SMIC: The Great Wall of Silicon

What Huawei’s 7nm Kirin 9000S tells us about SMIC’s true purpose.

TL;DR

SMIC isn’t a business, it’s infrastructure. Like Project 596 and China’s high-speed rail, its value lies in existence, not profitability.

Financials are a managed illusion. Capex exceeding revenue, margins capped around 20%, and state-directed demand show a geopolitical mission disguised as a P&L.

The goal is survival, not dominance. By holding the line at 7nm and investing in packaging, SMIC ensures China’s technological sovereignty—even if investors never see returns.

In October 1964, China detonated its first atomic bomb in the Xinjiang desert. The project, code-named “596” after the June 1959 date when Soviet assistance was withdrawn, consumed an estimated 1% of China’s GDP throughout the early 1960s. By any commercial metric, it was insane: a country where people were starving spent billions developing weapons it hoped never to use.

But China’s leaders weren’t measuring return on investment. They were buying insurance against nuclear blackmail. The bomb’s value wasn’t in its deployment but in its existence.

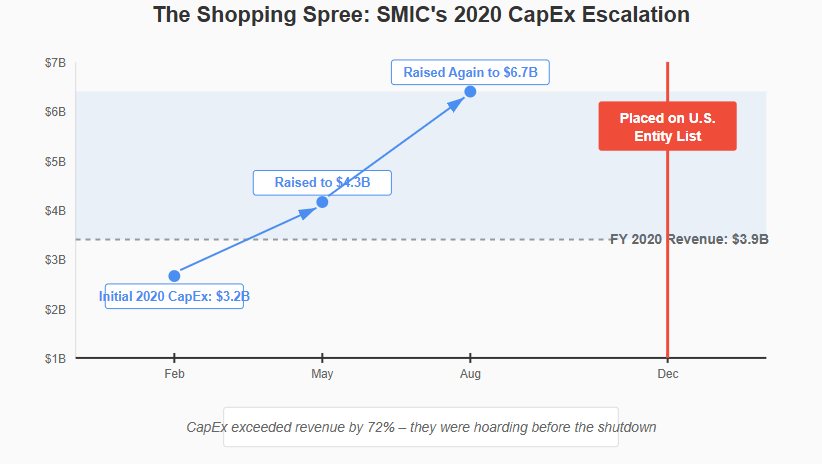

I thought of Project 596 while reading Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation’s (SMIC) 2020 annual report. In a single year, SMIC raised its capital expenditure guidance three times: from $3.2 billion to $4.3 billion in Q1, then to $6.7 billion in Q2. For context, the company’s total revenue that year was $3.9 billion.

No rational business invests 170% of revenue in capital equipment. Unless, of course, it’s not really a business at all.

The Shopping Spree

The capex raises tell a story hiding in plain sight. In January 2020, SMIC was a normal foundry, competing globally, raising capital expenditure by a reasonable 35% to support growth. By May, something had changed. Management doubled down, raising capex to levels that would consume all cash flow and require massive new funding.

What changed wasn’t in the market—demand was strong, prices were rising. What changed was what management could see coming. The U.S. had placed Huawei on the Entity List in May 2019. The direction was clear: more restrictions were coming, and eventually they would hit SMIC directly.

