TSMC 3Q25 Earnings: The Sandbagging Monopolist

How TSMC turned conservative guidance into a weapon of dominance

TL;DR:

TSMC’s “weak” guidance is a power play: By consistently sandbagging expectations and then beating them, TSMC turns conservatism into a weapon — reinforcing trust while concealing its true dominance.

Monopoly in disguise: With sub-7nm chip production effectively monopolized, customers like Apple and Nvidia lock in years of capacity — paying 50% more per wafer just to stay in line.

Controlled scarcity fuels pricing power: Rather than balancing supply and demand, TSMC strategically keeps the “gap narrow,” sustaining tight capacity to amplify dependence and protect margins.

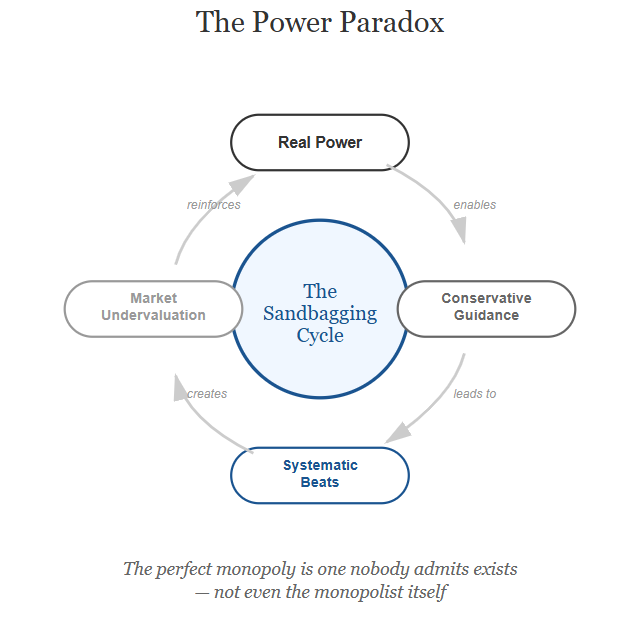

In 1985, Morris Chang sat in a Texas Instruments boardroom watching his company chase its own tail. TI would issue aggressive revenue guidance to signal strength to Wall Street, then inevitably miss those targets when reality refused to cooperate. Meanwhile, Japanese semiconductor companies did the opposite: they guided conservatively, then beat expectations quarter after quarter. Chang noticed what his American colleagues missed—the Japanese weren’t sandbagging because they were weak. They were sandbagging because they were strong enough to control the narrative.

When Chang left to found TSMC in 1987, he carried this lesson with him. Nearly four decades later, his company has perfected the art of managing expectations while building the most dominant position in semiconductor history.

The Pattern Emerges

In March 2025, TSMC CFO Wendell Huang delivered what sounded like terrible news. The company’s massive Arizona expansion—grown from a token $12 billion to an unprecedented $165 billion—would create “meaningful margin dilution.” Building fabs where construction costs run 4-5x higher than Taiwan would compress margins by 2-3% annually, maybe even 3-4% in later stages. Analysts dutifully built models showing TSMC’s industry-leading profitability eroding as geographic expansion took its toll.

