The Front Door Moved: How AI Agents Are Rewriting Software's Moats

From SAP’s standardization of business processes to today’s agent-mediated workflows, the battle for software’s defensibility is shifting from features to control over the access layer.

The front door to software has moved — AI agents now mediate how users access applications, shifting power away from many Systems of Engagement toward Systems of Record and AI-native insurgents.

Defensibility is being rewritten — survival hinges on agent-native architectures, proprietary data moats, integration control, and new distribution models optimized for agent ecosystems.

Markets are repricing ruthlessly — software vendors must prove “agent-era viability” across execution, business model, and distribution, or risk being treated as obsolete before the disruption fully plays out.

The Great Standardization

In 1992, most Fortune 500 companies ran their core business operations on custom-built software systems. Each company employed armies of internal developers and consultants to build and maintain financial systems, inventory management, and HR platforms that were, functionally speaking, nearly identical across industries. Every enterprise was, in effect, a software company, dedicating enormous resources to reinventing the same operational processes that their competitors had already built.

Then came SAP with a radical proposition: what if the core business processes that every company thought made them unique could be standardized into packaged software? Not just the code, but the entire framework of how businesses should operate—from procurement to accounting to human resources.

The resistance was fierce and predictable. IT departments pushed back violently. "Our business is unique," they argued. "These packaged systems will never handle our complexity. Our procurement process has seventeen approval stages because of our industry's specific requirements." The consultants agreed, naturally—custom implementations meant higher fees and longer engagements.

Yet by 2002, SAP had captured massive portions of the Fortune 500, not by being more customizable than the custom solutions, but by being more standardized. Companies discovered that their "unique" processes were, in fact, quite common. More importantly, they learned that standardization itself had value beyond the software—it enabled best practices, simplified training, and created efficiencies that custom solutions could never match.

The lesson was profound: when a technology shift occurs, value doesn't always flow to the most flexible or feature-rich solution. Sometimes it flows to the solution that successfully standardizes and controls the underlying process layer, creating switching costs and network effects that transcend the technology itself.

Today, we're witnessing a similar standardization, but this time the process being standardized isn't business operations—it's how users access software itself.

The Front Door Moved

For the past fifteen years, users accessed software through a relatively straightforward process: they opened applications directly, clicked search results, or navigated through bookmarks and shortcuts. The relationship was fundamentally direct—user to software vendor. If you needed to design an interface, you opened Figma. If you needed to track a project, you opened Asana. The software companies competed for your attention and built their businesses on direct relationships with users.

This created what we might call the "application bazaar"—a decentralized marketplace where value flowed to the vendors with the best products or the most effective distribution (usually meaning the highest Google search rankings). It was a vibrant, competitive landscape where thousands of specialized software companies could thrive by solving specific problems better than anyone else.

But something fundamental has changed. Today, an increasing number of users don't open Figma to design or Asana to manage projects. Instead, they state their intent to an AI agent: "Create a user interface mockup for a mobile banking app" or "Show me the status of the Q4 product launch and draft an update for the leadership team."

The agent—whether it's embedded in their operating system, browser, or productivity suite—intercepts this intent and decides which underlying applications to invoke. The user's primary relationship is no longer with Figma or Asana; it's with the agent. The front door to software has moved.

