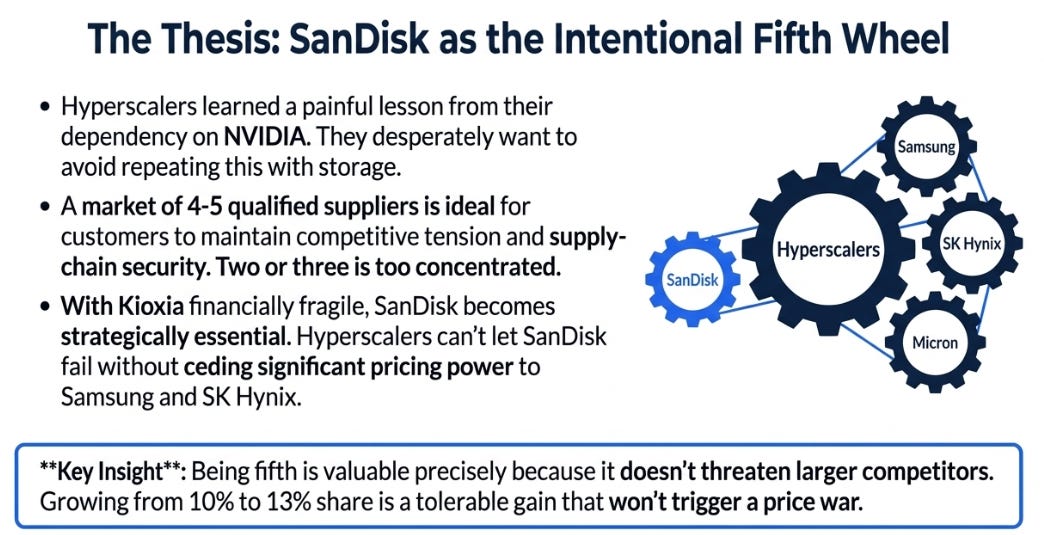

That acknowledged, here’s where it gets weird: being fifth actually keeps everyone else honest.

The Intentional Fifth Wheel

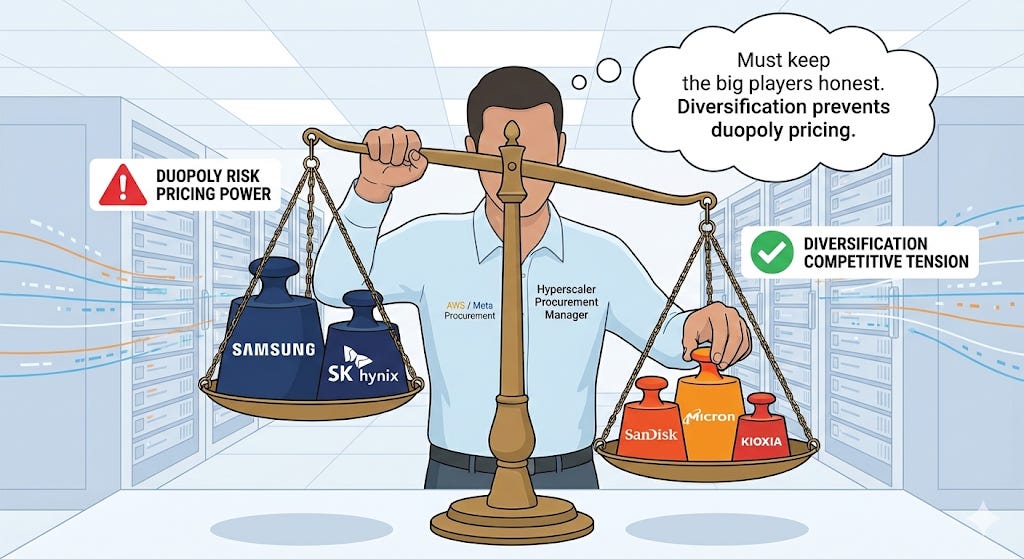

Start from the hyperscaler perspective. They learned painful lessons from GPUs. When one supplier controls the majority of critical input—as NVIDIA does with accelerators—that supplier captures economics. Customers have minimal leverage and risk strategic dependency.

