The Coordination Economy: How Palantir Solved the Problem Everyone Else Ignored

In a world of fragmented systems, the most valuable software isn’t smarter—it’s the one that makes everything work together

TL;DR:

Palantir built an enterprise operating system, not an app — solving the fundamental coordination problem across fragmented systems with its Ontology, much like MS-DOS unified early PC hardware chaos.

The company’s “heavy” architecture was a misunderstood feature, not a bug — enabling real-time decision execution, not just analysis, by integrating deeply into an organization’s operational substrate.

In the AI era, Palantir’s infrastructure may be indispensable — providing the foundation that large language models can actually act on, positioning it as the coordination layer of the modern enterprise stack.

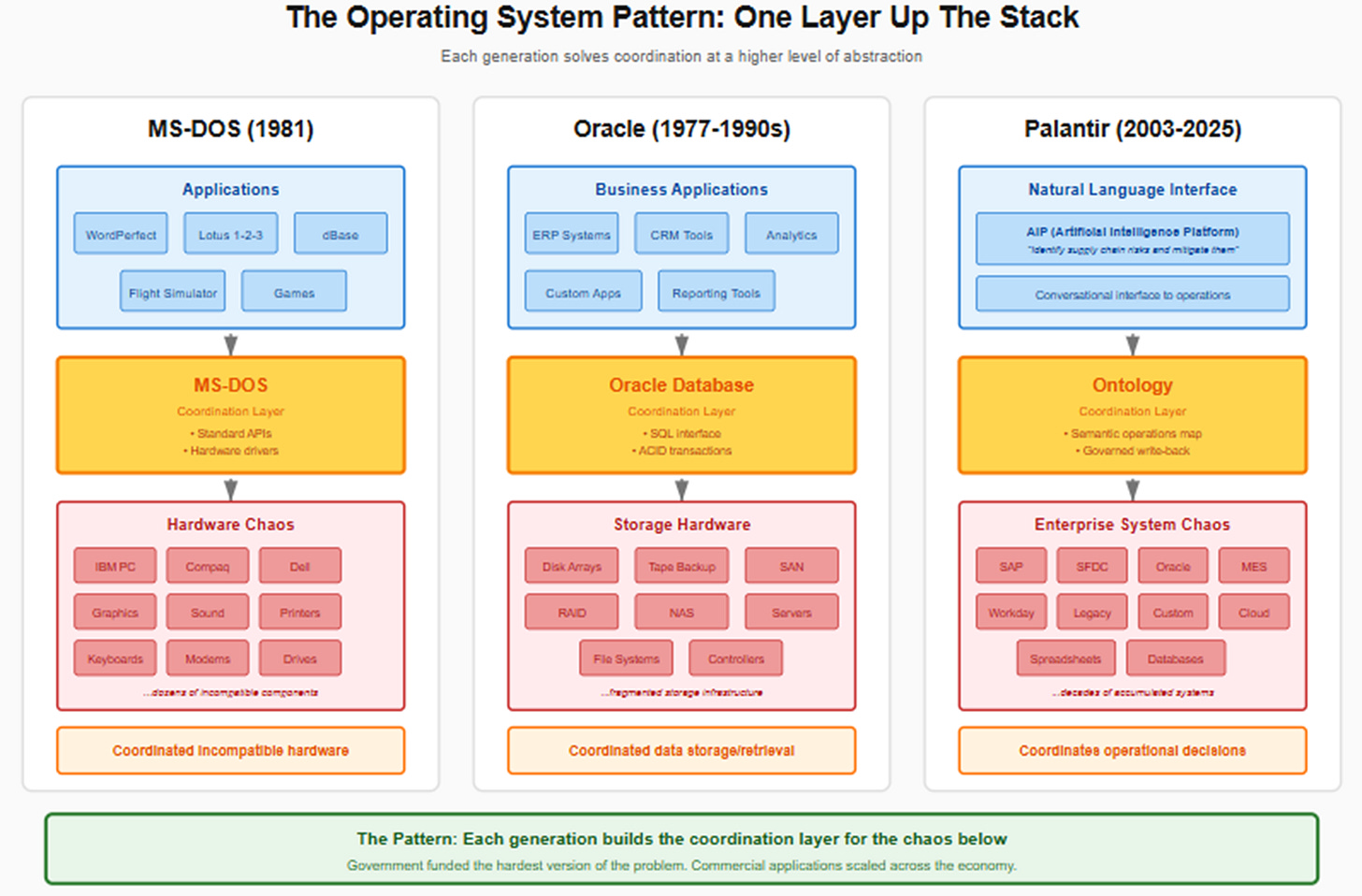

In August 1981, IBM released the Personal Computer. By early 1982, the market was flooded with “IBM-compatible” clones from Compaq, Columbia Data Products, Eagle Computer, and dozens of others. This created an immediate problem: the PC ecosystem became a chaotic bazaar of incompatible components. A printer from one manufacturer wouldn’t work with a graphics card from another. Software written for one hardware configuration would fail spectacularly on a different one, even if both machines claimed to be “IBM-compatible.” The promise of personal computing was being strangled by fragmentation.

The solution that emerged wasn’t elegant. MS-DOS, the operating system that Microsoft licensed to IBM and then sold to clone manufacturers, was primitive compared to Apple’s integrated system software and laughably crude next to the sophisticated Unix variants running on minicomputers. It had a command-line interface that required memorizing arcane commands. Its memory management was limited. Its multitasking was non-existent. By any technical measure, MS-DOS was inferior to alternatives.

But MS-DOS solved a problem that none of the technically superior alternatives addressed: it provided a standard set of rules—application programming interfaces, hardware drivers, and software conventions—that told disparate components how to work together. It gave software developers a predictable environment to build for. More importantly, it created a common language that organized chaos. The value wasn’t in any particular feature of MS-DOS itself. It was in the coordination it enabled across an otherwise incompatible ecosystem.

Forty years later, enterprises face a remarkably similar problem. And Palantir Technologies, a company that has confounded observers for two decades with its “heavy” approach to software, may have spent those years building the answer—an operating system for operational decision-making that looked wrong for the SaaS era but may be precisely right for the AI age. The world is only now becoming messy enough to understand what they built.

The Enterprise Bazaar

When Palantir was founded in 2003 to help intelligence agencies respond to the failures revealed by September 11th, the founders discovered something unexpected. The problem facing analysts wasn’t a lack of data or even a shortage of analytical tools. The problem was structural: critical data lived in dozens of incompatible systems—some dating back decades—with no common language between them. An intelligence analyst trying to connect terrorist financing patterns stored in one database with travel records in another system and communications intercepts in a third faced exactly the coordination problem that plagued the 1981 personal computer market.