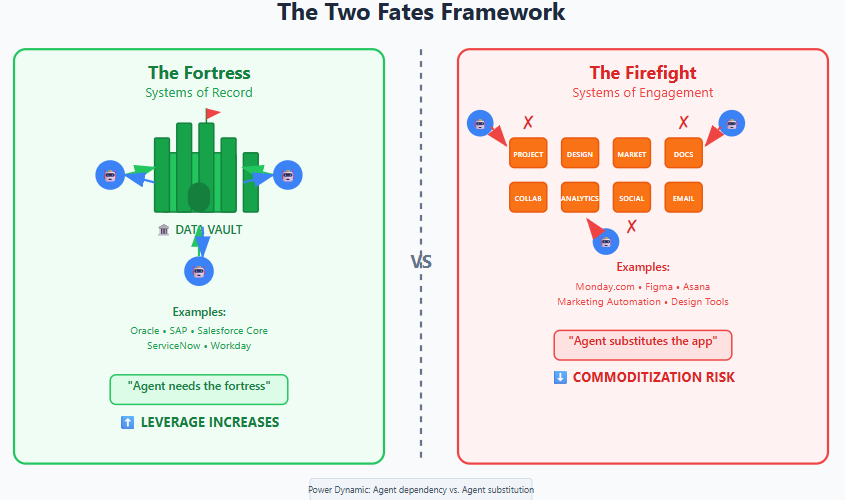

This shift is creating two very different fates for software companies, and understanding which fate awaits which type of software explains the current "SaaSmageddon" we're witnessing in public markets.

Fortress and Firefight: The Two Theaters of Software

Not all software is created equal when it comes to AI disruption. The market's current "guilty until proven innocent" approach to software valuation fails to distinguish between two fundamentally different categories of enterprise software, each with distinct economic characteristics and defensive capabilities.

The Fortress: Systems of Record

The first category consists of what we might call Systems of Record—the mission-critical backbone systems that store authoritative business data and enforce core processes. These include ERP systems, core CRM platforms, IT service management tools, and financial systems. Think Oracle, SAP, Salesforce's core platform, and ServiceNow.

These systems share several critical characteristics:

They contain the canonical version of business-critical data

They enforce compliance, audit trails, and business rules

They integrate deeply with dozens or hundreds of other systems

Replacement requires organization-wide change management

Failure can halt business operations or create regulatory violations

For these systems, the relationship with AI agents is fundamentally different. Agents don't replace these systems; they integrate with them. An agent that promises to "show me Q4 revenue by product line" must ultimately query Salesforce or SAP to get authoritative data. An agent that "creates a new customer record" must write to the system of record to ensure data integrity and trigger downstream processes.

This creates a power dynamic that favors the fortress: the agent needs the system of record more than the system of record needs any particular agent. This gives Systems of Record significant leverage in determining integration terms and the ability to build their own agents with privileged access to their data vaults.

The Firefight: Systems of Engagement

The second category consists of Systems of Engagement—the tools users interact with to create, collaborate, analyze, and manage work. This includes project management tools, design software, marketing automation platforms, analytics dashboards, and most productivity applications. Think Monday.com, Figma, various marketing tools, and specialized workflow applications.

These systems typically have:

Lower switching costs

Less integration complexity

Fewer compliance requirements

More focus on user experience than data authority

Business models built on direct user relationships

For Systems of Engagement, the AI agent relationship is far more threatening. When a user asks an agent to "create a project timeline with key milestones," the agent might generate this directly rather than opening a project management tool. When they request "a social media campaign for our product launch," the agent might create the entire campaign without touching a marketing automation platform.

The user's direct relationship with these tools—the foundation of their business models—is being intermediated by the agent.

Killing the DIY Myth

Before diving deeper into how AI agents are reshaping software, it's crucial to dispel a persistent myth that's creating unnecessary panic: the idea that AI will enable every company to build their own software, making all vendors obsolete.

As one astute observer noted, "I think the risk that companies build their own systems of record—ERP, ITSM, CRM etc—is incredibly low. Companies are not stupid. They have no competence here, the stakes are massively high, and regardless of how easy it is, they would still have to maintain and optimize it, which is, ultimately, a distraction from their actual business."

This insight reveals a fundamental misunderstanding in the "everyone becomes a developer" narrative. Yes, AI makes writing code easier. But writing code was never the primary barrier to enterprise software adoption. The real barriers are:

Data modeling and business logic: Understanding how complex business processes should be structured and enforced

Integration complexity: Connecting to dozens of existing systems without breaking anything

Compliance and audit requirements: Meeting regulatory standards and maintaining proper controls

Change management: Training organizations and managing transitions

Ongoing maintenance: Security updates, performance optimization, and feature evolution

Companies pay software vendors not because they can't figure out how to build software, but because they want to offload the risk and complexity of owning mission-critical systems. Just as the cloud made infrastructure "easier" to manage but companies still pay AWS rather than running their own data centers, AI making coding easier doesn't eliminate the fundamental value proposition of enterprise software vendors.

