United Health 4Q25 Earnings: The Mean That Moved

Coding arbitrage is over, Optum Health has collapsed, and three decades of growth just ended

TL;DR

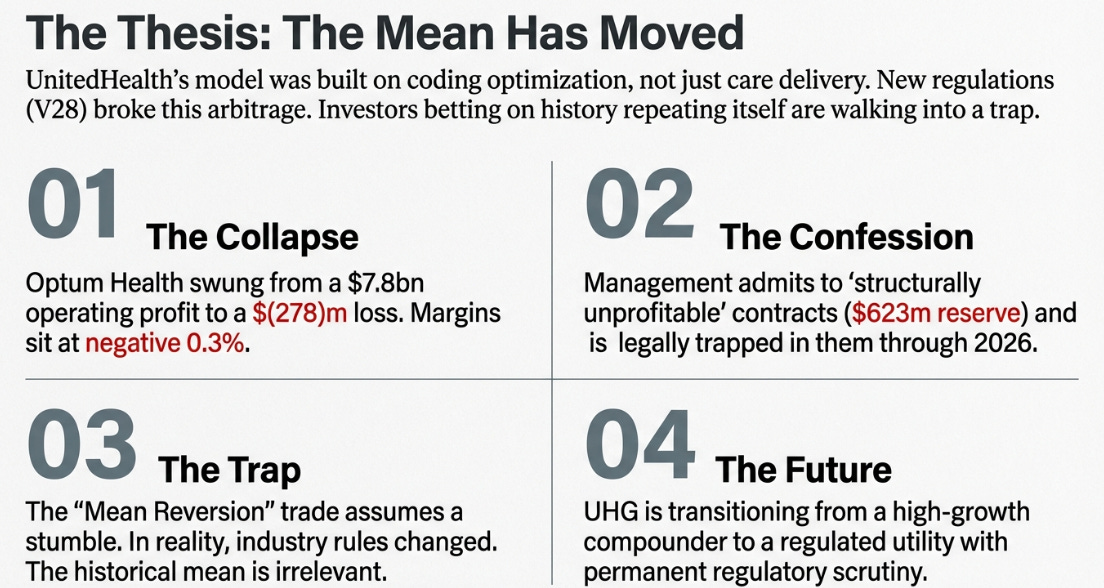

Optum Health imploded: a $278M operating loss and “structurally unprofitable” contracts expose a model built on coding optimization, not care delivery.

The regulatory mean has moved: V28 coding changes and a 0.09% 2027 MA rate hike permanently reset margins and growth.

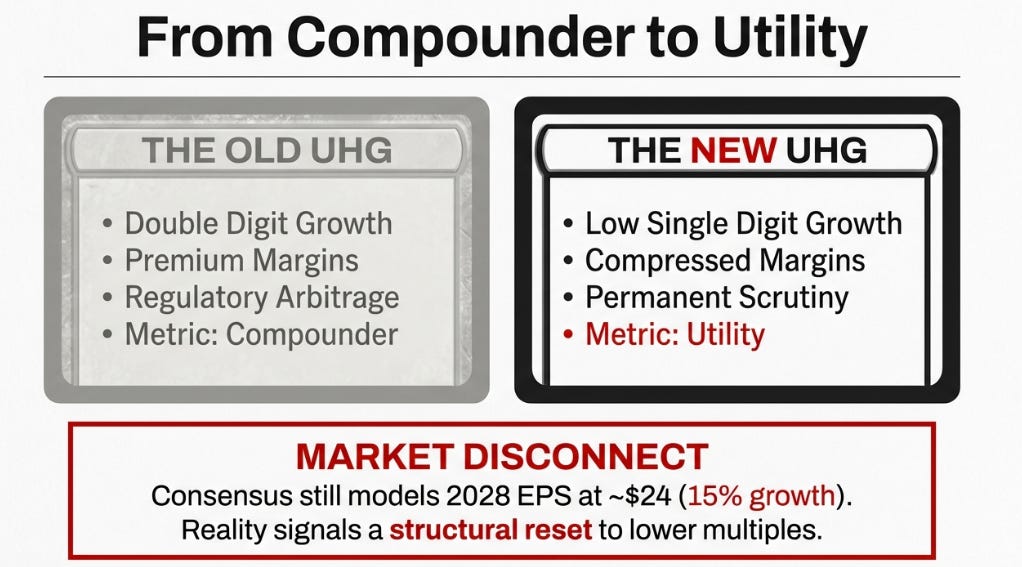

This isn’t a rebound setup: UnitedHealth looks less like Apple 2016 and more like IBM 2011, a transition from compounder to utility.