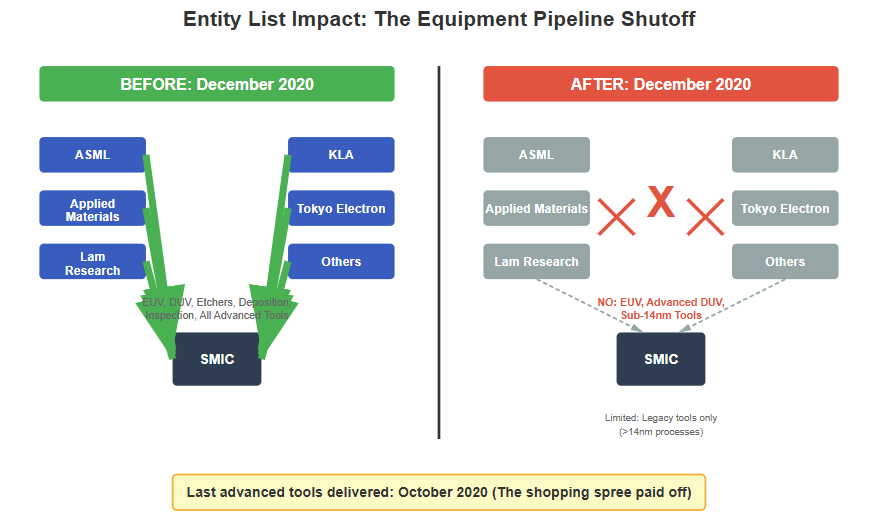

That summer’s spending spree wasn’t expansion. It was hoarding. SMIC bought every piece of advanced equipment it could, knowing the store was about to close. Those tools ordered in summer 2020 would be the last advanced equipment SMIC would ever receive. In December 2020, the hurricane hit: the U.S. Department of Commerce added SMIC to the Entity List.

Management had seen it coming. But even they couldn’t have predicted what would happen next.

The Letter

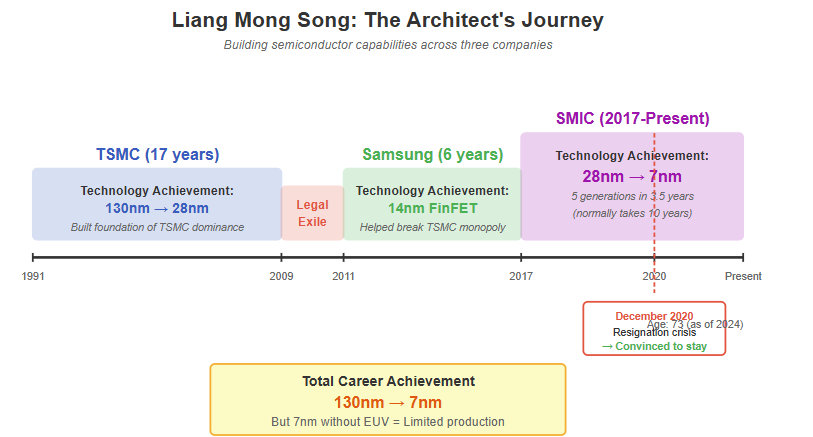

Five days after the Entity List designation, Liang Mong Song sat down to write his resignation. The 69-year-old engineer had spent seventeen years at TSMC building their technology from 130nm to 28nm, then been exiled after a bitter lawsuit, served time at Samsung, and finally found redemption at SMIC. His letter should have remained confidential. Instead, it leaked—sending SMIC’s stock down 10% in hours.

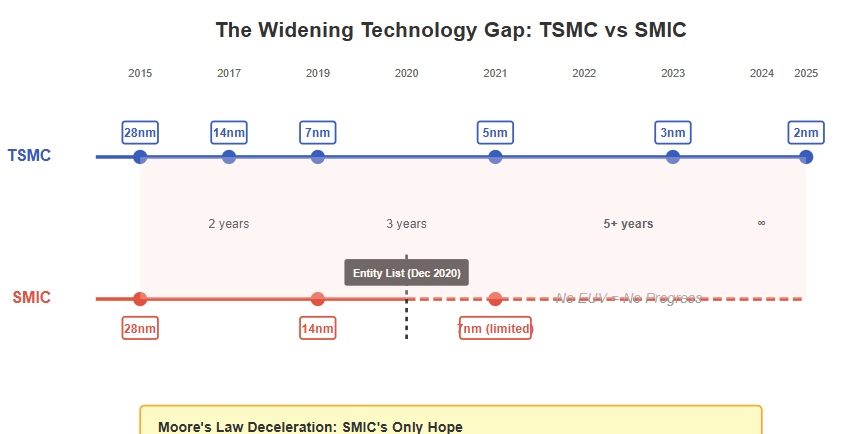

“During my three and a half years at SMIC,” Liang wrote, “I have helped the company complete development from 28nm to 7nm, a total of five technology generations. This is an achievement that would normally take ten years.”

Buried in his bitterness about board politics was a revelation: SMIC had achieved 7nm technology. Not production, not commercialization, but the technical capability. At the exact moment when sanctions made it impossible to manufacture at scale, SMIC had proven it could match technology from just two generations behind the global leaders.

The board scrambled to keep Liang, offering apologies and assurances. He stayed, but the damage was done—not to SMIC’s stock price, which recovered, but to any pretense about what SMIC really was. Liang had built something extraordinary that could never fulfill its commercial potential. His letter was both a resignation and a confession: he was building monuments, not products.