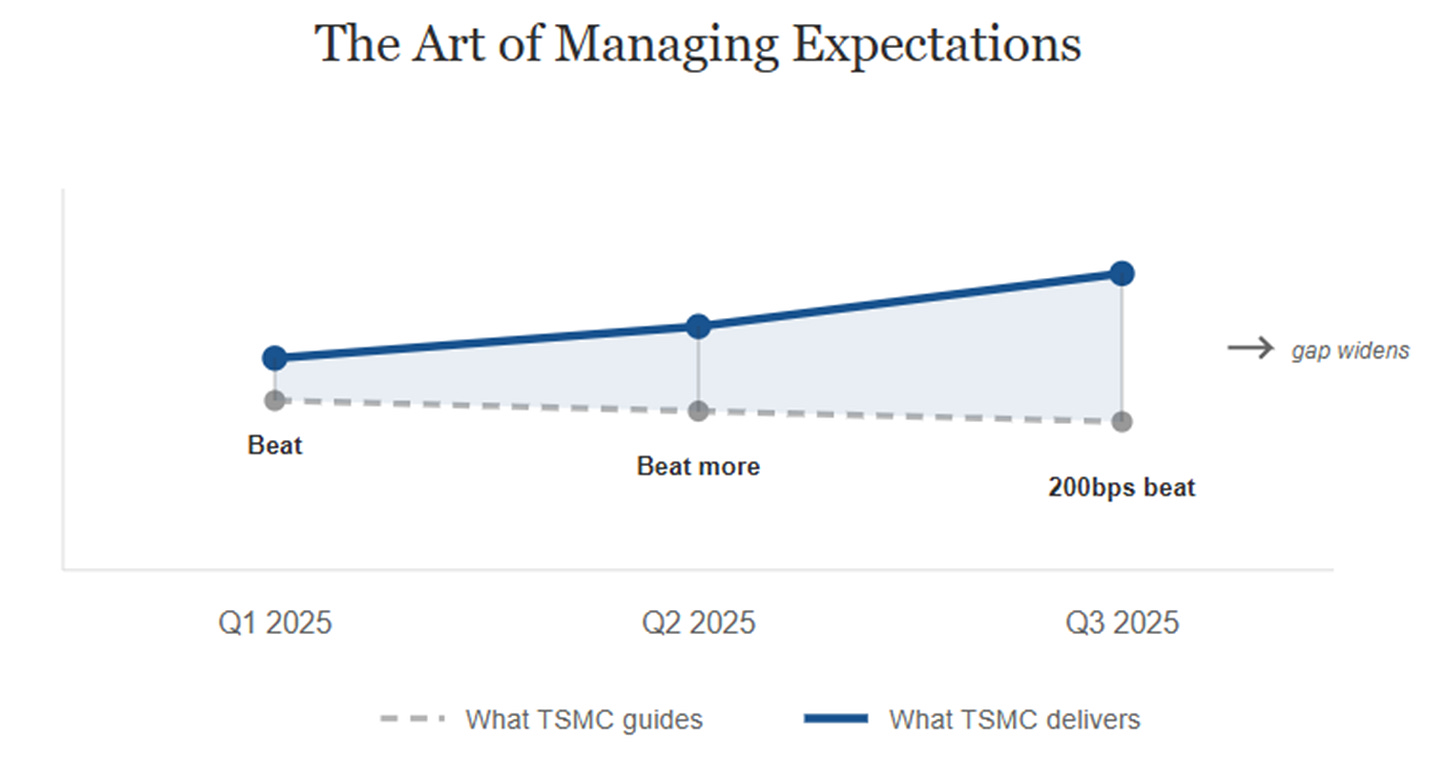

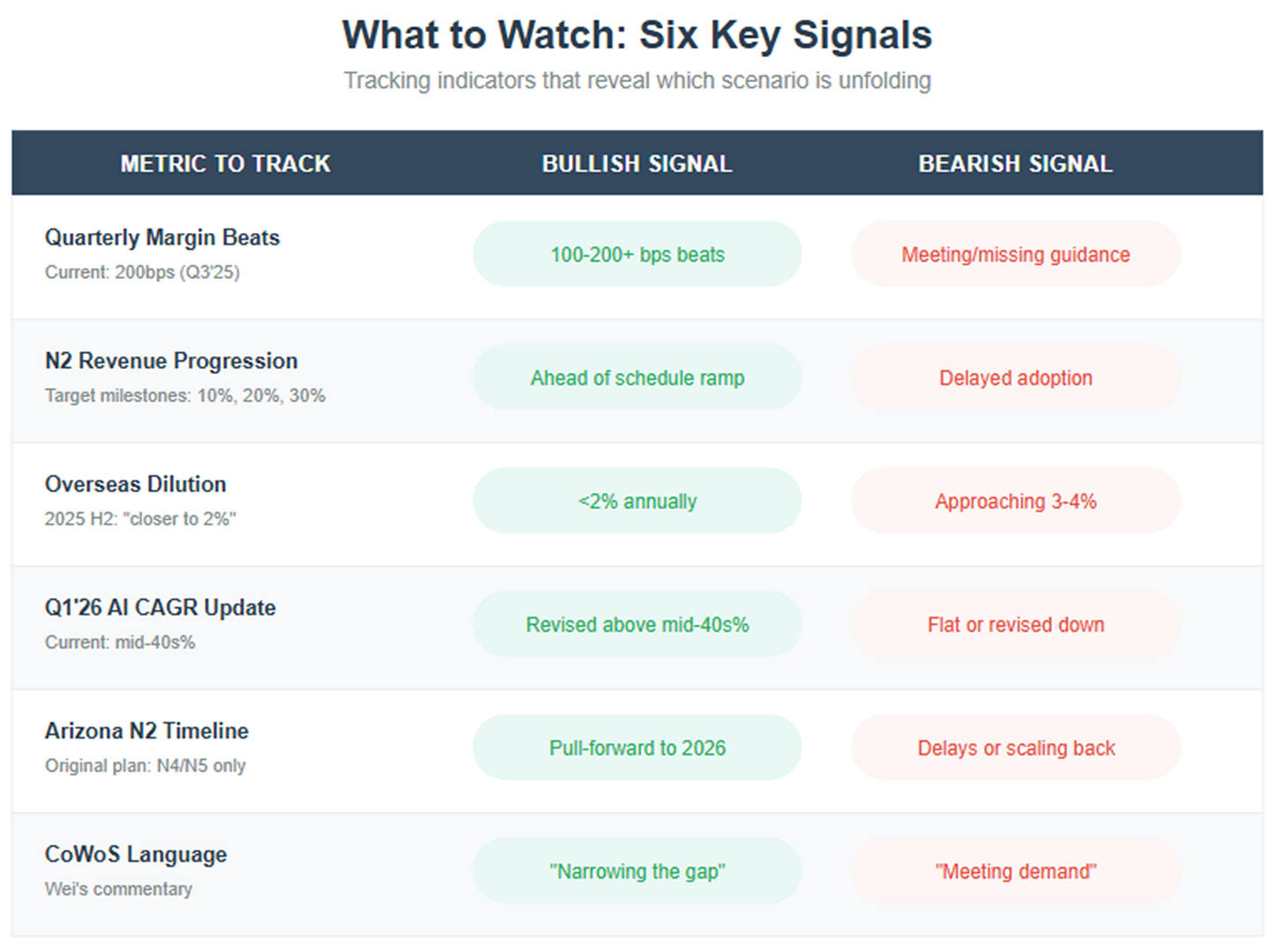

Three quarters later, a pattern has emerged that should be familiar to Chang. Q1 2025: margins beat guidance. Q2 2025: margins beat guidance. Q3 2025: margins beat guidance by 200 basis points. Each quarter, Huang’s warnings grow quieter. The 3-4% dilution became 2-3%, then “closer to 2%” for 2025. Meanwhile, gross margins printed at 59.5% in Q3 with guidance for 60% in Q4.

The most revealing moment came during Q3 earnings when CEO C.C. Wei was asked about AI demand. His response: “The AI demand actually continue to be very strong, more stronger than we thought three months ago.” That grammatical slip—”more stronger”—was the tell. This wasn’t carefully scripted investor relations speak. This was genuine surprise breaking through.

Why would a dominant company deliberately understate its strength?