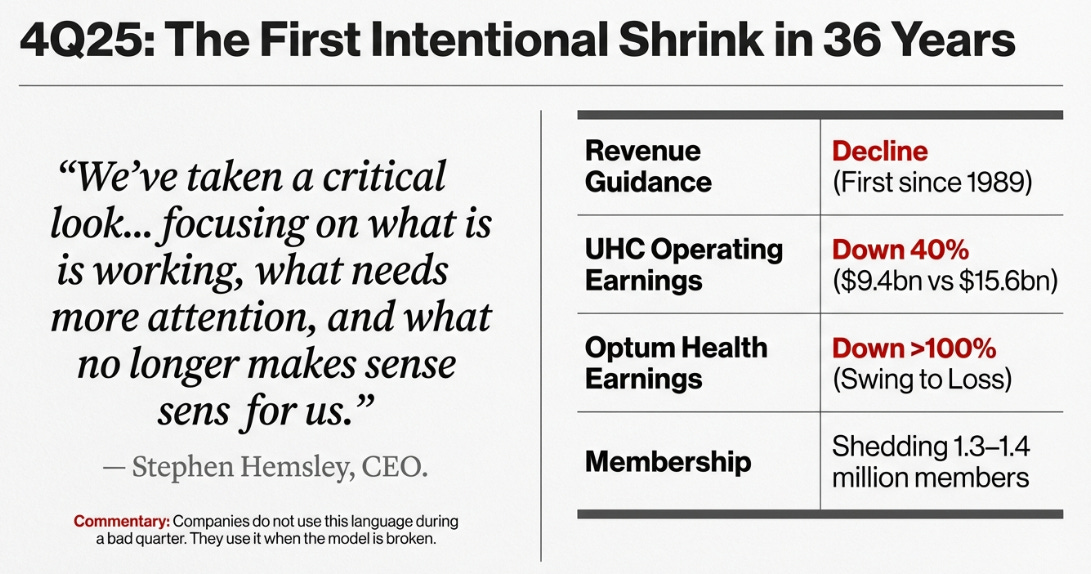

“We’ve taken a critical look across all our products and our US market positions, focusing on what is working, what needs more attention, and what no longer makes sense for us.” , Stephen Hemsley, CEO, UnitedHealth Group, 4Q25 Earnings Call

Companies don’t say this when they’re having a bad quarter. They say this when the model broke.

The Thesis, Confirmed

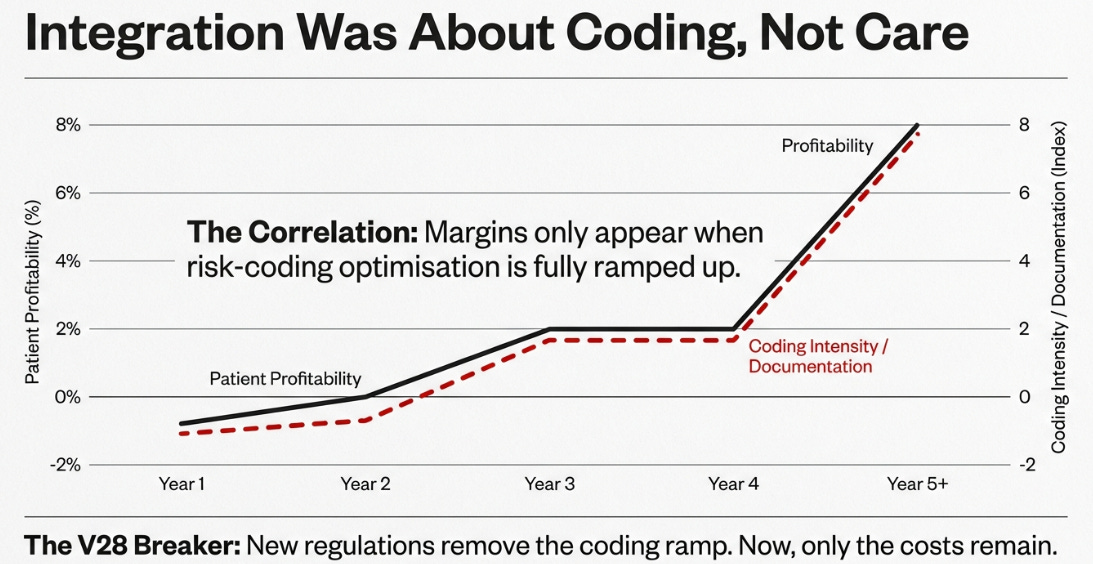

In July, after UnitedHealth’s second quarter results, I argued that the company’s celebrated integration wasn’t primarily about care delivery, it was about coding optimization. The Optum machine had been built to maximize Medicare risk adjustment payments through comprehensive diagnostic documentation, not to coordinate patient care.

