Uber 4Q25: Great Numbers, Mispriced Narrative

The selloff wasn’t about guidance, it was about robotaxis. And Uber’s own data just weakened the bear case.

TL;DR:

Uber printed strong growth and cash flow, but the market remains concerned about AV displacement fear.

AV fleets face a brutal utilization problem, and Uber’s platform improves utilization meaningfully.

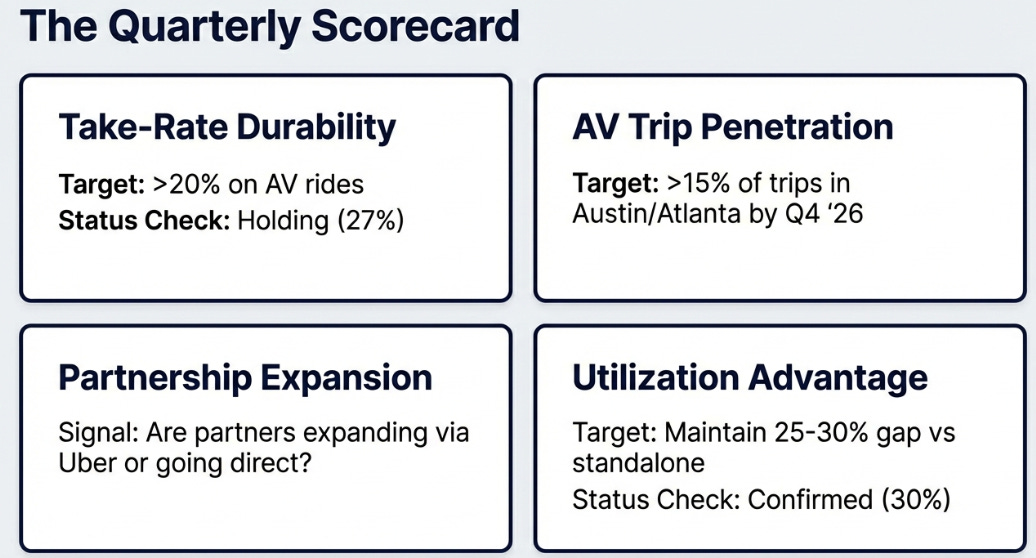

The next 18 months are about one metric: take-rate durability on autonomous rides.

The Utilization Inversion

Uber reported strong fourth-quarter earnings earlier in the week, $54 billion in gross bookings, up 22%; $2.8 billion in free cash flow, up 65%, and the stock fell 7%. The stated reason was a slight earnings guidance miss driven entirely by a UK tax accounting change with zero economic impact. The real reason is that the market still doesn’t know what Uber is worth in a world where cars drive themselves.

This is a strange place to be for a company that just generated $9.8 billion in annual free cash flow.

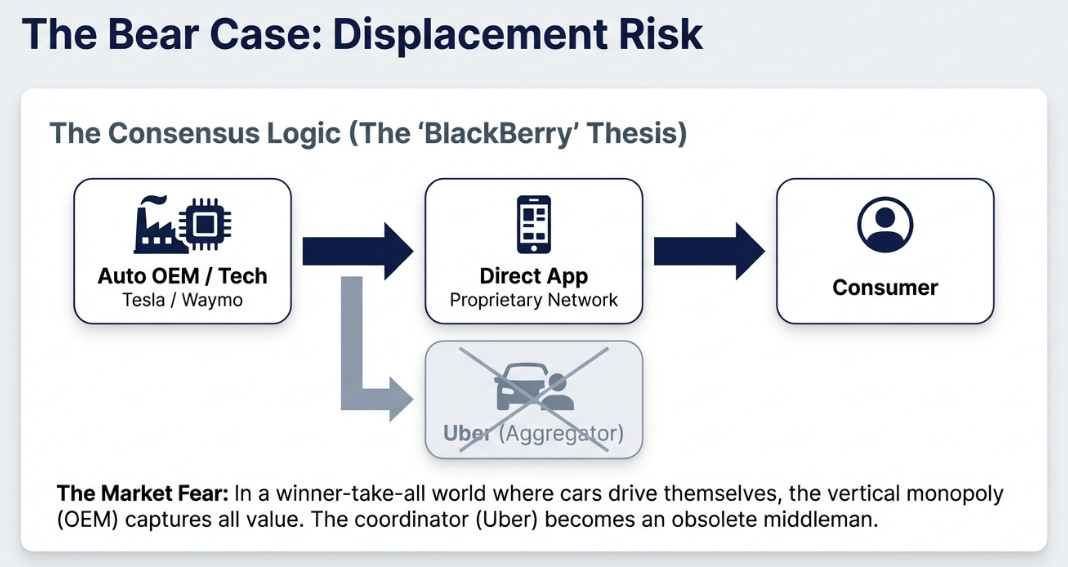

The autonomous vehicle overhang has haunted Uber’s valuation for years. The logic seems airtight: Waymo and Tesla will build robotaxi networks that bypass Uber, eliminating the need for a platform that connects riders to drivers once there are no drivers to connect. Uber becomes BlackBerry, a coordinator rendered obsolete when the thing being coordinated changes.