Hyperscalers desperately want to avoid repeating this with storage. The ideal structure appears to be 4-5 qualified suppliers based on how cloud providers discuss vendor diversification and supply-chain risk. Two creates duopoly pricing. Three is better but concentrated. Four to five enables genuine competition—customers can dual-source while maintaining alternatives.

But Kioxia, while technologically capable, remains financially fragile with repeatedly delayed IPO plans. If Kioxia exits, the market compresses to fewer players.

This is where SanDisk becomes strategically valuable—and here we’re moving from observed facts to strategic hypothesis: hyperscalers likely can’t let SanDisk fail without ceding pricing power to Samsung and SK Hynix. This doesn’t mean SanDisk can price arbitrarily—it means SanDisk gets qualified, receives allocation during tight markets, and potentially captures premiums for being the diversification option.

The counterintuitive part is this: being fifth is valuable precisely because it doesn’t threaten larger competitors. If SanDisk tried capturing 15% share, it would trigger defensive responses—Samsung would deploy capital to protect position, potentially flooding the market. But growing from 10-11% to 13% represents marginal gains larger players can tolerate.

The capital structure amplifies this advantage. SanDisk’s joint venture with Kioxia shares R&D and manufacturing costs. Leading-edge NAND fabs require multi-billion-dollar investments. Kioxia shoulders half this burden while SanDisk monetizes output in Western markets. Samsung justifies massive investments through scale. SanDisk accesses equivalent capability at half the capital.

This creates fast-follower economics as strategic advantage. Samsung ramps advanced V-NAND, absorbing yield risks and development costs. SanDisk’s BiCS8 sits at 218 layers—behind Samsung’s latest generation. In consumer electronics, this lag would be fatal. But enterprise AI customers optimize for capacity, endurance, and qualification status, not bleeding-edge density.

A hyperscaler deploying 256TB drives cares whether suppliers can deliver committed volumes with predictable quality, not whether underlying NAND uses 218 layers or Samsung’s latest generation count. SanDisk manufactures products using mature, high-yielding processes while Samsung pioneers next-generation nodes. When Samsung’s latest process eventually matures, SanDisk will be ramping 332-layer BiCS10 using lessons Samsung paid to learn.

And here’s the subtle part: if hyperscalers actively value SanDisk for supply diversity, which procurement behavior suggests they might—they would support its capacity through allocation even during soft markets. This means Samsung’s incremental capacity competes not just with SK Hynix and Micron, but with a SanDisk that customers want to preserve. The fifth player raises the bar for rational capacity additions.

The question isn’t whether being fifth is viable—industry data shows it clearly is. The question is whether the favorable conditions that make it viable will persist long enough to matter.

Has Capital Intensity Broken the Cycle?