In November, after third quarter results, I called it “The Cohort Confession.” Management had disclosed patient profitability by tenure: negative margins in years one and two, 2% margins in years three and four, and 8% margins in year five and beyond. The explanation offered was that care management takes time to produce results. The reality, I argued, was that this curve mapped to the timeline required to complete diagnostic documentation. It wasn’t a care management learning curve. It was an optimization timeline.

Fourth quarter 2025 didn’t challenge that thesis. It confirmed it, brutally.

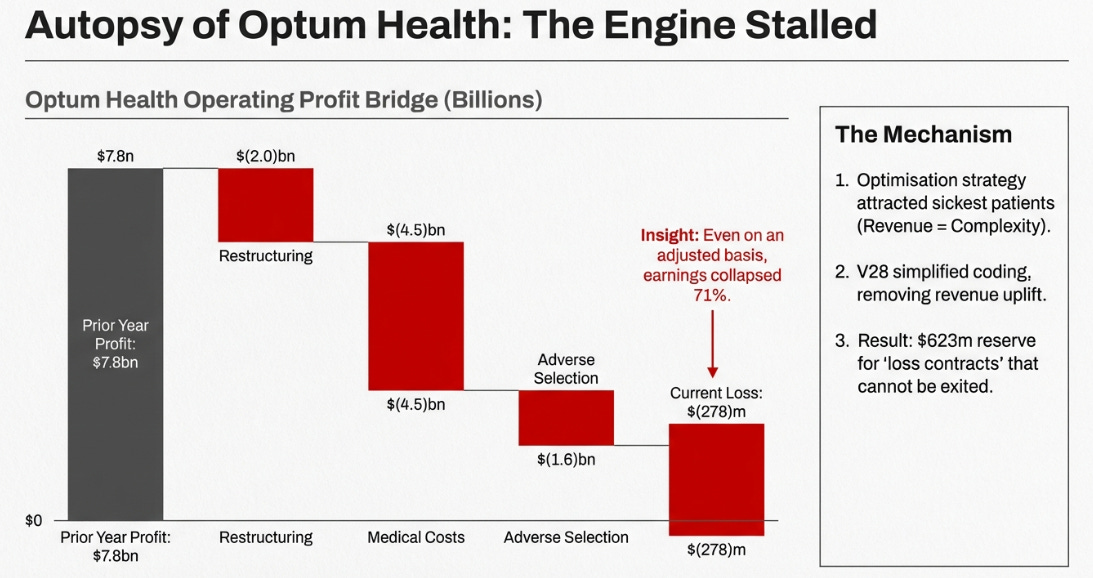

Optum Health reported an operating loss of $278 million, compared to $7.8 billion in operating profit the prior year. Even on an adjusted basis, stripping out restructuring charges, operating earnings collapsed 71% to $2.3 billion. The segment that was supposed to be the engine of UnitedHealth’s future generated margins of negative 0.3%.

The company also disclosed a $623 million reserve for “loss contracts”, agreements that management described as “structurally unprofitable” and that they “could not exit for 2026.” This is adverse selection made explicit. The optimization strategy attracted the sickest patients because complexity generated revenue. Under V28’s simplified coding rules, those patients still require expensive care, but the revenue uplift is gone.

And then there was the headline that mattered more than any earnings-per-share figure: UnitedHealth guided revenue to decline in 2026. This will be the first annual revenue contraction since 1989, thirty-six years of uninterrupted growth, ended.

The Numbers in Context

Before diving into what management said, it’s worth grounding the discussion in the specific figures that tell this story:

UnitedHealthcare (Insurance):

Operating earnings: $9.4 billion vs $15.6 billion prior year (-40%)

Operating margin: 2.7% vs 5.2% prior year

Medicare Advantage members to be shed in 2026: 1.3-1.4 million

Total membership contraction guided: 2.3-2.8 million

Optum Health (Care Delivery):

Operating earnings: $(278) million vs $7.8 billion prior year

Adjusted operating earnings: $2.3 billion vs $7.9 billion prior year (-71%)

Locations being closed or sold: 550 (approximately 20% of footprint)

Risk membership streamlined: 15%

Affiliated network narrowed: 20%

Optum Rx (Pharmacy Benefits):

Operating earnings: $7.2 billion vs $5.8 billion prior year (+24%)

The only segment showing growth and margin expansion

Medical Care Ratio:

2024: 85.5%

2025: 88.9% (adjusted)

2026 guidance: 88.8% ± 50 bps

The pattern is clear. The business built on coding optimization (Optum Health) has collapsed. The insurance business (UnitedHealthcare) is contracting deliberately to restore margins. The only segment performing well (Optum Rx) is the one whose economics don’t depend on Medicare billing rules.