Buried in Uber’s earnings materials, however, was a data point that flips this logic: autonomous vehicles operating on Uber’s platform complete 30% more trips per vehicle per day than standalone deployments and deliver 25% faster pickup times than direct-to-consumer operations in San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Phoenix.

That’s not a small difference. It’s the difference between a working business model and a very expensive fleet of depreciating assets.

The Hidden Constraint

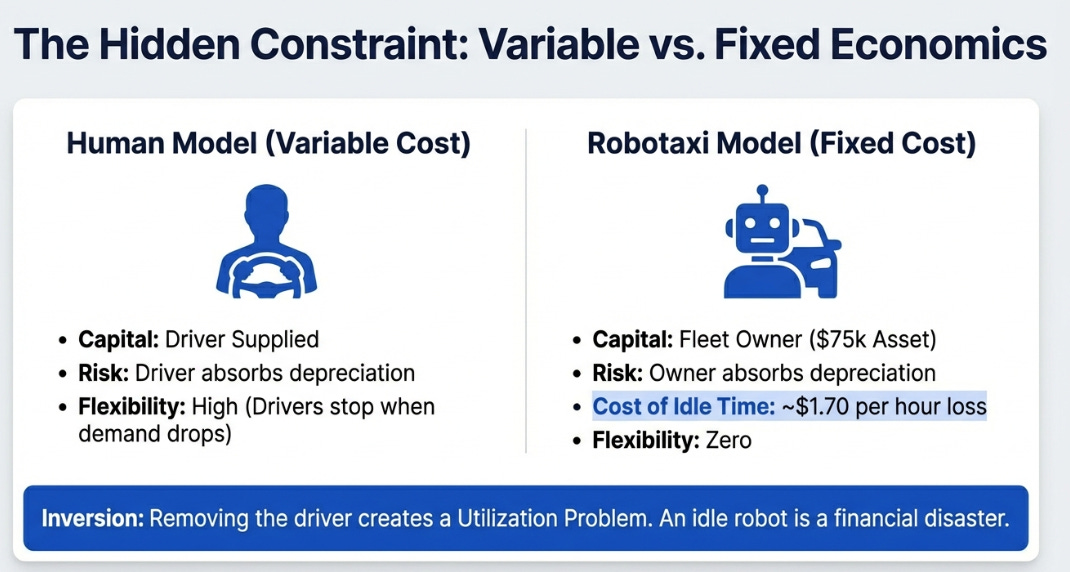

Start with what everyone knows: autonomous vehicles eliminate driver costs, which represent roughly 70% of a ride-hailing fare. This has always been framed as Uber’s problem, remove the driver, remove Uber’s value proposition.

But removing the driver doesn’t just eliminate a cost. It fundamentally changes the business model.

A human-driven Uber operates on variable cost. Drivers supply their own capital (the car), absorb the depreciation risk, and turn on the app when they want to earn. Uber’s capital intensity is near zero. When demand drops, drivers stop driving. When demand spikes, more drivers appear. The cost structure flexes with utilization.

A robotaxi operates on fixed cost. Someone, whether it’s Tesla, Waymo, or a fleet operator, owns a $50,000 to $100,000 asset that depreciates whether it’s moving or not. That asset needs insurance, charging infrastructure, cleaning, maintenance, and remote monitoring. Unlike human drivers, it can’t decide to take Tuesday off because demand is slow.

This creates what might be called the utilization problem: an autonomous vehicle sitting idle is a financial disaster. At $75,000 per vehicle and a five-year lifespan, every hour not generating revenue is roughly $1.70 in pure depreciation loss, plus ongoing operational costs. The math only works if the vehicle operates 16-20 hours per day at high productivity.