The Monopoly That Dare Not Speak Its Name

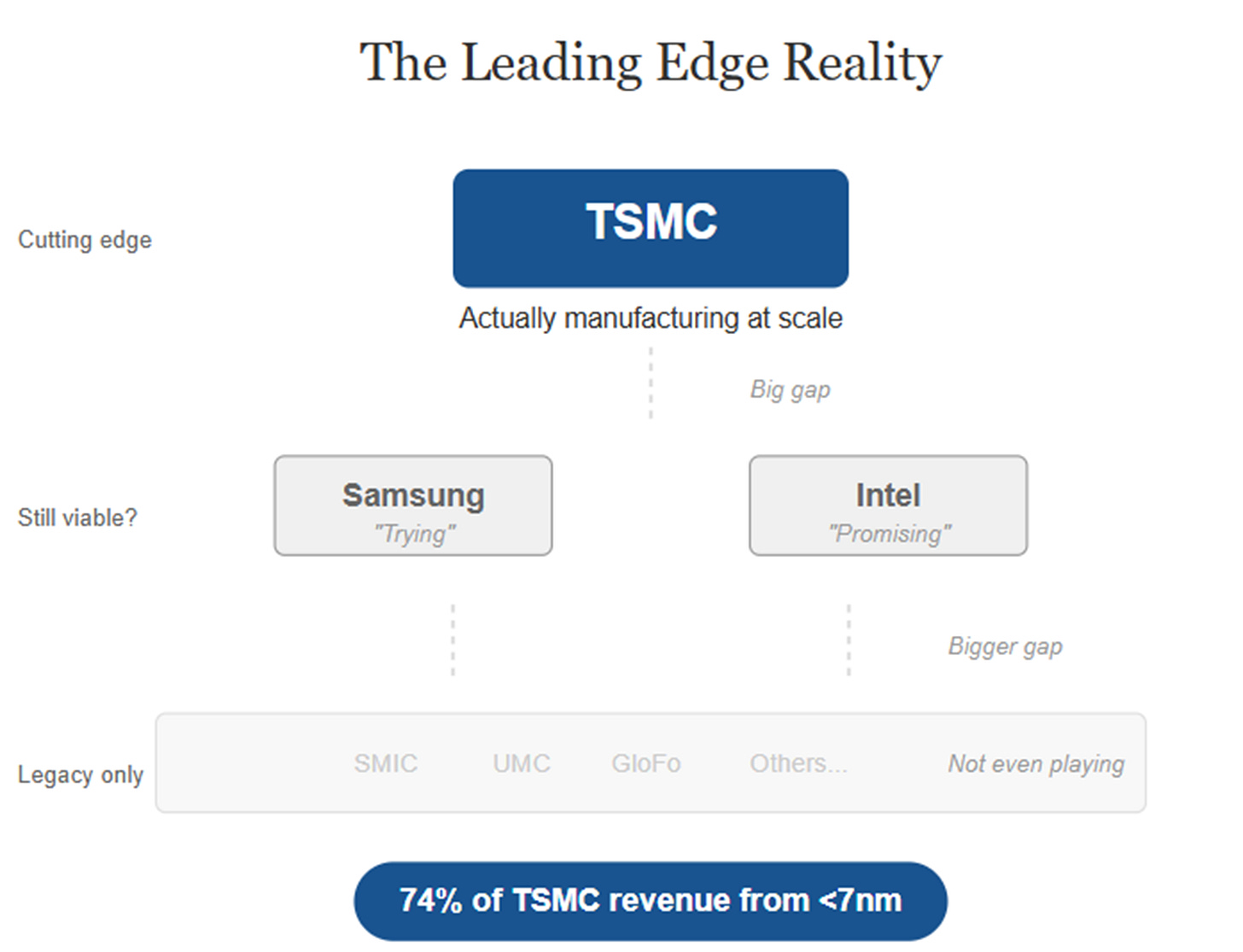

The semiconductor industry has a dirty secret: for cutting-edge chips that power AI systems, there is effectively one supplier. Samsung’s advanced nodes struggle with yields. Intel’s comeback remains perpetually next year. Every quarter that passes, TSMC’s stranglehold on sub-7nm production grows tighter.

This isn’t the typical technology lead that competitors eventually close. When Wei casually mentions that TSMC engages with customers “at least two to three years in advance,” he’s not describing forecasting. He’s describing what amounts to contractual servitude. Apple has already locked up half of TSMC’s initial 2nm capacity for 2026. Nvidia, AMD, and Broadcom have made similar long-term commitments because they understand a simple truth: there is nowhere else to go.

The numbers tell the story. A 3nm wafer costs around $20,000. The new 2nm wafers? $30,000. That’s a 50% price increase for one generation, and customers are competing to secure allocation. When buyers thank you for the privilege of paying 50% more, you’re not selling semiconductors—you’re controlling infrastructure.

This pricing power comes from demand dynamics unlike anything in semiconductor history.