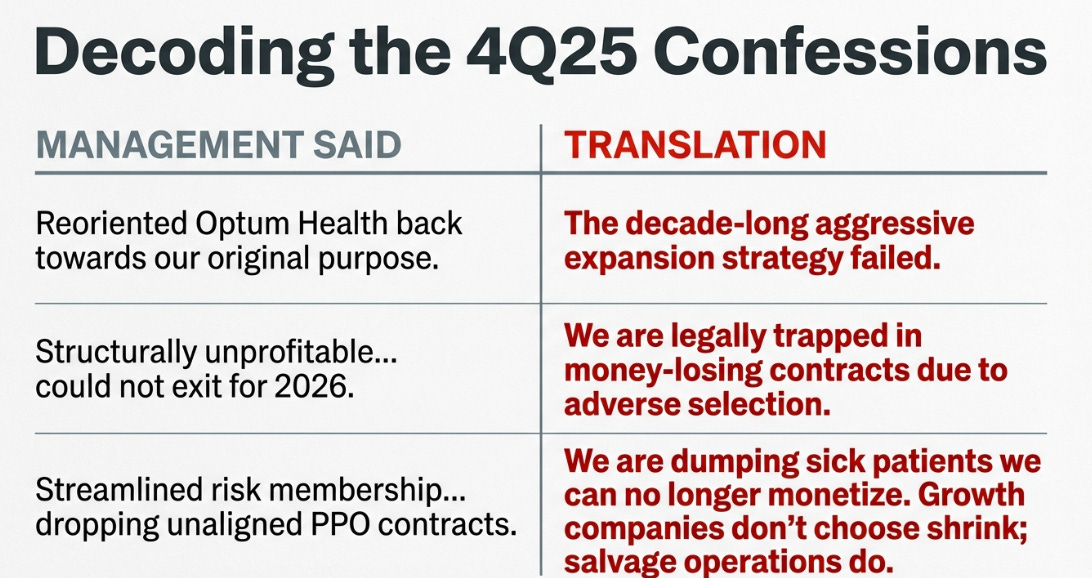

What Management Actually Said

Earnings calls are often exercises in obfuscation. This one was different. The transcript reads like a series of confessions, each more revealing than the last.

On the intentional shrink:

“Our 2026 approach favored margin recovery, and these membership trends are a result of these actions... these are greater losses than originally anticipated, as competitive market dynamics drove higher than expected plan shopping during the intensely competitive annual enrollment period.” , Tim Noel, CEO, UnitedHealthcare

This is important. UnitedHealth isn’t losing members to competitors because of poor service or unattractive benefits. It is deliberately shedding members it can no longer profitably serve under the new reimbursement rules. Growth companies don’t choose shrink. Salvage operations do.

On the structurally unprofitable contracts:

“Approximately $625 million of this charge relates to a loss contract reserve for third party contractual relationships within the Optum portfolio that are structurally unprofitable, and that we could not exit for 2026.” , Wayne DeVeydt, CFO

Read that sentence carefully. “Structurally unprofitable” means the losses aren’t from execution problems that better management can fix. They’re baked into the contract terms. “Could not exit” means UnitedHealth is trapped, legally obligated to continue losing money on these arrangements through at least 2026. This is the adverse selection problem I identified in my 3Q piece, now quantified and reserved against.

On the Optum Health restructuring:

“We have reoriented Optum Health back towards our original purpose... we’ve narrowed our affiliated network by nearly 20% since this time last year... we have streamlined our risk membership by approximately 15%. This reflects dropping unaligned PPO contracts, repositioning certain markets.” , Krista Postai, CEO, Optum Health

When a company says it’s returning to “original purpose” after a decade of aggressive expansion, it’s admitting that expansion failed. The language throughout, “reoriented,” “streamlined,” “narrowed,” “dropping”, is the vocabulary of retreat, not optimization.