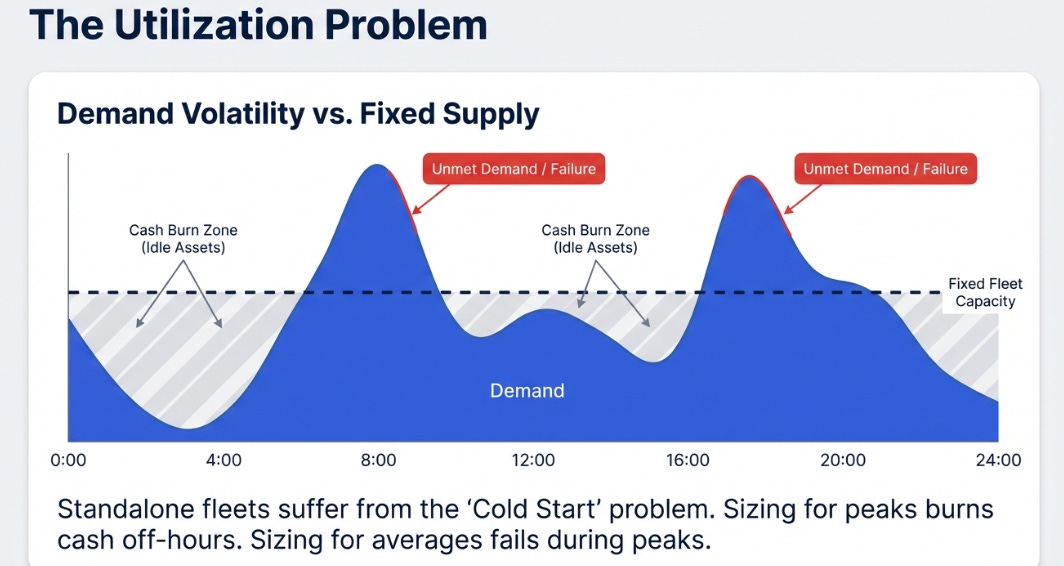

But cities don’t provide steady demand. Morning commutes, evening surges, weekend patterns, airport waves, weather disruptions, concerts, demand spikes and crashes throughout the day and week. A fleet sized for peak demand burns cash during off-peak. A fleet sized for average demand fails during peaks, destroying customer trust.

This is why Uber’s 30% utilization advantage matters. It’s not a nice-to-have. It’s the entire profit equation.

The Cold Start Economics

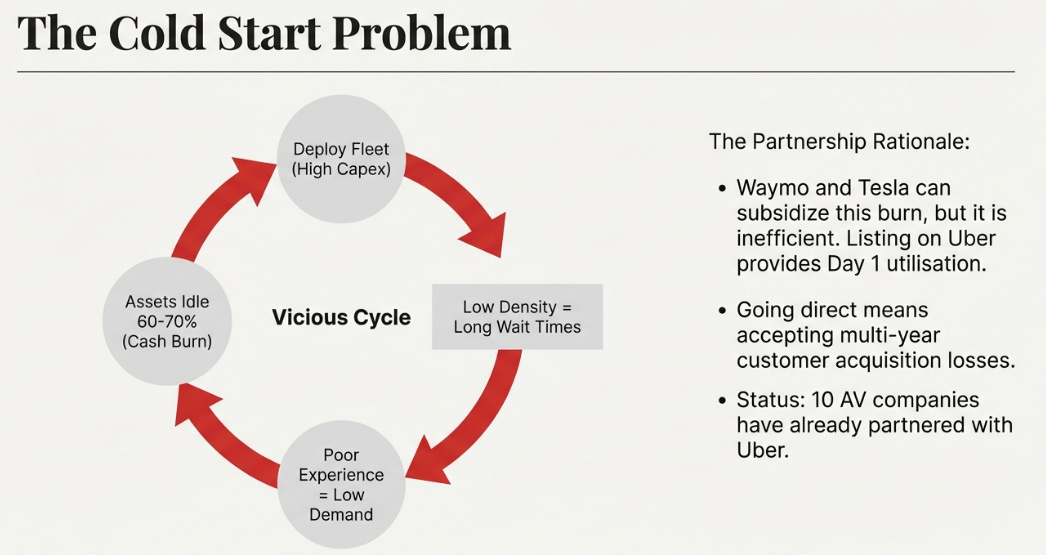

Here’s what the duopoly thesis misses: deploying autonomous vehicles profitably requires solving a chicken-and-egg problem that looks unsolvable without an existing demand base.

To offer reliable service, wait times under five minutes, consistent availability, you need vehicle density. But deploying hundreds of vehicles in a city without guaranteed demand means accepting terrible utilization until you’ve built consumer awareness and habit. That interim period involves burning millions per month while your $75,000 assets sit idle 60-70% of the time.

Waymo has Alphabet’s balance sheet to subsidize this. They can lose money for years building the habit loop. Tesla has similar resources and a brand advantage. But even for them, the question is economic efficiency: why burn cash on customer acquisition when someone else has already aggregated the demand?

This is why ten different autonomous vehicle companies have chosen to partner with Uber rather than go it alone. It’s not charity. It’s unit economics. Listing on Uber means day-one utilization at commercially viable levels. Going direct means multi-year customer acquisition losses.

The conventional narrative says Uber needs autonomous vehicle companies more than they need Uber. The utilization data suggests it’s the opposite.

