Netflix Q3 2025: Winning the TV Battle, Losing the Streaming War

How a tax hit in Brazil, a maturing ad business, and revealing view-share charts tell two stories about Netflix’s future.

TL;DR:

Two Interpretations, One Reality: Netflix grew its TV view share but lost streaming share to YouTube, Roku, and free ad-supported platforms — both can be true, but only one drives the next decade.

Ads Are Walking, Not Running: The ad business is scaling but still opaque — “doubling revenue” sounds better than disclosing that ads may only be ~6–7% of total revenue.

Margins Meet Reality: The Brazil tax charge exposed deeper structural headwinds — global regulation, rising sports costs, and ad tech investment may cap operating margins near 30%.

Wall Street was not impressed; from Bloomberg:

Netflix Inc. shares fell the most since April 2022 after a tax dispute with Brazil cut into third-quarter earnings and raised growth concerns among investors used to positive surprises from the streaming leader. Operating income was $3.24 billion in the period, according to a statement Tuesday, about $400 million below the company’s forecast and analysts’ estimates. For the first time in more than two years, revenue failed to beat Wall Street estimates, according to data compiled by Bloomberg...

Netflix shares fell as much as 10% to $1,117.00 on Wednesday, the biggest intraday drop in more than three years. The stock hit an all-time high of $1,341.15 on June 30, the final day of the previous quarter, and has drifted lower over the last few months.

What caught my attention wasn’t the Brazil charge — that’s the kind of one-time event that can be stripped out in analysis — but rather a specific set of charts in Netflix’s shareholder letter.

The text reads:

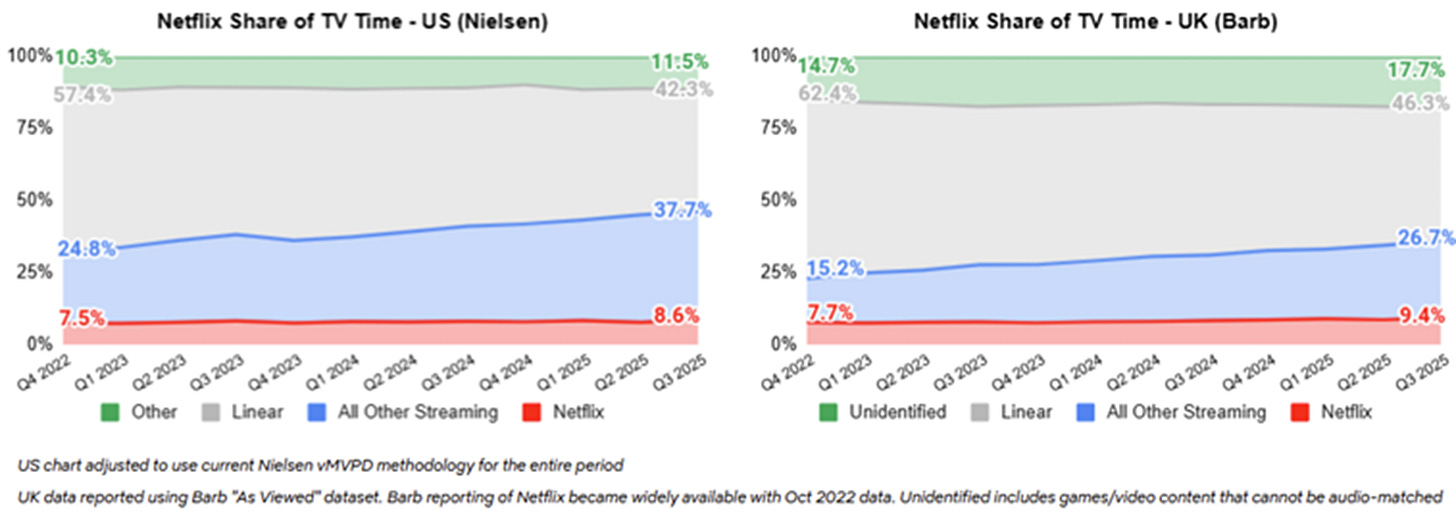

Our successful slate helped us drive record TV view share in Q3 in the United States and the United Kingdom, two of our largest markets. Based on Nielsen and Barb data, from Q4’22-Q3’25, our quarterly TV view share has grown 15% and 22% in the US and UK, respectively, as you see in the charts below. Given the still substantial amount of linear viewing globally, we believe there’s plenty of opportunity to expand our share of TV engagement, if we continue to improve.