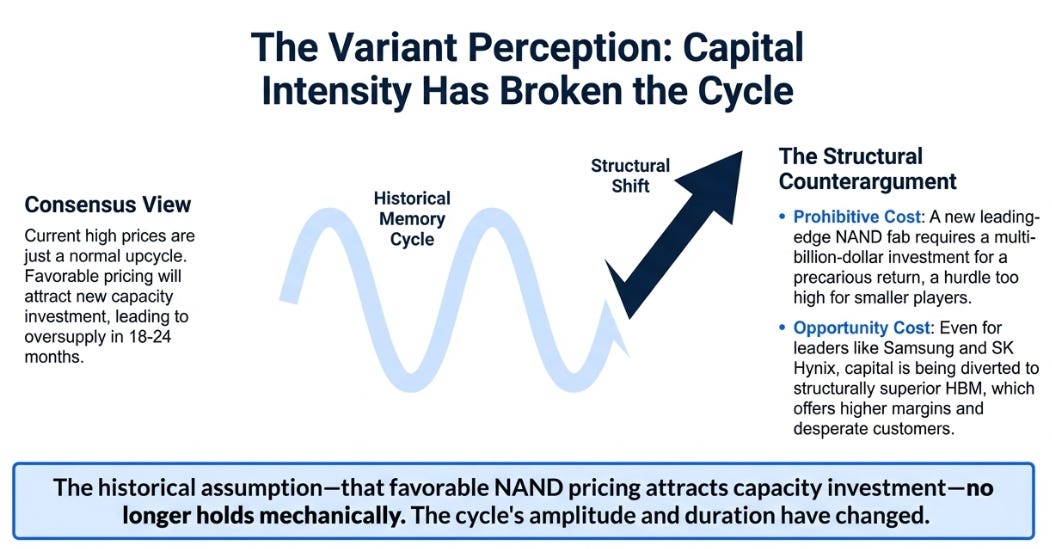

Here’s the variant perception in one sentence: the cost of adding supply now exceeds competitive returns.

The consensus treats current NAND pricing as typical cycle behavior—oversupply created losses, manufacturers cut capacity, supply tightened, pricing recovered. This script predicts favorable pricing attracts capacity investment, new fabs ramp in 18-24 months, and oversupply returns.

The structural counterargument is that the economics have fundamentally shifted.

Leading-edge 3D NAND fabs require multi-billion-dollar investments in land, building, equipment, and process development. As manufacturers push from 200 to 300 to eventually 1,000 layers, equipment becomes more expensive, yields more sensitive, returns more precarious.

Samsung can justify these investments because spreading massive capital across 37% global share generates cost-per-bit advantages. But for smaller players, the math has changed dramatically. Building a greenfield fab to capture 2 percentage points of share means billions in capital to generate perhaps $2 billion in annual revenue at peak utilization. Even assuming 40% gross margins, that’s $800 million in gross profit—a forty-year payback ignoring depreciation and the risk that the next cycle destroys profitability.

The return hurdle has become insurmountable except for the largest players. And even Samsung faces opportunity costs. Samsung and SK Hynix collectively control over half of NAND capacity, but both are diverting massive capital to High Bandwidth Memory. HBM unit prices are in the hundreds of dollars per stack with tight supply projected through 2025 and beyond, offering structurally superior economics: higher margins, faster growth, desperate customers.

This matters because it means the historical assumption—that favorable NAND pricing attracts capacity investment—no longer holds mechanically. If Samsung deploys billions toward HBM rather than NAND, that’s billions in NAND capacity that doesn’t materialize in 2027.

Let’s be clear about what this means: it doesn’t eliminate cyclicality. It raises the threshold for triggering new supply. The amplitude and duration change. The cycle doesn’t disappear.