On the path to margin recovery:

“We do have many high performing markets today that really deliver strong outcomes for our patients. One example worth highlighting is a large market in Texas, where we serve over 750,000 patients across over 50 clinics... we’ve got total cost of care that is approximately 30% better than our competitors.” , Krista Postai, CEO, Optum Health

This is the bull case, that pockets of genuine value-based care excellence exist within Optum Health and can be scaled. But notice what it implies: after a decade of integration and tens of billions in investment, management is pointing to one market in Texas as evidence the model works. The question investors must ask is why, if the integrated care model genuinely produces 30% cost advantages, those results aren’t evident in the segment’s overall financials.

On 2027 Medicare rates:

“The news that we received last night in the advance notice was disappointing. And it was because it’s a further reduction for a program that has experienced $130 billion in benefit or funding reductions over the last three years under the prior administration... it will mean very meaningful benefit reductions and will once again need to take a hard look at our geographic footprint.” , Tim Noel, CEO, UnitedHealthcare

The advance notice proposed a 0.09% increase in Medicare Advantage payment rates for 2027. Wall Street had expected 4-6%. This single data point killed the political rescue thesis that many bulls had been counting on.

The Mean Reversion Trap

In August 2025, Berkshire Hathaway disclosed a position of over 5 million shares in UnitedHealth, accumulated during the second quarter when the stock traded between $250 and $350. The logic was vintage Buffett: a great compounder had stumbled, the drawdown was driven by temporary factors, and patient capital would be rewarded when the business reverted to its historical performance.

The disclosure created what I’d call a psychological put. Berkshire’s imprimatur suggested the bottom was in. The stock rallied. Other value investors followed. The mean reversion trade was on.

Six months later, the stock trades at $282, and that Berkshire position is underwater. The question worth examining is why the mean reversion playbook failed.

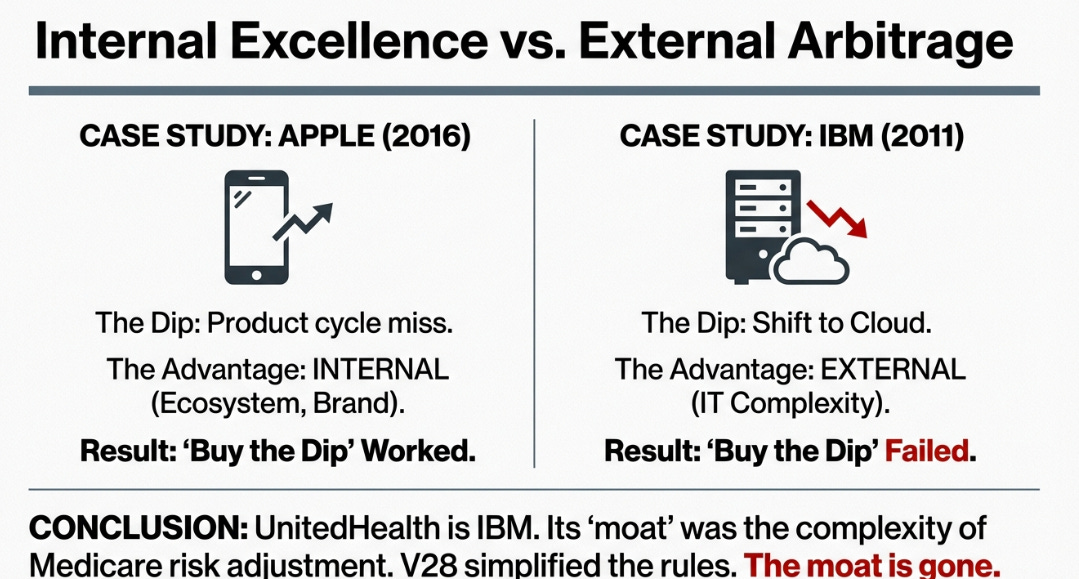

Mean reversion is a powerful strategy when applied to the right situations. It works when a fundamentally strong business experiences temporary disruption, a product cycle miss, a one-time expense, a demand shock that reverses. The key word is temporary. The strategy assumes the “mean” to which prices revert represents the company’s normal, sustainable economics.

But what if the mean itself has moved?

Consider the difference between Apple in 2016 and IBM in 2011. Both were dominant technology companies that experienced significant stock declines. Both attracted value investors who saw opportunity in the drawdown.

Apple’s advantages were internally generated: ecosystem lock-in, brand loyalty, pricing power rooted in consumer demand. When iPhone sales disappointed, the solution was a better iPhone. The mean, Apple’s ability to generate premium margins through superior products, was intact. Buying the dip worked spectacularly.

IBM’s advantages were externally generated: enterprise switching costs, long-term service contracts, relationships built on navigating IT complexity. When cloud computing emerged, those advantages didn’t transfer to the new paradigm. IBM’s mean, its ability to generate premium margins through integrated complexity, had been structurally impaired. Buffett held for six years before selling at a loss and publicly acknowledging his mistake.