The Demand Revolution

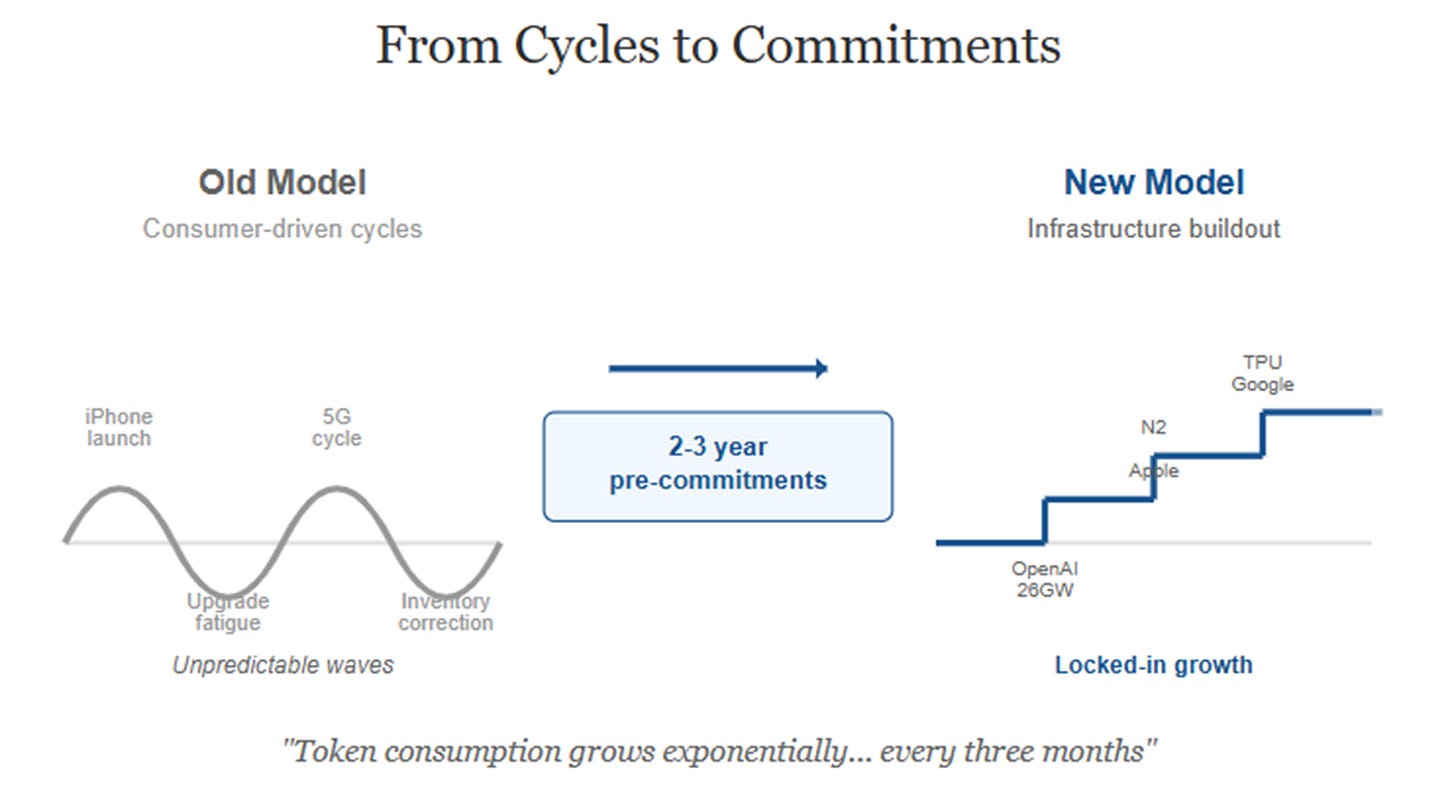

The traditional semiconductor cycle worked like this: consumer device sales drove chip demand, creating boom-bust cycles as phone upgrades accelerated or stalled. TSMC surfed these waves expertly, but they were still waves—external forces the company navigated rather than controlled.

Then came AI, and with it, a different kind of customer making a different kind of commitment. When OpenAI announces a 26-gigawatt AI infrastructure buildout through various partners, they’re not forecasting demand—they’re declaring dependency. Those 26 gigawatts translate to roughly 8-20 thousand wafer starts per month of incremental demand through 2030, stacked on top of existing commitments.