The Revelation

Here’s what took me too long to understand: SMIC is not a semiconductor company. It is a geopolitical entity with a P&L statement.

Once you accept this, everything makes sense. The impossible capital expenditure ratios—what kind of business spends more on equipment than it generates in revenue? The kind that isn’t really a business. The margin structure that hovers around 20%, occasionally spiking to 30% during shortages, occasionally dropping to 15% during downturns—this isn’t market dynamics. It’s an engineered equilibrium, high enough to maintain stock exchange listings, low enough to justify continued subsidies.

When margins drop too low, a convenient order from a state-owned enterprise appears. When they rise too high, capacity expansions accelerate. The company’s reported profitability is a carefully managed variable, designed to be just good enough to sustain the fiction of a commercial enterprise.

Think of China’s high-speed rail network, which operates at massive losses. Its value isn’t in ticket sales but in economic integration. SMIC’s fabs are the same: their return isn’t measured in wafer revenue but in technological sovereignty. No commercial entity approves capital expenditure equal to revenue year after year. But infrastructure projects do this routinely.

This framework explains everything, including the most puzzling event of 2023.

The Message

When Huawei’s Mate 60 Pro appeared in August 2023 with a 7nm chip manufactured by SMIC, Western analysts scrambled to understand. How had SMIC achieved 7nm production without EUV lithography? What did this mean for the effectiveness of sanctions?

They were asking the wrong questions. The Kirin 9000S wasn’t really a product launch; it was a message. Like China’s first atomic bomb, its value wasn’t in its performance—the yields were reportedly below 50%, the cost per chip astronomical—but in its existence. The medium was the message: we can build what you thought we couldn’t.

Management barely discussed it on earnings calls. They didn’t need to. Everyone understood what it meant. Discussing it as a commercial product would invite scrutiny of its terrible economics. Discussing it as a strategic project would confirm its role in subverting U.S. policy, inviting even harsher sanctions. They were trapped by their own success.

But success in what? Not in building a profitable semiconductor company—that was never the goal. Success in proving that technological sovereignty was possible, even at extraordinary cost.