UnitedHealth’s situation maps more closely to IBM than Apple. The company’s extraordinary historical margins weren’t solely the product of operational excellence. They were partly the product of regulatory complexity, specifically, a Medicare risk adjustment system that rewarded sophisticated documentation. V28 simplified that system. The regulatory mean has moved, and UnitedHealth’s financial mean is moving with it.

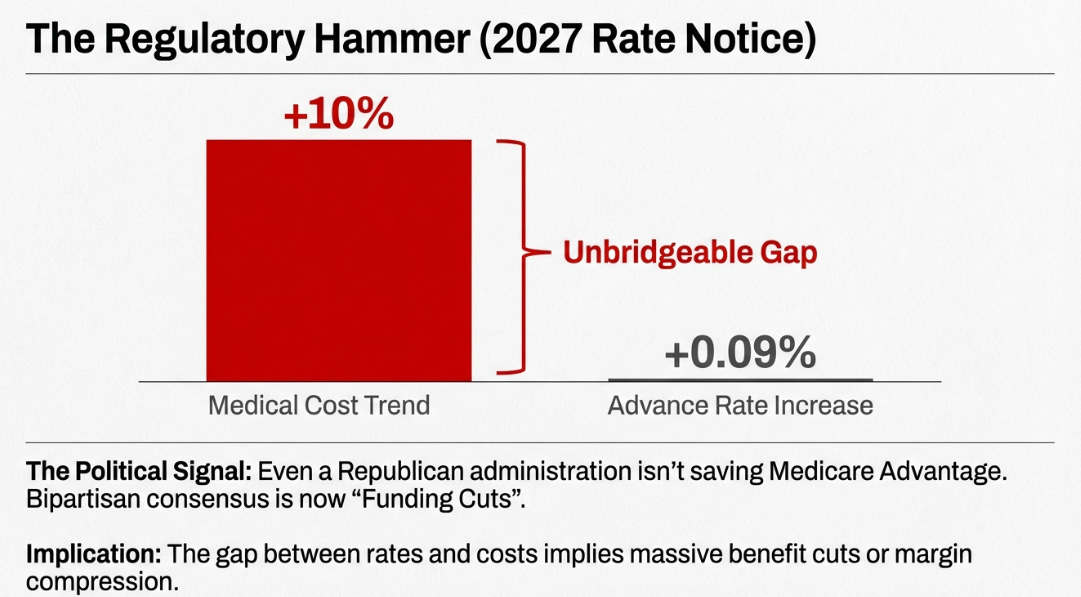

The 2027 Rate Notice

The bulls had one remaining hope: that the Trump administration would reverse course on Medicare Advantage funding. Industry-friendly regulators, the thinking went, would recognize that years of rate cuts were threatening seniors’ benefits and access to care.

The 0.09% advance notice ended that hope.

To understand why this matters, consider the math. UnitedHealth is projecting 2026 medical cost trend of 10% in Medicare. A 0.09% rate increase doesn’t come close to covering that, it doesn’t even cover inflation. Every percentage point of gap between rate increases and cost trend flows directly to margin compression or benefit cuts.

More importantly, the political signal is devastating. If a Republican administration, presumably the most industry-friendly configuration possible, won’t meaningfully increase Medicare Advantage rates, no one will. This isn’t partisan. It’s bipartisan consensus that the era of generous MA funding is over.

Tim Noel’s response on the call was notably subdued: “We’re going to, of course, work with CMS from now until the rates are finalized.” But the advance notice is typically close to the final rule. Management is preparing for another year of benefit reductions and market exits, not relief.