Wei explained the underlying dynamic: token consumption for AI inference is growing exponentially, “almost every three months it will be exponentially increased.” Yet TSMC can support this explosion with mere 45% revenue growth because each new node processes exponentially more tokens per dollar. It’s a virtuous cycle where customers get more compute per dollar even as TSMC charges more per wafer.

This is why Wei’s “more stronger” slip matters. Even TSMC, with its cultural commitment to conservative guidance, can’t hide its surprise at the demand trajectory.

When customers pre-commit years of demand at any price, traditional forecasting breaks. Which brings us to TSMC’s most elegant strategic move.

The Art of Controlled Scarcity

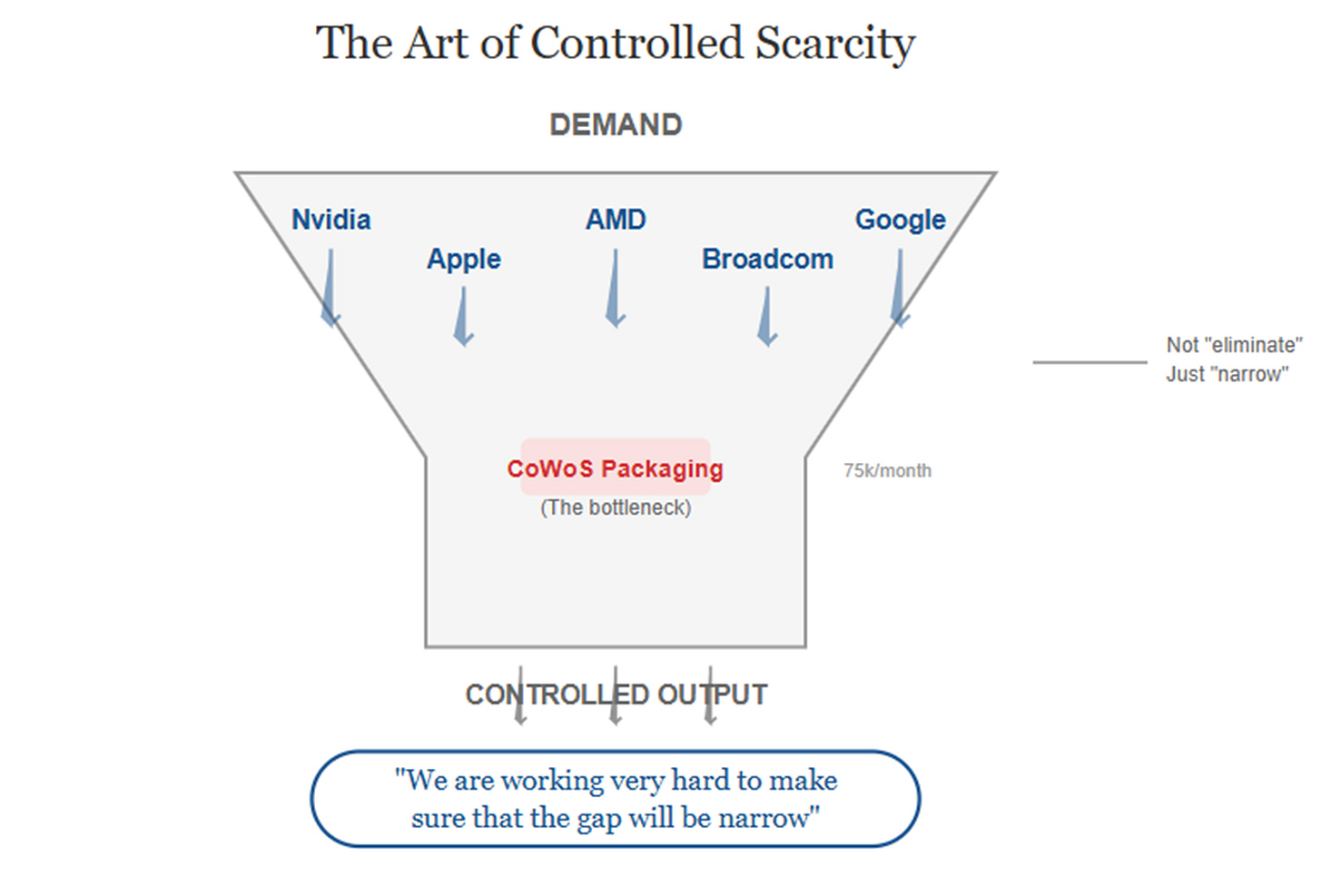

During the Q3 call, Wei chose his words carefully when describing capacity plans: “We are working very hard to make sure that the gap will be narrow.” Not “balance supply and demand.” Not “meet customer needs.” Just “narrow the gap.”