When I saw those charts, I immediately noticed what they weren’t showing. Yes, Netflix’s view share has grown 15% and 22% in the US and UK respectively since Q4 2022. But look at what happened to total streaming share over the same period: streaming as a whole grew from 24.8% to 37.7% in the US (a 52% increase) and from 15.2% to 26.7% in the UK (a 76% increase).

In other words, Netflix is capturing some portion of the shift from linear to streaming, but not even close to a majority of that shift. Both interpretations are valid — Netflix is gaining TV share and losing streaming share — but which one matters depends entirely on what you believe about the future.

To be clear, Netflix’s interpretation isn’t wrong: there is still “plenty of opportunity to expand share of TV engagement” as linear continues to decline. What I think happened here is that Netflix got fixated on its own interpretation of these graphs and didn’t anticipate how investor sentiment, particularly in a quarter where the company missed expectations, might lead to a different reading. The other way to interpret those same graphs is that YouTube, Roku, Tubi, and other free ad-supported services — along with competitors’ streaming offerings — are capturing the majority of streaming’s growth, and have been for several years now.

The Ad Business That Won’t Show Its Hand

What is encouraging, however, is that for the third quarter running, advertising was given explicit credit for revenue growth. Co-CEO Greg Peters said on the earnings call:

Consistent with the last comment and answer, we made considerable progress in building out our general capabilities in the ad space. So if you use our beloved crawl-walk-run model, we’re now squarely in that walking phase. The rollout of the ads suite, our own ad suite has been great because it means we’re just continuing to learn and improve the stack based on client feedback. So we’ve got really fast iteration loop going there that we’re excited about. Key priorities and focus for us is making it easier for advertisers to buy on our service. We want to increase the diversity of advertisers we have. That’s a key direction of growth for us that enables that revenue growth. We’re adding more demand sources like Amazon DSP, AJA in Japan. We’re improving our own ad sales and go-to-market capabilities.

This is interesting framing: crawling was building the ad product, walking is generating demand, and running — which is still ahead — is “ML-based optimization, advanced measurement, advanced targeting.” That’s a long runway, which is itself a reason for optimism. It also means Netflix is much earlier in the ad monetization journey than the “best ad sales quarter ever” headline might suggest.

What Netflix still won’t disclose, however, is absolute ad revenue figures. After three years in the business, the continued opacity is notable. Peters said they’re “on track to more than double ad revenue in 2025,” but doubling from what base? My estimate, based on various industry sources and the company’s total revenue trajectory, is that Netflix is running at a $2-3 billion annual ad revenue rate, which would make it about 6-7% of total revenue. That’s material progress, but it’s not yet the transformative business some bulls have modeled.

The other thing Netflix wouldn’t disclose: hours watched per subscriber. They highlighted view share gains, but view share is a relative metric. What I wanted to know — and what I suspect investors wanted to know after Bloomberg mentioned “concerns that Netflix customers aren’t increasing the amount of time they spend on the service” — was whether absolute engagement per member is growing, flat, or declining. The silence on this metric was conspicuous.