This wasn’t unique to government. Walk into any large enterprise and you’ll find the same pattern: a digital bazaar accumulated over decades of technology decisions. There’s a 1990s-era SAP system handling finance, a Salesforce instance managing sales pipelines, proprietary manufacturing execution systems running factory floors, historians tracking equipment telemetry, and thousands upon thousands of Excel spreadsheets serving as the connective tissue between all of them. Each system speaks its own language. Each protects its data according to its own rules. And critically, each was designed to analyze and report on information, not to coordinate action across the enterprise.

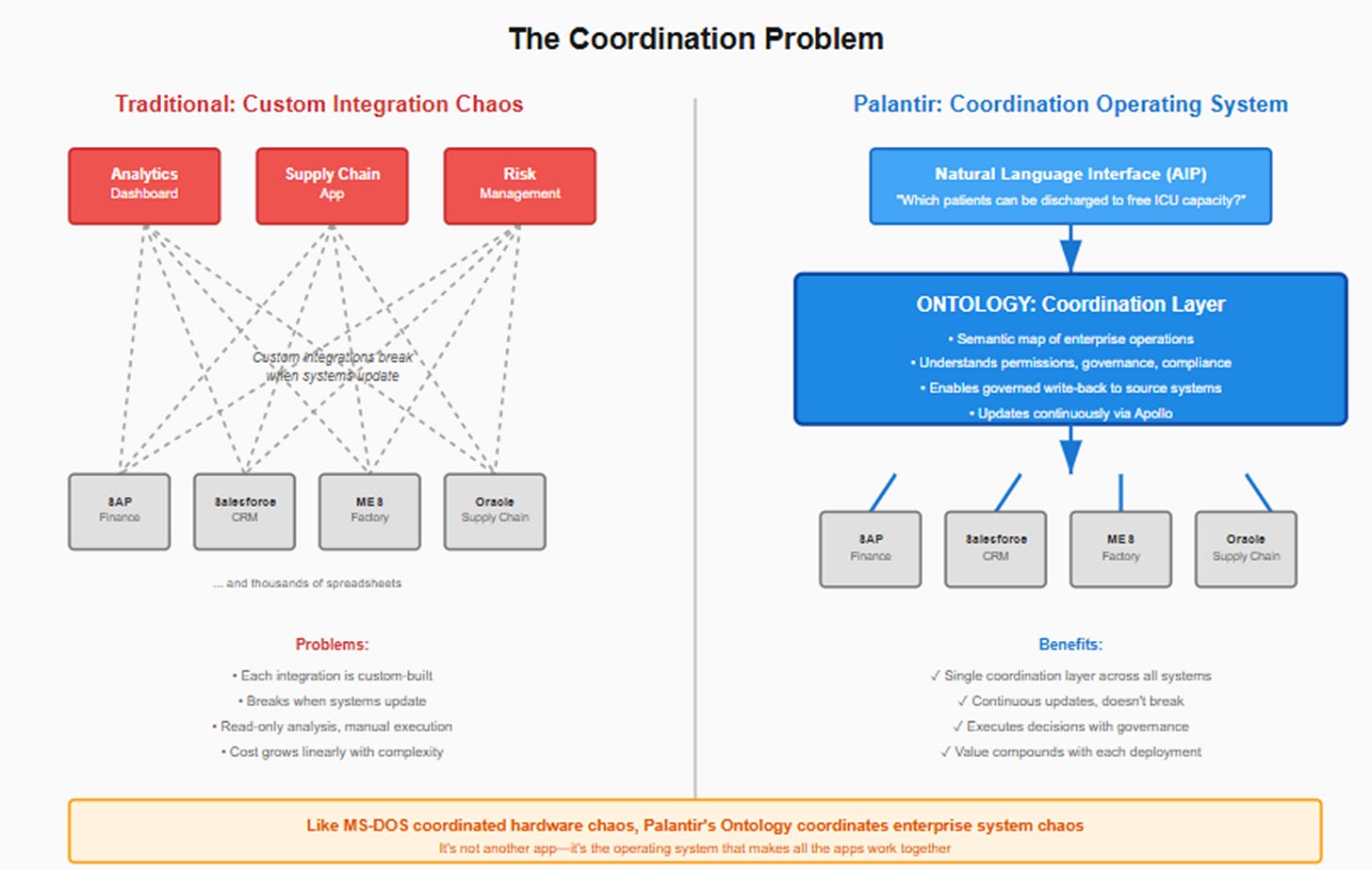

The conventional solution to this fragmentation is armies of systems integrators—consultancies that manually build bridges between systems for each new business initiative. This approach works after a fashion, but it scales poorly. Every integration is custom-built for a specific purpose. When underlying systems get updated or replaced, the bridges break and must be rebuilt. The cost and complexity of coordination grows linearly with the number of systems involved. Most problematically, the integrators build once and move on; there’s no mechanism to keep the coordination layer current as business needs evolve.

Palantir’s founding insight wasn’t that enterprises needed better applications to add to this bazaar. It was that they needed something that didn’t exist: a common abstraction layer underneath it all that could provide coordination the way MS-DOS provided coordination for incompatible PC components.