The Three Equilibria

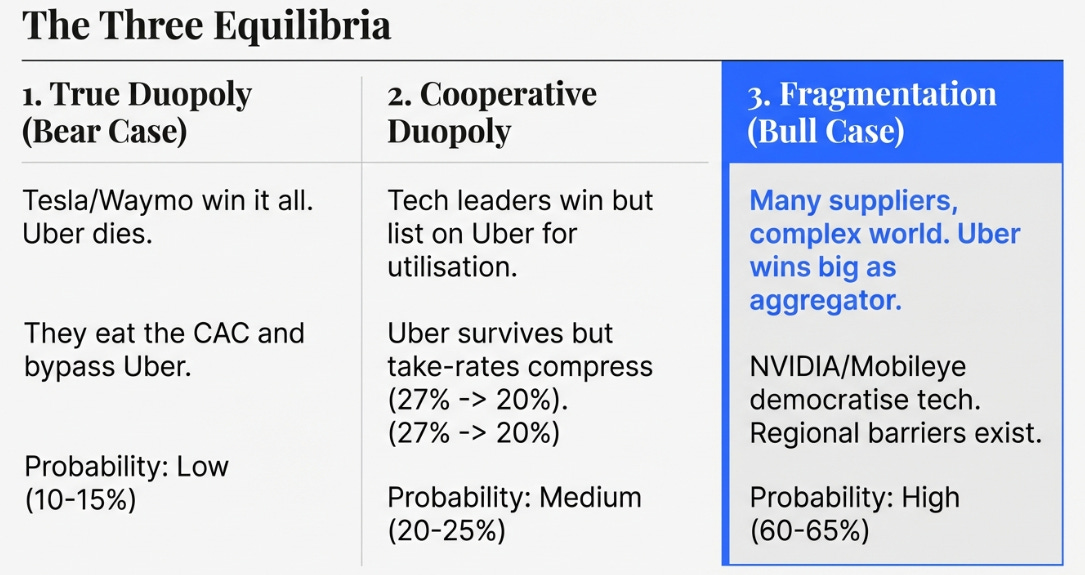

There are really only three ways this plays out, and only one of them eliminates Uber’s value.

The first is the true duopoly: Tesla and Waymo achieve such overwhelming technological and operational superiority that they can afford to build direct consumer relationships despite the utilization penalty. They scale to hundreds of thousands of vehicles, achieve consumer habit lock-in, and establish brand preference strong enough that users will wait longer or pay more for their specific service. In this world, Uber becomes a fallback option for human-driven rides and edge cases.

This requires not just solving Level 5 autonomy but also building charging infrastructure, cleaning operations, remote monitoring, incident response, and regulatory relationships in dozens of cities while sustaining years of negative unit economics. It’s possible, Alphabet and Tesla have the resources, but it’s the highest-cost path.

The second equilibrium is what might be called cooperative duopoly: the technology leaders (Waymo, Tesla) build the best stacks, but they list on Uber because the utilization advantage is too compelling to ignore. They compete on technology and service quality but accept that Uber owns the demand coordination layer. This is roughly where we are today with Waymo operating in Austin and Atlanta exclusively through Uber.

In this world, Uber survives but faces take-rate pressure. If there are only two suppliers with demonstrably superior technology, they have negotiating leverage. Uber’s take rate might compress from 27% toward 20% or below.

The third equilibrium, the one Uber is betting on, is multi-supplier fragmentation. This happens if:

Multiple technology providers reach “good enough” autonomy through modular stacks (NVIDIA, Mobileye)

Geographic fragmentation prevents global consolidation (China’s data sovereignty, Europe’s GDPR)

Operational complexity remains high (weather, edge cases, regulatory differences city-by-city)

Consumer preference stays with “one app that always works” over “best stack per trip type”

In this world, autonomous vehicle operators compete for access to Uber’s demand aggregation, just as hotels compete for placement on Booking.com despite having their own websites and loyalty programs. Uber’s take rate stays durable because it’s monetizing scarcity, not vehicle availability, but reliable utilization.

The Evidence for Fragmentation

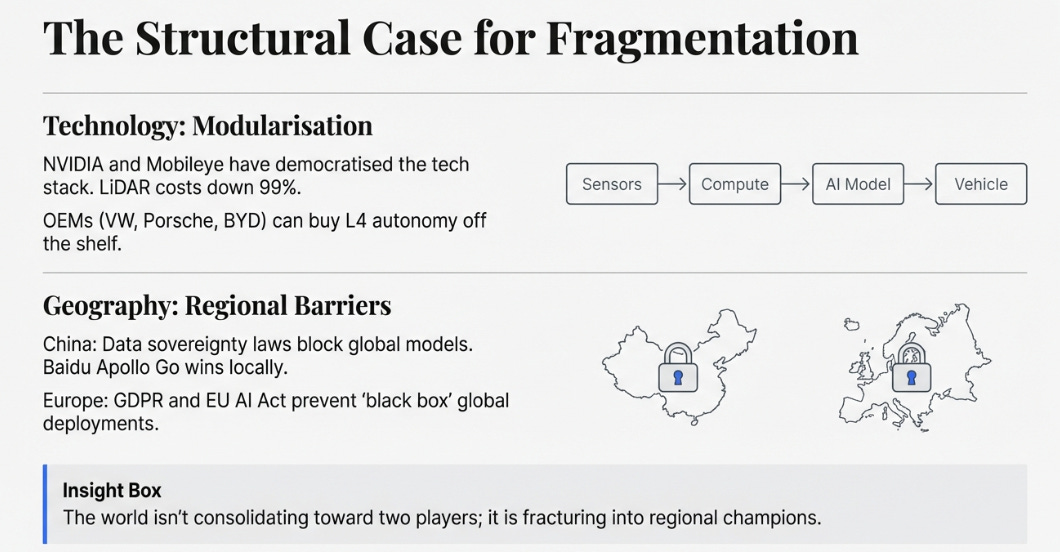

General Motors shut down Cruise in December 2024 after investing $16 billion. Ford abandoned Argo AI years earlier. These aren’t small players lacking resources, they’re the world’s largest automakers with century-long experience in vehicle manufacturing and deep pockets. Their explicit conclusion: full-stack autonomous development is uneconomic for all but a few companies.