KPop Demon Hunters and the Hit Discovery System

There was one piece of management commentary that I found fascinating. Co-CEO Ted Sarandos, discussing KPop Demon Hunters’ success, said:

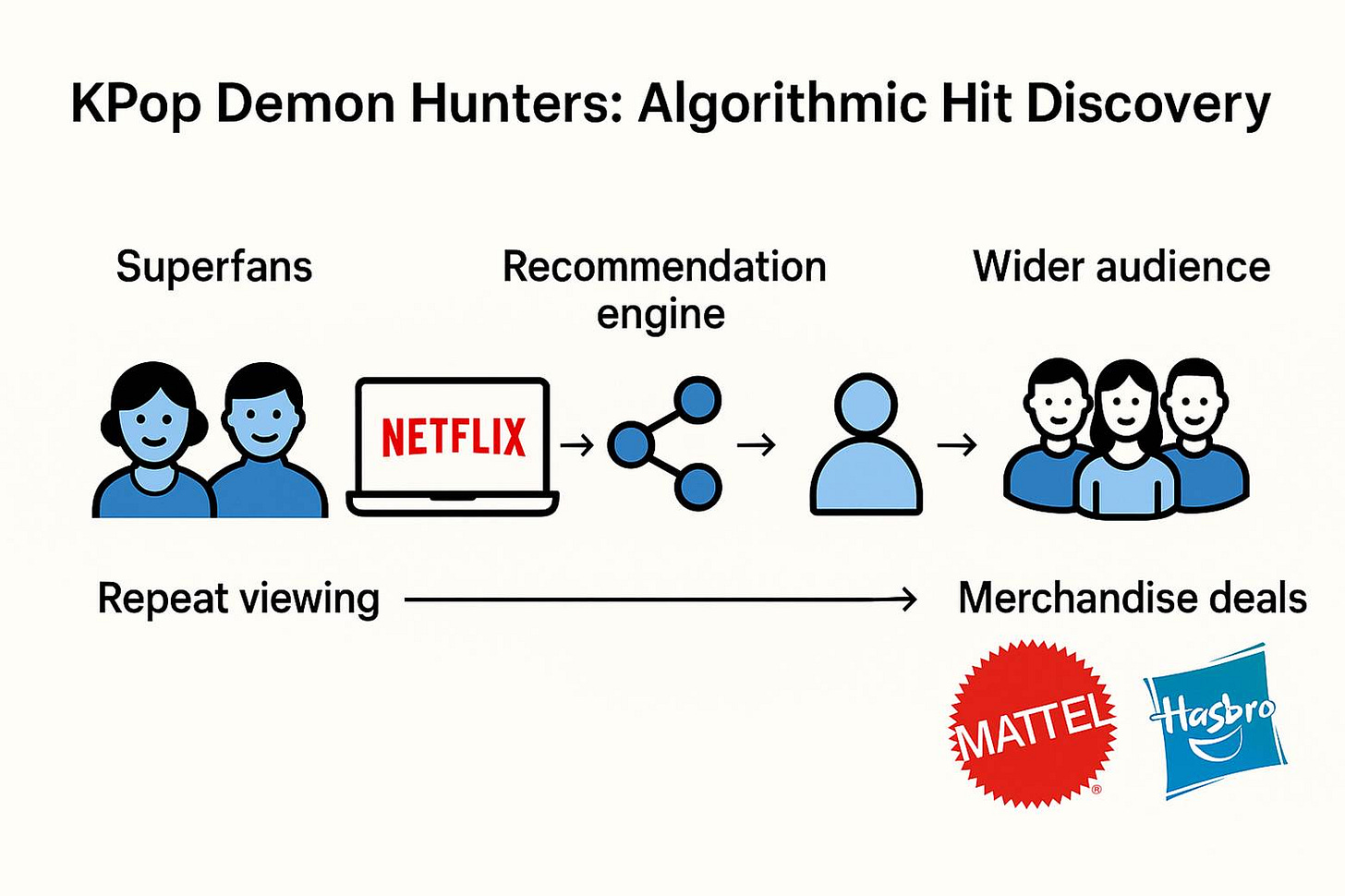

We believe that this film, KPop Demon Hunters, actually worked because it was released on Netflix first. Look, we had a film that people fell in love with, that’s first and foremost. But not in a huge way on the first day or even the first weekend. In fact, it was the super fans who watched the movie and repeat watched the movie that drove the recommendation engine that got it in front of more super fans who also fell in love with the movie. So that ease and value that allowed folks to repeat view it.