The Ontology as Translation Layer

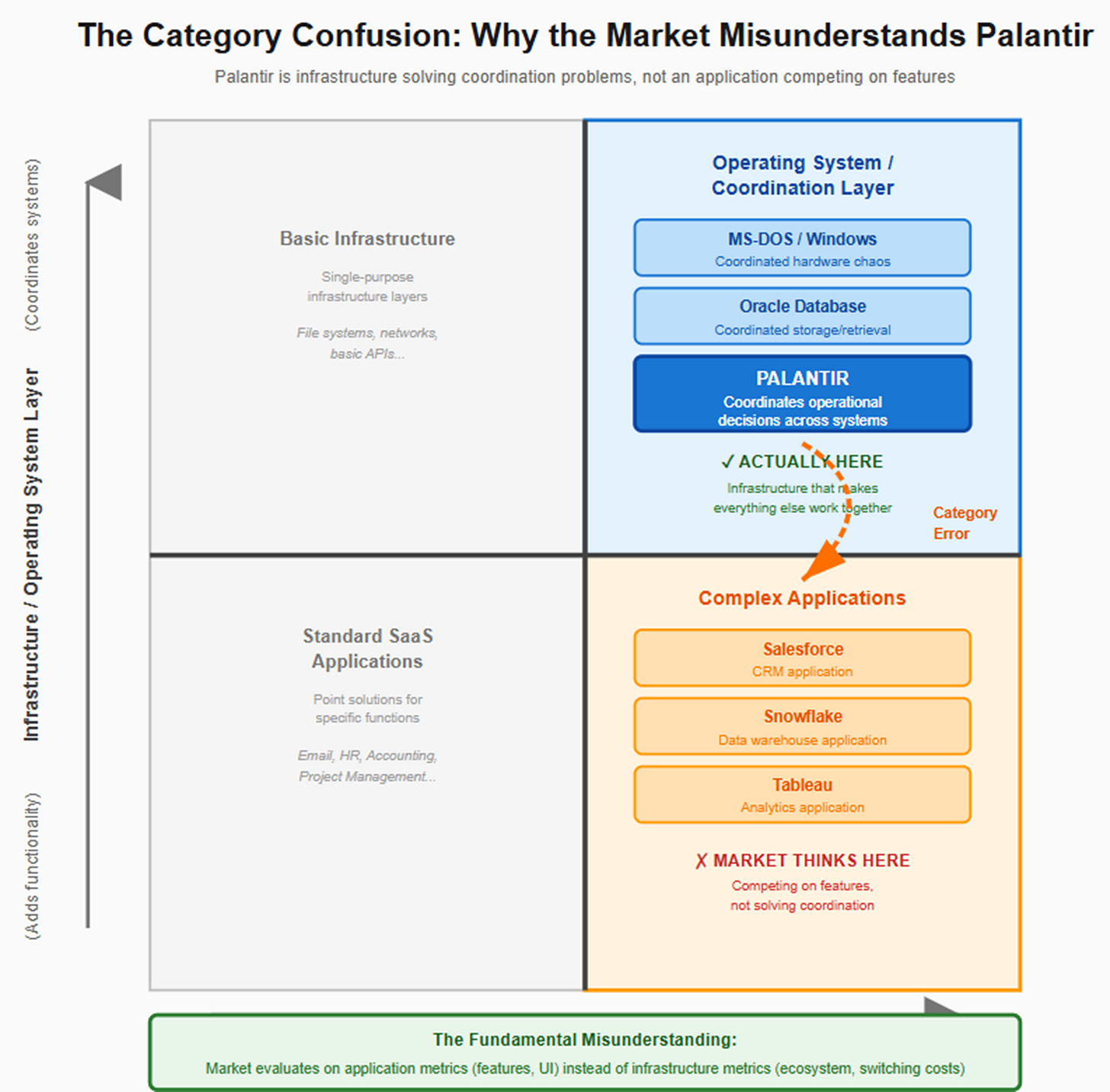

What Palantir built over its first decade was fundamentally different from what the market expected when it evaluated software companies. While competitors built better data warehouses for storing information or more sophisticated analytics tools for deriving insights—better stalls for the existing bazaar—Palantir built what amounts to an operating system for operational decision-making.

At the center of this system is what Palantir calls the Ontology. It’s not a database that stores copies of data, and it’s not a data lake that pools information from various sources. The Ontology is a semantic map of an enterprise’s operations. It understands what each system does, what the data in each system means, and critically, how different pieces relate to each other in the context of actual business operations. More importantly, the Ontology doesn’t just map data—it maps permissions, governance rules, and compliance requirements, so that when something needs to happen, when a decision needs to be made and executed, the system knows who can authorize what, where the permissions reside, and how to safely write changes back to source systems.

This last point is crucial and represents a fundamental architectural difference from traditional enterprise software. A data warehouse extracts information from operational systems to analyze it in a separate environment. The analysis might inform decisions, but executing those decisions requires going back to each individual system and making changes manually. Palantir’s architecture leaves data where it lives and creates a logical coordination layer on top of it. When a supply chain manager needs to adjust production schedules in response to a disruption, the Ontology translates that intent into the specific transactions required across ERP systems, manufacturing execution systems, and logistics systems—maintaining complete audit trails and respecting granular access controls the entire way through.