What changed? NVIDIA and Mobileye made the core technology modular. NVIDIA’s DRIVE platform provides everything an OEM needs, sensors, compute, simulation software, to reach Level 4 autonomy. The customer list includes Toyota, General Motors, Mercedes, Hyundai, BYD, Li Auto, and XPeng. Mobileye has deployed SuperVision in over 300,000 vehicles across Volkswagen, Porsche, and Zeekr.

This isn’t hypothetical. LiDAR costs have fallen 99% from $75,000 per unit in 2015 to under $500 today. The time from “we want to build an AV” to “we have working Level 4” has compressed from a decade to 2-3 years for companies buying NVIDIA’s stack. The technological moat that justified a winner-take-all assumption is eroding.

Then there’s geography. China has issued over 16,000 autonomous vehicle test licenses across 30+ cities. Baidu’s Apollo Go operates more than 1,000 vehicles profitably in Wuhan. Data sovereignty laws require that sensor data and mapping information collected in China stay in China, effectively blocking foreign companies from training unified global models. Even if Waymo achieves technological dominance in the US, it can’t simply export that to China. The regulatory and political barriers are structural.

Europe presents similar constraints through GDPR and the EU AI Act, which classifies autonomous vehicles as high-risk systems requiring transparency that black-box neural networks struggle to provide. The global mobility market isn’t consolidating toward two players. It’s fracturing into regional champions.

Uber operates in 8,000+ US markets covering 95% of the population. Even if autonomous vehicles scale rapidly in dense, affluent showcase cities, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Phoenix, the notion that this immediately translates to Akron, Boise, or Chattanooga ignores both regulatory fragmentation and deployment economics. The market will remain hybrid for years, possibly decades. Hybrid markets favor coordinators who can route between human and autonomous supply based on availability, weather, and real-time conditions.

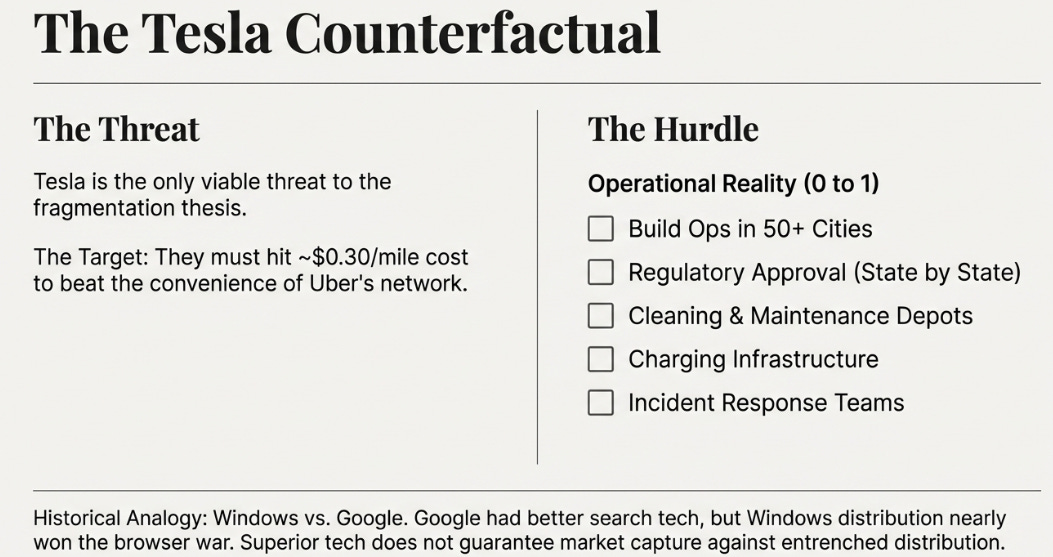

The Tesla Counterfactual

Tesla is the strongest challenge to this thesis. They’re currently operating 50-100 vehicles in Austin at a $4.20 flat fare, roughly half the cost of a typical Uber ride. If Tesla can deliver sustainable unit economics at that price point while scaling to tens of thousands of vehicles across major cities, the coordination layer advantage becomes irrelevant. Users will simply accept slightly longer wait times to pay half the price.

But this requires Tesla to solve problems that go beyond autonomous driving technology. At 100,000 vehicles, Tesla needs to finance $5 billion in capital before operational costs. They need city-by-city regulatory approval in 50+ major metros, each with different requirements and political dynamics. They need to build charging infrastructure, cleaning operations, and incident response capabilities that don’t scale automatically with fleet size.

Most critically, they need to solve the utilization problem in every new market from scratch. Uber’s existing demand density means that when a Waymo vehicle starts operating in Austin, it immediately achieves high utilization. Tesla’s standalone fleet must build consumer awareness while accepting underutilization until density reaches critical mass.