The DIY threat is real only at the edges—for highly technical companies with unique requirements or for simple, non-critical applications. For the vast majority of enterprise software, the question isn't whether companies can build their own; it's whether existing vendors can adapt to a world where agents mediate user relationships.

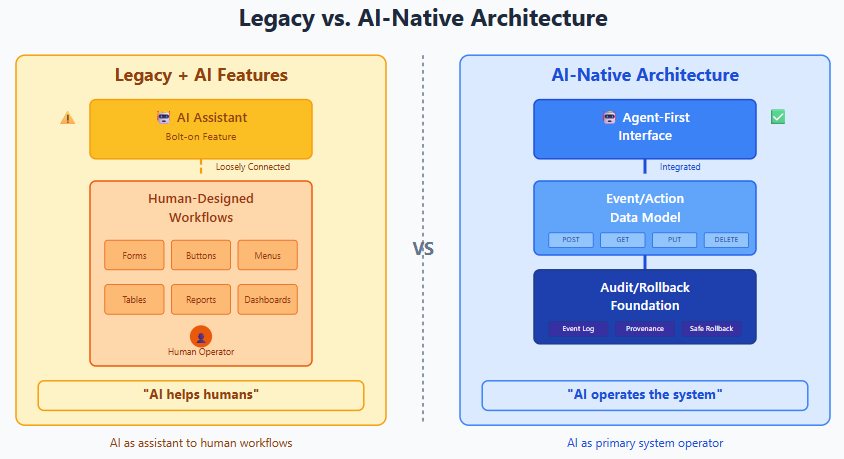

The Real Threat: AI-Native Insurgents

The actual threat to existing software companies doesn't come from enterprises building their own tools—it comes from new companies building AI-native alternatives with fundamentally superior architectures.

Consider the difference between legacy software adding AI features versus AI-native software built from the ground up around agent-driven workflows:

Legacy approach: Take an existing project management tool and add an AI assistant that can answer questions about project status or generate summaries. The AI is a feature bolted onto an existing architecture designed for human interaction.

AI-native approach: Build a project management system where AI agents are the primary interface, designed around event-driven data models that can predict bottlenecks, automatically allocate resources, escalate issues, and execute actions with full auditability and rollback capabilities. The software is designed to be operated by agents, not just assisted by them.

This architectural difference matters enormously. Legacy vendors face the challenge of retrofitting agent capabilities onto systems designed for human users, while AI-native companies can build agent-first from day one. It's the same dynamic that allowed Figma to disrupt Adobe—not by making design easier, but by building collaboration into the core architecture in ways that Adobe couldn't replicate by adding features.

These AI-native insurgents also have a distribution advantage. Rather than competing for user attention in the traditional software bazaar, they can focus on becoming the preferred endpoints for agent queries. They can optimize for programmatic access, clear action APIs, and reliable execution rather than human user experience.

The question for existing software vendors isn't whether they can add AI features—it's whether they can rebuild their architectures to be truly agent-native before insurgents capture their markets.

The New Moat Stack

For software companies to survive and thrive in an agent-mediated world, they need to develop new types of competitive advantages. The traditional moats—better features, superior user experience, or higher search rankings—are becoming less relevant when users primarily interact through agents.

The new moat stack for software consists of five layers:

1. Agent Reliability and Compliance

The ability to execute actions reliably with full auditability, provenance tracking, and safe rollback capabilities. When an agent makes a mistake or takes an unintended action, can the software provide a complete audit trail and safely reverse the change? This requires fundamental architectural changes that most legacy software wasn't designed for.

2. Data Advantage

Proprietary, compounding data that improves the software's capabilities over time, with clear legal rights to use that data for model training and improvement. The software that gets better through usage and provides unique insights unavailable elsewhere will maintain an advantage even in an agent-mediated world.