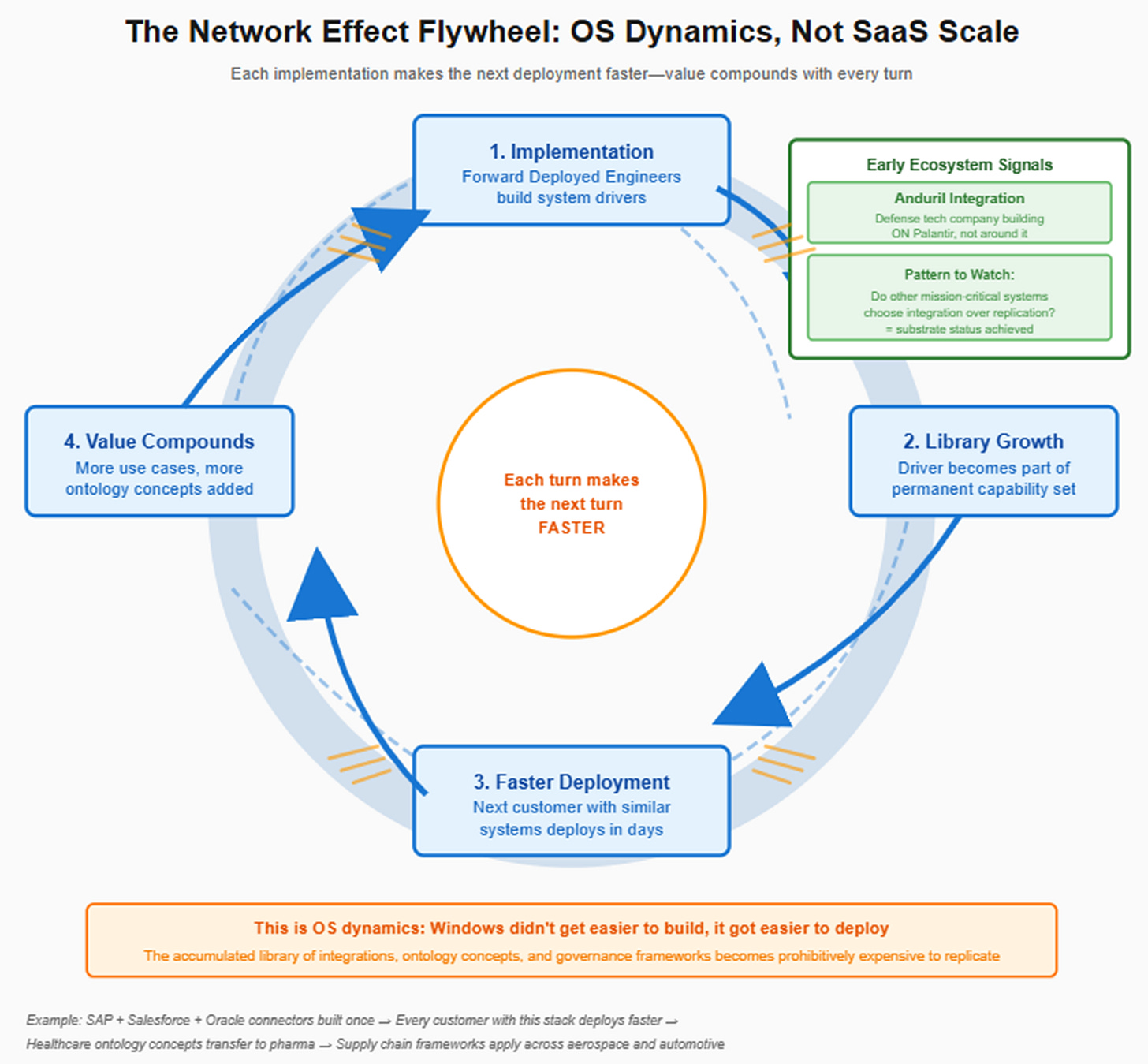

The reason Palantir looked “heavy” and services-intensive for so long is that building this coordination layer required solving each enterprise’s unique chaos individually. The company’s Forward Deployed Engineers—frequently cited by critics as evidence that Palantir was really a consulting business disguised as software—were doing something fundamentally different from traditional systems integration. They were installing the operating system. They were mapping the initial territory, understanding how each enterprise’s bazaar was actually organized, and building the “drivers” that would allow Palantir’s coordination layer to work in that specific environment.

But once installed, the operating system doesn’t need to be rebuilt every time business requirements change. It updates continuously via Apollo, Palantir’s deployment infrastructure that can push changes to cloud instances, on-premise installations, and even air-gapped classified networks. This is the software equivalent of Windows Update, not a recurring consulting engagement. The initial work is intensive, but it compounds: each installation makes the next one faster because Palantir’s library of system integrations and business logic modules grows with every deployment.

The GUI Moment

In January 1984, Apple released the Macintosh with a graphical user interface. The underlying computing architecture wasn’t dramatically more powerful than command-line systems available at the time. But the GUI made that power accessible to people who would never learn to navigate a command line. You didn’t need to memorize syntax or understand file system hierarchies. You could simply point at what you wanted and click. The abstraction layer of the operating system—coordinating between hardware and software—now had an intuitive interface layer on top that made the system’s capabilities available to non-technical users.

In April 2023, Palantir released AIP, the Artificial Intelligence Platform. The timing was deliberate. Large language models had just demonstrated they could serve as a natural language interface to complex software systems. But most companies attempting to deploy these models were discovering exactly the problem Palantir had encountered twenty years earlier: the LLM was powerful, but there was no coherent substrate for it to act upon. Asking ChatGPT to “identify the biggest supply chain risk and mitigate it” fails not because the model lacks intelligence, but because it can’t access your fragmented data, doesn’t understand your specific business context, has no awareness of your compliance requirements, and has no ability to safely execute changes across your operational systems.

AIP works because it sits on top of the Ontology. When a user asks a question or issues a command in natural language, AIP translates it into a series of actions that the Ontology can coordinate across the enterprise. The large language model provides the interface layer—the conversational GUI for enterprise operations. The Ontology provides the substrate—the coordination layer that knows how to actually execute decisions across fragmented systems. The result is that for the first time, decision-makers can interact with their entire operation through conversation rather than navigating through dozens of separate applications.