This is a remarkably humble admission: Sarandos isn’t claiming that he or any human at Netflix knew KPop Demon Hunters would become their biggest film ever (325 million views). Rather, it was the structure of Netflix itself — the recommendation algorithm, powered by super fans’ repeat viewing — that discovered the film was a burgeoning hit and automatically capitalized on it.

This structural explanation — as opposed to a human auteur one — matters because it suggests Netflix has built a genuine hit-discovery system rather than relying purely on executive intuition. It’s also humbling in that even Netflix, with all its data and experience, couldn’t predict this level of success in advance.

The proof is in what happened next. From Bloomberg:

Mattel Inc. and Hasbro Inc. will produce toys, collectibles, games and role-play products based on Netflix Inc.’s popular KPop Demon Hunters film. The first products from the collaboration will be released in 2026, Netflix said in a statement Tuesday.

Two things are remarkable here. First, Netflix signed up both of the biggest toy makers, not just one — that’s the scale of the hit. Second, toys won’t arrive until 2026, which means they’ll miss Christmas 2025 entirely. KPop Demon Hunters was released in June; if Netflix had known it would become this big, they would have fast-tracked merchandise for the holiday season. The fact that they didn’t suggests the success truly was unexpected and slow-building.

This raises an interesting strategic question: does Netflix’s streaming-native discovery system — where hits build over time through algorithmic amplification — fundamentally conflict with traditional franchise economics, which depend on advance planning for merchandise, theme parks, and licensing? Or is this just a learning curve that Netflix will master over time?

Disney has had a century to build franchise IP with predictable merchandising cycles. Netflix is attempting to build that capability from scratch, in a streaming-native way where hits are discovered rather than planned. Stranger Things and Squid Game suggest it can be done, but the question remains whether streaming series create the kind of enduring, multi-generational franchises that theatrical releases have historically produced.

The Brazil Charge and International Economics

Now, about that Brazil tax dispute. CFO Spence Neumann explained on the call:

It’s not a tax that’s specific to Netflix. It’s not even specific to streaming. Absent this expense, we would have exceeded our Q325 operating income and operating margin forecast, and we don’t expect this matter to have a material impact on our results going forward.

The $619 million charge covers periods from 2022 through Q3 2025 — roughly three and a half years. This wasn’t a surprise in the sense that Netflix had disclosed it as a “potential exposure” in previous 10-Q and 10-K filings. What changed was that it became “reasonably likely” that Netflix would lose the legal challenge, triggering the accounting requirement to book the expense.

What’s interesting about this — beyond the immediate margin impact — is what it reveals about the economics of international expansion. Netflix operates in more than 190 countries, many with complex and evolving tax regimes. Brazil’s 10% tax on certain outbound payments isn’t Netflix-specific; it applies broadly to companies making payments from Brazilian entities to foreign operations.

The question this raises: if Netflix faces similar regulatory friction in India, Indonesia, Turkey, Argentina, and other major growth markets, does international expansion carry a structural 1-2% margin drag that wasn’t fully appreciated? Or is Brazil truly an outlier?

I don’t have the answer, but I think it’s the right question to be asking. Netflix has been early and aggressive in international expansion, which has been a huge competitive advantage. But being early sometimes means navigating regulatory frameworks that weren’t designed for your business model. The cost of that navigation may be higher than initially modeled.

To put the margin miss in context: absent the Brazil charge, Netflix would have posted approximately 33% operating margin, exceeding their 31.5% guidance. The question is whether “absent Brazil” is the right way to think about it, or whether international regulatory friction should be considered part of the normal course of business going forward.

Live Sports and Content Breadth

One more area where Netflix made notable progress: live sports. The Canelo vs. Crawford boxing match attracted more than 41 million viewers, making it the most-viewed men’s championship boxing match this century. The event was #1 on Netflix in 30 countries and generated over 950 million social impressions.

More significantly, Netflix has NFL Christmas Day games coming in Q4 — a doubleheader featuring high-profile matchups that could drive both acquisition and retention. Co-CEO Greg Peters has been explicit about the strategic rationale:

If a user really only cares about watching Wednesday Season 2 and the NFL, then the NFL games Netflix will host this year should keep them around for longer.