This is controlled scarcity as business strategy. TSMC could, theoretically, build capacity faster. They have the capital, the technology, the customer commitments. But why would they? Every quarter of shortage is another quarter of pricing power, another quarter where customers deepen their dependence.

The advanced packaging bottleneck illustrates this perfectly. CoWoS packaging capacity was just 13,000 wafers per month in 2023. Despite frantic expansion—targeting 75,000 by late 2025—demand still exceeds supply. Nvidia alone consumes 60% of available capacity. This constraint doesn’t hurt TSMC; it helps them. When customers can’t get enough chips packaged, they pre-commit further into the future, lock in longer agreements, accept higher prices.

Even the Arizona expansion, pitched as a costly geographic diversification, is really about maintaining leverage. By bringing a mysterious “large OSAT partner” to build packaging capacity that comes online before TSMC’s own facilities, they’re adding just enough capacity to keep customers hopeful while maintaining the fundamental scarcity.

This strategic positioning creates three possible futures.

Three Futures, One Pattern

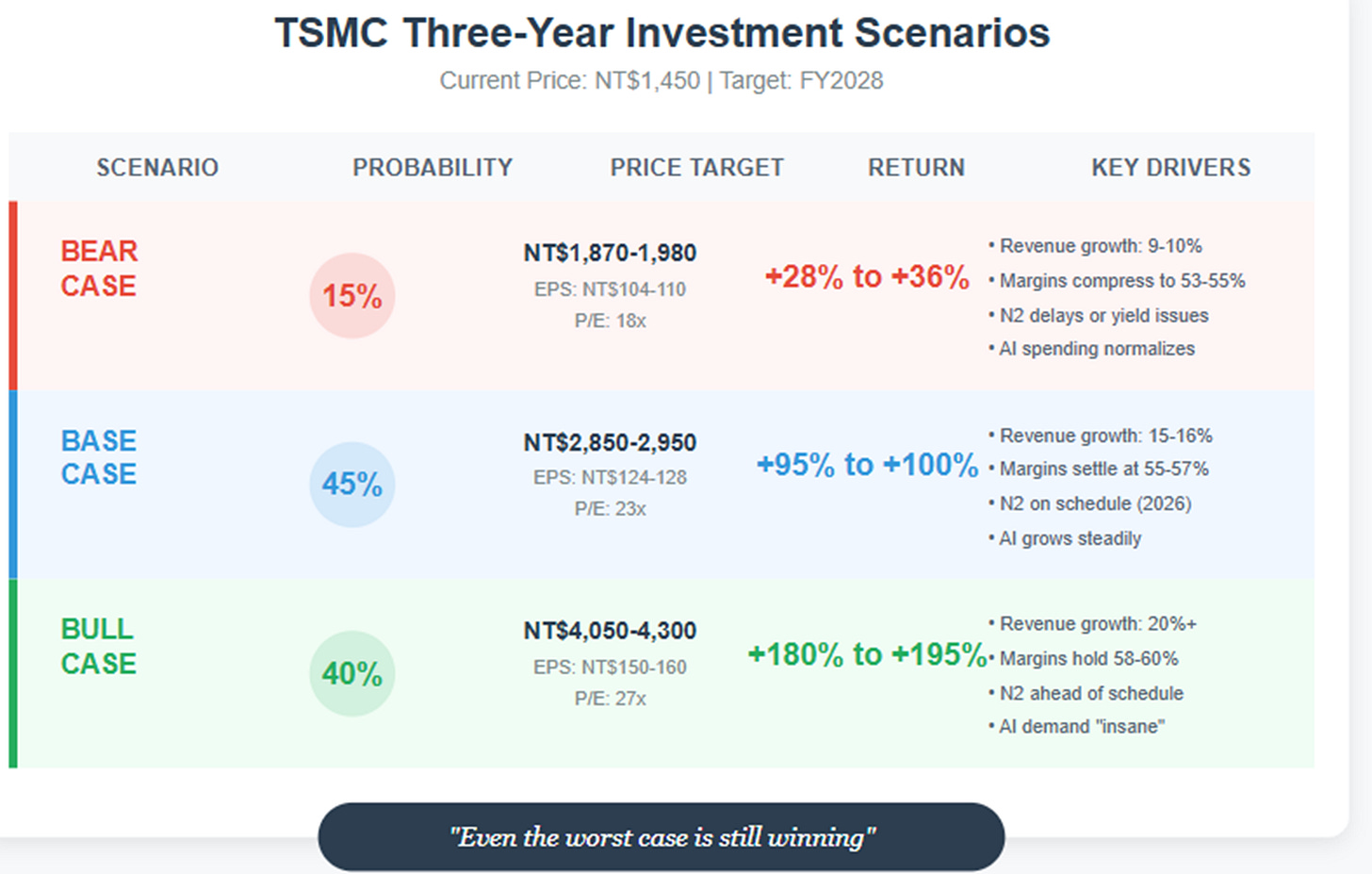

The base case is that TSMC’s sandbagging continues working exactly as designed. AI demand stays robust but rational, growing at “merely” 40% annually. TSMC’s margins “compress” to the mid-50s as overseas fabs ramp, giving Huang his warned dilution to point at. The company grows revenue 15-16% annually while claiming hardship about geographic expansion costs. The stock doubles over three years as the market slowly realizes 55% margins for a monopoly infrastructure provider is actually incredible. This is Chang’s playbook executing flawlessly.

The bull case is that even TSMC can’t hide the boom. AI demand breaks all models as every enterprise realizes they need their own infrastructure. The packaging constraints that seemed clever become genuine bottlenecks TSMC scrambles to address. Margins stay near 60% not because of currency effects but because customers bid up wafer prices in desperation. Revenue grows 20%+ as pricing power overwhelms any geographic cost penalty. The stock triples as the market reprices TSMC as the AWS of atoms.