Three Futures

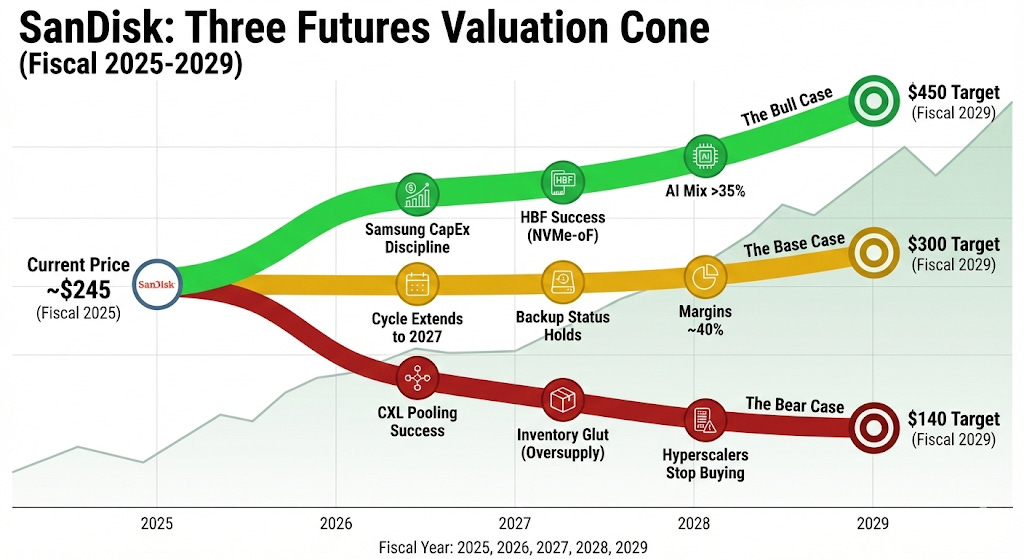

Current price of $244.50 embeds specific assumptions. What follows are illustrative scenarios—investor modeling, not predictions—designed to make those assumptions explicit and testable.

What if this is real? → $450 scenario

In this construction, AWS makes SanDisk a primary supplier for 30% of its new clusters by fiscal 2027. Microsoft and Google follow. Enterprise datacenter grows from roughly 12% of revenue today to 35% of mix. High Bandwidth Flash launches successfully—enabled by NVMe over Fabrics adoption allowing high-speed NAND to actually feed GPU clusters efficiently—and by late 2027 NVIDIA and AMD have designed around it. Samsung and SK Hynix maintain capital discipline because HBM returns exceed NAND by wide margins.

Revenue grows 25% annually to $16.5B by fiscal 2029. Gross margins sustain at 45-48%. Operating margins reach 30%, generating $25 EPS. The market re-rates from cyclical to AI infrastructure, applying 18× multiple for $450 target.

What breaks it: Samsung announces greenfield NAND fab in 2026. HBF fails customer traction—the ecosystem bet on fabric layer architecture doesn’t materialize. Enterprise mix stalls below 20% because SanDisk remains backup supplier.

What if it’s just a better cycle? → $300 scenario

In this construction, SanDisk qualifies at four hyperscalers but captures primary status at only one. Enterprise reaches 20-22% of mix—meaningful but not transformative. One hyperscaler qualification converts to substantial annual contract value. The others provide backup allocation during tight markets.

Revenue grows 15-18% annually to $13.5-14.5B. Gross margins peak at 43-45% in fiscal 2026-27 then normalize to 38-40% as startup costs disappear but competitive pricing moderates. One downturn occurs in fiscal 2028-29, but the trough is higher because AI infrastructure creates demand floor. Through-cycle returns improve meaningfully versus historical.

Operating margins settle at 20-22%, generating $18 EPS. Stock trades at 14-16× for $280-320 target.

What validates it: Samsung adds modest capacity but doesn’t flood market. Enterprise mix reaches 20-22% with sustained margins above 40%. The cycle extends through 2027 before moderating, giving SanDisk time to build competitive moats.

What if we’re being played? → $140 scenario

In this construction, the hyperscalers are playing musical chairs right now—everyone’s grabbing seats. But when the music stops in 2027—when next-generation models underwhelm, when inference computational requirements don’t scale as expected, when someone realizes they’ve collectively stockpiled months of inventory—they’ll all stop buying at once.

There’s another risk the market isn’t pricing: Compute Express Link (CXL) technology enabling memory pooling and disaggregation is progressing faster than anticipated. Research prototypes demonstrate near-local DRAM latency through CXL-based memory pools. If CXL 3.0 enables memory pooling at scale by 2027, hyperscalers could satisfy AI workloads with meaningfully less NAND capacity than current architectures require. This architectural shift could reduce—though not eliminate—the “missing middle” requirement.

Here’s what happens: AWS reviews deployment schedules in Q2 2027 and realizes it has months of SSD inventory relative to buildout pace. Microsoft does the same analysis. Google follows. By mid-2027, procurement orders have fallen sharply across all suppliers. Samsung, defending share, cuts pricing to maintain utilization. The industry returns to oversupply faster than anyone expected.