This is content breadth as a churn reduction strategy. Netflix doesn’t have the multi-billion-per-year deals with professional sports leagues that traditional networks have. It doesn’t have news programming or daily late-night shows. By adding live sports selectively — boxing matches, WWE, now NFL Christmas games — Netflix is betting it can reduce cancellations during the gaps between major content releases.

The economic question is whether this is offense or defense. Does live sports drive new subscriptions at attractive customer acquisition costs? Or is it primarily an expensive way to prevent existing subscribers from churning?

We’ll learn a lot more in Q4. If the NFL Christmas games drive measurable retention improvement or a signup surge, that validates the content breadth strategy. If it’s just expensive table stakes that every streamer now needs, that’s a different story entirely — one that linear TV could tell you all about.

Connecting Back to Previous Analysis

When I wrote about [Netflix’s margin expansion thesis earlier this year], I argued that the company’s shift from growth-at-all-costs to profitable growth represented a fundamental business model evolution. The core question was whether Netflix could achieve 35%+ operating margins while continuing to invest heavily in content.

Q3 provides some answers, though not definitive ones. The Brazil charge muddles the picture — 28.2% reported margin versus what would have been ~33% absent the charge. The Q4 guidance of 23.9% operating margin is seasonally depressed (Q4 is always Netflix’s lowest margin quarter due to content release timing and holiday marketing spend). For the full year, Netflix now expects 29% operating margin, down from the prior 30% guidance.

What I think we’re learning is that operating leverage in streaming is real but faces more headwinds than the bull case appreciated:

International regulatory friction (Brazil may not be the last)

Live sports content costs (which escalate over time)

Ad tech investment with uncertain ROI

Currency volatility in high-growth markets

The question isn’t whether Netflix can reach 29-30% margins — they’re essentially there now. The question is whether 35%+ is achievable as the company scales, or whether 29-31% represents the realistic equilibrium for a global streaming business with Netflix’s content investment levels and geographic breadth.

I don’t know the answer yet. But I do think the Brazil charge, regardless of whether it’s truly one-time, has reset expectations about the margin expansion trajectory. The path to 35%+ now looks longer and less certain than it did three months ago.