The bear case—and this is where it gets interesting—is that the sandbagging finally comes true. AI spending normalizes as enterprises focus on making existing infrastructure efficient. The 2-3% margin dilution proves real as Arizona struggles and currency tailwinds reverse. Margins compress to the 53-55% range Huang has been warning about. Yet even here, TSMC grows revenue 10% annually and maintains 50%+ margins while controlling the future of computing. The stock still rises 30% because even the bear case describes an incredibly profitable monopoly.

What matters isn’t which scenario plays out, but what the pattern reveals.

The Chang Doctrine Lives

Strong companies guide weak because they can afford to be wrong. If TSMC says margins will compress and they don’t, everyone’s happy. If they say margins will expand and they don’t, trust erodes. By systematically underselling their resilience quarter after quarter, TSMC has trained the market to expect disappointment that never arrives.

This is the ultimate power flex: being so dominant you must pretend to struggle. Every warning about Arizona costs diluting margins is really a signal that customers are so desperate they’ll pay premiums that offset 4-5x construction costs. Every cautious guidance is really evidence that demand visibility extends so far into the future that surprises can only be positive.

The market prices TSMC like a cyclical semiconductor company because TSMC guides like a cyclical semiconductor company. That this is happening while they operate as monopoly infrastructure is the point. The perfect monopoly is one nobody admits exists—not competitors who might try harder, not regulators who might intervene, not even the monopolist itself.

Morris Chang understood in 1985 what Silicon Valley still struggles with: true power doesn’t need to announce itself. It demonstrates itself quietly, quarter after quarter, beat after beat, while claiming each victory was harder than expected.

The question isn’t whether TSMC will maintain its dominance. It’s whether the market will ever fully price in what that dominance means. As long as TSMC keeps sandbagging and the market keeps believing, the answer is probably not.

And that’s exactly how Chang would want it.

Disclaimer:

The content does not constitute any kind of investment or financial advice. Kindly reach out to your advisor for any investment-related advice. Please refer to the tab “Legal | Disclaimer” to read the complete disclaimer.