History offers a guide here, though not a perfect one. Google had superior search technology to Microsoft in the 1990s, but Microsoft’s Windows distribution nearly won the browser war. Netflix had better streaming technology than Blockbuster, but Blockbuster’s distribution delayed the transition for years. Superior technology alone doesn’t guarantee market capture when the incumbent has distribution and coordination advantages.

Tesla can win if they achieve such a radical cost advantage, say $0.30 per mile versus competitors at $0.80-1.00, that price overcomes everything else. That requires the vision-only approach to work flawlessly and scale globally while lidar-based systems remain expensive. Possible, but it’s betting on a specific technological outcome rather than playing the structure of the market.

The Platform Move

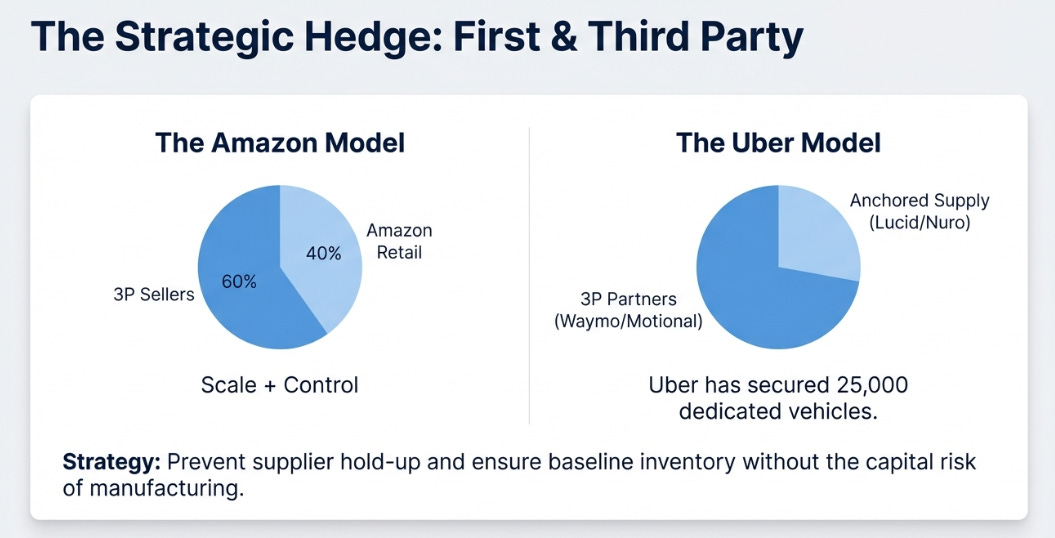

Even in a world where Uber wants to remain asset-light, the utilization problem creates pressure to guarantee supply reliability. This is why the Lucid and Nuro partnerships matter more than the headlines suggest.

Uber announced deals for 25,000 vehicles that will operate exclusively on Uber’s platform for their first years. This isn’t Uber building self-driving technology, it’s Uber securing anchored supply to prevent the scenario where a single autonomous provider gains enough market share to hold Uber hostage.

The Amazon parallel is instructive.

Amazon operates a massive third-party marketplace where 60% of units sold come from independent sellers. But Amazon also operates Amazon Retail, selling its own products that account for 40% of units. This dual model serves several purposes: it sets quality standards, provides baseline inventory when third parties have gaps, and, critically, it prevents any single supplier from gaining too much leverage.

Amazon uses data from third-party sellers to identify high-margin categories, then launches Amazon Basics products that compete directly. This sounds predatory until you realize it’s the only way to prevent supplier hold-up in a two-sided marketplace at scale.

Uber is moving toward a similar structure. Host multiple third-party autonomous fleets (Waymo, Cruise, Motional) while maintaining dedicated capacity that can’t be pulled off the platform. Learn operational intelligence from hosting Waymo, which routes generate best margins, which vehicle configurations maximize utilization, where demand is most predictable, then apply that to optimizing first-party deployment.

The capital requirements are manageable. Uber generated $9.8 billion in free cash flow last year with guidance toward $10+ billion in 2026. That cash generation enables minimum utilization guarantees to fleet partners, upfront insurance cost absorption during scaling, or balance sheet financing for purpose-built vehicles, none of which would be possible if Uber were still burning cash. The structure suggests Uber isn’t buying vehicles outright but securing exclusivity through commercial arrangements that keep the model asset-light while providing strategic control.

This isn’t Uber becoming a car company. It’s Uber ensuring it never becomes dependent on any single supplier.