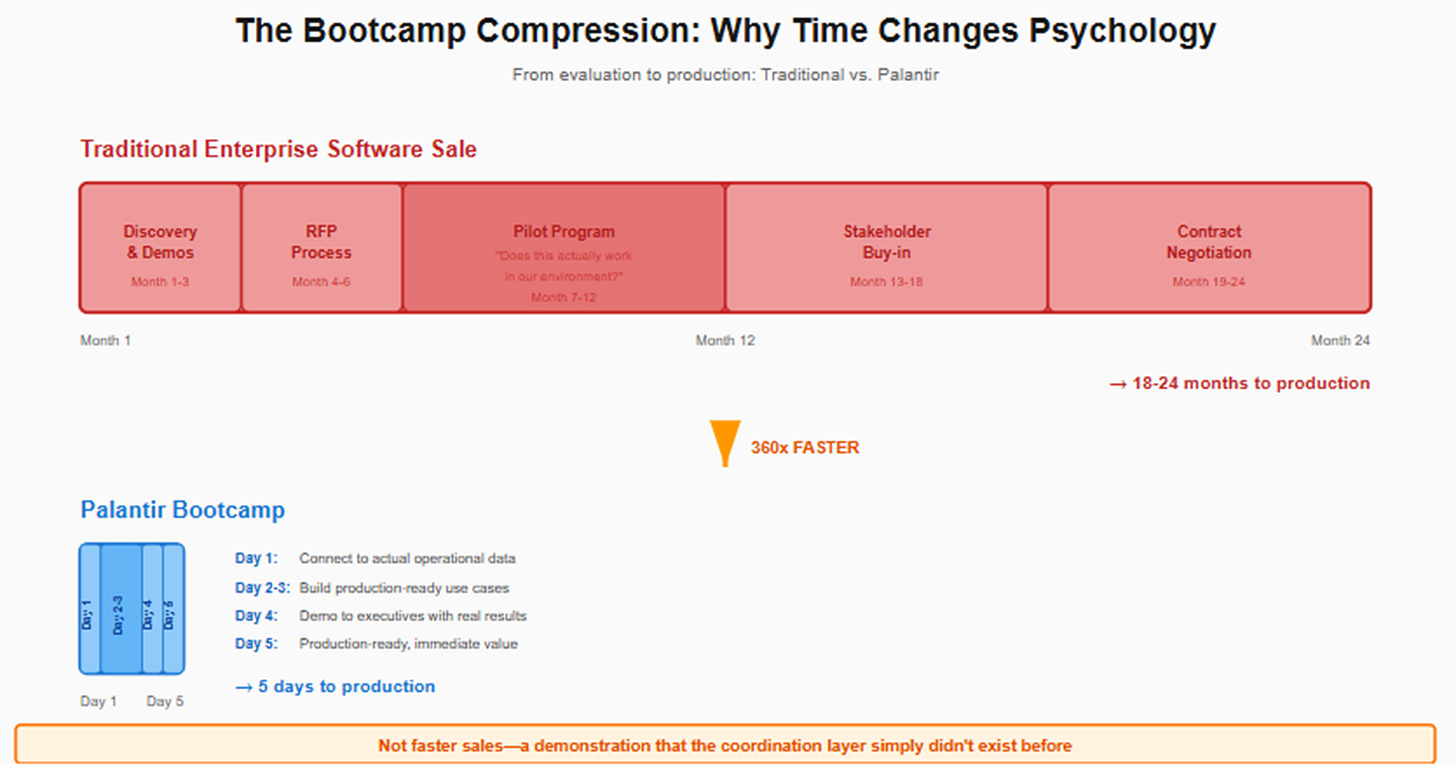

This is where Palantir’s “bootcamp” go-to-market approach becomes strategically significant. In a traditional enterprise software sale, the vendor demonstrates the product in a controlled environment, the customer runs an extended pilot program to verify it works in their context, and slowly, over many months, confidence builds toward a purchase decision. Palantir inverted this process. In a bootcamp, they bring AIP directly to the customer’s actual operational data and in five days build production-ready use cases that demonstrate value immediately and viscerally.

Consider a hospital system struggling with patient flow and bed allocation. In a bootcamp, Palantir’s team connects AIP to the hospital’s electronic health records, scheduling systems, and capacity management tools. By day three, administrators are using natural language to ask questions like “which patients can be safely discharged today to free up ICU capacity” and receiving answers that account for medical necessity, insurance authorization status, and post-discharge care availability. By day five, the system isn’t just answering questions—it’s proposing specific bed allocations, simulating the operational impact, and upon approval, executing the necessary updates across multiple systems while maintaining complete audit trails for regulatory compliance.

This isn’t just faster sales. It’s a demonstration of a category difference. The customer isn’t evaluating whether Palantir’s features compare favorably to a competitor’s feature set. They’re experiencing what it means to have a coordination layer—an operating system—that simply didn’t exist before. It’s the equivalent of putting a Macintosh in front of someone who had only ever used a command line. The visceral understanding of what becomes possible changes the adoption calculus entirely.

What the Market Misunderstands

Wall Street currently values Palantir as a high-growth software application company successfully riding the generative AI wave. This framing leads to several fundamental misunderstandings about what the company has built and where its defensibility comes from.

The first misunderstanding concerns the nature of Palantir’s competitive moat. Analysts and investors often focus on whether Palantir’s artificial intelligence models are superior to those of competitors. But this misses the point entirely. Palantir doesn’t compete on model quality—they actively use large language models from OpenAI, Anthropic, and other providers. The moat isn’t the model. The moat is the twenty years of accumulated work mapping enterprise chaos into coherent ontologies. It’s the institutional knowledge of how to safely coordinate action across thousands of different system configurations, data formats, and governance frameworks. This is architectural knowledge that compounds with each deployment and cannot be quickly replicated, much like the driver libraries and hardware compatibility layers that made Windows valuable weren’t about Microsoft having superior code, but about having solved the coordination problem comprehensively.

The second misunderstanding is the persistent critique that Palantir is really just “consulting with a software wrapper.” This view confuses the initial deployment phase with the ongoing business model. Yes, the initial implementation is intensive—installing an operating system always is, whether it’s configuring Windows for an enterprise deployment or mapping Palantir’s Ontology to a specific organization’s operational reality. But once installed, the customer has a continuously updating coordination layer that works across their entire enterprise. The unit economics prove the point: Palantir operates at 82% gross margins and has expanded operating margins from 22% in 2022 to 46% currently. These are software economics, not consulting economics. The Forward Deployed Engineers aren’t staff augmentation; they’re specialized field engineers who install and configure a complex system, then hand it over to run autonomously.

The third misunderstanding concerns the threat from hyperscale cloud providers. The common bear case argues that Amazon Web Services, Microsoft Azure, or Google Cloud Platform will simply build similar capabilities and bundle them with cloud infrastructure, leveraging their massive scale and existing customer relationships to capture the market. But this analysis conflates different layers of the stack. Hyperscalers provide the compute and storage layer—they’re the hardware infrastructure of the cloud era. Palantir provides the coordination layer that works across any infrastructure, including competitors’ clouds and even on-premise systems that will never move to the public cloud.

More telling is how companies building mission-critical systems choose to integrate with Palantir rather than replicate its functionality. Anduril, the defense technology company building autonomous drones and sensor networks, could theoretically build its own command and control coordination system. Instead, they treat Palantir as infrastructure—the layer that coordinates their systems with everything else in a military operation. This is the behavior you see when something transitions from vendor to substrate, from application to operating system.

The fourth and perhaps most consequential misunderstanding concerns the total addressable market. Because Palantir originated in defense and intelligence work, analysts often categorize it as a government contractor with inherently limited commercial applicability. This is a category error with clear historical precedent.

In 1977, Larry Ellison won a contract with the Central Intelligence Agency to build a relational database for a classified project codenamed “Oracle.” For the company’s early years, it was perceived as a government contractor doing specialized work for intelligence agencies with unique requirements. But Ellison understood something the market didn’t immediately recognize: the CIA’s database problem—reliably storing, retrieving, and managing structured data—wasn’t actually unique to intelligence work. It was universal. Every enterprise needed the same capabilities. The CIA simply had the hardest version of the problem and the budget to solve it properly, which meant the technology developed for intelligence work was more than adequate for commercial applications.

By the 1990s, Oracle Database was the enterprise standard, running everything from retail point-of-sale systems to financial services trading platforms to manufacturing resource planning. The government origin hadn’t limited the total addressable market—it had validated the technology under the most demanding conditions imaginable and funded the development of capabilities that then scaled across the entire economy.

Palantir is following precisely the same trajectory, one layer up the technology stack. Oracle solved the problem of data storage and retrieval. Palantir is solving the problem of coordination and decision-making across fragmented operational systems. And this coordination problem is equally universal. Airbus uses Palantir to coordinate manufacturing operations across global supply chains and assembly facilities. Morgan Stanley uses it to coordinate trading operations and risk management across dozens of legacy systems. Merck uses it for drug development timelines and pharmaceutical supply chain coordination. United Healthcare uses it to coordinate claims processing and care management across a sprawling healthcare delivery network.