The New Math

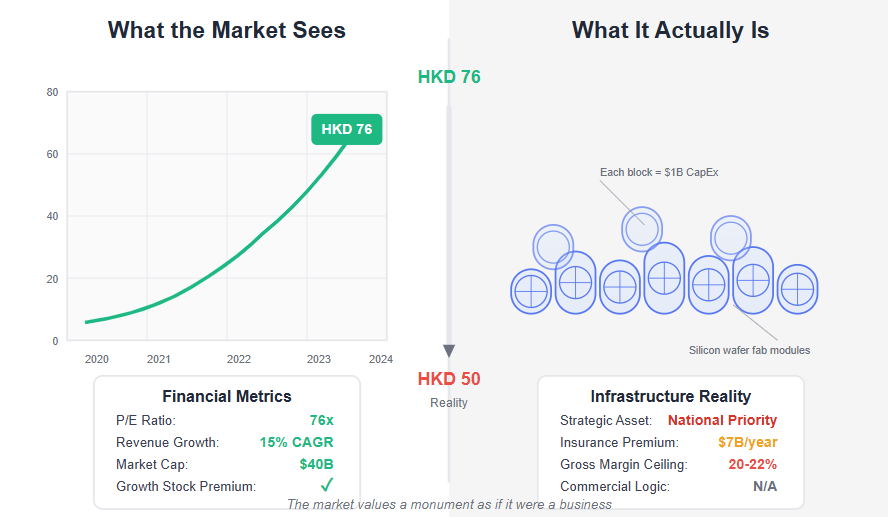

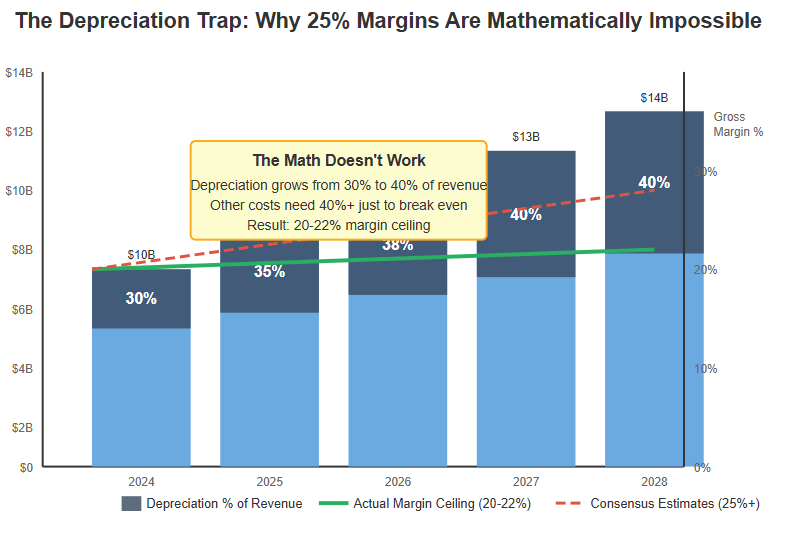

This changes how we should read SMIC’s financials entirely. Analysts puzzle over the depreciation trap: SMIC adds $7 billion in equipment annually, creating $4-5 billion in depreciation charges. On a $12 billion revenue base, that’s 33-40% of sales before any other costs. Gross margins are mathematically capped around 20%.

But this isn’t a bug; it’s a feature. Infrastructure doesn’t need 40% gross margins. It needs to exist.

The consensus expects margins to expand to 25% by 2027 as fabs scale. They’re analyzing the wrong entity. They might as well expect the subway to become profitable. SMIC’s job isn’t to generate returns; it’s to ensure China’s electronics industry can’t be strangled by foreign powers.

Even the competitive dynamics make sense through this lens. Western analysts fear Chinese foundry oversupply, imagining brutal price wars as two dozen new fabs come online. But why would the state, as primary funder of SMIC, Hua Hong, and every other Chinese foundry, allow its strategic assets to engage in mutually destructive competition?

More likely, we’ll see managed competition—SMIC as the flagship, others as specialized support vessels, each with assigned roles in the fleet. The state will direct funding and contracts to maintain this balance. They’re not competing against each other for survival; they’re collectively competing against foreign dependency.

The War of Attrition

Understanding SMIC’s true nature reveals its actual strategy. They’re not trying to catch TSMC at 3nm. They know they can’t win that race without EUV lithography. Instead, they’re fighting a war of attrition, trying to maintain technological relevance while physics does their work for them.

Moore’s Law is slowing. The jump from 7nm to 5nm delivers less benefit than from 14nm to 10nm. Each generation takes longer, costs more, and yields smaller improvements. SMIC doesn’t need to catch up; it needs to stay close enough while exploring alternative paths—chiplets, advanced packaging, novel architectures.

Time, paradoxically, is on SMIC’s side. Not in catching up, but in making the gap matter less. If they can hold the line at 7nm while developing sophisticated packaging technologies, they might achieve “good enough” performance for China’s needs. Not optimal, but survivable.

This is a very different game than the one TSMC is playing. TSMC optimizes for excellence. SMIC optimizes for existence.

Three Futures

Let me paint three scenarios for SMIC by 2027, each flowing from this understanding:

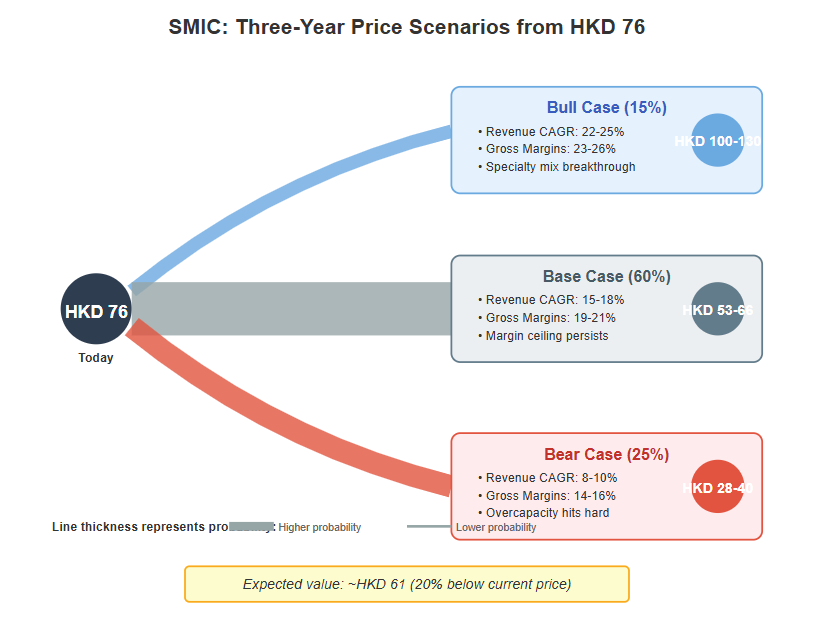

In the most likely future—call it The Eternal Grind with 60% probability—SMIC continues exactly as it is. Revenue grows at 15-18% annually as state-directed volume fills fabs. Gross margins stay trapped between 19-21%, that carefully engineered band that keeps the company viable but not threateningly profitable. By 2027, earnings per share reach about $0.17 USD, but the market finally understands what it’s valuing. The multiple compresses from today’s 76x to perhaps 30-35x—still high for a utility, but reflecting China’s strategic premium. The stock reprices to HKD 53-66.

There’s a chance—maybe 15%—of temporary escape. If automotive and specialty products explode faster than expected, if SMIC’s 28nm AMOLED display drivers and RF-SOI products capture significant share, mix could improve faster than depreciation weighs. Margins might reach 23-26%, earnings could hit $0.28-0.31 USD. The market might maintain hope, keeping multiples around 35-40x. In this Brief Escape scenario, the stock reaches HKD 100-130. But even here, SMIC only postpones its infrastructure destiny, not avoids it.

The darker possibility—25% probability—is that even infrastructure can fail if overbuilt. China’s 25+ new fabs could create such severe oversupply that SMIC faces utilization below 70% and margins below even the state’s tolerance. With earnings crashing to $0.07 USD and multiples compressing to distressed levels around 20-25x, the stock could fall to HKD 28-40. This Reckoning would trigger either forced consolidation or even more aggressive state support.

The Signal and the Noise

Tracking SMIC requires watching different signals than a normal semiconductor company. Revenue forecasts matter less than ASP trends by node—commoditization speed tells you if oversupply is arriving. Utilization below 75% signals danger. The ratio of gross margin to depreciation reveals whether the ceiling is holding.

Most important is the human element. Liang Mong Song embodies SMIC’s technical capability. At nearly 74, his health is material information. When he finally leaves, SMIC loses not just an engineer but the bridge to its aspirational past when it still dreamed of catching TSMC.

But perhaps that’s fitting. Because SMIC’s future isn’t about catching anyone. It’s about something more profound and less profitable: ensuring China’s technological survival.

The Price of Everything

The Huawei Kirin 9000S chip perfectly encapsulates SMIC’s paradox. Its existence proved Chinese semiconductor capability had survived sanctions. It also guaranteed those sanctions would tighten further. Success in the mission ensures failure in the market.

At HKD 76, SMIC trades at a forward P/E ratio that would make a software company blush. The market is pricing it like a growth technology stock. But growth technology stocks can raise prices, improve margins, and generate returns. Infrastructure can only fulfill its purpose.

The question isn’t whether SMIC will succeed—it already has. It exists, it manufactures chips China needs, and it will continue to exist regardless of financial returns. The question is when markets will recognize they’re not valuing a company but a component of national infrastructure.

Project 596 succeeded in building China’s nuclear deterrent. It never generated a penny of profit, but that was never the point. SMIC is Project 596 for the semiconductor age—strategically essential, commercially irrelevant.

At current prices, investors are confusing the two. They’re buying shares in a monument, expecting returns from a business. The monument will endure. The returns will not.

Ultimately, Investing in SMIC is not a bet on a semiconductor company. It is a direct, leveraged bet on the political will and technical ingenuity of the Chinese state.

Its stock price is not a reflection of discounted cash flows; it is a geopolitical sentiment index. The price rises when China demonstrates technological defiance (like the Kirin chip) and falls when the U.S. tightens the screws. Traditional valuation is a fool’s errand.

The only way to value SMIC is as a call option on China’s technological sovereignty. The premium is high, the volatility is extreme, and the payoff is binary. The biggest risk is not a bad quarter; it is a geopolitical event that forces the U.S. to move from targeted restrictions to a full, crippling blockade. Conversely, the biggest catalyst would not be a new product, but a geopolitical détente that eases sanctions. Everything else is just noise.

Disclaimer:

The content does not constitute any kind of investment or financial advice. Kindly reach out to your advisor for any investment-related advice. Please refer to the tab “Legal | Disclaimer” to read the complete disclaimer.