3. Distribution Power

Rather than relying on organic search or direct user acquisition, successful software companies will need to become trusted endpoints in agent ecosystems. This means clear action APIs, presence in agent marketplaces, integration with major productivity suites, and partnerships with systems integrators.

4. Workflow Control

For Systems of Record, this means controlling admin functions, policy enforcement, and permission systems. For Systems of Engagement, it means owning enough of the workflow that agents must interact with your software to complete user requests effectively.

5. Monetization Architecture

AI attach rates above 25% with stable or improving gross margins as inference costs decline. The ability to capture value from AI-enhanced workflows without seeing margins erode as AI becomes more capable and cheaper.

Companies that can build multiple layers of this moat stack will be much better positioned to maintain their value in an agent-driven world.

Go-to-Market After the Front Door Moved

The shift to agent-mediated software access has profound implications for how software companies acquire and retain customers. Traditional growth strategies built around organic search, content marketing, and direct user acquisition become less effective when agents intermediate the relationship.

The most immediate impact is on SEO-dependent businesses. If users increasingly ask agents to perform tasks rather than searching for tools to help them perform those tasks, organic search traffic to software websites will decline. This is already beginning to happen as AI overviews and agent responses satisfy user queries without driving clicks to underlying websites.

Companies that built their growth engines around content marketing and search optimization need to develop new channels:

Become a Trusted Endpoint: Rather than optimizing for human visitors, software companies need to optimize for agent queries. This means providing clear action APIs, comprehensive documentation for programmatic access, and reliability guarantees that agents can depend on.

Agent Marketplace Presence: Just as mobile apps needed to be discoverable in app stores, software tools need to be discoverable in agent ecosystems. This includes listings in marketplace directories, integration with major productivity suites, and partnerships with agent platform providers.

Partner Channel Renaissance: Systems integrators, consultants, and ecosystem partners become more important when direct user acquisition becomes harder. These channels can advocate for specific software solutions in enterprise decision-making processes that increasingly happen behind the scenes.

Brand and Community: When users don't interact directly with software as often, brand recognition and community advocacy become more valuable for maintaining preference and preventing commoditization.

The companies that successfully navigate this transition will be those that recognize the shift early and rebuild their growth strategies around agent-mediated distribution rather than direct user acquisition.

Pricing and Unit Economics in the Agent Era

The shift to agent-mediated software usage is also forcing a fundamental rethinking of pricing models. Traditional seat-based pricing assumes direct user engagement, but when agents perform tasks on behalf of users, the relationship between seats and value becomes tenuous.

Many software companies are experimenting with usage-based or outcome-based pricing: charging based on tasks completed, decisions automated, or measurable business outcomes achieved rather than the number of human users. This shift can work well when there's clear causality between the software's actions and measurable value—for example, charging based on customer support tickets resolved or sales cycles accelerated.

However, usage-based pricing in an AI world comes with significant risks. As AI becomes more capable and inference costs continue to decline, software companies need to ensure their unit economics improve rather than deteriorate. A pricing model that charges per AI action could become unsustainable if the cost of those actions drops faster than the price.

Successful companies are implementing several strategies to maintain healthy unit economics:

Price Fences: Creating tiers based on capability, speed, or service level rather than just usage volume. Premium tiers might offer real-time processing, human escalation, or enhanced compliance features.

Batch and Cache Optimization: Using technical architecture to reduce costs faster than prices decline, through intelligent caching, batch processing, and optimization of AI inference costs.

Value-Based Packaging: Focusing pricing on business outcomes and measurable value rather than technical metrics like API calls or processing time.

The companies that solve the pricing puzzle—capturing value from AI-enhanced capabilities while maintaining healthy margins as AI becomes cheaper—will have a significant advantage in the agent era.