The Operating System Question

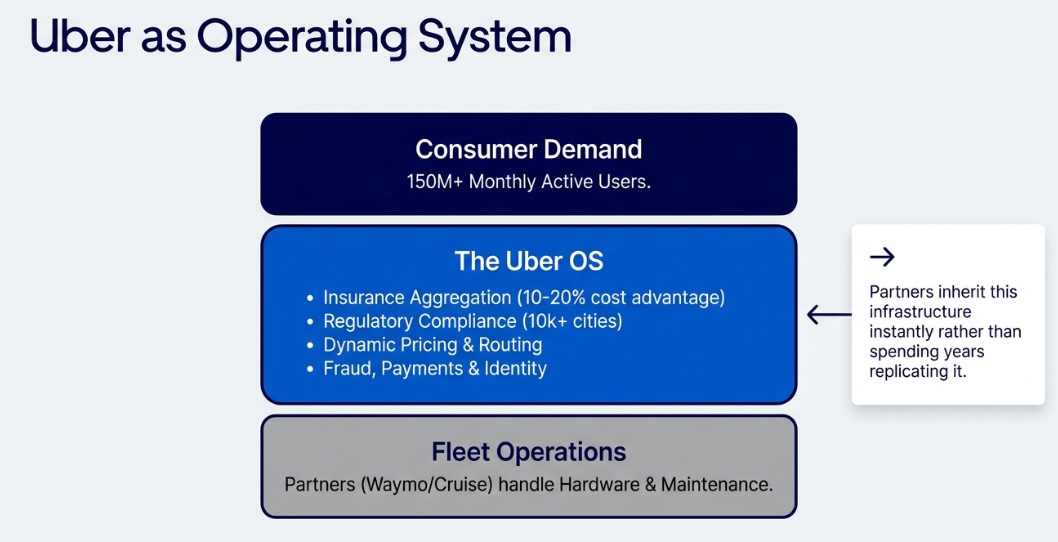

The debate over whether Uber is a platform or just a marketplace misses the point. The relevant question is: what specific functions does Uber perform that autonomous vehicle operators can’t easily replicate?

Insurance aggregation across millions of trips delivers 10-20% cost advantages versus a startup deploying 1,000 vehicles. Regulatory compliance infrastructure across 10,000+ cities means Uber already has permits, tax structures, and political relationships that take competitors years to build city-by-city. Dynamic pricing algorithms predict block-level demand 15 minutes before it materializes, enabling preemptive vehicle positioning that reduces wait times. Payment infrastructure handles millions of daily transactions across payment methods and currencies while preventing fraud. Trust and safety systems, background checks, real-time monitoring, incident response, cost billions to build and require constant operational investment.

These aren’t generic marketplace features. They’re specialized capabilities that create genuine lock-in. A fleet operator partnering with Uber inherits this infrastructure immediately rather than spending years and hundreds of millions replicating it.

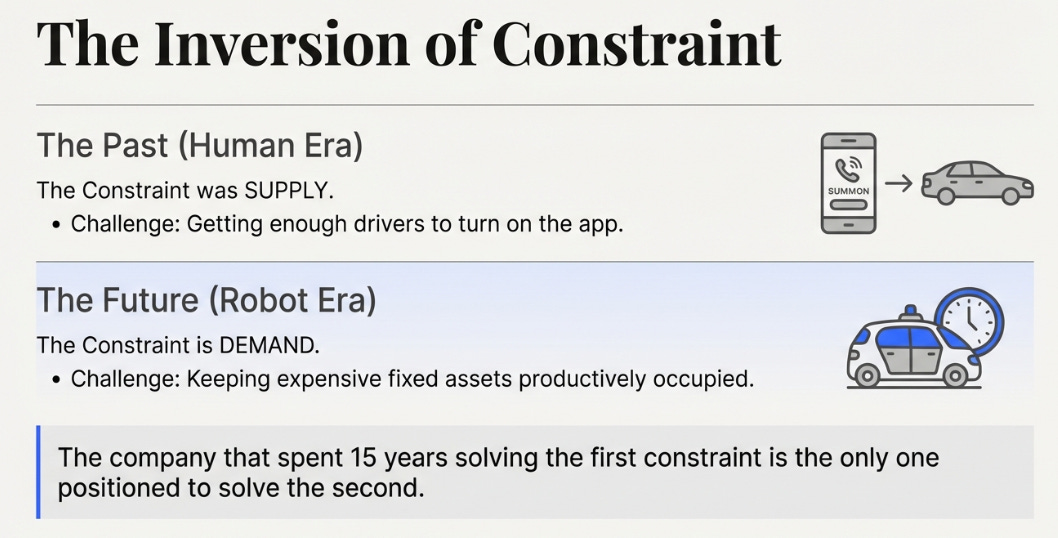

But the deeper point is about the resource constraint. In human ride-hailing, the constraint was driver supply, getting enough people to turn on the app. In autonomous mobility, the constraint is demand aggregation, ensuring expensive capital assets stay productively occupied.

The company that built its entire business solving the first constraint happens to be exactly the company best positioned for the second.

What It’s Worth

Current valuation: $74 per share, $153 billion market cap, 21x forward earnings.

The market is pricing Uber as if autonomous vehicles create a 50-60% probability of business model collapse over the next 5-7 years. This shows up in the multiple, mature platform businesses with strong cash generation and network effects typically trade at 25x+ earnings. Uber trades at 20x despite 20%+ EPS growth because investors are discounting future cash flows for displacement risk.

If the multi-supplier fragmentation world materializes, which the evidence suggests is more likely than duopoly, Uber’s coordination layer becomes more valuable, not less. Revenue grows at 15-18% annually as autonomous trips supplement rather than replace human-driven volume. EBITDA margins expand from 17% today toward 22% as driver incentive costs shift to utilization optimization across autonomous fleets. Free cash flow reaches $15-17 billion annually by 2028.