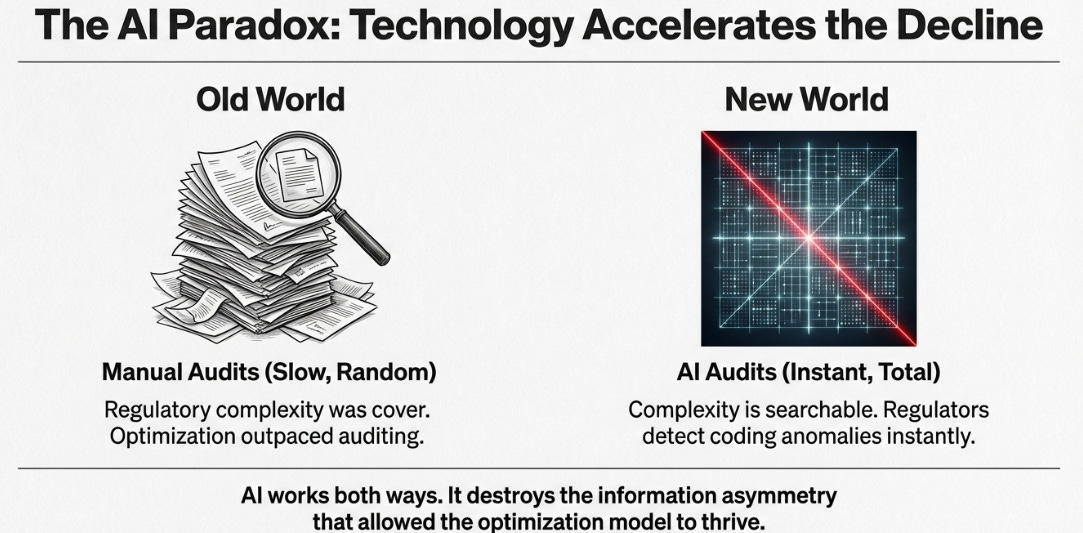

The AI Paradox

Management offered investors a new source of hope on the call: artificial intelligence. The company plans to invest nearly $1.5 billion in AI in 2026, expects significant operating cost reductions, and highlighted that over 80% of member calls now leverage AI tools.

This narrative isn’t wrong, exactly. AI will make UnitedHealth more efficient. But it ignores a symmetry that should concern anyone betting on a return to the old model.

The same artificial intelligence that optimizes UnitedHealth’s operations can optimize regulatory scrutiny. Pattern detection algorithms that identify billing inefficiencies can identify billing anomalies. Machine learning that predicts patient needs can flag provider outliers. The asymmetry that defined the old game, UnitedHealth could optimize faster than CMS could audit, is eroding.

In the old world, regulatory complexity was cover. Audits were manual, slow, and sampled tiny fractions of claims. Optimization strategies could operate in the gaps between enforcement actions.

In the AI world, complexity is searchable. Every claim can be analyzed algorithmically. Every coding pattern can be compared against statistical benchmarks. Every optimization strategy leaves a signature that machine learning can detect.

UnitedHealth isn’t wrong to invest in AI. But the investment won’t restore the old model. If anything, it accelerates the transition to a world where the returns to regulatory arbitrage approach zero.

Variant Perception

Despite everything I’ve described, the Bloomberg consensus still shows 2028 earnings per share of approximately $24, implying 15%+ annual growth from 2026 levels. Analysts are modeling Optum Health margins recovering to 5-6%. Revenue growth is expected to resume at mid-single digits.

This is the old mean, applied to a company that no longer operates under the old rules.

My variant perception is simpler. UnitedHealth will stabilize. It will likely return to modest growth eventually. But the destination is not the premium compounder of 2010-2023. The destination is a utility: lower margins, lower growth, a lower multiple, and permanently elevated regulatory scrutiny.

The market prices UnitedHealth at roughly 16 times forward earnings, which looks cheap against historical averages. But that “E” assumes a recovery trajectory the evidence doesn’t support. If the earnings power is structurally lower, the multiple should be too.

Updated Scenarios

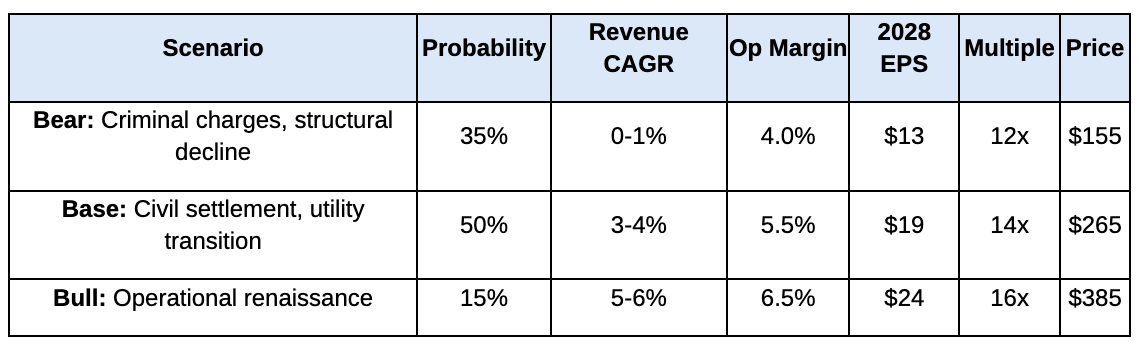

My framework from the 3Q piece remains intact, but the probabilities have shifted given the 2027 rate notice and the depth of Optum Health’s problems.