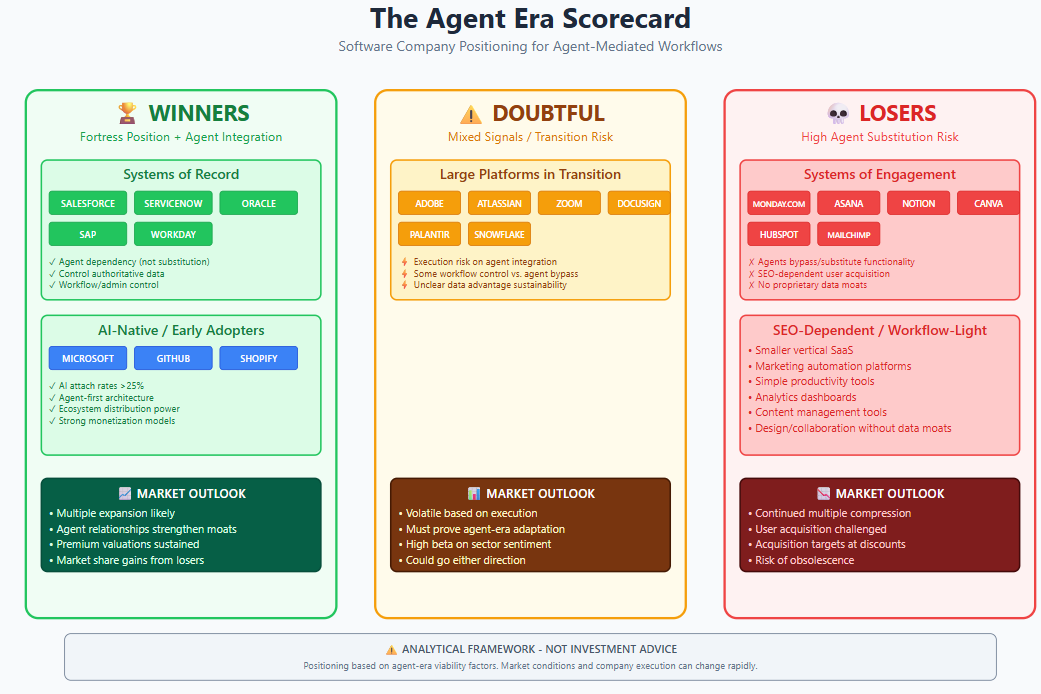

The Market's Harsh Verdict

Understanding this transition helps explain why the software market currently feels so unforgiving. When fundamental changes occur in how users access and interact with software, markets tend to reprice first and ask questions later. This creates a "guilty until proven innocent" dynamic where any software company that can't immediately demonstrate agent-era viability faces multiple compression regardless of current financial performance.

We're seeing this play out in real time. Companies that report solid growth and profitability but haven't articulated a clear agent strategy are being punished by investors who fear future obsolescence. Meanwhile, companies that can demonstrate early progress on agent integration or AI-native approaches are receiving premium valuations based on potential rather than current results.

This dynamic isn't irrational—it's how markets typically respond to platform shifts. During the transition from on-premise to cloud software, companies with strong on-premise businesses but unclear cloud strategies faced similar multiple compression. During the mobile transition, companies that couldn't demonstrate mobile-first approaches saw their valuations suffer despite strong desktop performance.

The harsh repricing reflects the market's assessment that when the front door moves, being late to recognize the shift is often fatal. Better to overreact to the transition than to underreact and miss it entirely.

The Innocence Test

Given this "guilty until proven innocent" market dynamic, what would it take for software companies to prove their viability in the agent era? Based on the analysis above, companies need to pass several specific tests to demonstrate they're adapting successfully:

Technical Execution Tests

Agent execution capability: Does the software enable agents to execute actions, not just generate drafts or summaries?

Audit and rollback systems: Are there comprehensive audit trails and safe rollback capabilities for agent actions?

Business Model Tests

AI attachment rates: Is AI monetization showing attachment rates above 25% and growing?

Inference cost trends: Are inference costs per task declining quarter over quarter while maintaining margins?

Distribution Tests

Non-SEO acquisition: Is the percentage of acquisition from non-SEO channels (partners, ecosystems, embedded distribution) increasing?

Retention stability: Is Net Revenue Retention remaining stable or improving independent of pricing changes?

Companies that can demonstrate progress on at least four of these six dimensions are likely to be viewed as "innocent" or "on probation" rather than "guilty." Companies showing strength in fewer than three areas remain at high risk of continued multiple compression.