These aren’t “defense-adjacent” use cases that happen to work for Palantir because of some tangential similarity to military operations. They’re the core operational challenges of running complex organizations—the same coordination problems that intelligence agencies faced in connecting disparate data sources and executing time-sensitive operations, just manifesting in commercial contexts. The government origin wasn’t a constraint on the addressable market. It was proof that the solution works when failure carries catastrophic consequences.

The Network Effect of Coordination

Operating systems exhibit a specific and powerful type of network effect. Each application built for Windows made Windows more valuable to end users, which increased the installed base, which attracted more developers to build for the platform, which led to more applications. The system was self-reinforcing, and once established, it became effectively unassailable.

Palantir is reaching the early stages of this dynamic. Each implementation requires mapping that specific enterprise’s operational systems—building the “drivers” that allow Palantir’s coordination layer to interface with those particular technologies. But those drivers don’t disappear after one deployment; they become part of Palantir’s permanent library of capabilities. The next company using SAP for finance, Salesforce for sales, and Oracle for supply chain management can deploy faster because the fundamental connectors already exist in Palantir’s system. The Ontology concepts developed for supply chain coordination in automotive manufacturing transfer directly to aerospace or industrial equipment. The governance frameworks built for handling classified intelligence data map naturally to healthcare organizations managing patient information under HIPAA regulations.

This is compounding in the classical sense: the value of the accumulated library grows non-linearly as each new deployment both benefits from and contributes to the collective body of integration knowledge. And as this library becomes more comprehensive, the cost and time required to achieve the same level of integration capability through custom development becomes increasingly prohibitive for any potential competitor.

More importantly, there are early signals that other companies building mission-critical operational systems are choosing to build on top of Palantir’s coordination layer rather than attempting to build around it or replicate it. The Anduril integration is the clearest proof of concept to date. Anduril’s autonomous systems—drones, towers, submarines—represent cutting-edge defense technology. They could justify building proprietary coordination and command systems. Instead, they’ve integrated with Palantir as the substrate that connects their capabilities with broader military operations.

If this pattern continues—if more companies in defense technology, healthcare technology, financial services infrastructure, or industrial automation choose integration with Palantir over replication of its functionality—it would signal that Palantir is making the transition from being a vendor that customers buy from to being a substrate that others build upon. That’s the defining characteristic of an operating system achieving market position.

The Valuation Reality

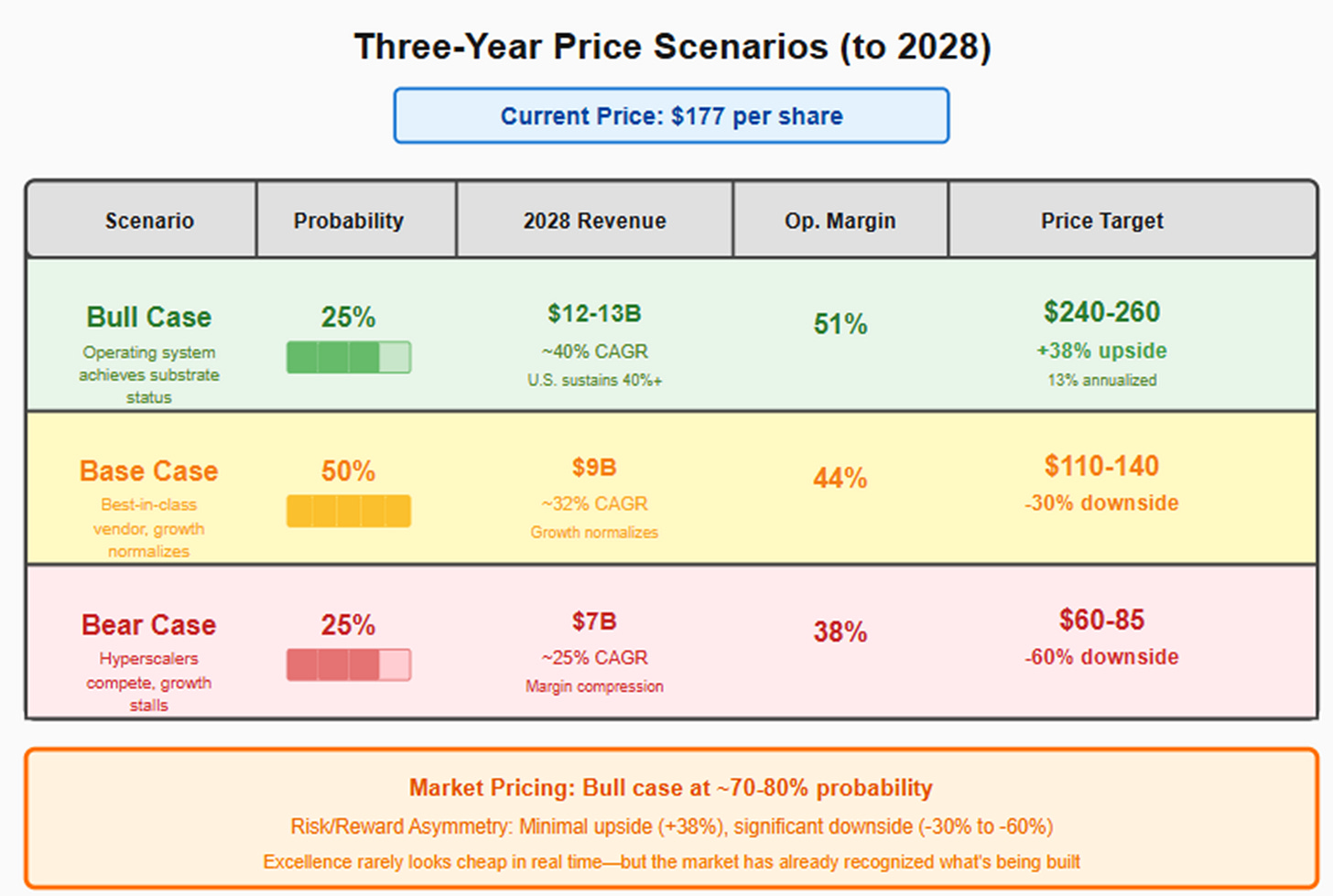

At the current price of approximately $177 per share and a market capitalization exceeding $400 billion, Palantir trades at roughly 157 times projected earnings for 2026. This valuation necessarily embeds specific assumptions about what the company will become over the next several years.