The distribution is asymmetric. The bear and base cases, which together represent 85% probability, both imply prices below today’s level. The bull case requires proof that value-based care works without coding optimization, proof that a decade of integration has failed to produce at scale.

What to Watch

Several data points over the coming months will clarify which scenario is materializing:

February 2026: Berkshire Hathaway’s 13F filing covering Q4 2025. Did Buffett hold, add, or begin exiting? A reduction would remove a psychological support that has buoyed the stock.

April 2026: Final 2027 Medicare Advantage rates. Any meaningful improvement from the 0.09% advance notice would be bullish; finalization at or below that level confirms the hostile funding environment.

H1 2026: DOJ resolution. Criminal charges push firmly into bear territory. Civil settlement in the $8-12 billion range enables base case stabilization.

Quarterly: Optum Health margins. Sequential improvement toward 2.5% would support the base case. Continued volatility below 2% suggests the structural problems remain unresolved.

Quarterly: Medical care ratio. Improvement toward 87.5% suggests repricing is working. Persistence above 89% indicates cost trends remain uncontrolled.

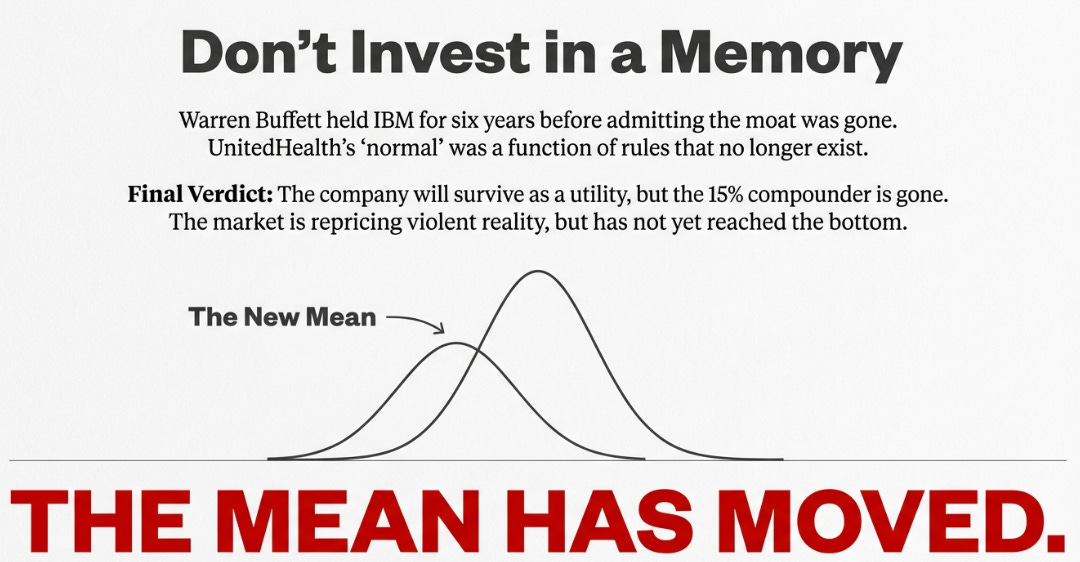

Conclusion

Warren Buffett held IBM for six years before acknowledging his mistake. The competitive dynamics had changed, he said. The moat he thought he saw, built on enterprise switching costs and long-term relationships, hadn’t transferred to the cloud computing era.

Watching UnitedHealth’s 4Q25 results, I found myself wondering whether history is rhyming. The mean reversion buyers saw a great company having a bad year. They saw a 50% drawdown and applied the playbook that usually works: buy quality when it’s cheap, wait for the business to normalize, collect the gains.

But UnitedHealth’s “normal” was partly a function of rules that no longer exist. The V28 coding changes, the 2027 rate notice, the AI-enabled scrutiny environment, these aren’t temporary headwinds. They’re structural changes to the game itself.

The company will survive. Optum Rx will continue generating cash. The insurance business will stabilize at lower margins. Something will emerge from this restructuring. But that something won’t be the 15% compounder that Buffett thought he was buying, or that three decades of investors came to expect.

The mean has moved. The market spent last week violently repricing to that reality. Whether it has repriced enough remains the open question, one that the evidence suggests it has not.

Disclaimer:

The content does not constitute any kind of investment or financial advice. Kindly reach out to your advisor for any investment-related advice. Please refer to the tab “Legal | Disclaimer” to read the complete disclaimer.