Revenue grows just 5-8% to $10-11B by fiscal 2029—below fiscal 2026 after the cycle peak. Gross margins compress to 25-30%. Operating margins fall to 10-12%, generating $9 EPS. The market re-rates as distressed cyclical at 10-11× for $140 target.

The warning signal isn’t financial results—it’s language. When Microsoft or Amazon discuss “right-sizing storage” or “optimization” rather than “expanding capacity,” procurement is about to dry up. Investors who wait for SanDisk’s earnings to reflect weakness will be too late.

What to Watch

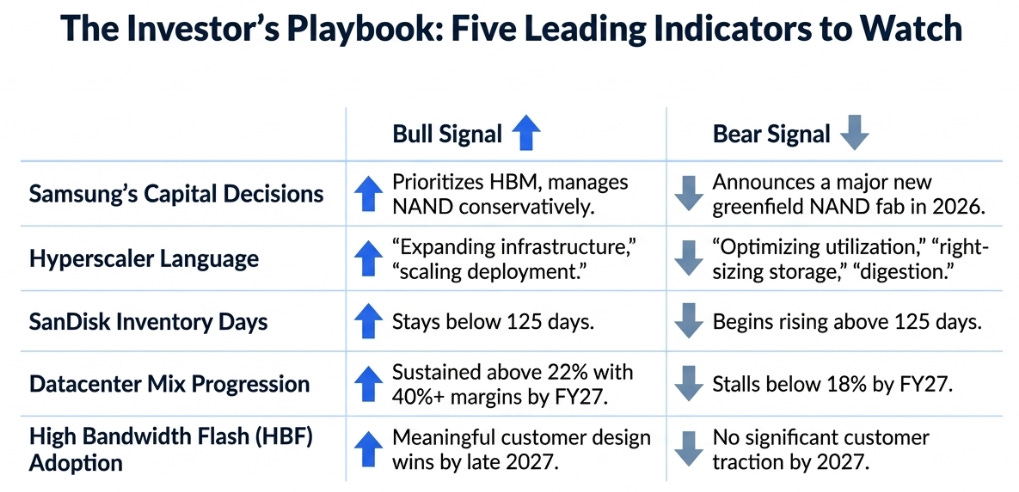

Five leading indicators matter more than quarterly financials:

Samsung’s capital decisions. Ignore rhetoric, watch greenfield fab construction. If Samsung announces major new NAND facility during 2026 while pricing remains elevated, competitive dynamics haven’t changed—oversupply returns in 2027-28. If Samsung prioritizes HBM while managing NAND conservatively, it validates structural discipline.

Hyperscaler language. Track the exact phrasing in quarterly calls and capital allocation discussions. “Expanding infrastructure” and “scaling deployment” indicate continued buildout. Warning signals: “optimizing utilization,” “right-sizing storage,” or “digestion.” These indicate transition from deployment to efficiency mode.

SanDisk inventory days. Improved from 150 to 135 to 115 days per available reports. If inventory begins rising—particularly above 125—demand is softening relative to production. This leads revenue and margin pressure by 1-2 quarters.

Datacenter mix progression. Quarterly disclosure of enterprise and datacenter revenue as percentage of total provides the clearest signal of whether SanDisk is transitioning from backup to primary supplier status. Below 18% by fiscal 2027 suggests backup positioning with temporary margin boost. Above 22% with margins sustained above 40% validates successful transition.

High Bandwidth Flash adoption. Customer design wins by late 2027 would create meaningful incremental revenue by 2029, materially changing the valuation framework. No customer traction by 2027 means interesting technology with minimal financial impact.

Structure Over Silicon

The opportunity extends 12-18 months with high confidence based on disclosed guidance and observable industry conditions. Management guides 41-43% gross margins, hyperscalers are deploying over $400B combined in AI infrastructure, industry supply remains constrained. At $244, roughly 19× fiscal 2026 earnings estimates, this offers reasonable risk-reward for near-term participation. A pullback to $210-225 would provide better entry with 30-40% upside to base case scenarios.