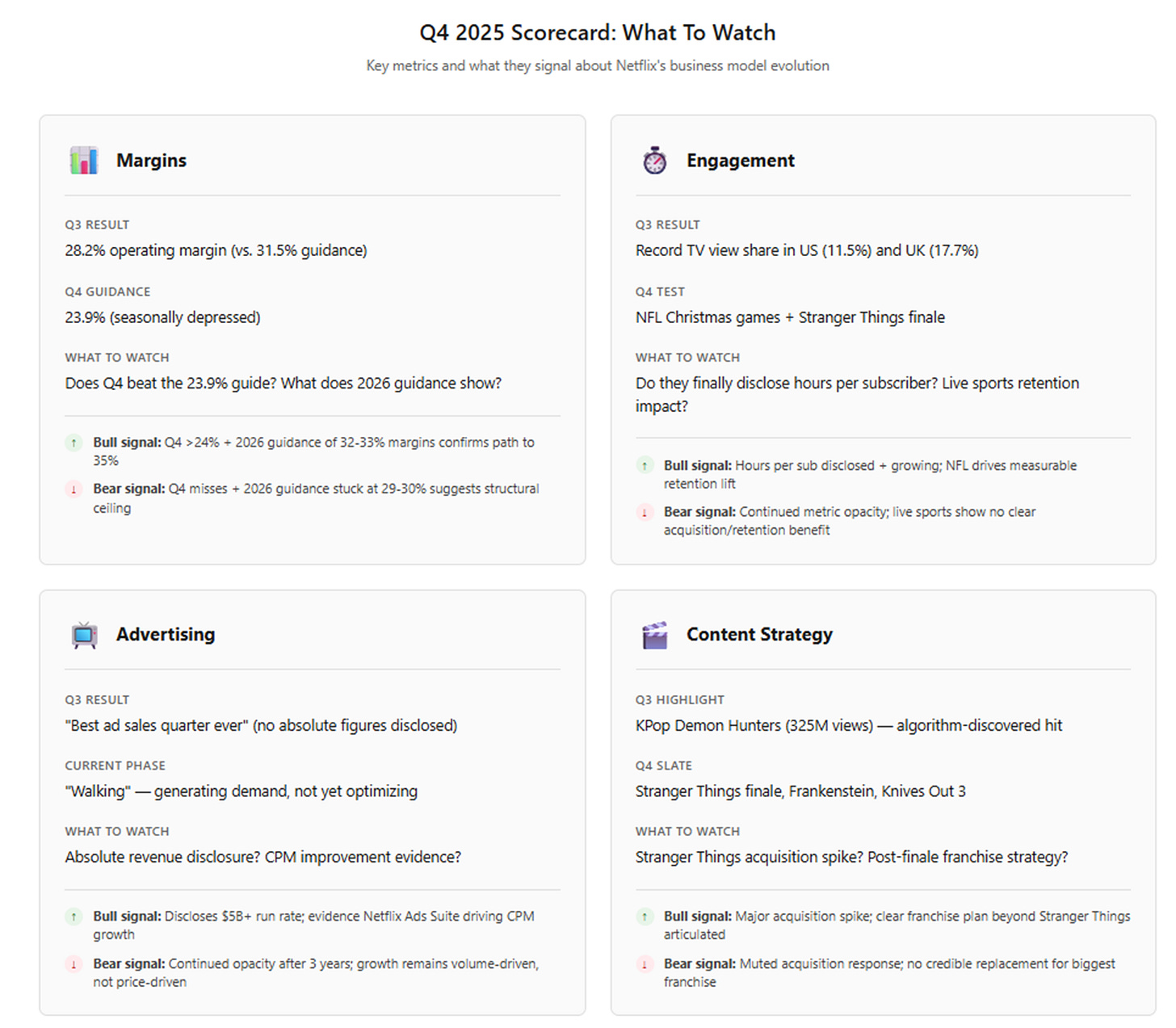

The Questions Q4 Must Answer

Netflix is finishing the year with what should be its strongest content slate: the final season of Stranger Things, new seasons of The Diplomat and Nobody Wants This, Guillermo del Toro’s Frankenstein, and those NFL Christmas Day games I mentioned.

Here’s what I’ll be watching for in Q4 results:

· On margins: Does Q4 beat the 23.9% operating margin guidance? More importantly, what does 2026 guidance look like — a path back toward 32-33% margins, or a signal that 29-30% is the new steady state?

· On engagement: Do the NFL games drive measurable retention improvement? Does management finally disclose hours per subscriber, or do they stick with view share metrics?

· On advertising: Three years into the ad business, does Netflix disclose absolute revenue figures? Is there evidence that the Netflix Ads Suite is driving CPM improvements, or is growth still primarily volume-driven?

· On content strategy: Does the Stranger Things finale drive a meaningful acquisition spike? And what’s the franchise strategy post-Stranger Things? KPop Demon Hunters is a hit, but can Netflix systematically build the kind of multi-generational franchises that Disney has?

The strategic question underlying all of this is whether streaming platform economics can support the 35%+ operating margins that bulls have modeled, or whether international complexity, content costs, and competitive dynamics create a natural ceiling in the 29-31% range. Netflix is still the clear leader in streaming, but leadership in a maturing industry looks different than leadership in a growth industry — the economics change, even if the market position doesn’t.

We’ll find out more in January when Q4 results are released. Until then, those view share charts remain instructive: Netflix is winning in TV, but the game is increasingly being played in streaming, and that’s where the competition is most intense.

Disclaimer:

The content does not constitute any kind of investment or financial advice. Kindly reach out to your advisor for any investment-related advice. Please refer to the tab “Legal | Disclaimer” to read the complete disclaimer.