At 20x earnings on that cash flow generation, reflecting platform scarcity in a fragmented autonomous world, the equity is worth $150+ per share, or roughly $300+ billion in market cap.

If instead the world evolves toward cooperative duopoly where technology leaders list on Uber but extract better economics, revenue grows at 12-14% and take rates compress modestly from 27% toward 22-24%. Margins expand less, reaching 19% by 2028. Free cash flow hits $13-14 billion. At 16-18x, that’s $100 per share, or $210+ billion.

The bear case, true duopoly with direct distribution, requires Tesla and Waymo to both achieve technological dominance and choose to absorb customer acquisition costs and poor early utilization rather than list on Uber. Revenue growth slows to 8%, take rates compress toward 15-18%, and margins stall at 16%. At a discounted 12-14x multiple, that’s $50-65 per share.

The probabilities: 60-65% on fragmentation, 20-25% on cooperative duopoly, 10-15% on true duopoly.

The market appears to be pricing something closer to duopoly. We believe fragmentation is most likely. The gap is the opportunity.

The Pattern

This setup is familiar. In February 2022, Meta’s stock fell 26% in one day on fears that Apple’s privacy changes and TikTok’s format shift would destroy its advertising business. The stock ultimately fell 77% from peak. Then metrics proved that Meta could integrate Reels and rebuild targeting through AI, and the coordination layer, 10 million advertisers with no viable alternative at scale, remained intact. The stock recovered 547%.

In early 2023, ChatGPT appeared to threaten Google’s search dominance. The stock dropped $100 billion on fears that generative AI would make traditional search obsolete and destroy margins. Search revenue grew 12.5% year-over-year anyway as Google integrated AI Overviews faster than OpenAI could build distribution. The stock rallied 289%.

The pattern: markets confuse technology disruption with distribution collapse. They underweight coordination advantages, the difficulty of aggregating millions of advertisers or billions of search queries or hundreds of millions of ride requests. The re-rating comes when metrics prove the coordination layer can absorb the new technology rather than being displaced by it.

Uber’s utilization data is the first metric suggesting absorption rather than displacement. The quarterly scorecard over the next 18 months will tell us if that holds.

What to Watch

The thesis is falsifiable. The single most important metric is take rate on autonomous rides. If Uber maintains 25-27% platform fees while fleet operators earn attractive returns, the coordination layer captures value durably. If take rates compress toward 15-18%, suppliers have pricing power and the duopoly thesis gains credibility.

Secondary metrics:

Autonomous trip percentage in Austin and Atlanta (above 15% of local trips by Q4 2026 signals rapid adoption)

Partnership trajectory (Waymo expanding to more cities via Uber versus going direct)

Tesla’s Austin fleet size (staying under 2,000 vehicles supports fragmentation; reaching 10,000+ with regulatory approval supports duopoly)

Driver earnings in AV-heavy markets (maintaining premium versus national average means market expansion; sharp decline means cannibalization)

Utilization advantage persistence (25-30% maintained versus narrowing toward parity)

Current score: utilization advantage confirmed at 30%, take rate holding at 27%, partnerships expanding, driver earnings above average in Austin, Tesla at 50-100 vehicles. This leans 70% toward fragmentation, 30% toward base case.

The re-rating happens when the market shifts from viewing autonomous vehicles as displacement risk to viewing them as accelerant for Uber’s core business model. That shift requires consistent quarterly evidence that World C, multi-supplier fragmentation with Uber as coordinator, is materializing rather than World A duopoly.

The Inversion

Uber built a business by solving the problem of how to make human drivers productively busy. The constraint was supply, getting enough drivers on the road at the right times to meet demand.

Autonomous vehicles invert the constraint. Supply becomes abundant and capital-intensive. The scarce resource becomes demand aggregation, keeping expensive fixed assets productively occupied.

The company that spent 15 years solving “how do we find enough drivers?” happens to have built exactly the infrastructure needed to solve “how do we keep robots busy?”

That’s not guaranteed to work. If Tesla or Waymo achieve such overwhelming technological and cost advantages that users willingly accept the friction of a separate app and longer wait times, Uber’s coordination layer becomes less valuable. If regulatory approval happens faster than expected and deployment costs fall more than anticipated, vertical integration might beat the modular approach.

But the base case, the one the evidence currently supports, is that autonomy fragments rather than consolidates. Multiple technology providers reaching “good enough” via NVIDIA and Mobileye. Geographic barriers preventing global winners. Operational complexity remaining high. Consumer preference defaulting to “the app that always works.”

In that world, Uber doesn’t get disrupted. It gets promoted from ride coordinator to mobility infrastructure.

The market is pricing Kodak. The data suggests App Store.

The quarterly evidence over the next six quarters will tell us which movie we’re actually watching.

Disclaimer:

The content does not constitute any kind of investment or financial advice. Kindly reach out to your advisor for any investment-related advice. Please refer to the tab “Legal | Disclaimer” to read the complete disclaimer.