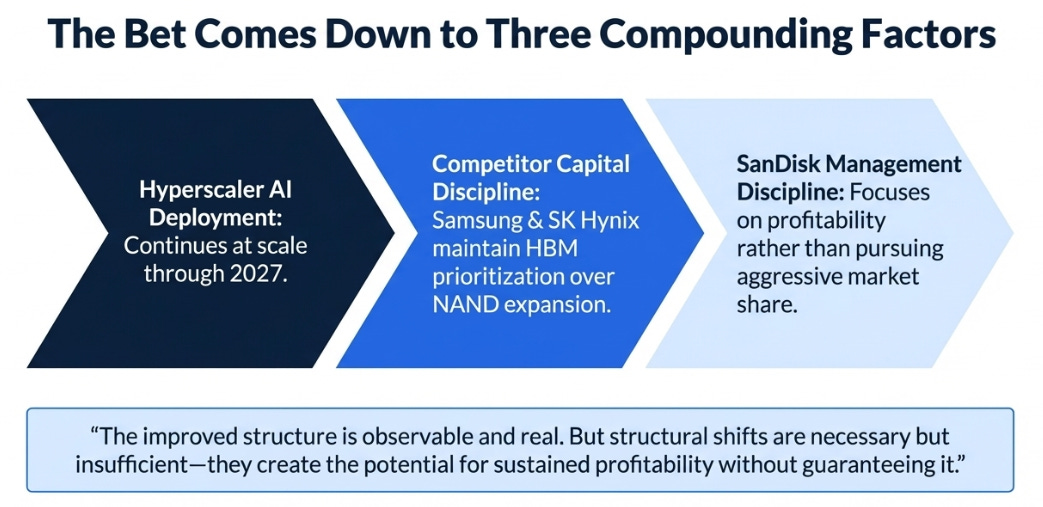

But beyond 18 months, conviction requires distinguishing between probable and possible. The structural argument is intellectually compelling: consolidation to a concentrated set of suppliers, capital intensity exceeding competitive returns for all but the largest players, AI creating more inelastic demand characteristics than historical NAND applications. These factors could permanently alter NAND economics. The improved structure is observable and real.

Yet capital-intensive oligopolies have long histories of discipline breaking precisely when it’s most valuable. HDDs reconsolidated to effectively two primary players by 2012, yet even that duopoly hasn’t generated spectacular returns. DRAM experienced similar consolidation but still suffers brutal cycles. Structure improvement is necessary but insufficient—it creates potential for sustained profitability without guaranteeing it.

The bet on SanDisk comes down to three compounding factors: continued hyperscaler AI deployment through 2027, Samsung and SK Hynix maintaining HBM prioritization over NAND capacity expansion, and SanDisk management maintaining capital discipline rather than pursuing market share through aggressive investment. If all three prove true, the bull scenario becomes plausible. If two hold, base case delivers acceptable returns. If one or zero, bear case becomes reality.

The HDD parallel teaches the final lesson: profitability in capital-intensive industries comes from market structure, not technological superiority. The moat isn’t better chips—it’s the cost of competition exceeding competitive incentives.

NAND’s moment arrives if the cost of adding supply has finally exceeded the reward for share gains. This represents a real structural shift supported by observable changes in capital requirements and competitive dynamics. But structural shifts in demand don’t eliminate cyclicality if supply can respond. The challenge is recognizing the window is time-bound.

Buy the cycle while discipline holds. Prepare the exit before consensus recognizes when discipline breaks. In memory investing, generating returns requires understanding that maximum opportunity coincides precisely with when everyone must start planning their departure.

The GPU highway is twenty lanes wide and filling up fast. SanDisk wants to be the company that finally paves the on-ramps. The problem is, everyone else is watching to see if the traffic might just build its own exit instead.

Disclaimer:

The content does not constitute any kind of investment or financial advice. Kindly reach out to your advisor for any investment-related advice. Please refer to the tab “Legal | Disclaimer” to read the complete disclaimer.