This scorecard isn't perfect, but it provides a framework for evaluating which software companies are successfully adapting to the agent era versus those that are still fighting the last war.

Counterarguments and What Would Change My Mind

This analysis could be wrong in several ways, and it's important to articulate what evidence would cause me to update these views:

Organic discovery stabilizes: If direct software discovery and usage remains strong despite AI overviews and agent adoption, the threat to Systems of Engagement would be overstated.

Agent adoption plateaus: If users prefer dedicated applications for complex workflows and agent usage remains limited to simple queries, the intermediation risk would be lower than projected.

Multiple large software companies demonstrate sustained AI success: If several major software vendors show sustained AI attachment rates above 30% with stable or improving gross margins and growing non-SEO acquisition, it would suggest the adaptation challenge is more manageable than anticipated.

Regulatory or technical limitations: If privacy regulations, technical limitations, or security concerns significantly constrain agent capabilities, the timeline for disruption could be much longer.

I'll be watching specific datapoints each quarter: AI attachment rates across major software vendors, changes in organic search traffic to software websites, agent usage statistics from major platforms, and the financial performance of AI-native software companies versus legacy vendors adding AI features.

The goal isn't to be right about the specific timeline or mechanisms, but to correctly identify the directional shifts and their implications for software value creation and capture.

Playbooks for the Agent Era

For Software Leaders

The strategic imperatives for software company executives are becoming clearer:

Ship auditable agents immediately: Build and deploy agent capabilities that can execute actions with full audit trails and safe rollback mechanisms. Don't just add AI features—rebuild core workflows to be agent-native.

Diversify distribution channels: Reduce dependence on SEO and organic search by building presence in agent ecosystems, partner channels, and embedded distribution opportunities.

Invest in data moats: Secure legal rights to use customer data for model improvement and focus on creating data network effects that compound over time.

Rethink pricing models: Experiment with usage and outcome-based pricing while implementing technical and commercial guardrails to maintain healthy unit economics as AI costs decline.

For Investors

The investment implications of this analysis point toward a barbell strategy:

Overweight: Large platform companies and Systems of Record vendors that control critical data and can build agent capabilities on top of existing distribution advantages. Also favor AI-native companies that pass multiple innocence tests.

Underweight: Systems of Engagement vendors with high SEO dependence, seat-only pricing models, and limited progress on agent integration.

Pairs trading: Express views through relative positioning rather than outright short positions, given the difficulty of timing platform transitions precisely.

The key insight for investors is that this transition will likely create more extreme outcomes—bigger winners and more complete losers—rather than a gradual shift that affects all software companies equally.

The Arc Completes

The SAP story from thirty years ago provides a template for understanding today's transition. Just as SAP succeeded not by building the most customizable software but by standardizing business processes in ways that created switching costs and network effects, today's winners will be determined not by building the most intelligent AI but by controlling the standardized processes through which users access software functionality.

The front door to software has moved from direct user access to agent-mediated access. The companies that earn a place in that new flow, prove their value sticks in AI-enhanced workflows, and stop relying on yesterday's distribution channels will be the ones that thrive.

For some software companies, this transition represents an existential threat. For others, it's the foundation for building even stronger competitive positions. The difference will be determined by how quickly and effectively they can adapt their architectures, business models, and distribution strategies to a world where agents, not humans, are increasingly the primary interface to software.

The standardization is happening again, but this time it's not business processes being standardized—it's the process of accessing software itself. The companies that recognize this shift and position themselves as trusted endpoints in the new agent-mediated ecosystem will capture disproportionate value. Those that continue to optimize for direct human interaction risk being relegated to commodity status in the new software value chain.

The front door moved. The winners will be those who noticed first.

Disclaimer:

The content does not constitute any kind of investment or financial advice. Kindly reach out to your advisor for any investment-related advice. Please refer to the tab “Legal | Disclaimer” to read the complete disclaimer.

The front door moving to AI agents feels like the biggest software distribution shift since the cloud. If you’re not agent-native, you’re already on the clock.