If Palantir executes on the most optimistic version of its strategy—sustaining U.S. commercial growth rates above 40%, expanding operating margins toward 50%, and successfully replicating the bootcamp model internationally—revenue could reach $12 billion to $13 billion by 2028 with operating margins around 51%. If the market continues to value the company at a 40x earnings multiple, consistent with businesses that achieve true infrastructure status, that trajectory implies a stock price in the range of $240 to $260. This is the bull case: Palantir becomes the standard coordination layer for enterprise operations, network effects strengthen with scale, and ecosystem development validates the operating system thesis. Looking at current valuation, the market appears to be pricing this outcome at roughly 70 to 80 percent probability.

A more measured assessment would suggest a base case where growth normalizes to the low-to-mid 30 percent range as the initial wave of early adopters is penetrated and expansion becomes more dependent on broader market education. In this scenario, Europe remains challenged with growth in the high single digits, and operating margins plateau around 44% as continued scaling requires ongoing investment in Forward Deployed Engineering capacity to handle implementation demands. This path leads to approximately $9 billion in revenue by 2028. At an earnings multiple of 30x—appropriate for a high-quality but maturing growth business—the mathematics suggest a stock price of $110 to $140 per share. This outcome reflects Palantir succeeding as a best-in-class vendor to complex enterprises with sophisticated operational challenges, but not achieving the substrate status that would justify infrastructure-level valuation multiples.

The bear case activates if hyperscale cloud providers successfully build competing coordination capabilities that achieve meaningful customer traction, if Palantir’s customer base fails to diversify and concentration risk increases rather than decreases, or if the bootcamp model proves unable to scale internationally due to cultural or regulatory barriers. Under these conditions, revenue growth of approximately 25% would lead to $7 billion in 2028, operating margins would compress toward 38% due to pricing pressure and the need for higher sales and implementation costs, and the market would likely value the business at 22x earnings. This scenario implies a stock price of $60 to $85 per share and would represent Palantir as a large but ultimately bounded software company serving a specific niche of highly complex operational environments.

The distribution of these outcomes matters more than any individual scenario. At $177 per share, even the bull case offers only modest upside over a three-year period—approximately 45%, or a 13% annualized return. The base case implies meaningful downside of 30 to 40 percent. The bear case suggests severe downside of 50 to 65 percent. This is the profile of a security where the market has already priced in an optimistic scenario as the baseline expectation.

For investors, the salient question isn’t whether Palantir is a good business—the operational metrics clearly demonstrate that it is. The question is whether at current valuation the market has already recognized what Palantir is in the process of becoming, or whether meaningful mispricing remains. The answer will reveal itself through observable indicators over the next 24 months.

What to Watch

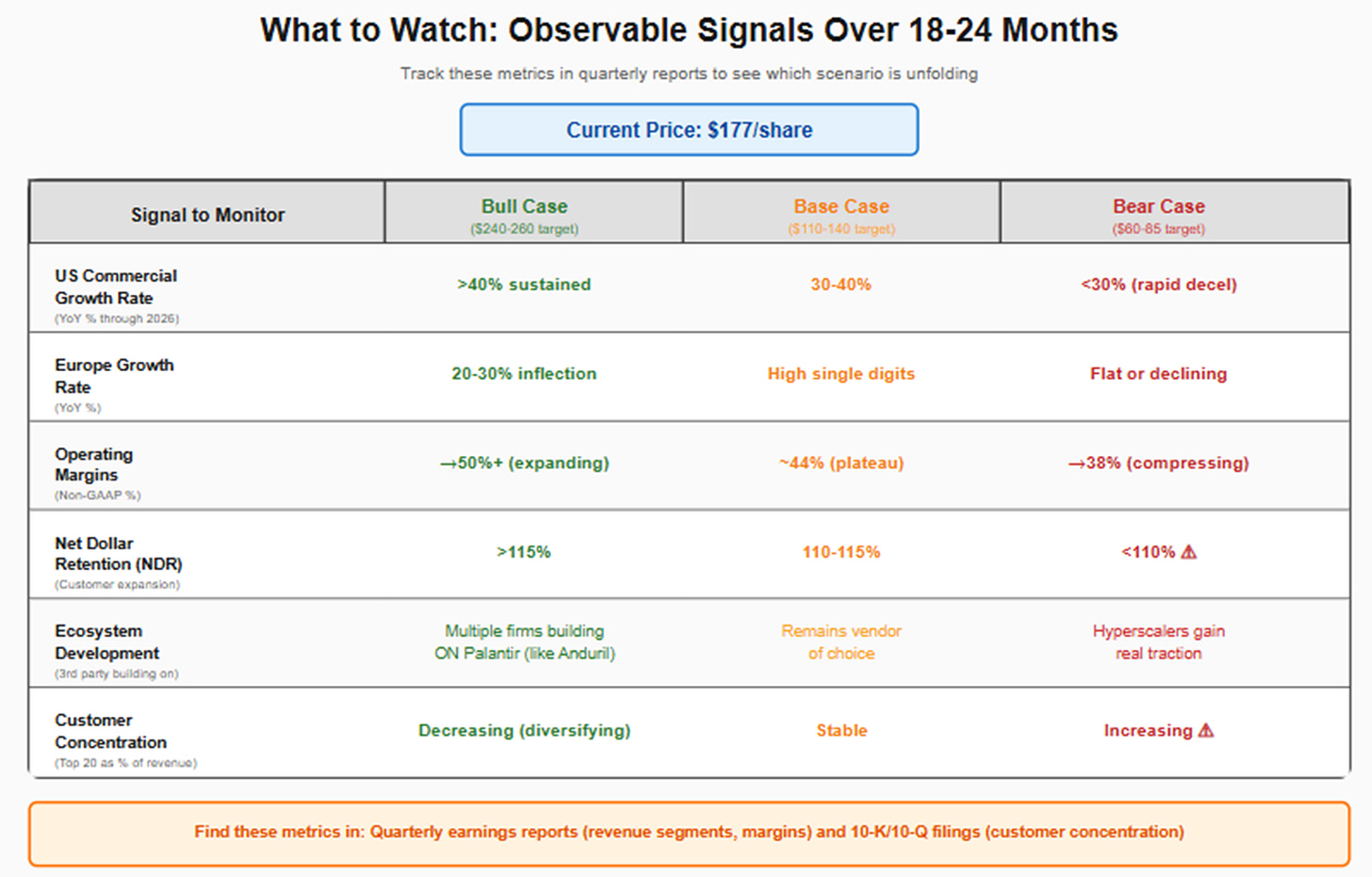

Several specific signals over the next two to three years will reveal which of these scenarios is unfolding in practice.

On the adoption curve, the bull case requires U.S. commercial revenue growth to sustain levels above 40% through 2026. The recent year-over-year growth rate of 93% cannot and will not continue indefinitely—it’s mathematically impossible to sustain triple-digit growth off a base approaching $1 billion in quarterly revenue. But if growth remains elevated in the 40% to 50% range even as the base scales, it signals that the addressable market is substantially larger and the adoption curve substantially earlier-stage than skeptics currently believe. More important than the absolute growth rate is the composition: watch whether expansion is driven primarily by net new customer additions or by deepening penetration and expansion within the existing base. Operating systems win initially by achieving broad installation across an ecosystem. They create lasting value by becoming progressively more valuable to those who have adopted them.

The international question demands resolution within the next 18 to 24 months. Europe has been growing at low single-digit rates while the U.S. business surges, and this divergence creates two competing interpretations. Bulls argue it reflects strategic prioritization—Palantir is rationally focusing resources on the market with the fastest procurement cycles and the greatest cultural willingness to adopt new operational paradigms. Bears argue it’s evidence that the model doesn’t travel, that something specific about U.S. enterprises or U.S. government procurement makes Palantir work domestically but limits applicability abroad. If Europe and Asia-Pacific inflect to 20% to 30% growth rates, it would validate the thesis that the operational coordination problem is truly horizontal and that the apparent U.S. concentration reflects prioritization rather than limitation. If these markets remain stagnant or even deteriorate, it would suggest the addressable market is bounded in ways that fundamentally limit the bull case.

Operating margin trajectory will reveal whether the business model exhibits the leverage characteristics of an operating system or the linear cost structure of a services business. The company has expanded operating margins from 22% in 2022 to 46% currently, demonstrating substantial operating leverage to date. If margins compress as Palantir hires additional Forward Deployed Engineers and expands implementation capacity to meet demand, it would indicate the business isn’t as capital-light as current margins suggest. If margins hold steady or continue expanding toward 50%, it validates that the intensive work of initial implementation is increasingly front-loaded and that the software coordination layer scales with minimal incremental cost once deployed.

The ecosystem question may ultimately be the most important signal of all. Anduril’s decision to integrate with Palantir’s coordination layer rather than building proprietary command and control infrastructure is a single data point. If that pattern replicates—if other companies building mission-critical systems in defense technology, healthcare delivery, financial services, or industrial operations choose to build on Palantir rather than around it—it would confirm that Palantir is transitioning from vendor to substrate, from application provider to infrastructure layer. If instead each customer relationship remains vertically integrated, with Palantir serving as a vendor of choice rather than a shared foundation, it suggests the company will achieve success as a large software business but not the compounding network effects that characterize true operating systems.

Conversely, the bear case would activate if revenue growth decelerates rapidly to 25% or below in the absence of obvious macroeconomic headwinds, if a hyperscale cloud provider launches a credible competing coordination capability that demonstrates real customer traction rather than vaporware demonstrations, if customer concentration increases rather than diversifies despite the expanding customer base, or if management commentary shifts from “demand is overwhelming our capacity” to “competitive intensity is increasing.” Net Revenue Retention falling below 110% would be particularly concerning—it would indicate that customers aren’t finding additional use cases and expanding their deployments after the initial implementation, which would contradict the thesis that Palantir becomes more valuable over time within an organization.

The Coordination Economy

In 1985, critics of MS-DOS were technically correct in virtually every particular criticism they leveled. It was clunky in operation, severely limited in capability, and objectively inferior to alternative operating systems like Apple’s Macintosh System Software or the various Unix implementations running on more powerful hardware. What these critics fundamentally misunderstood was that DOS wasn’t competing on technical sophistication. It was solving a coordination problem that none of the technically superior alternatives addressed: making thousands of incompatible hardware components and software applications work together as a coherent system. The value wasn’t in any particular feature or capability that DOS itself provided. The value was in organizing an otherwise chaotic and incompatible ecosystem into something predictable and usable.

By the late 1980s, Microsoft’s position had become effectively unassailable, not because the technology underlying DOS and Windows was irreplicable—several companies built operating systems with superior technical characteristics—but because the coordination problem had been solved and the world had standardized around Microsoft’s solution. The switching costs weren’t primarily technical. They were the accumulated investments in applications, drivers, workflows, and institutional knowledge that had been built on the assumption that DOS was the substrate.

Palantir may be approaching a similar inflection point today. For twenty years, the company has looked wrong to outside observers—too heavy, too expensive, too complex, too focused on problems that seemed specific to a narrow set of government and industrial use cases. It looked wrong precisely because it was building for a coordination problem that the broader market hadn’t yet recognized it needed to solve. While the software industry celebrated lightweight, self-service, API-driven architectures that let customers assemble their own solutions, Palantir built something that looked like the opposite: an opinionated, tightly-integrated operating system for operational decision-making.

The question facing investors today isn’t whether the technology works. The bootcamps prove it works, and customer expansion rates confirm that organizations find it valuable enough to deploy it across progressively more of their operations. The question is whether we’re witnessing the same dynamic that played out with MS-DOS: an initially clunky, expensive solution to a coordination problem becoming indispensable as the world comes to understand that it needs coordination more than it needs another optimized individual component.

If Palantir is indeed building an operating system for enterprise operations, then the critics who attack its complexity and its departure from modern software orthodoxy have fundamentally missed the point. Operating systems are supposed to handle complexity so that everything built on top of them doesn’t have to. The heaviness isn’t a design flaw or a relic of outdated thinking. In a world where every enterprise is a fragmented bazaar of incompatible systems accumulated over decades, the heaviness is the solution.

The misfit may have been fitting the problem all along. The world is only now becoming sufficiently complex, sufficiently AI-dependent, and sufficiently operationally sophisticated to notice what twenty years of building in apparent obscurity has created. Whether that realization comes early enough to justify current valuations is a different question entirely—one that will be answered not by the quality of what Palantir has built, but by the price paid to own a piece of it. Excellence, after all, rarely looks cheap in real time. It’s only in retrospect, once the coordination problem is solved and the world has moved on, that we recognize what was being built while everyone else was looking the other way.

Disclaimer:

The content does not constitute any kind of investment or financial advice. Kindly reach out to your advisor for any investment-related advice. Please refer to the tab “Legal | Disclaimer” to read the complete disclaimer.